Heat shock protein 90kDa alpha (cytosolic), member A1

Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HSP90AA1 gene.[5][6]

Function

[edit]The gene, HSP90AA1, encodes the human stress-inducible 90-kDa heat shock protein alpha (Hsp90A). Complemented by the constitutively expressed paralog Hsp90B which shares over 85% amino acid sequence identity, Hsp90A expression is initiated when a cell experiences proteotoxic stress. Once expressed Hsp90A dimers operate as molecular chaperones that bind and fold other proteins into their functional 3-dimensional structures. This molecular chaperoning ability of Hsp90A is driven by a cycle of structural rearrangements fueled by ATP hydrolysis. Current research on Hsp90A focuses in its role as a drug target due to its interaction with a large number of tumor promoting proteins and its role in cellular stress adaptation.

Gene structure

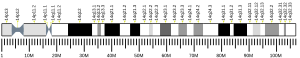

[edit]Human HSP90AA1 is encoded on the complement strand of Chromosome 14q32.33 and spans over 59 kbp. Several pseudogenes of HSP90AA1 exist throughout the human genome located on Chromosomes 3, 4, 11 and 14.[7] The HSP90AA1 gene encodes for two distinct mRNA transcripts initiated from separate transcription start sites (TSS). No mRNA splice variants of HSP90AA1 have presently been verified. Transcript variant 1 (TV1, NM_001017963.2) encodes the infrequently observed 854 amino acid isoform 1 of Hsp90A (NP_001017963) from a 3,887 bp mRNA transcript containing 12 exons spanning 59, 012 bp. Transcript variant 1 is located directly next to the WDR20 gene, which is encoded on the opposite coding strand. Transcript variant 2 (TV2, NM_005348.3) encodes the well-studied 732 amino acid isoform 2 (NP_005339) from a 3,366 bp mRNA transcript containing 11 exons spanning 6,438 bp. DYNC1H1 encodes the gene product on the other side of HSP90AA1, which coincidentally has been found to interact with Hsp90A. Hsp90A TV1 and TV2 are identical except for an additional 112 amino acids on the N-terminus of isoform 1 encoded by its first 2 exons. The function of the extended N-terminal domain on isoform 1 is currently not understood. This information was gathered from both NCBI Gene and the UCSC Genome Browser.

Expression

[edit]Despite sharing similar amino acid sequence, Hsp90A expression is regulated in a different manner than Hsp90B. Hsp90A is the stress inducible isoform while Hsp90B is expressed constitutively. Several heat shock elements (HSE) are located upstream of Hsp90A allowing for its inducible expression. RNA levels measured in cell lines collected from cancer patients as well as normal tissue can be found at The Human Protein Atlas.

Promoter

[edit]Transcription of the HSP90AA1 gene is currently understood to be induced by stress through binding of the master transcription factor (TF) HSF1 to the HSP90AA1 promoter.[8] However, several focused studies of the HSP90AA1 promoter along with extensive global analysis of the human genome indicate that various other transcription complexes regulate HSP90AA1 gene expression. Mammalian HSP90AA1 along with HSP90AB1 gene expression was first characterized in transformed mouse cells where it was shown that HSP90AB1 is constitutively expressed 2.5-fold higher than HSP90AA1 under normal conditions. However upon heat shock, HSP90AA1 expression increased 7.0-fold while HSP90AB1 increases only 4.5-fold.[9] Detailed analysis of the HSP90AA1 promoter shows that there are 2 heat shock elements (HSE) within 1200 bp of the transcription start site.[10][11] The distal HSE is required for heat shock induction and the proximal HSE functions as a permissive enhancer. This model is supported by ChIP-SEQ analysis of cells under normal conditions where HSF1 is found bound to the proximal HSE and not detected at the distal HSE. The proto-oncogene MYC is also found to induce HSP90AA1 gene expression and binds proximally to the TSS as verified by ChIP-SEQ. Depletion of Hsp90A expression indicates that HSP90AA1 is required for MYC-driven transformation.[12] In breast cancer cells the growth hormone prolactin induces HSP90AA1 expression through STAT5.[13] NF-κB or RELA also induces HSP90AA1 expression possibly explaining the pro-survival ability of NF-κB-driven transcription.[14] Conversely, STAT1, the proto-tumor suppressor, is found to inhibit stress induced expression of HSP90AA1.[15] In addition to these findings, ChIP-SEQ analysis of the human genome indicates that at least 85 unique TFs bind to the RNA polymerase II (POLR2A) footprints associated with the promoter regions that drive the expression of both HSP90AA1 transcript variants.[16][17][18][19] This indicates that HSP90AA1 gene expression may be highly regulated and complex.

Interactome

[edit]Combined, Hsp90A and Hsp90B are predicted to interact with 10% of the eukaryotic proteome.[20] In humans this represents a network of roughly 2,000 interacting proteins. Presently over 725 interactions have been experimentally documented for both HSP90A and Hsp90B.[21][22] This connectivity allows Hsp90 to function as a network hub linking diverse protein interaction networks. Within these networks Hsp90 primarily specializes in maintaining and regulating proteins involved in signal transduction or information processing. These include transcription factors that initiate gene expression, kinases that transmit information by post-translationally modifying other proteins and E3-ligases that target proteins for degradation via the proteosome. Indeed, a recent study utilizing the LUMIER method has shown that human Hsp90B interacts with 7% of all transcription factors, 60% of all kinases and 30% of all E3-ligases.[23] Other studies have shown that Hsp90 interacts with various structural proteins, ribosomal components and metabolic enzymes.[24][25] Hsp90 has also been found to interact with a large number of viral proteins including those from HIV and EBOLA.[26][27] This is not to mention the numerous co-chaperones that modulate and direct HSP90 activity.[28] Few studies have focused on discerning the unique protein interactions between Hsp90A and HSP90B.[29][30] Work done in Xenopus eggs and yeast has shown that Hsp90A and Hsp90B differ in co-chaperone and client interactions.[31][32] However, little is understood concerning the unique functions delegated to each human paralog. The Picard lab has aggregated all available Hsp90 interaction data into the Hsp90Int.DB website.[33] Gene ontology analysis of both Hsp90A and Hsp90B interactomes indicate that each paralogs is associated with unique biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components.

Heat shock protein 90kDa alpha (cytosolic), member A1 has been shown to interact with:

- AHSA1,[34]

- AKT1,[35][36][37]

- AR,[38][39]

- C-Raf,[40][41]

- CDC37,[42][43]

- DAP3,[44]

- EPRS,[45]

- ERN1,[46]

- ESR1[47][48]

- FKBP5,[49]

- GNA12,[50]

- GUCY1B3,[51]

- HER2/neu,[52][53]

- HSF1,[47][54]

- Hop,[55][56]

- NOS3,[51][57][58]

- NR3C1,[44][59][60][61][62][63][64]

- P53,[65][66][67]

- PIM1,[68]

- PPARA,[69]

- SMYD3,[70]

- STK11,[71]

- TGFBR1,[72]

- TGFBR2,[72] and

- TERT.[35][36]

Post-translational modifications

[edit]Post-translational modifications have a large impact on Hsp90 regulation. Phosphorylation, acetylation, S-nitrosylation, oxidation and ubiquitination are ways in which Hsp90 is modified in order to modulate its many functions. A summary of these sites can be found at PhosphoSitePlus.[73] Many of these sites are conserved between Hsp90A and Hsp90B. However, there are a few distinctions between the two that allow for specific functions to be performed by Hsp90A.

Phosphorylation of Hsp90 has been shown to have affect its binding to clients, co-chaperones and nucleotide.[74][75][76][77][78][79] Specific phosphorylation of Hsp90A residues have been shown to occur. These unique phosphorylation sites signal Hsp90A for functions such as secretion, allow it to locate to regions of DNA damage and interact with specific co-chaperones.[74][77][80][81] Hyperacetylation also occurs with Hsp90A which leading to its secretion and increased cancer invasiveness.[82]

Clinical significance

[edit]Expression of Hsp90A also correlates with disease prognosis. Increased levels of Hsp90A are found in leukemia, breast and pancreatic cancers as well as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[83][84][85][86][87] In human T-cells, HSP90AA1 expression is increased by the cytokines IL-2, IL-4 and IL-13.[88] HSP90, alongside other conserved chaperones and co-chaperones that interact to safeguard proteostasis, is repressed in aging human brains. This repression was found to be further exacerbated in the brains of patients with age-onset neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease.[89]

Cancer

[edit]Over the last two decades HSP90 has emerged as an intriguing target in the war on cancer. HSP90 interacts and supports numerous proteins that promote oncogenesis, thus distinguishing Hsp90 as a cancer enabler as it is regarded as essential for malignant transformation and progression. Moreover, through their extensive interactomes, both paralogs are associated with each hallmark of cancer.[90][91] The HSP90AA1 gene however is not altered in a majority of tumors according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Currently bladder cancer is found to have the largest number of alterations followed by pancreatic cancer.[92][93] This may not come as a surprise since overall Hsp90 expression levels are held at such a high level compared to most all other proteins within the cell,[94] therefore further increasing Hsp90 levels may not provide any benefit to cancer growth. Additionally, whole genome sequencing across all tumor types and cancer cell lines reveals that there are presently 115 different mutations within the HSP90AA1 open reading frame. The effects of these mutations on HSP90A function, however, remain unknown. Remarkably, in a number of tumors the HSP90AA1 gene is homozygously deleted, suggesting that these tumors may have a reduced level of malignancy. This is supported by a comparative genome-wide analysis of 206 gastric cancer patients that reported loss of HSP90AA1 is indeed associated with favorable outcomes after surgery alone.[95] This supports the possibility that the absence of Hsp90A in tumor biopsies may serve as a biomarker for positive clinical outcomes.[96][97] Biologically, Hsp90A differs from Hsp90B in that Hsp90A is presently understood to function as a secreted extracellular agent in wound healing and inflammation in addition to its intracellular roles. These two processes are often hijacked by cancer allowing for malignant cell motility, metastasis and extravasion.[98] Current research in prostate cancer indicates that extracellular Hsp90A transduces signals that promote the chronic inflammation of cancer-associated fibroblasts. This reprogramming of the extracellular milieu surrounding malignant adenocarcinoma cells is understood to stimulate prostate cancer progression. Extracellular HSP90A induces inflammation through the activation of the NF-κB (RELA) and STAT3 transcription programs that include the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8.[99] Coincidentally NF-κB also induces expression Hsp90A.,[14] thus providing a model where newly expressed Hsp90A would also be secreted from the stimulated fibroblast thereby creating positive autocrine and paracrine feedback loops resulting in an inflammatory storm at the site of malignancy. This concept requires further attention as it may explain the correlation of increased levels of Hsp90A in the plasma of patients with advanced stages of malignancy.[80]

Hsp90 Inhibitors

[edit]Hsp90 is exploited by cancer cells to support activated oncoproteins, including many kinases and transcription factors. These clients are often mutated, amplified or translocated in malignancy, and Hsp90 works to buffer these cellular stresses induced by malignant transformation.[90][91] Inhibition of Hsp90 leads to the degradation or instability of many of its client proteins.[100] Thus, Hsp90 has become an attractive target for cancer therapy. As with all ATPases, ATP binding and hydrolysis is essential for the chaperoning function of Hsp90 in vivo. Hsp90 inhibitors interfere with this cycle at its early stages by replacing ATP, leading to the regulated ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of most client proteins.[101][102] As such, the nucleotide binding pocket remains that most amenable to inhibitor generation.[103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117] To date, there are 23 active Hsp90 inhibitor oncology trials, and 13 HSP90 inhibitors are currently undergoing clinical evaluation in cancer patients, 10 of which have entered the clinic in the past few years.[118] While the N-terminal nucleotide-binding pocket of Hsp90 is most widely studied and thus targeted, recent studies have suggested that a second ATP-binding site is located in the Hsp90 C-terminus.[119][120][121][122][123] Targeting of this region has resulted in specific reduced Hsp90-hormone interactions and has been shown to influence Hsp90 nucleotide binding.[124][125] Although none of the C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors have yet to enter the clinic, the use of both N- and C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors in combination represents an exciting new strategy for chemotherapy. Although many of the afore-mentioned inhibitors share the same Hsp90 binding site (either N- or C-terminal), it has been shown that some of these drugs preferentially access distinct Hsp90 populations, which are differentiated by the extent of their post-translational modification.[126][127] Though no published inhibitor has yet to distinguish between Hsp90A and Hsp90B, a recent study has shown that phosphorylation of a particular residue in the Hsp90 N-terminus can provide isoform specificity to inhibitor binding,[127] thus providing an additional level of regulation for optimal Hsp90 targeting.

Notes

[edit]

The 2015 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Abbey D Zuehlke, Kristin Beebe, Len Neckers, Thomas Prince (1 October 2015). "Regulation and function of the human HSP90AA1 gene". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series. 570 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2015.06.018. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 4519370. PMID 26071189. Wikidata Q28646043. |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000080824 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000021270 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Hickey E, Brandon SE, Smale G, Lloyd D, Weber LA (Jun 1989). "Sequence and regulation of a gene encoding a human 89-kilodalton heat shock protein". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 9 (6): 2615–26. doi:10.1128/MCB.9.6.2615. PMC 362334. PMID 2527334.

- ^ Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E, Monteiro A (Dec 2005). "The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution". Genomics. 86 (6): 627–37. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. PMID 16269234.

- ^ Ozawa K, Murakami Y, Eki T, Soeda E, Yokoyama K (Feb 1992). "Mapping of the gene family for human heat-shock protein 90 alpha to chromosomes 1, 4, 11, and 14". Genomics. 12 (2): 214–20. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90368-3. PMID 1740332.

- ^ Ciocca DR, Arrigo AP, Calderwood SK (Jan 2013). "Heat shock proteins and heat shock factor 1 in carcinogenesis and tumor development: an update". Archives of Toxicology. 87 (1): 19–48. Bibcode:2013ArTox..87...19C. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0918-z. PMC 3905791. PMID 22885793.

- ^ Ullrich SJ, Moore SK, Appella E (Apr 1989). "Transcriptional and translational analysis of the murine 84- and 86-kDa heat shock proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (12): 6810–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83502-5. PMID 2708345.

- ^ Zhang SL, Yu J, Cheng XK, Ding L, Heng FY, Wu NH, Shen YF (Feb 1999). "Regulation of human hsp90alpha gene expression". FEBS Letters. 444 (1): 130–5. Bibcode:1999FEBSL.444..130Z. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00044-7. PMID 10037161.

- ^ Sreedhar AS, Kalmár E, Csermely P, Shen YF (Mar 2004). "Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance". FEBS Letters. 562 (1–3): 11–5. Bibcode:2004FEBSL.562...11S. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00229-7. PMID 15069952.

- ^ Teng SC, Chen YY, Su YN, Chou PC, Chiang YC, Tseng SF, Wu KJ (Apr 2004). "Direct activation of HSP90A transcription by c-Myc contributes to c-Myc-induced transformation" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (15): 14649–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308842200. PMID 14724288.

- ^ Perotti C, Liu R, Parusel CT, Böcher N, Schultz J, Bork P, Pfitzner E, Groner B, Shemanko CS (2008). "Heat shock protein-90-alpha, a prolactin-STAT5 target gene identified in breast cancer cells, is involved in apoptosis regulation". Breast Cancer Research. 10 (6): R94. doi:10.1186/bcr2193. PMC 2656886. PMID 19014541.

- ^ a b Ammirante M, Rosati A, Gentilella A, Festa M, Petrella A, Marzullo L, Pascale M, Belisario MA, Leone A, Turco MC (Feb 2008). "The activity of hsp90 alpha promoter is regulated by NF-kappa B transcription factors". Oncogene. 27 (8): 1175–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210716. PMID 17724475.

- ^ Chen XS, Zhang Y, Wang JS, Li XY, Cheng XK, Zhang Y, Wu NH, Shen YF (Nov 2007). "Diverse effects of Stat1 on the regulation of hsp90alpha gene under heat shock". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 102 (4): 1059–66. doi:10.1002/jcb.21342. PMID 17427945. S2CID 84261368.

- ^ Wang J, Zhuang J, Iyer S, Lin XY, Greven MC, Kim BH, Moore J, Pierce BG, Dong X, Virgil D, Birney E, Hung JH, Weng Z (Jan 2013). "Factorbook.org: a Wiki-based database for transcription factor-binding data generated by the ENCODE consortium". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (Database issue): D171–6. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1221. PMC 3531197. PMID 23203885.

- ^ Rosenbloom KR, Sloan CA, Malladi VS, Dreszer TR, Learned K, Kirkup VM, Wong MC, Maddren M, Fang R, Heitner SG, Lee BT, Barber GP, Harte RA, Diekhans M, Long JC, Wilder SP, Zweig AS, Karolchik D, Kuhn RM, Haussler D, Kent WJ (Jan 2013). "ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (Database issue): D56–63. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1172. PMC 3531152. PMID 23193274.

- ^ Euskirchen GM, Rozowsky JS, Wei CL, Lee WH, Zhang ZD, Hartman S, Emanuelsson O, Stolc V, Weissman S, Gerstein MB, Ruan Y, Snyder M (Jun 2007). "Mapping of transcription factor binding regions in mammalian cells by ChIP: comparison of array- and sequencing-based technologies". Genome Research. 17 (6): 898–909. doi:10.1101/gr.5583007. PMC 1891348. PMID 17568005.

- ^ Hudson ME, Snyder M (Dec 2006). "High-throughput methods of regulatory element discovery". BioTechniques. 41 (6): 673–681. doi:10.2144/000112322. PMID 17191608.

- ^ Zhao R, Davey M, Hsu YC, Kaplanek P, Tong A, Parsons AB, Krogan N, Cagney G, Mai D, Greenblatt J, Boone C, Emili A, Houry WA (Mar 2005). "Navigating the chaperone network: an integrative map of physical and genetic interactions mediated by the hsp90 chaperone". Cell. 120 (5): 715–27. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.024. PMID 15766533.

- ^ Echeverría PC, Bernthaler A, Dupuis P, Mayer B, Picard D (2011). "An interaction network predicted from public data as a discovery tool: application to the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machine". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e26044. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626044E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026044. PMC 3195953. PMID 22022502.

- ^ Dupuis. "Hsp90 PPI database".

- ^ Taipale M, Tucker G, Peng J, Krykbaeva I, Lin ZY, Larsen B, Choi H, Berger B, Gingras AC, Lindquist S (Jul 2014). "A quantitative chaperone interaction network reveals the architecture of cellular protein homeostasis pathways". Cell. 158 (2): 434–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.039. PMC 4104544. PMID 25036637.

- ^ Falsone SF, Gesslbauer B, Tirk F, Piccinini AM, Kungl AJ (Nov 2005). "A proteomic snapshot of the human heat shock protein 90 interactome". FEBS Letters. 579 (28): 6350–4. Bibcode:2005FEBSL.579.6350F. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.020. PMID 16263121.

- ^ Skarra DV, Goudreault M, Choi H, Mullin M, Nesvizhskii AI, Gingras AC, Honkanen RE (Apr 2011). "Label-free quantitative proteomics and SAINT analysis enable interactome mapping for the human Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 5". Proteomics. 11 (8): 1508–16. doi:10.1002/pmic.201000770. PMC 3086140. PMID 21360678.

- ^ Low JS, Fassati A (Aug 2014). "Hsp90: a chaperone for HIV-1". Parasitology. 141 (9): 1192–202. doi:10.1017/S0031182014000298. PMID 25004926. S2CID 8637871.

- ^ Smith DR, McCarthy S, Chrovian A, Olinger G, Stossel A, Geisbert TW, Hensley LE, Connor JH (Aug 2010). "Inhibition of heat-shock protein 90 reduces Ebola virus replication". Antiviral Research. 87 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.04.015. PMC 2907434. PMID 20452380.

- ^ Li J, Soroka J, Buchner J (Mar 2012). "The Hsp90 chaperone machinery: conformational dynamics and regulation by co-chaperones". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1823 (3): 624–35. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.003. PMID 21951723.

- ^ Gano JJ, Simon JA (Feb 2010). "A proteomic investigation of ligand-dependent HSP90 complexes reveals CHORDC1 as a novel ADP-dependent HSP90-interacting protein". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 9 (2): 255–70. doi:10.1074/mcp.M900261-MCP200. PMC 2830838. PMID 19875381.

- ^ Hartson SD, Matts RL (Mar 2012). "Approaches for defining the Hsp90-dependent proteome". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1823 (3): 656–67. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.013. PMC 3276727. PMID 21906632.

- ^ Taherian A, Krone PH, Ovsenek N (Feb 2008). "A comparison of Hsp90alpha and Hsp90beta interactions with cochaperones and substrates". Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 86 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1139/o07-154. PMID 18364744.

- ^ Gong Y, Kakihara Y, Krogan N, Greenblatt J, Emili A, Zhang Z, Houry WA (2009). "An atlas of chaperone-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications to protein folding pathways in the cell". Molecular Systems Biology. 5: 275. doi:10.1038/msb.2009.26. PMC 2710862. PMID 19536198.

- ^ "Hsp90Int.db". picard.ch/Hsp90Int/index.php.

- ^ Panaretou B, Siligardi G, Meyer P, Maloney A, Sullivan JK, Singh S, Millson SH, Clarke PA, Naaby-Hansen S, Stein R, Cramer R, Mollapour M, Workman P, Piper PW, Pearl LH, Prodromou C (Dec 2002). "Activation of the ATPase activity of hsp90 by the stress-regulated cochaperone aha1" (PDF). Molecular Cell. 10 (6): 1307–18. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00785-2. PMID 12504007.

- ^ a b Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Rahman S, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S (Feb 2003). "Regulation of telomerase activity and anti-apoptotic function by protein-protein interaction and phosphorylation". FEBS Letters. 536 (1–3): 180–6. Bibcode:2003FEBSL.536..180H. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00058-9. PMID 12586360.

- ^ a b Kawauchi K, Ihjima K, Yamada O (May 2005). "IL-2 increases human telomerase reverse transcriptase activity transcriptionally and posttranslationally through phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase/Akt, heat shock protein 90, and mammalian target of rapamycin in transformed NK cells". Journal of Immunology. 174 (9): 5261–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5261. PMID 15843522.

- ^ Sato S, Fujita N, Tsuruo T (Sep 2000). "Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (20): 10832–7. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710832S. doi:10.1073/pnas.170276797. PMC 27109. PMID 10995457.

- ^ Veldscholte J, Berrevoets CA, Brinkmann AO, Grootegoed JA, Mulder E (Mar 1992). "Anti-androgens and the mutated androgen receptor of LNCaP cells: differential effects on binding affinity, heat-shock protein interaction, and transcription activation". Biochemistry. 31 (8): 2393–9. doi:10.1021/bi00123a026. PMID 1540595.

- ^ Nemoto T, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Ota M (Sep 1992). "Association of the 90-kDa heat shock protein does not affect the ligand-binding ability of androgen receptor". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 42 (8): 803–12. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90088-Z. PMID 1525041. S2CID 24978960.

- ^ Stancato LF, Chow YH, Hutchison KA, Perdew GH, Jove R, Pratt WB (Oct 1993). "Raf exists in a native heterocomplex with hsp90 and p50 that can be reconstituted in a cell-free system". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (29): 21711–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)80600-0. PMID 8408024.

- ^ Dogan T, Harms GS, Hekman M, Karreman C, Oberoi TK, Alnemri ES, Rapp UR, Rajalingam K (Dec 2008). "X-linked and cellular IAPs modulate the stability of C-RAF kinase and cell motility". Nature Cell Biology. 10 (12): 1447–55. doi:10.1038/ncb1804. PMID 19011619. S2CID 6553549.

- ^ Roe SM, Ali MM, Meyer P, Vaughan CK, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH (Jan 2004). "The Mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50(cdc37)". Cell. 116 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01027-4. PMID 14718169.

- ^ Silverstein AM, Grammatikakis N, Cochran BH, Chinkers M, Pratt WB (Aug 1998). "p50(cdc37) binds directly to the catalytic domain of Raf as well as to a site on hsp90 that is topologically adjacent to the tetratricopeptide repeat binding site". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (32): 20090–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.32.20090. PMID 9685350.

- ^ a b Hulkko SM, Wakui H, Zilliacus J (Aug 2000). "The pro-apoptotic protein death-associated protein 3 (DAP3) interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor and affects the receptor function". The Biochemical Journal. 349 (3): 885–93. doi:10.1042/bj3490885. PMC 1221218. PMID 10903152.

- ^ Kang J, Kim T, Ko YG, Rho SB, Park SG, Kim MJ, Kwon HJ, Kim S (Oct 2000). "Heat shock protein 90 mediates protein-protein interactions between human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (41): 31682–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909965199. PMID 10913161.

- ^ Marcu MG, Doyle M, Bertolotti A, Ron D, Hendershot L, Neckers L (Dec 2002). "Heat shock protein 90 modulates the unfolded protein response by stabilizing IRE1alpha". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (24): 8506–13. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.24.8506-8513.2002. PMC 139892. PMID 12446770.

- ^ a b Nair SC, Toran EJ, Rimerman RA, Hjermstad S, Smithgall TE, Smith DF (Dec 1996). "A pathway of multi-chaperone interactions common to diverse regulatory proteins: estrogen receptor, Fes tyrosine kinase, heat shock transcription factor Hsf1, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 1 (4): 237–50. doi:10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001<0237:apomci>2.3.co;2 (inactive 2024-11-02). PMC 376461. PMID 9222609.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Lee MO, Kim EO, Kwon HJ, Kim YM, Kang HJ, Kang H, Lee JE (Feb 2002). "Radicicol represses the transcriptional function of the estrogen receptor by suppressing the stabilization of the receptor by heat shock protein 90". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 188 (1–2): 47–54. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00753-5. PMID 11911945. S2CID 37933406.

- ^ Nair SC, Rimerman RA, Toran EJ, Chen S, Prapapanich V, Butts RN, Smith DF (Feb 1997). "Molecular cloning of human FKBP51 and comparisons of immunophilin interactions with Hsp90 and progesterone receptor". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 17 (2): 594–603. doi:10.1128/MCB.17.2.594. PMC 231784. PMID 9001212.

- ^ Vaiskunaite R, Kozasa T, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA (Dec 2001). "Interaction between the G alpha subunit of heterotrimeric G(12) protein and Hsp90 is required for G alpha(12) signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (49): 46088–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108711200. PMID 11598136.

- ^ a b Venema RC, Venema VJ, Ju H, Harris MB, Snead C, Jilling T, Dimitropoulou C, Maragoudakis ME, Catravas JD (Aug 2003). "Novel complexes of guanylate cyclase with heat shock protein 90 and nitric oxide synthase". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 285 (2): H669–78. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01025.2002. PMID 12676772.

- ^ Xu W, Mimnaugh E, Rosser MF, Nicchitta C, Marcu M, Yarden Y, Neckers L (Feb 2001). "Sensitivity of mature Erbb2 to geldanamycin is conferred by its kinase domain and is mediated by the chaperone protein Hsp90". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (5): 3702–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006864200. PMID 11071886.

- ^ Jeong JH, An JY, Kwon YT, Li LY, Lee YJ (Oct 2008). "Quercetin-induced ubiquitination and down-regulation of Her-2/neu". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 105 (2): 585–95. doi:10.1002/jcb.21859. PMC 2575035. PMID 18655187.

- ^ Hu Y, Mivechi NF (May 2003). "HSF-1 interacts with Ral-binding protein 1 in a stress-responsive, multiprotein complex with HSP90 in vivo". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (19): 17299–306. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300788200. PMID 12621024.

- ^ Scheufler C, Brinker A, Bourenkov G, Pegoraro S, Moroder L, Bartunik H, Hartl FU, Moarefi I (Apr 2000). "Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine". Cell. 101 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. PMID 10786835.

- ^ Johnson BD, Schumacher RJ, Ross ED, Toft DO (Feb 1998). "Hop modulates Hsp70/Hsp90 interactions in protein folding". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (6): 3679–86. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.6.3679. PMID 9452498.

- ^ Harris MB, Ju H, Venema VJ, Blackstone M, Venema RC (Sep 2000). "Role of heat shock protein 90 in bradykinin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide release". General Pharmacology. 35 (3): 165–70. doi:10.1016/S0306-3623(01)00104-5. PMID 11744239.

- ^ Stepp DW, Ou J, Ackerman AW, Welak S, Klick D, Pritchard KA (Aug 2002). "Native LDL and minimally oxidized LDL differentially regulate superoxide anion in vascular endothelium in situ". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 283 (2): H750–9. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00029.2002. PMID 12124224. S2CID 30652156.

- ^ Jibard N, Meng X, Leclerc P, Rajkowski K, Fortin D, Schweizer-Groyer G, Catelli MG, Baulieu EE, Cadepond F (Mar 1999). "Delimitation of two regions in the 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) able to interact with the glucocorticosteroid receptor (GR)". Experimental Cell Research. 247 (2): 461–74. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4375. PMID 10066374.

- ^ Kanelakis KC, Shewach DS, Pratt WB (Sep 2002). "Nucleotide binding states of hsp70 and hsp90 during sequential steps in the process of glucocorticoid receptor.hsp90 heterocomplex assembly". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (37): 33698–703. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204164200. PMID 12093808.

- ^ Hecht K, Carlstedt-Duke J, Stierna P, Gustafsson J, Brönnegârd M, Wikström AC (Oct 1997). "Evidence that the beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor does not act as a physiologically significant repressor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (42): 26659–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.42.26659. PMID 9334248.

- ^ de Castro M, Elliot S, Kino T, Bamberger C, Karl M, Webster E, Chrousos GP (Sep 1996). "The non-ligand binding beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor (hGR beta): tissue levels, mechanism of action, and potential physiologic role". Molecular Medicine. 2 (5): 597–607. doi:10.1007/BF03401643. PMC 2230188. PMID 8898375.

- ^ van den Berg JD, Smets LA, van Rooij H (Feb 1996). "Agonist-free transformation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human B-lymphoma cells". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 57 (3–4): 239–49. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(95)00271-5. PMID 8645634. S2CID 20582144.

- ^ Stancato LF, Silverstein AM, Gitler C, Groner B, Pratt WB (Apr 1996). "Use of the thiol-specific derivatizing agent N-iodoacetyl-3-[125I]iodotyrosine to demonstrate conformational differences between the unbound and hsp90-bound glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (15): 8831–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.15.8831. PMID 8621522.

- ^ Wang C, Chen J (Jan 2003). "Phosphorylation and hsp90 binding mediate heat shock stabilization of p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (3): 2066–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206697200. PMID 12427754.

- ^ Akakura S, Yoshida M, Yoneda Y, Horinouchi S (May 2001). "A role for Hsc70 in regulating nucleocytoplasmic transport of a temperature-sensitive p53 (p53Val-135)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (18): 14649–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100200200. PMID 11297531.

- ^ Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J (Nov 2001). "Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (44): 40583–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102817200. PMID 11507088.

- ^ Mizuno K, Shirogane T, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Hibi M, Hirano T (Mar 2001). "Regulation of Pim-1 by Hsp90". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 281 (3): 663–9. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4405. PMID 11237709.

- ^ Sumanasekera WK, Tien ES, Turpey R, Vanden Heuvel JP, Perdew GH (Feb 2003). "Evidence that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is complexed with the 90-kDa heat shock protein and the hepatitis virus B X-associated protein 2". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (7): 4467–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M211261200. PMID 12482853.

- ^ Hamamoto R, Furukawa Y, Morita M, Iimura Y, Silva FP, Li M, Yagyu R, Nakamura Y (Aug 2004). "SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (8): 731–40. doi:10.1038/ncb1151. PMID 15235609. S2CID 13456531.

- ^ Boudeau J, Deak M, Lawlor MA, Morrice NA, Alessi DR (Mar 2003). "Heat-shock protein 90 and Cdc37 interact with LKB1 and regulate its stability". The Biochemical Journal. 370 (Pt 3): 849–57. doi:10.1042/BJ20021813. PMC 1223241. PMID 12489981.

- ^ a b Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH (Jul 2008). "Critical regulation of TGFbeta signaling by Hsp90". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (27): 9244–9. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800163105. PMC 2453700. PMID 18591668.

- ^ Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E (Jan 2015). "PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations". Nucleic Acids Research. 43 (Database issue): D512–20. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1267. PMC 4383998. PMID 25514926.

- ^ a b Muller P, Ruckova E, Halada P, Coates PJ, Hrstka R, Lane DP, Vojtesek B (Jun 2013). "C-terminal phosphorylation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 regulates alternate binding to co-chaperones CHIP and HOP to determine cellular protein folding/degradation balances". Oncogene. 32 (25): 3101–10. doi:10.1038/onc.2012.314. PMID 22824801.

- ^ Mollapour M, Tsutsumi S, Truman AW, Xu W, Vaughan CK, Beebe K, Konstantinova A, Vourganti S, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Trepel JB, Prodromou C, Pearl LH, Neckers L (Mar 2011). "Threonine 22 phosphorylation attenuates Hsp90 interaction with cochaperones and affects its chaperone activity". Molecular Cell. 41 (6): 672–81. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.011. PMC 3062913. PMID 21419342.

- ^ Mollapour M, Tsutsumi S, Neckers L (Jun 2010). "Hsp90 phosphorylation, Wee1 and the cell cycle". Cell Cycle. 9 (12): 2310–6. doi:10.4161/cc.9.12.12054. PMC 7316391. PMID 20519952.

- ^ a b Quanz M, Herbette A, Sayarath M, de Koning L, Dubois T, Sun JS, Dutreix M (Mar 2012). "Heat shock protein 90α (Hsp90α) is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage and accumulates in repair foci". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (12): 8803–15. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.320887. PMC 3308794. PMID 22270370.

- ^ Zhao YG, Gilmore R, Leone G, Coffey MC, Weber B, Lee PW (Aug 2001). "Hsp90 phosphorylation is linked to its chaperoning function. Assembly of the reovirus cell attachment protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (35): 32822–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105562200. PMID 11438552.

- ^ Xu W, Mollapour M, Prodromou C, Wang S, Scroggins BT, Palchick Z, Beebe K, Siderius M, Lee MJ, Couvillon A, Trepel JB, Miyata Y, Matts R, Neckers L (Aug 2012). "Dynamic tyrosine phosphorylation modulates cycling of the HSP90-P50(CDC37)-AHA1 chaperone machine". Molecular Cell. 47 (3): 434–43. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.015. PMC 3418412. PMID 22727666.

- ^ a b Wang X, Song X, Zhuo W, Fu Y, Shi H, Liang Y, Tong M, Chang G, Luo Y (Dec 2009). "The regulatory mechanism of Hsp90alpha secretion and its function in tumor malignancy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (50): 21288–93. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10621288W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908151106. PMC 2795546. PMID 19965370.

- ^ Lei H, Venkatakrishnan A, Yu S, Kazlauskas A (Mar 2007). "Protein kinase A-dependent translocation of Hsp90 alpha impairs endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity in high glucose and diabetes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (13): 9364–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608985200. PMID 17202141.

- ^ Yang Y, Rao R, Shen J, Tang Y, Fiskus W, Nechtman J, Atadja P, Bhalla K (Jun 2008). "Role of acetylation and extracellular location of heat shock protein 90alpha in tumor cell invasion". Cancer Research. 68 (12): 4833–42. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0644. PMC 2665713. PMID 18559531.

- ^ Yufu Y, Nishimura J, Nawata H (1992). "High constitutive expression of heat shock protein 90 alpha in human acute leukemia cells". Leukemia Research. 16 (6–7): 597–605. doi:10.1016/0145-2126(92)90008-u. PMID 1635378.

- ^ Tian WL, He F, Fu X, Lin JT, Tang P, Huang YM, Guo R, Sun L (Jun 2014). "High expression of heat shock protein 90 alpha and its significance in human acute leukemia cells". Gene. 542 (2): 122–8. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.03.046. PMID 24680776.

- ^ Jameel A, Skilton RA, Campbell TA, Chander SK, Coombes RC, Luqmani YA (Feb 1992). "Clinical and biological significance of HSP89 alpha in human breast cancer". International Journal of Cancer. 50 (3): 409–15. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910500315. PMID 1735610. S2CID 45804047.

- ^ Gress TM, Müller-Pillasch F, Weber C, Lerch MM, Friess H, Büchler M, Beger HG, Adler G (Jan 1994). "Differential expression of heat shock proteins in pancreatic carcinoma". Cancer Research. 54 (2): 547–51. PMID 8275493.

- ^ Hacker S, Lambers C, Hoetzenecker K, Pollreisz A, Aigner C, Lichtenauer M, Mangold A, Niederpold T, Zimmermann M, Taghavi S, Klepetko W, Ankersmit HJ (2009). "Elevated HSP27, HSP70 and HSP90 alpha in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: markers for immune activation and tissue destruction". Clinical Laboratory. 55 (1–2): 31–40. PMID 19350847.

- ^ Metz K, Ezernieks J, Sebald W, Duschl A (Apr 1996). "Interleukin-4 upregulates the heat shock protein Hsp90alpha and enhances transcription of a reporter gene coupled to a single heat shock element". FEBS Letters. 385 (1–2): 25–8. Bibcode:1996FEBSL.385...25M. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00341-9. PMID 8641459.

- ^ Brehme M, Voisine C, Rolland T, Wachi S, Soper JH, Zhu Y, Orton K, Villella A, Garza D, Vidal M, Ge H, Morimoto RI (2014). "A conserved chaperome sub-network safeguards protein homeostasis in aging and neurodegenerative disease". Cell Rep. 9 (3): 1135–1150. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.042. PMC 4255334. PMID 25437566.

- ^ a b Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N (Oct 2007). "Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1113 (1): 202–16. Bibcode:2007NYASA1113..202W. doi:10.1196/annals.1391.012. PMID 17513464. S2CID 8590411.

- ^ a b Trepel J, Mollapour M, Giaccone G, Neckers L (Aug 2010). "Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 10 (8): 537–49. doi:10.1038/nrc2887. PMC 6778733. PMID 20651736.

- ^ Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N (Apr 2013). "Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal". Science Signaling. 6 (269): pl1. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2004088. PMC 4160307. PMID 23550210.

- ^ Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N (May 2012). "The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data". Cancer Discovery. 2 (5): 401–4. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. PMC 3956037. PMID 22588877.

- ^ Finka A, Goloubinoff P (Sep 2013). "Proteomic data from human cell cultures refine mechanisms of chaperone-mediated protein homeostasis". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 18 (5): 591–605. doi:10.1007/s12192-013-0413-3. PMC 3745260. PMID 23430704.

- ^ Buffart TE, Carvalho B, van Grieken NC, van Wieringen WN, Tijssen M, Kranenbarg EM, Verheul HM, Grabsch HI, Ylstra B, van de Velde CJ, Meijer GA (2012). "Losses of chromosome 5q and 14q are associated with favorable clinical outcome of patients with gastric cancer". The Oncologist. 17 (5): 653–62. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0379. PMC 3360905. PMID 22531355.

- ^ Gallegos Ruiz MI, Floor K, Roepman P, Rodriguez JA, Meijer GA, Mooi WJ, Jassem E, Niklinski J, Muley T, van Zandwijk N, Smit EF, Beebe K, Neckers L, Ylstra B, Giaccone G (5 March 2008). "Integration of gene dosage and gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer, identification of HSP90 as potential target". PLOS ONE. 3 (3): e0001722. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1722G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001722. PMC 2254495. PMID 18320023.

- ^ Cheng Q, Chang JT, Geradts J, Neckers LM, Haystead T, Spector NL, Lyerly HK (17 April 2012). "Amplification and high-level expression of heat shock protein 90 marks aggressive phenotypes of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative breast cancer". Breast Cancer Research. 14 (2): R62. doi:10.1186/bcr3168. PMC 3446397. PMID 22510516.

- ^ Eustace BK, Sakurai T, Stewart JK, Yimlamai D, Unger C, Zehetmeier C, Lain B, Torella C, Henning SW, Beste G, Scroggins BT, Neckers L, Ilag LL, Jay DG (Jun 2004). "Functional proteomic screens reveal an essential extracellular role for hsp90 alpha in cancer cell invasiveness". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (6): 507–14. doi:10.1038/ncb1131. PMID 15146192. S2CID 40025264.

- ^ Bohonowych JE, Hance MW, Nolan KD, Defee M, Parsons CH, Isaacs JS (Apr 2014). "Extracellular Hsp90 mediates an NF-κB dependent inflammatory stromal program: implications for the prostate tumor microenvironment". The Prostate. 74 (4): 395–407. doi:10.1002/pros.22761. PMC 4306584. PMID 24338924.

- ^ Blagg BS, Kerr TD (May 2006). "Hsp90 inhibitors: small molecules that transform the Hsp90 protein folding machinery into a catalyst for protein degradation". Medicinal Research Reviews. 26 (3): 310–38. doi:10.1002/med.20052. PMID 16385472. S2CID 13316474.

- ^ Eleuteri AM, Cuccioloni M, Bellesi J, Lupidi G, Fioretti E, Angeletti M (Aug 2002). "Interaction of Hsp90 with 20S proteasome: thermodynamic and kinetic characterization". Proteins. 48 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1002/prot.10101. PMID 12112686. S2CID 37257142.

- ^ Theodoraki MA, Caplan AJ (Mar 2012). "Quality control and fate determination of Hsp90 client proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1823 (3): 683–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.006. PMC 3242914. PMID 21871502.

- ^ Whitesell L, Mimnaugh EG, De Costa B, Myers CE, Neckers LM (Aug 1994). "Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (18): 8324–8. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.8324W. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. PMC 44598. PMID 8078881.

- ^ Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH (Jul 1997). "Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone". Cell. 90 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. PMID 9230303.

- ^ Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP (Apr 1997). "Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent". Cell. 89 (2): 239–50. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. PMID 9108479.

- ^ Grenert JP, Sullivan WP, Fadden P, Haystead TA, Clark J, Mimnaugh E, Krutzsch H, Ochel HJ, Schulte TW, Sausville E, Neckers LM, Toft DO (Sep 1997). "The amino-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) that binds geldanamycin is an ATP/ADP switch domain that regulates hsp90 conformation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (38): 23843–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.38.23843. PMID 9295332.

- ^ Sharma SV, Agatsuma T, Nakano H (May 1998). "Targeting of the protein chaperone, HSP90, by the transformation suppressing agent, radicicol". Oncogene. 16 (20): 2639–45. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201790. PMID 9632140.

- ^ Schulte TW, Akinaga S, Soga S, Sullivan W, Stensgard B, Toft D, Neckers LM (Jun 1998). "Antibiotic radicicol binds to the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 3 (2): 100–8. doi:10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0100:arbttn>2.3.co;2 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMC 312953. PMID 9672245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Banerji U, Walton M, Raynaud F, Grimshaw R, Kelland L, Valenti M, Judson I, Workman P (Oct 2005). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in human ovarian cancer xenograft models". Clinical Cancer Research. 11 (19 Pt 1): 7023–32. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0518. PMID 16203796.

- ^ Chiosis G, Tao H (Nov 2006). "Purine-scaffold Hsp90 inhibitors". IDrugs: The Investigational Drugs Journal. 9 (11): 778–82. PMID 17096299.

- ^ Eccles SA, Massey A, Raynaud FI, Sharp SY, Box G, Valenti M, Patterson L, de Haven Brandon A, Gowan S, Boxall F, Aherne W, Rowlands M, Hayes A, Martins V, Urban F, Boxall K, Prodromou C, Pearl L, James K, Matthews TP, Cheung KM, Kalusa A, Jones K, McDonald E, Barril X, Brough PA, Cansfield JE, Dymock B, Drysdale MJ, Finch H, Howes R, Hubbard RE, Surgenor A, Webb P, Wood M, Wright L, Workman P (Apr 2008). "NVP-AUY922: a novel heat shock protein 90 inhibitor active against xenograft tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis". Cancer Research. 68 (8): 2850–60. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5256. PMID 18413753.

- ^ Kummar S, Gutierrez ME, Gardner ER, Chen X, Figg WD, Zajac-Kaye M, Chen M, Steinberg SM, Muir CA, Yancey MA, Horneffer YR, Juwara L, Melillo G, Ivy SP, Merino M, Neckers L, Steeg PS, Conley BA, Giaccone G, Doroshow JH, Murgo AJ (Jan 2010). "Phase I trial of 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG), a heat shock protein inhibitor, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced malignancies". European Journal of Cancer. 46 (2): 340–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.10.026. PMC 2818572. PMID 19945858.

- ^ Lancet JE, Gojo I, Burton M, Quinn M, Tighe SM, Kersey K, Zhong Z, Albitar MX, Bhalla K, Hannah AL, Baer MR (Apr 2010). "Phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (KOS-1022, 17-DMAG) administered intravenously twice weekly to patients with acute myeloid leukemia". Leukemia. 24 (4): 699–705. doi:10.1038/leu.2009.292. PMID 20111068.

- ^ Pacey S, Wilson RH, Walton M, Eatock MM, Hardcastle A, Zetterlund A, Arkenau HT, Moreno-Farre J, Banerji U, Roels B, Peachey H, Aherne W, de Bono JS, Raynaud F, Workman P, Judson I (Mar 2011). "A phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (17-DMAG) given intravenously to patients with advanced solid tumors". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (6): 1561–70. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1927. PMC 3060938. PMID 21278242.

- ^ Jhaveri K, Modi S (2012). "HSP90 inhibitors for cancer therapy and overcoming drug resistance". Current Challenges in Personalized Cancer Medicine. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 65. pp. 471–517. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00015-4. ISBN 978-0-12-397927-8. PMID 22959035.

- ^ Jego G, Hazoumé A, Seigneuric R, Garrido C (May 2013). "Targeting heat shock proteins in cancer". Cancer Letters. 332 (2): 275–85. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.014. PMID 21078542.

- ^ Taldone T, Ochiana SO, Patel PD, Chiosis G (Nov 2014). "Selective targeting of the stress chaperome as a therapeutic strategy". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 35 (11): 592–603. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.001. PMC 4254259. PMID 25262919.

- ^ Neckers L, Trepel JB (Jan 2014). "Stressing the development of small molecules targeting HSP90". Clinical Cancer Research. 20 (2): 275–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2571. PMID 24166908.

- ^ Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, Prohászka Z, Nardai G (Aug 1998). "The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 79 (2): 129–68. doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00013-8. PMID 9749880.

- ^ Marcu MG, Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Catelli M, Neckers LM (Nov 2000). "The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (47): 37181–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003701200. PMID 10945979.

- ^ Garnier C, Lafitte D, Tsvetkov PO, Barbier P, Leclerc-Devin J, Millot JM, Briand C, Makarov AA, Catelli MG, Peyrot V (Apr 2002). "Binding of ATP to heat shock protein 90: evidence for an ATP-binding site in the C-terminal domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (14): 12208–14. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111874200. PMID 11805114.

- ^ Soti C, Vermes A, Haystead TA, Csermely P (Jun 2003). "Comparative analysis of the ATP-binding sites of Hsp90 by nucleotide affinity cleavage: a distinct nucleotide specificity of the C-terminal ATP-binding site". European Journal of Biochemistry. 270 (11): 2421–8. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03610.x. PMID 12755697.

- ^ Matts RL, Dixit A, Peterson LB, Sun L, Voruganti S, Kalyanaraman P, Hartson SD, Verkhivker GM, Blagg BS (Aug 2011). "Elucidation of the Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitor binding site". ACS Chemical Biology. 6 (8): 800–7. doi:10.1021/cb200052x. PMC 3164513. PMID 21548602.

- ^ Sreedhar AS, Soti C, Csermely P (Mar 2004). "Inhibition of Hsp90: a new strategy for inhibiting protein kinases". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1697 (1–2): 233–42. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.027. PMID 15023364.

- ^ Rosenhagen MC, Sōti C, Schmidt U, Wochnik GM, Hartl FU, Holsboer F, Young JC, Rein T (Oct 2003). "The heat shock protein 90-targeting drug cisplatin selectively inhibits steroid receptor activation". Molecular Endocrinology. 17 (10): 1991–2001. doi:10.1210/me.2003-0141. PMID 12869591.

- ^ Moulick K, Ahn JH, Zong H, Rodina A, Cerchietti L, Gomes DaGama EM, Caldas-Lopes E, Beebe K, Perna F, Hatzi K, Vu LP, Zhao X, Zatorska D, Taldone T, Smith-Jones P, Alpaugh M, Gross SS, Pillarsetty N, Ku T, Lewis JS, Larson SM, Levine R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Guzman ML, Nimer SD, Melnick A, Neckers L, Chiosis G (Nov 2011). "Affinity-based proteomics reveal cancer-specific networks coordinated by Hsp90". Nature Chemical Biology. 7 (11): 818–26. doi:10.1038/nchembio.670. PMC 3265389. PMID 21946277.

- ^ a b Beebe K, Mollapour M, Scroggins B, Prodromou C, Xu W, Tokita M, Taldone T, Pullen L, Zierer BK, Lee MJ, Trepel J, Buchner J, Bolon D, Chiosis G, Neckers L (Jul 2013). "Posttranslational modification and conformational state of heat shock protein 90 differentially affect binding of chemically diverse small molecule inhibitors". Oncotarget. 4 (7): 1065–74. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1099. PMC 3759666. PMID 23867252.

Further reading

[edit]- Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, Prohászka Z, Nardai G (Aug 1998). "The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 79 (2): 129–68. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(98)00013-8. PMID 9749880.

- Young JC, Moarefi I, Hartl FU (Jul 2001). "Hsp90: a specialized but essential protein-folding tool". The Journal of Cell Biology. 154 (2): 267–73. doi:10.1083/jcb.200104079. PMC 2150759. PMID 11470816.

- Hamblin AD, Hamblin TJ (Dec 2005). "Functional and prognostic role of ZAP-70 in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 9 (6): 1165–78. doi:10.1517/14728222.9.6.1165. PMID 16300468. S2CID 20808988.

- Lattouf JB, Srinivasan R, Pinto PA, Linehan WM, Neckers L (Nov 2006). "Mechanisms of disease: the role of heat-shock protein 90 in genitourinary malignancy". Nature Clinical Practice Urology. 3 (11): 590–601. doi:10.1038/ncpuro0604. PMID 17088927. S2CID 23054181.

![1uy9: HUMAN HSP90-ALPHA WITH 8-BENZO[1,3]DIOXOL-,5-YLMETHYL-9-BUTYL-9H-PURIN-6-YLAMINE](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/PDB_1uy9_EBI.jpg/180px-PDB_1uy9_EBI.jpg)

![1uyk: HUMAN HSP90-ALPHA WITH 8-BENZO[1,3]DIOXOL-,5-YLMETHYL-9-BUT YL-2-FLUORO-9H-PURIN-6-YLAMINE](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/PDB_1uyk_EBI.jpg/180px-PDB_1uyk_EBI.jpg)