Henry Molaison

Henry Molaison | |

|---|---|

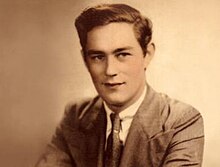

Molaison in 1953 before his surgery | |

| Born | Henry Gustav Molaison February 26, 1926 Manchester, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 2008 (aged 82) |

Henry Gustav Molaison (February 26, 1926 – December 2, 2008), known widely as H.M., was an American who had a bilateral medial temporal lobectomy to surgically resect the anterior two thirds of his hippocampi, parahippocampal cortices, entorhinal cortices, piriform cortices, and amygdalae in an attempt to cure his epilepsy. Although the surgery was partially successful in controlling his epilepsy, a severe side effect was that he became unable to form new memories. His unique case also helped define ethical standards in neurological research, emphasizing the need for patient consent and the consideration of long-term impacts of medical interventions. Furthermore, Molaison's life after his surgery highlighted the challenges and adaptations required for living with significant memory impairments, serving as an important case study for healthcare professionals and caregivers dealing with similar conditions.

A childhood bicycle accident[note 1] is often advanced as the likely cause of H.M.'s epilepsy.[1] H.M. began to have minor seizures at age 10; from 16 years of age, the seizures became major. Despite high doses of anticonvulsant medication, H.M.'s seizures were incapacitating. When he was 27, H.M. was offered an experimental procedure by neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville. Previously Scoville had only ever performed the surgery on psychotic patients.

The surgery took place in 1953 and H.M. was widely studied from late 1957 until his death in 2008.[2][3] He resided in a care institute in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, where he was the subject of ongoing investigation.[4] His case played an important role in the development of theories that explain the link between brain function and memory, and in the development of cognitive neuropsychology, a branch of psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes.[5][6][7][8][9]

Molaison's brain was kept at University of California, San Diego, where it was sliced into histological sections on December 4, 2009.[10] It was later moved to the MIND Institute at UC Davis.[11] The brain atlas constructed was made publicly available in 2014.[12][13]

Biography

[edit]

Henry Molaison was born on February 26, 1926, in Manchester, Connecticut, and experienced intractable epilepsy that has sometimes been attributed to a bicycle accident at the age of seven.[note 1] He had minor or partial seizures for many years, and then major or tonic-clonic seizures following his 16th birthday. He worked for a time on an assembly line but, by the age of 27, he had become so incapacitated by his seizures, despite high doses of anticonvulsant medication, that he could not work nor lead a normal life.

In 1953, Molaison was referred to William Beecher Scoville, a neurosurgeon at Hartford Hospital.[3] Scoville localized his epilepsy to the left and right medial temporal lobes (MTLs) and suggested their surgical resection. On September 1, 1953, Scoville removed Molaison's medial temporal lobes on both hemispheres including the hippocampi and most of the amygdalae and entorhinal cortex, the major sensory input to the hippocampi.[14] His hippocampi appeared entirely nonfunctional because the remaining 2 cm of hippocampal tissue appeared to have atrophied and some of his anterolateral temporal cortex was also destroyed.

After the surgery, which was partially successful in controlling his seizures, Molaison developed severe anterograde amnesia: although his working memory and procedural memory were intact, he could not commit new events to his explicit memory. According to some scientists, he was impaired in his ability to form new semantic knowledge.[15]

Researchers argue over the extent of this impairment. He also had moderate retrograde amnesia, and could not remember most events in the one- to two-year period before surgery, nor some events up to 11 years before, meaning that his amnesia was temporally graded.

His case was first reported by Scoville and Brenda Milner in 1957, who referred to him by "H.M."[14] His full name was not revealed to the wider public until after his death.[11] While researchers had told him of the significance of his condition and of his renown within the world of neurological research, he was unable to internalize such facts as memories.[11]

Near the end of his life, Molaison regularly filled in crossword puzzles.[16] He was able to fill in answers to clues that referred to pre-1953 knowledge. For post-1953 information he was able to modify old memories with new information. For instance, he could add a memory about Jonas Salk by modifying his memory of polio.[2]

Insights into memory formation

[edit]Molaison was influential not only for the knowledge he provided about memory impairment and amnesia, but also because it was thought his exact brain surgery allowed a good understanding of how particular areas of the brain may be linked to specific processes hypothesized to occur in memory formation. In this way, his case was taken to provide information about brain pathology, and helped to form theories of normal memory function.

In particular, his apparent ability to complete tasks that require recall from short-term memory and procedural memory but not long-term episodic memory suggests that recall from these memory systems may be mediated, at least in part, by different areas of the brain. Similarly, his ability to recall long-term memories that existed well before his surgery, but inability to create new long-term memories, suggests that encoding and retrieval of long-term memory information may also be mediated by distinct systems.

Nevertheless, imaging of Molaison's brain in the late 1990s revealed the extent of damage was more widespread than previous theories had accounted for, making it very hard to identify any one particular region or even isolated set of regions that were responsible for HM's deficits.[17]

Contribution to science

[edit]The study of Molaison revolutionized the understanding of the organization of human memory. It has provided broad evidence for the rejection of old theories and the formation of new theories on human memory, in particular about its processes and the underlying neural structures.[18] In the following, some of the major insights are outlined.

Molaison's brain was the subject of an anatomical study funded by the Dana Foundation and the National Science Foundation. The aim of the project, headed by Jacopo Annese, of The Brain Observatory at UC San Diego, was to provide a complete microscopic survey of the entire brain to reveal the neurological basis of Molaison's historical memory impairment at cellular resolution. On December 4, 2009, Annese's group acquired 2401 brain slices, with only two damaged slices and 16 potentially problematic slices.[19] The digital 3D reconstruction of his brain was finished at the beginning of 2014.[20]

The results of the study were published in Nature Communications for January 2014. The researchers found, to their surprise, that half of H.M.'s hippocampal tissue had survived the 1953 surgery, which has deep implications on past and future interpretations of H.M.'s neurobehavioral profile and of the previous literature describing H.M. as a "pure" hippocampus lesion patient. Additionally, a previously unexpected discrete lesion was discovered in the prefrontal cortex. These findings suggest revisiting raw data from behavioral testing. A three-dimensional virtual model of the brain allowed the dynamics of the surgery to be reconstructed; it was found that the brain damage above the left orbit could have been created by Dr. Scoville when he lifted the frontal lobe to reach into the medial temporal lobes.

The article also describes the general neuropathological state of the brain via multiple imaging modalities. As H.M. was 82 when he died, his brain had aged considerably. Several pathological features were discovered, some severe, which had contributed to his cognitive decline.[21]

The digital atlas of HM's brain was made publicly available on the Internet free of charge.[13]

Amnesia

[edit]Molaison's general condition has been described as heavy anterograde amnesia, as well as temporally graded retrograde amnesia. Since Molaison did not show any memory impairment before the surgery, the removal of the medial temporal lobes can be held responsible for his memory disorder. Consequently, the medial temporal lobes can be assumed to be a major component involved in the formation of semantic and episodic long-term memories (cf. medial temporal lobes described as a convergence zone for episodic encoding in Smith & Kosslyn, 2007). Further evidence for this assumption has been gained by studies of other patients with lesions of their medial temporal lobe structures.[14]

Despite his amnesic symptoms, Molaison performed quite normally in tests of intellectual ability, indicating that some memory functions (e.g., short-term memories, stores for words, phonemes, etc.) were not impaired by the surgery. However, for sentence-level language comprehension and production, Molaison exhibited the same deficits and sparing as in memory. Molaison was able to remember information over short intervals of time. This was tested in a working memory experiment involving the recall of previously presented numbers; in fact, his performance was no worse than that of control subjects (Smith & Kosslyn, 2007). This finding provides evidence that working memory does not rely on medial temporal structures. Molaison's largely intact word retrieval provides evidence that lexical memory is independent of the medial temporal structures.

Motor skill learning

[edit]In addition to his intact working memory and intellectual abilities, studies of Molaison's ability to acquire new motor skills contributed to a demonstrated preserved motor learning[8] (Corkin, 2002). In a study conducted by Milner in the early 1960s, Molaison acquired the new skill of drawing a figure by looking at its reflection in a mirror (Corkin, 2002). Specifically, H.M. was asked to trace a 3rd star in the narrow space between 2 concentric stars while only looking at a reflection of his paper and pencil in a mirror. Like most people performing this task for the first time, he did not do well and went outside the lines about 30 times. Milner had him do this task 10 times on each day and saw that the number of errors he made went down for each trial after the first. H.M. made about 20 errors on the second trial, 12 errors on the third, and by the 10th trial on the first day he only made about 5-6 errors. Each time H.M. performed the task, he improved even though he had no memory of the previous attempts or of ever doing the task. On the second day, he made significantly fewer errors for each trial on average, and on the third day he made almost no errors for each trial. Milner concluded that the unconscious motor centers and parts of the brain responsible for procedural implicit memory such as the basal ganglia and cerebellum can remember things that the conscious mind has forgotten. These structures were intact in H.M.’s brain, and thus he was able to do well on this task after repeated trials.

Further evidence for intact motor learning was provided in a study carried out by Corkin (1968). In this study, Molaison was tested on three motor learning tasks and demonstrated full motor learning abilities in all of them.

Experiments involving repetition priming underscored Molaison's ability to acquire implicit (non-conscious) memories, in contrast to his inability to acquire new explicit semantic and episodic memories (Corkin, 2002). These findings provide evidence that memory of skills and repetition priming rely on different neural structures than memories of episodes and facts; whereas procedural memory and repetition priming do not rely on the medial temporal structures removed from Molaison, semantic and episodic memory do (cf. Corkin, 1984).

The dissociation of Molaison's implicit and explicit learning abilities along their underlying neural structures has served as an important contribution to our understanding of human memory: Long-term memories are not unitary and can be differentiated as being either declarative or non-declarative (Smith & Kosslyn, 2007).

Spatial memory

[edit]According to Corkin (2002),[22] studies of Molaison's memory abilities have also provided insights regarding the neural structures responsible for spatial memory and processing of spatial information. Despite his general inability to form new episodic or factual long-term memories, as well as his heavy impairment on certain spatial memory tests, Molaison was able to draw a quite detailed map of the topographical layout of his residence. This finding is remarkable since Molaison had moved to the house five years after his surgery and hence, given his severe anterograde amnesia and insights from other cases, the common expectation was that the acquisition of topographical memories would have been impaired as well. Corkin (2002) hypothesized that Molaison "was able to construct a cognitive map of the spatial layout of his house as the result of daily locomotion from room to room" (p. 156).[22]

Regarding the underlying neural structures, Corkin (2002)[22] argues that Molaison's ability to acquire the floor plan is due to partly intact structures of his spatial processing network (e.g., the posterior part of his parahippocampal gyrus). In addition to his topographical memory, Molaison showed some learning in a picture memorization-recognition task, as well as in a famous faces recognition test, but in the latter only when he was provided with a phonemic cue. Molaison's positive performance in the picture recognition task might be due to spared parts of his ventral perirhinal cortex.[22]

Furthermore, Corkin (2002)[22] argues that despite Molaison's general inability to form new declarative memories, he seemed to be able to acquire small and impoverished pieces of information regarding public life (e.g., cued retrieval of celebrities' names). These findings underscore the importance of Molaison's spared extrahippocampal sites in semantic and recognition memory and enhance our understanding of the interrelations between the different medial temporal lobe structures. Molaison's heavy impairment in certain spatial tasks provides further evidence for the association of the hippocampi with spatial memory.[23][24]

Memory consolidation

[edit]Another contribution of Molaison to understanding of human memory regards the neural structures of the memory consolidation process, which is responsible for forming stable long-term memories (Eysenck & Keane, 2005). Molaison displayed a temporally graded retrograde amnesia in the way that he "could still recall childhood memories, but he had difficulty remembering events that happened during the years immediately preceding the surgery".[25] His old memories were not impaired, whereas the ones relatively close to the surgery were. This is evidence that the older childhood memories do not rely on the medial temporal lobe, whereas the more recent long-term memories seem to do so.[25] The medial temporal structures, which were removed in the surgery, are hypothesized to be involved in the consolidation of memories in the way that "interactions between the medial temporal lobe and various lateral cortical regions are thought to store memories outside the medial temporal lobes by slowly forming direct links between the cortical representations of the experience".[25]

Post-death controversy

[edit]On August 7, 2016, a New York Times article written by Luke Dittrich, grandson of Molaison's neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville, raised a number of concerns about how Molaison's data and consent process had been conducted by the primary scientist investigating him, Suzanne Corkin. The article suggested that Corkin had destroyed research documents and data, and failed to obtain consent from Molaison's closest living kin.[11] In response to the article, a group of over 200 leading neuroscientists signed a public letter arguing that the article was biased and misleading,[26] and MIT published a rebuttal of some of the allegations in Dittrich's article.[27] This was in turn rebutted by Dittrich, who provided a recording of the interview with Corkin, where she said she had destroyed large amounts of data and files specifically related to H.M.[28][29] A second rebuttal was issued on 20 of August 2016 responding to the criticism leveled against Corkin, including the fact that in this same recorded interview Corkin says that when moving lab locations in the past, other files and data had been discarded, while temporarily “We kept the H.M. stuff”.[30]

Psychologist Stuart Vyse writes about this controversy and the action of the two hundred scientists who responded to criticism of Corkin. Vyse states that in their rush to defend Corkin they risked their credibility and authority "by weighing in on subjects outside their circle of knowledge". The "signers responded very quickly" only two days after the release of the NYT article, they were not aware of the "specific claims of bias" and very few of the signers "could have had relevant knowledge of the facts". Consensus of the science is important, but the consensus should be based on actual knowledge of the subject and not as a reaction to "come to the defense of a beloved colleague".[31]

In popular culture

[edit]Baxendale (2004) cites Molaison's life as a partial inspiration for Christopher Nolan's 2000 film Memento, the influence of which led to its realistic portrayal of anterograde amnesia.[32]

See also

[edit]- Cognitive neuropsychology

- Kent Cochrane, a similar patient who lost episodic memory after a motorcycle crash

- Clive Wearing, whose amnesia appeared after an infection

- Phineas Gage, a 19th-century railroad worker who survived an accident where a metal rod went through his brain

- Cenn Fáelad mac Ailella, a 7th-century Irish scholar who developed an extremely strong memory after a head injury

- Dark Matters: Twisted But True, an episode featured Henry Molaison's case.

- S.M., a patient who lost her ability to fear due to bilateral amygdala destruction

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Corkin, Suzanne (1984). "Lasting consequences of bilateral medial temporal lobectomy: Clinical course and experimental findings in H.M.". Seminars in Neurology. 4 (2). New York, NY: Thieme-Stratton Inc.: 249–259. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041556. S2CID 71384121.

- ^ a b Benedict Carey (December 6, 2010). "No Memory, but He Filled In the Blanks". New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Benedict Carey (December 4, 2008). "H. M., an Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82". New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Schaffhausen, Joanna. "Henry Right Now". The Day His World Stood Still. BrainConnection.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Squire, Larry R. (January 2009). "The Legacy of Patient H.M. for Neuroscience". Neuron. 61 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023. PMC 2649674. PMID 19146808.

- ^ Pattanayak, RamanDeep; Sagar, Rajesh; Shah, Bigya (2014). "The study of patient henry Molaison and what it taught us over past 50 years: Contributions to neuroscience". Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour. 19 (2): 91. doi:10.4103/0971-8990.153719. S2CID 143575922.

- ^ Dossani, Rimal Hanif; Missios, Symeon; Nanda, Anil (October 2015). "The Legacy of Henry Molaison (1926–2008) and the Impact of His Bilateral Mesial Temporal Lobe Surgery on the Study of Human Memory". World Neurosurgery. 84 (4): 1127–1135. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.04.031. PMID 25913428.

- ^ a b Levy, Adam (January 14, 2021). "Memory, the mystery". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-011421-3. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L. (2000). "Understanding implicit memory: A cognitive neuroscience approach". In Gazzaniga, M.S. (ed.). Cognitive Neuroscience: A Reader. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21659-9.

- ^ Arielle Levin Becker (November 29, 2009). "Researchers To Study Pieces Of Unique Brain". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Luke Dittrich (August 3, 2016). "The Brain That Couldn't Remember". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ Greg Miller (January 28, 2014). "Scientists Digitize Psychology's Most Famous Brain". Wired. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Patient HM". The Institute for Brain and Society. Retrieved August 25, 2016. Atlas available without charge on request.

- ^ a b c William Beecher Scoville and Brenda Milner (1957). "Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 20 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. PMC 497229. PMID 13406589.

- ^ Schmolck, Kensinger, Corkin, & Squire, 2002

- ^ "The Man Who Couldn't Remember". NOVA scienceNOW. June 1, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Corkin, Susanna; Amaral, David G.; González, R. Gilberto; Johnson, Keith A.; Hyman, Bradley T. (May 15, 1997). "H. M.'s Medial Temporal Lobe Lesion: Findings from Magnetic Resonance Imaging". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (10): 3964–3979. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03964.1997. PMC 6573687. PMID 9133414. S2CID 15894428.

- ^ Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (February 1998). "Brain Plasticity and Behavior". Annual Review of Psychology. 49 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.43. hdl:2027.42/74427. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 9496621.

- ^ Worth, Rhian; Annese, Jacopo (2012). "Brain Observatory and the Continuing Study of H.M.: Interview with Jacopo Annese". Europe's Journal of Psychology. 8 (2): 222–230. doi:10.5964/ejop.v8i2.475. ISSN 1841-0413.

- ^ Moll, Maryanne (January 29, 2014). "Henry Molaison's (or HM) brain digitized to show how amnesia affects the brain". TechTimes. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ Annese, Jacopo; Schenker-Ahmed, Natalie M.; Bartsch, Hauke; Maechler, Paul; Sheh, Colleen; Thomas, Natasha; Kayano, Junya; Ghatan, Alexander; Bresler, Noah; Frosch, MatthewP.; Klaming, Ruth; Corkin, Suzanne (2014). "Postmortem examination of patient H.M.'s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction". Nature Communications. 5: 3122. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3122A. doi:10.1038/ncomms4122. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3916843. PMID 24473151.

- ^ a b c d e Corkin, Suzanne (February 2002). "What's new with the amnesic patient H.M.?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 3 (2): 153–160. doi:10.1038/nrn726. ISSN 1471-0048. PMID 11836523.

- ^ Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (July 2009). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-9586-5.

- ^ Anand, Kuljeet Singh; Dhikav, Vikas (December 2012). "Hippocampus in health and disease: An overview". Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 15 (4): 239–246. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.104323. ISSN 0972-2327. PMC 3548359. PMID 23349586.

- ^ a b c Smith; et al. (2007). Cognitive Psychology: Mind and Brain. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-182508-6.

- ^ Kensinger, Howard Eichenbaum and Elizabeth (September 30, 2016). "In Defense of Suzanne Corkin". APS Observer. 29 (8).

- ^ "Letters/Statement Submitted to the New York Times on August 9, 2016 from Prof. James J. Dicarlo, Head, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT". Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. Brain and Cognitive Sciences. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Dittrich, Luke (August 10, 2016). "Questions & Answers about "Patient H.M."". Medium. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Sharon Begley (August 10, 2016). "MIT Challenges The New York Times over Book on Famous Brain Patient". Scientific American.

- ^ "Additional information as of August 20, 2016, further rebutting Luke Dittrich's allegations against Professor Corkin | Brain and Cognitive Sciences". Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Vyse, Stuart (2017). "Consensus: Could Two Hundred Scientists Be Wrong?". Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (1). Committee for Skeptical Inquirer: 29–31.

- ^ Baxendale, Sallie (December 18, 2004). "Memories aren't made of this: amnesia at the movies". BMJ. 329 (7480): 1480–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1480. PMC 535990. PMID 15604191.

Further reading

[edit]Articles

[edit]- S. Corkin (2002). "What's new with the amnesic patient H.M.?" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 3 (2): 153–160. doi:10.1038/nrn726. PMID 11836523. S2CID 5429133. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2004.

- H. Schmolck; E.A. Kensinger; S. Corkin; L. Squire (2002). "Semantic knowledge in Patient H.M. and other patients with bilateral medial and lateral temporal lobe lesions" (PDF). Hippocampus. 12 (4): 520–533. doi:10.1002/hipo.10039. PMID 12201637. S2CID 9265966.

- S. Corkin (1984). "Lasting consequences of bilateral medial temporal lobectomy: Clinical course and experimental findings in H.M.". Seminars in Neurology. 4 (2): 249–259. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041556. S2CID 71384121.

- D.G. MacKay James, L.E., J. K. Taylor & Marian, D.E. (2007). "Amnesic H.M. exhibits parallel deficits and sparing in language and memory: Systems versus binding theory accounts". Language and Cognitive Processes. 22 (3): 377–452. doi:10.1080/01690960600652596. S2CID 59365387.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S. Corkin; D. G. Amaral; R. G. González; K. A. Johnson; B. T. Hyman (1997). "H. M.'s medial temporal lobe lesion: Findings from magnetic resonance imaging". The Journal of Neuroscience (17): 3, 964–3, 979.

- S. Corkin (1968). "Acquisition of motor skill after bilateral medial temporal-lobe excision". Neuropsychologia. 6 (3): 255–265. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(68)90024-9.

Books

[edit]- Philip J. Hilts (1996). Memory's Ghost. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82356-X. Provides further discussion of the author's meetings with HM.

- Suzanne Corkin (2013). Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H. M.. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465031597.

- Luke Dittrich (2017). Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets. Random House Publishing. ISBN 978-0812982527.

Textbooks

[edit]- M. W. Eysenck; M. T. Keane (2005). Cognitive Psychology: A Student's Handbook (5th ed.). Hove, UK: Psychology Press. ISBN 0-86377-375-3.

- E. E. Smith; S. M. Kosslyn (2007). Cognitive Psychology: Mind and Brain (1st ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-182508-6.

- B. Kolb; I. Q. Whishaw; I. Q. (1996). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology (4th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

External links

[edit]- What happens when you remove the hippocampus? – TED-Ed video on HM case

- The Day His World Stood Still – Article on HM from Brain Connection

- H.M.'s Brain and the History of Memory – NPR Piece on HM

- HM – The Man Who Couldn't Remember – BBC Radio 4 documentary, broadcast on August 11, 2010. Features interviews with HM himself and his carers, Dr Brenda Milner, Professor Suzanne Corkin, and Dr Jacopo Annese

- Remembering Henry Molaison, the Man Who Kept Forgetting, Science Friday, August 12, 2016

- The Untold Story of Neuroscience's Most Famous Brain, Wired, August 9, 2016

- Project H.M. – The Brain Observatory

- Remembering: What 50 Years of Research with Famous Amnesia Patient H.M. Can Teach Us about Memory and How it Works (2019) Donald G. MacKay professor emeritus of psychology at UCLA and founder of its Cognition and Aging Lab. "New and Notable". Skeptical Inquirer. 43 (4): 62–63. 2019.