Gustave Duchesne de Bellecourt

Gustave Duchesne, Prince de Bellecourt (1817 – 1881) was a French diplomat who was active in Asia, and especially in Japan. He was the first French official representative in Japan from 1859 to 1864, following the signature of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan in 1858.[1]

China

[edit]Gustave de Bellecourt was Secretary of the French legation in China in 1857, under Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros. He participated to the operation against China in the Second Opium War.[2] In 1858, Gustave Duchesne de Bellecourt arrived in Japan as the secretary of the mission for the Franco-Japanese Treaty of Trade and Amity, led by Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros.

Japan career

[edit]The following year, he went again to Japan, arriving on 6 September 1859,[3] and became the first French representative in the country,[4] with the title of "Premier ministre plénipotentiaire de France au Japon". He was assisted by the translator Father Girard. Duchesne de Bellecourt played an important political role in Japan in the late 1850s and 1860s, alongside fellow Western diplomats Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek, Townsend Harris, Rutherford Alcock and Max von Brandt. Although these men were bound by personal friendship, national rivalries and differences in dealing with the Japanese led to conflict and antagonism. However, the chaotic and ungovernable circumstances of the first few years forced them to cooperate.[5]

In 1860, the servant of Duchesne was attacked with a sword and badly wounded in front of the French legation at the Temple of Saikai-ji in Edo.[6]

In 1861, Duchesne was promoted to the position of ambassador. He was generally in agreement with Rutherford Alcock in his positions against the Bakufu.

In 1863, Duchesne was involved in the negotiations for the reparations following the Namamugi incident, in which foreigners were killed by a party from Satsuma.[7]

Duchesne, who had been a witness to Western interventions in China, was a strong advocate of the use of force to govern relations with Japan. He supported the French intervention in the 20 July 1863 Bombardment of Shimonoseki by Captain Benjamin Jaurès and the August 1863 armed intervention of the British in the Bombardment of Kagoshima.[8]

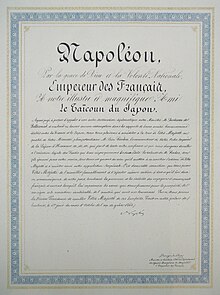

Forefront: French interpreter Blekman, Japanese interpreter.

Background (from left to right): Three Japanese governors of Yokohama, Duchesne de Bellecourt, daimyō Sakai-Hida-no-Kami, Colonel Neale (British representative in Japan), Admiral Jaurès, Admiral Kuper.

Duchesne however was strongly criticized by the French government for taking such bellicose steps, for the reason that France had much more important military commitments to honour in other parts of the world, and could not afford a conflict in Japan.[8]

In 1864, Duchesne de Bellecourt was succeeded at his post in Tokyo by Léon Roches, heralding an era of much stronger involvement by France.[9][10]

Tunisia career

[edit]Duchesne de Bellecourt was to be sent to Tunis, as Consul-General.[11]

Gustave Duchesne de Bellecourt received the medal of the Légion d'Honneur.[12]

Publications

[edit]- La colonie de Saïgon: les agrandissements de la France dans le Bassin du Mekong [3]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Medzini, Meron. (1971). French Policy in Japan, pp. 20-48., p. 20, at Google Books

- ^ Correspondence relative to the Earl of Elgin's special missions to China Great Britain. Foreign Office p.99 [1]

- ^ Medzini, p. 22., p. 22, at Google Books

- ^ Polak 2001, p.29

- ^ Consuls and the Institutions of Global Capitalism, 1783–1914; by Ferry de Goey, p 75 (2015)

- ^ Satow, p.34-36

- ^ Polak, p.92

- ^ a b Medzini, p. 44., p. 44, at Google Books

- ^ Polak, p.29

- ^ Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States United States. Dept. of State p.491 [2]

- ^ Medzini, p. 47., p. 47, at Google Books

- ^ Base de données Mérimée ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Archived 2008-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Polak, Christian. (2001). Soie et lumières: L'âge d'or des échanges franco-japonais (des origines aux années 1950). Tokyo: Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie Française du Japon, Hachette Fujin Gahōsha (アシェット婦人画報社).

- __________. (2002). 絹と光: 知られざる日仏交流100年の歴史 (江戶時代-1950年代) Kinu to hikariō: shirarezaru Nichi-Futsu kōryū 100-nen no rekishi (Edo jidai-1950-nendai). Tokyo: Ashetto Fujin Gahōsha, 2002. ISBN 978-4-573-06210-8; OCLC 50875162

- Sir Ernest Satow (1921), A Diplomat in Japan, Stone Bridge Classics, ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7

- Medzini, Meron. (1971). French policy in Japan during the closing years of the Tokugawa regime. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674322301; OCLC 161422