Gung Ho (film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

| Gung Ho | |

|---|---|

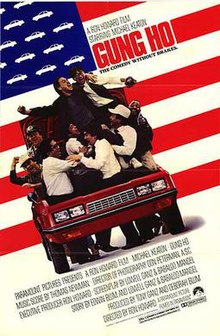

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Howard |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Donald Peterman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $13 million[1] |

| Box office | $36,611,610 |

Gung Ho (released in Australia and New Zealand as Working Class Man)[2] is a 1986 American comedy film directed by Ron Howard and starring Michael Keaton.[3] The story portrays the takeover of an American car plant by a Japanese corporation (although the title phrase is an Americanized Chinese term).

A short-lived TV series based on the film, followed in December 1986.

Plot

[edit]In fictional Hadleyville, Pennsylvania, the local auto plant, which supplied most of the town's jobs, has been closed for nine months. Former foreman Hunt Stevenson goes to Tokyo to try to convince the Assan Motors Corporation to reopen the plant. The Japanese company agrees and, upon their arrival in the U.S., they take advantage of the desperate work force to institute many changes. The workers are not permitted a union, are paid lower wages, are moved around within the factory so that each worker learns every job, and are held to seemingly impossible standards of efficiency and quality. Adding to the strain in the relationship, the Americans find humor in the demand that they do calisthenics as a group each morning and that the Japanese executives eat their lunches with chopsticks and bathe together in the river near the factory. The workers also display a poor work ethic and lackadaisical attitude toward quality control.

The Japanese executive in charge of the plant is Takahara "Kaz" Kazuhiro, who has been a failure in his career thus far because he is too lenient on his workers. When Hunt first meets Kaz in Japan, the latter is being ridiculed by his peers and being required to wear ribbons of shame. He has been given one final chance to redeem himself by making the American plant a success. Intent on becoming the strict manager his superiors expect, he gives Hunt a large promotion on the condition that he work as a liaison between the Japanese management and the American workers, to smooth the transition and convince the workers to obey the new rules. More concerned with keeping his promotion than with the welfare of his fellow workers, Hunt does everything he can to trick the American workers into compliance, but the culture clash becomes too great and he begins to lose control of the men.

In an attempt to solve the problem, Hunt makes a deal with Kaz: if the plant can produce 15,000 cars in one month, thereby making it as productive as the best Japanese auto plant, then the workers will all be given raises and jobs will be created for the remaining unemployed workers in the town. However, if the workers fall even one car short, they will get nothing. When Hunt calls an assembly to tell the workers about the deal, they balk at the idea of making so many cars in so short a time. Under pressure from the crowd, Hunt lies and says that if they make 13,000, they will get a partial raise. After nearly a month of working long hours toward a goal of 13,000—despite Hunt's pleas for them to aim for the full 15,000—the truth is discovered and the workers walk off the job.

At the town's annual 4th of July picnic, Hadleyville mayor Conrad Zwart addresses to the people that Assan Motors plans to abandon the factory again because of the work stoppage, which would mean the end of the town. The mayor threatens to kill Hunt, but Willie, one of the workers, intervenes, insisting that Hunt is not to blame for the closure. Zwart abandons the picnic, even more furious with the townspeople taking Hunt's word over his. Hunt comes clean about the 15,000 car deal. He responds by addressing his observations that the real reason the workers are facing such difficulties is because the Japanese have the work ethic that too many Americans have abandoned. While his audience is not impressed, Hunt, hoping to save the town and atone for his deception, and Kaz, desperate to show his worth to his superiors, go back into the factory the next day and begin to build cars by themselves. Inspired, the workers return and continue to work toward their goal and pursue it with the level of diligence the Japanese managers had encouraged. Just before the final inspection, Hunt and the workers line up a number of incomplete cars in hopes of fooling the executives. The ruse fails when the car that Hunt had supposedly bought for himself falls apart when he attempts to drive it away. The strict CEO is nonetheless impressed by the workers' performance and declares the goal met, calling them a "Good team," to which Kazuhiro replies "Good men."

As the end credits roll, the workers and management have compromised, with the latter agreeing to partially ease up on their requirements and pay the employees better while the workers agree to be more cooperative, such as participating in the morning calisthenics, which are now made more enjoyable with the addition of aerobics class-style American rock music.

Cast

[edit]- Michael Keaton as Hunt Stevenson

- Gedde Watanabe as Takahara "Kaz" Kazihiro, the plant manager

- George Wendt as Buster, a factory worker and Hunt's friend

- John Turturro as Willie, another worker, also Hunt's friend

- Mimi Rogers as Audrey, Hunt's girlfriend

- So Yamamura as Mr. Sakamoto, CEO of Assan Motors

- Sab Shimono as Saito

- Rick Overton as Googie

- Clint Howard as Paul

- Jihmi Kennedy as Junior

- Michelle Johnson as Heather DiStefano

- Rodney Kageyama as Ito

- Rance Howard as Mayor Conrad Zwart

- Patti Yasutake as Umeki Kazihiro (as Patti Yasuiake)

- Jerry Tondo as Kazuo

- Robert Hammond as Auto worker

Both Bill Murray and Eddie Murphy turned down the role of Hunt Stevenson.[4]

Production

[edit]Aside from Pittsburgh and Tokyo, the film was shot at the Sevel Fiat manufacturing plant Argentina, which doubled as the Assan Motors plant. The Fiat Spazio and Regata were used as the Assan cars in the production line.

Music

[edit]The film's score was composed by Thomas Newman and features the songs "Don't Get Me Wrong" by The Pretenders, "Tuff Enuff" by The Fabulous Thunderbirds, "Breakin' the Ice" by Martha Wash, "Working Class Man" by Jimmy Barnes, "Can't Wait Another Minute" by Five Star, and "We're Not Gonna Take It" by Twisted Sister.

Reception

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes the film has a 33% rating based on reviews from 21 critics.[5] On Metacritic it has a score of 48% based on reviews from 9 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[6] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade "B" on scale of A to F.[7]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote: "It's more cheerful than funny, and so insistently ungrudging about Americans and Japanese alike that its satire cuts like a wet sponge."[3] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave it a positive review and wrote: "The film would be funnier and more provocative if it took a stronger stand on one side or the other, but Howard chooses to hedge his bets, selecting an ending that celebrates brotherhood more than the strongly hinted- at notion that American workers would do well to get off their featherbedding backs."[8]

Influence

[edit]Toyota's executives in Japan have used Gung Ho as an example of how not to manage Americans.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ "Gung Ho (1986)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Working Class Man – the movie". National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

Australian poster for the Hollywood comedy-drama Gung Ho (Ron Howard, USA, 1986), released locally as Working Class Man [...].

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (March 14, 1986). "The Screen: 'Gung Ho,' Directed By Ron Howard". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Gray, Beverly (2003). Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon...and Beyond. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 9781418530747.

- ^ "Gung Ho (1986)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Gung Ho". Metacritic.

- ^ "GUNG HO (1986) B". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Gene Siskel (March 17, 1986). "'GUNG HO' SOFTLY SATIRIZES AMERICAN FEATHERBEDDING". ChicagoTribune.com.

- ^ "Why Toyota Is Afraid Of Being Number One". Bloomberg Businessweek. March 5, 2007. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Gung Ho at IMDb

- Gung Ho at AllMovie

- Gung Ho at Box Office Mojo

- Gung Ho on YouTube

- Gung Ho at the TCM Movie Database

- 1986 films

- 1986 comedy films

- 1986 multilingual films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s buddy comedy films

- 1980s English-language films

- American buddy comedy films

- American multilingual films

- Comedy films about Asian Americans

- Films about automobiles

- Films about Japanese Americans

- Films scored by Thomas Newman

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by Ron Howard

- Films set in factories

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films set in Tokyo

- Films shot in Argentina

- Films shot in Pennsylvania

- Films shot in Tokyo

- Films with screenplays by Babaloo Mandel

- Films with screenplays by Lowell Ganz

- 1980s Japanese-language films

- Japan–United States relations

- Japan in non-Japanese culture

- Paramount Pictures films

- English-language buddy comedy films