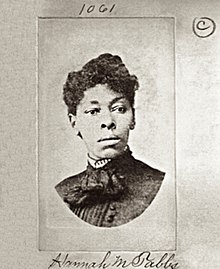

Hannah Mary Tabbs

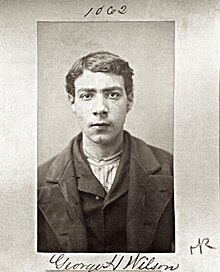

Hannah Mary Tabbs, born Hannah Ann Smith, was an American murderer in the late 1800s. Born into slavery in the 1850s, she escaped northward and settled in Philadelphia, where she and accomplice, George Wilson, were accused of murder after the discovery of a headless, limbless, mutilated torso. Prior to the discovery of the torso, Tabbs was known for violent acts against her black community but she had no criminal record until Tabbs and Wilson were accused of murder. Due to her consistent use of aliases and false information, little information is known about her life.[1]

Biography

[edit]Tabbs was born in Maryland in the 1850s. Ten years after the Civil War she moved north to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In Maryland, she lived with her husband, and niece Annie Richardson, though it is speculated[by whom?] she was Tabbs' daughter.

Crime

[edit]Tabbs had a reputation for violence and fraud among black people. She assaulted people and throughout her life used aliases and false identities. She often threatened family members, including her husband.[citation needed]

Tabbs became involved in an adulterous affair with 24 year-old Wakefield Gains, a mixed-race Philadelphia man. Tabbs threatened to kill Gains after she found him talking to a neighborhood girl. Two weeks later, Jennie Cannon, Gains' sister, reported him missing.[2][3]

Gains' mutilated torso was discovered in Colonel William B. Mann's ice pond, on February 17, 1887, in Eddington, PA by Silas Hibbs.[4] Philadelphia Police investigators Frank Geyer, James Tate, Thomas Crawford, and Peter Miller determined Tabbs, in conjunction with 18-year-old George Wilson, murdered Wakefield Gains.[5][6][7][8][9]

While in custody, Tabbs confessed that on the morning of February 16, 1887, George Wilson came to her home at 1642 Richards Street, Philadelphia. Wakefield Gains was already at her home that morning, casually reading the newspaper. Wilson and Gains got into an argument and Gains jumped out of his chair and struck Wilson. The two fought and Wilson hit Gains over the head with a chair. Gains fell to the ground and Wilson struck him several more times with the chair, then dragged Gains' body into her cellar. Tabbs said that Wilson removed Gains' clothes and after retrieving a butcher’s cleaver, he dismembered Gains. Tabbs said she took Gain's clothing and his torso, then boarded a 6:30 train and went to Eddington, where she "threw the body over in the water." Wilson also confessed to the crime, but stated that it was Hannah Mary Tabbs that dismembered Gains. He admitted he threw Gains' head and limbs in the Schuylkill River. Philadelphia Police Department investigators Frank Geyer, Thomas Crawford, Tate, and Miller, accompanied by George Wilson searched the river but never recovered the dismembered body parts.[10][11][12]

Philadelphia District Attorney George S. Graham prosecuted the case against Hannah Mary Tabbs and George Wilson. Coroner's Physician Dr. Henry F. Formad shocked the packed courtroom when he testified that Wakefield Gains was alive when dismembered.[13][14]

Tabbs was convicted of being an accessory to murder. Judge Hare sentenced her to two years in prison. Wilson was convicted of murder and sentenced to 12 years in Eastern State Penitentiary.[15][16]

Dramatization

[edit]The Hannah Mary Tabbs case was partly dramatized on an episode of the 2022 BBC Radio podcast series Lucy Worsley's Lady Killers.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Hannah Mary Tabbs: A black murderess in racist 1800s US - BBC News". BBC News. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta, CA: RW Publishing House. pp. 53–72. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- ^ "The Woman Found". Philadelphia Times. February 22, 1887. p. 1.

- ^ "Murder of the Most Foul". Philadelphia Inquirer. February 22, 1887. p. 1.

- ^ Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta CA: RW Publishing House. pp. 53–72. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- ^ "Murder Confessed". Philadelphia Times. February 23, 1887. p. 1.

- ^ "Ordinary Yet Infamous: Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso". notevenpast.org. February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ "Looking for the Woman". Philadelphia Times. February 21, 1887.

- ^ "Dragging the Pond". Philadelphia Times. February 19, 1887.

- ^ "The Mystery Solved". Philadelphia Inquirer. February 23, 1887.

- ^ Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta CA: RW Publishing House. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- ^ "A Partial Confession". Delaware Gazette and State Journal. March 3, 1887. p. 2.

- ^ "Dismembered While Living". New York Herald. June 2, 1887.

- ^ Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta CA: RW Publishing House. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- ^ Gross, Kali Nicole (2016). Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta CA: RW Publishing House. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley".