Guiyi Circuit

Guiyi Circuit Golden Mountain Kingdom of Western Han Dunhuang Kingdom of Western Han 歸義軍 / 西漢金山國 / 西漢敦煌國 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 851–1036 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Circuit/Kingdom/Tributary to Tang dynasty | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Ganzhou (Zhangye) Shazhou (Dunhuang) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Chinese, Old Tibetan, Sogdian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy, Military | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 851 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1036 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||||

The Guiyi Circuit, also known as the Guiyi Army (Chinese: 歸義軍; pinyin: Guīyì Jūn; Wade–Giles: Kui1-i4 Chün1; lit. 'Returning-to-Righteousness Army', 848–1036 AD), Golden Mountain Kingdom of Western Han (西漢金山國; Xīhàn Jīnshān guó; Hsi-han Chin-shan kuo, 909–911), and Dunhuang Kingdom of Western Han (西漢敦煌國; Xīhàn Dūnhuáng guó; Hsi-han Tun-huang kuo, 911–914), was a Chinese regional military command and later an autonomous dynastic regime nominally subordinate to the Tang dynasty, the Five Dynasties, and the Northern Song dynasty. The Guiyi Circuit was controlled by the Zhang family from the second half of the 9th century to the 10th century and then the Cao family until the 11th century. The Guiyi Circuit was headquartered in Shazhou (沙州; modern-day Dunhuang).

Background

[edit]

The Hexi Corridor was an important part of the Silk Road, connecting Central Asia with Northwest China. After the An Lushan Rebellion, the Hexi Corridor was occupied by the Tibetan Empire.[1] Around the 770s or the 780s, Shazhou, otherwise known as Dunhuang, was occupied by the Tibetans.[2]

In respect to their political and social systems, the Tibetans made many changes in Dunhuang according to their own practice. As in many other conquered places, they sent a rtse-rje (Ch. Jieer ) to Dunhuang to be in charge of local administration. Since the Tang institutions in Dunhuang had totally broken down, all of the residents were reorganized into several stong-sdes (literally meaning "thousand households", equal to buluo in Chinese as seen from Dunhuang manuscripts) according to their professions or other standards. It is not very clear yet to what extent the previous social relations and structure were changed, but apparently the great families in Dunhuang remained influential in local affairs during the occupation period. Many members from the Zhang, Yin, Suo, Yan, and other clans were appointed by the Tibetan government to important positions.[3]

— Yang Jidong

Zhang family

[edit]

After some 60 years of Tibetan rule, Tibet entered its Era of Fragmentation and was torn by civil war by 851. Tibetans in the Dunhuang region become part of a group known as wamo in Chinese historical sources.

In 848, Zhang Yichao, a resident of Shazhou, led an uprising and captured Shazhou and Guazhou from the Tibetans.[4]

There are some indications that Zhang Yichao's family was kept away from the political sphere of Dunhuang at that time. The surviving text of the famous stone tablet commemorating Zhang Huaishen's (Zhang Yichao's nephew) merits clearly shows that the property and land of the family were confiscated by the new government shortly after Dunhuang surrendered to the Tibetans. In another manuscript, P 3556, we find that Zhang Yichao's father, Zhang Qianyi, became a xiaoyao zhike ["a free man", a word usually used in traditional China to refer to an intellectual who refused to serve the government and lived in seclusion] and was kept out of political power during the Tibetan period.[5]

— Yang Jidong

By 850 Zhang had captured Ganzhou, Suzhou, and Yizhou.[6] Zhang claimed the title of acting prefect of Shazhou and submitted a petition to Emperor Xuānzong of Tang, offering his loyalty and submission.

In 851 Zhang captured Xizhou (Gaochang). Envoys from Shazhou reached the Tang court and the emperor responded by naming Zhang's territory the Guiyi Circuit and made Zhang Yichao the Guiyi Jiedushi (歸義節度使, Governor of the Guiyi Circuit) and Cao Yijin his secretary general.[6]

In 856 Zhang attacked the Tibetans and defeated them.[7]

The bandits [the Tibetan coalition] had not expected that the Chinese troops would arrive so suddenly and were totally unprepared. Our armies proceeded to line up in a “black-cloud formation,” swiftly striking from all four sides. The barbarian bandits were panic-stricken. Like stars they splintered, north and south. The Chinese armies having gained the advantage, they pursued them, pressing close at their backs. Within fifteen miles, they caught up with them. This is the place where their slain corpses were strewn everywhere across the plain.[7]

— Zhang Yichao Transformation Text

By 861 the Guiyi Circuit had extended its authority to Guazhou, Ganzhou, Suzhou, Yizhou, Lanzhou, Shanzhou, Hezhou, Minzhou, Liangzhou, and Kuozhou.[8]

In 866 Zhang Yichao defeated the Tibetan general bLon Khrom brZhe (Tibetan: བློན་ཁྲོམ་བཞེར་ 論恐熱 Lun Kongre) and seized Luntai (Ürümqi) and Tingzhou. However they were immediately captured by the Kingdom of Qocho afterwards. Xizhou was also captured by the Uyghurs. BLon Khrom brZhe was an attack commissioner in the region. After Langdarma's death in 842, he fought constantly with another commissioner, Shang Bibi.[6] He was captured by Shang Bibi's subordinate, Tuoba Huaiguang, in 866 and sent to the Tang court.[9]

At the same time, the rivalry between the two Tibetan generals, Kongre and Bibi, in the Hexi region worsened in 850. Their troops clashed several times in the eighth and ninth months, and Bibi suffered heavy casualties. The pro-Tang Zhang Yichao seized this opportunity to exert more military pressure on Kongre in 851. Kongre’s followers started to betray him. Desperate to strengthen his position among his dispirited followers, he told them: “I shall pay tributes to the Tang and borrow 500,000 Chinese soldiers to punish those who dare disobey me. I shall then make Weizhou the capital of my state and request Tang to confer on me the title Zanpu.” Kongre came to Chang’an in the fifth month and requested the title Military Commissioner. Emperor Xuanzong, however, had no intention of accepting him as an outer subject. He accorded Kongre an audience but rejected his request. Kongre came back to Weizhou to rally his forces. Many of his former supporters, however, now refused to follow him. With only three hundred companions, Kongre moved farther northwest to Kuozhou and ceased to be a threat to China.[9]

— Wang Zhenping

In 867 Zhang Yichao departed for the Tang court after his brother Yitan, who had been staying in Chang'an as a hostage, died. His nephew Zhang Huaishen succeeded him as Guiyi Jiedushi.[10]

In 869 the Kingdom of Qocho attacked the Guiyi Circuit but was repelled.[11]

In 870 the Kingdom of Qocho attacked the Guiyi Circuit but was repelled.[11]

In 872 Zhang Yichao died at court.[10]

In 876 the Kingdom of Qocho seized Yizhou.[10]

In 867 Zhang Yichao extended his influence to Longyou and Xizhou, when his brother Zhang Yitan 張議潭, who had been sent to the Tang court as a hostage, died in Chang’an. Complying with the order of the court, Zhang Yichao traveled to the court in person. He never returned but eventually died in Chang’an in 872. In his absence, his nephew Zhang Huaishen 張淮深 took over the rule of the Guiyijun, yet the Tang court did not officially appoint him military commissioner. Thus while Zhang Huaishen received no support from the Tang, the Uighurs, as part of their westward expansion, deeply invaded the territories of Ganzhou and Suzhou, and even attacked Guazhou. Even though Zhang Huaishen successfully defeated their scattered attacks, in 876 the Xizhou Uighurs seized Yizhou and with this the Guiyijun lost one of its important garrisons.[10]

— Rong Xinjiang

In 880, Qocho attacked Shazhou, but was repelled.[12]

Around the years 881 and 882, Ganzhou and Liangzhou slipped from the control of the Guiyi Circuit. The Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom would establish itself in Ganzhou by 894.[11] In Liangzhou, the Tibetan state of Xiliangfu established itself by 906.[13]

In another memorial presented to the Emperor Tang Yizong, Zhang Yichao implored the court not to abandon Liangzhou. It seems that the Wamo and Tibetans were trying hard to recapture Liangzhou in the late 860s, and their attacks appear to have been very heavy so that Chang'an was planning to withdraw from Liangzhou. Apparently, weak Tang could not give the Returning to Righteousness Army any practical help.[14]

— Yang Jidong

In 890 Zhang Huaishen was assassinated and his cousin Zhang Huaiding succeeded him.[15]

In 892 Zhang Huaiding died and left his son in the care of Suo Xun (索勳), son-in-law of Zhang Yichao. Suo Xun declared himself Guiyi Jiedushi.[15]

In 894 Suo Xun was killed by a local aristocrat by the name of Li Mingzhen and Zhang Yichao's daughter. Li's sons shared control of Guiyi Circuit afterwards.[15]

In 896 Li Mingzhen's sons were ousted and Zhang Chengfeng (張承奉), a grandson of Zhang Yichao, became jiedushi.[15]

In 904, Zhang Chengfeng attacked Qocho and seized Yizhou (Hami) and Xizhou (Gaochang).[16]

In 910 Zhang Chengfeng received news of the Tang dynasty's demise and declared himself Emperor Baiyi. The Guiyi Circuit was renamed Kingdom of Jinshan.[17]

Kingdom of Jinshan

[edit]The rulers of Guiyi in Dunhuang briefly called themselves "emperors" for a short period after the final collapse of the Tang dynasty.[18]

In 910 Zhang Chengfeng established a kingdom known as the Xihan Jinshan (西漢金山國 Xīhàn Jīnshānguó), "The Golden Mountain Kingdom of the Western Han," and gave himself the title of "Son of Heaven."[19][20] This was followed by an invasion by the Ganzhou Uyghurs.

In 911 the Ganzhou Uyghurs attacked again and the Kingdom of Jinshan was forced to become a lesser partner in an alliance with the Ganzhou Uyghurs. The Great Chancellor (大宰相) and the elders of Jinshan State made a treaty with the Ganzhou Uyghurs, recognizing their superiority. The relationship between the two was prescribed as

"...the Khan is the father, and the Son of Heaven is the son..." (...可汗是父,天子是子...)[19]

In 914 Cao Yijin usurped the throne and abolished the kingdom, reverting the name to Guiyi Army.

During the Zhang family’s rule, the Guiyijun basically controlled the entire Hexi region but by the end of the 10th century it was only able to keep the prefectures of Guazhou and Shazhou. During the Cao family’s rule which began in 914, the Guiyijun maintained friendly relations with the Xizhou Uighurs in the west and the kingdom of Khotan. With Khotan they even entered into a marriage alliance, as the Khotanese king Li Shengtian 李聖天 married the daughter of Cao Yijin, and Cao Yanlu also married the third daughter of the king of Khotan. Hence there were very close contacts between the two states. We can even say that in the eyes of the Khotanese people the Hexi-based Guiyijun came to represent China proper. During the late 10th century, as a result of the holy war launched by the Islamic Karakhanid Khanate against Khotanese Buddhists, Khotan increasingly relied on its eastern neighbors to resist hostile invasion.[21]

— Rong Xinjiang

Cao family

[edit]

In 914 Cao Yijin (曹議金) usurped the throne and restored the name Guiyi Circuit.[22]

In 914, Cao Yijin 曹議金 (also called Cao Rengui 曹仁貴) took over the throne from Zhang Chengfeng, abolished the Jinshan state and the title of king, calling himself once again military commissioner of the Guiyijun. Cao Yijin improved the relationship with neighboring peoples, sent envoys to Ganzhou and married the daughter of the Uighur Khagan, thus reinforcing a positive relationship with the Uighurs. In 918 Cao Yijin, with the support of the Uighur Khagan, the puye 僕射 of Liangzhou and the xianggong 相公 of Lingzhou, sent envoys to the Later Liang and was conferred by the court the title of military commissioner of the Guiyijun. Cao Yijin constructed a large cave (Cave 98) at Mogao in celebration of being acknowledged by the central dynasty. He strengthened his rear by sending envoys to the Yizhou and Xizhou Uighurs, and in 925, took advantage of the change of khagans among the Ganzhou Uighurs and led a military campaign against them, defeating them after heavy fighting. The newly established khagan took Cao Yijin’s daughter as his wife and thus became the military commissioner’s son-in-law.[17]

— Rong Xinjiang

In 916 Cao Yijin married a Ganzhou Uyghur princess and sent delegations to the Later Liang.[23]

In 924 the Ganzhou Uyghur Khagan died and his successors Renmei and Diyin declared war on each other, with Diyin coming out victorious.[22]

In 925 Cao Yijin defeated the Ganzhou Uyghurs.[22]

In 926, Diyin died, and Aduoyu (阿咄欲) became the Khan of the Ganzhou Uyghurs. Aduoyu married a daughter of Cao Yijin.[22]

Kingdom of Guiyi

[edit]In 931 Cao Yijin declared himself as Lord (令公) and Great King-reclaiming-the-west (拓西大王).[17][24] The Cao rulers continued using the Chinese reign era names, and maintained cordial relations with the Chinese heartland and its socio-political system.[25]

In 934 Cao Yijin married his daughter to the king of Khotan.

The Cao family of Dunhuang and the royal family of Khotan had close ties. The Khotanese king Visa Sambhava, who ruled Khotan from 912 to 966, also used the Chinese name Li Shengtian. Sometime before 936 he married the daughter of Cao Yijin. The Khotanese royal family maintained a residence in Dunhuang where Visa Sambhava’s wife often stayed and where the heir to the Khotanese throne lived. The crown prince’s residence functioned as a representative office for the Khotanese, and it is very possible that the Khotanese language documents found in cave 17 were an archive donated by the crown prince’s residence to the Three Realms Monastery.[26]

— Valerie Hansen

In 935 Cao Yijin died and was succeeded by his son, Cao Yuande.[27]

In 939 Cao Yuande (曹元德) died and was succeeded by his brother Yuanshen (曹元深).[27]

In 944 Cao Yuanshen died and his brother Yuanzhong (曹元忠) succeeded him. Cao Yuanzhong's reign was characterized by progress in agriculture, transportation, and printing.[28] Relationship with the Ganzhou Uyghurs remained relatively stable during this period.[29]

In 950 the first depiction of fire lances appeared in Shazhou.

In 974 Cao Yuanzhong died and his nephew Cao Yangong (曹延恭) succeeded him.[30]

In 976 Cao Yangong died and his brother Yanlu (曹延祿) succeeded him. Yanlu married a Khotanese princess.[31]

During the Cao family’s rule of the Guiyijun in the Five Dynasties and early Song periods, the Yulin caves were also frequently visited by members of the Cao family, as it is attested by the many surviving donor images. For example, in Cave 16 the “Lady Li from Longxi 隴西, Princess Shengtian 聖天公主 of the Northern Uighurs” is the Uighur wife of Cao Yijin 曹議金. Donor figures and inscriptions of Guiyijun military commissioners Cao Yuande 曹元德, Cao Yuanzhong or Cao Yanlu can also be found in the Yulin caves.[32]

— Rong Xinjiang

In 1002 Cao Yanlu's nephew Cao Zongshou rebelled in Shazhou. Cao Yanlu and his brother Cao Yanrui (曹延瑞) committed suicide. Cao Zongshou became ruler of Guiyi.[33][34]

In 1014 Cao Zongshou died and his son Cao Xianshun (曹賢順) succeeded him.[35]

In 1028 the Tanguts defeated the Ganzhou Uyghurs.[36]

In 1030 Cao Xianshun surrendered to the Tanguts.[36]

In 1036 the Tanguts, who later established the Western Xia, annexed the Kingdom of Guiyi.[36]

Religion

[edit]

Buddhism was prevalent in Dunhuang (Shazhou) during the Guiyi period, and had been before as well under Tibetan rule. Under Tibetan rule, the number of Buddhist temples increased from 6 to 19 and more than 40 new caves were created. Confucian classics were also taught in Buddhist monasteries.[3] Many of Zhang Yichao's family converted to Buddhism. He also studied Buddhism in his youth. A manuscript from Dunhuang contains a signature that reads, "written by Buddha's secular disciple Zhang Yichao."[38] After Zhang Yichao took over, the Buddhists of Dunhuang reconnected with the Tang court and he presented the work of Cheng'en, a monk from the Hexi Corridor, to the Tang court to support the Buddhist restoration movement of emperors Xuanzong and Yizong. Texts that had been lost in Dunhuang due to warfare were reproduced using Tang copies.[39] Despite Zhang's association with Buddhism, due to a shortage of manpower, he made many temple households independent peasants to satisfy the demands of recruitment.[40]

As the Tang dynasty collapsed and entered the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, Buddhism in Dunghuang gravitated towards lay Buddhism and apocryphal sūtras rather than scripture-based tradition. At the beginning of the Guiyi period, the Buddhist master Faheng and his disciples Fajing and Fahai delivered lectures in Dunhuang. After 883, lectures by monks are no longer mentioned in manuscript colophons and only lay devotional practices such as building caves, erecting statues, and addresses to common people are recorded.[39]

In addition to Buddhism, discoveries of Manichaean, Nestorian Christian, and Zoroastrian documents and other artifacts at Mogao Caves dating back to the Guiyi era reveal their coexistence in a multi-religious world.[41]

Sogdians of Dunhuang

[edit]

During the Tang and subsequent Five Dynasties and Song dynasty, large communities of Sogdians lived in China, especially in the multicultural entrepôt of Dunhuang, Gansu, a major center of Buddhist learning and home to the Buddhist Mogao Caves.[42] While the region occasionally fell under the rule of different states (the Tang, the Tibetan Empire, and later the Western Xia led by the Tanguts), it retained its multilingual nature as evidenced by an abundance of manuscripts (religious and secular) in Chinese and Tibetan, but also Sogdian, Khotanese (another Eastern Iranian language native to the region), Uyghur, and Sanskrit.[43]

To the east of the Returning to Righteousness Army alone, names of some ten ethnic groups appear in both Chinese literature and Dunhuang manuscripts. Some of them had never been seen before in previous histories, such as the Wamo, the offsprings of the Chinese residents who were totally assimilated to the Tibetans during the century of Tibetan rule, and the Tokharian Longjia who came from Agni (Karashahr) and settled in many oases in the Gansu Corridor.[40]

— Yang Jidong

From the Chinese surnames listed in the Tang-era Dunhuang manuscript Pelliot chinois 3319V (containing the following text: 石定信右全石丑子石定奴福延福全保昌張丑子李千子李定信), the names of the Nine Zhaowu Clans (昭武九姓), the prominent ethnic Sogdian families of China, have been deduced.[44] Of these the most common Sogdian surname throughout China was Shi (i.e. 石), whereas the surnames Shi (i.e. 史), An, Mi (i.e. 米), Kang, Cao, and He appear frequently in Dunhuang manuscripts and registers.[45] Zhang Yichao appointed An Jingmin as vice commissioner of Guiyi, Kang Shijun as prefect of Guazhou, and Kang Tongxin as magistrate of some towns to the east.[46] The influence of Sinicized and multilingual Sogdians during this Guiyijun (歸義軍) period (c. 850 - c. 1000 AD) of Dunhuang is evident in a large number of manuscripts written in Chinese characters from left to right instead of vertically, mirroring the direction of how the Sogdian alphabet is read.[47] Sogdians of Dunhuang also commonly formed and joined lay associations among their local communities, convening at Sogdian-owned taverns in scheduled meetings mentioned in their epistolary letters.[48]

From the beginning of Tibetan rule over Dunhuang (786) through the Guiyijun period (848–1036), descendants of Sogdians were still active in Dunhuang. Zheng Binglin 鄭炳林 has published in succession a series of articles on the Sogdians in the Guiyijun, and on manuscripts written by Sogdians. Although these articles provide a detailed analysis of Sogdians in Dunhuang during this period, it is still questionable whether the sources he utilized indeed refer to Sogdians. Because of the continuous presence of Sogdians in Dunhuang and the substantial influence of Sogdian culture, I have raised the possibility that the Cao family who ruled Dunhuang during part of the Guiyijun period may have also been Sogdian descendants.[49]

— Rong Xinjiang

Mogao Caves

[edit]-

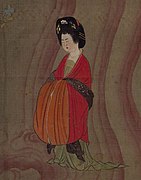

Dunhuang woman in Tang dress

-

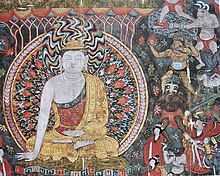

Dunhuang Buddhist woman

-

Lady Liangguo, a Buddhist donor

-

Buddhist donor and her retinue, 983 AD

-

Dunhuang Buddhist donor

-

Khotanese donors

-

Dunhuang Buddhist women

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "补唐书张议潮传" by 罗振玉

- ^ "吐蕃和平占領沙州城的宗教因素" by 張延清

- ^ a b Yang 1998, p. 101.

- ^ Maṇḍalas in the Making: The Visual Culture of Esoteric Buddhism at Dunhuang. BRILL. December 18, 2017. ISBN 9789004360402.

- ^ Yang 1998, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Rong 2013, p. 40.

- ^ a b Hansen 2015, p. 188.

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 41.

- ^ a b Wang 2013, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d Rong 2013, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Russell-Smith 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Baumer 2012, p. 314.

- ^ Ryavec 2015, p. 83.

- ^ Yang 1998, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Rong 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Baumer 2012, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Rong 2013, p. 44.

- ^ Xin Wen (2023). The King's Road: Diplomacy and the Remaking of the Silk Road. Princeton University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780691237831.

- ^ a b "归义军史研究——唐宋时代敦煌历史考索" by 荣新江

- ^ "羅叔言《補唐書張議潮傳》補正" by 向達

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 327-8.

- ^ a b c d Russell-Smith 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie. Abhinav Publications. 1994. ISBN 9788170173137.

- ^ Lilla Russell-Smith (2021). Uygur Patronage in Dunhuang: Regional Art Centres on the Northern Silk Road in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. BRILL. p. 64. ISBN 9789047415695.

- ^ Wenjie Duan (1994). Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie. Abhinav Publications. p. 189. ISBN 9788170173137.

- ^ Hansen 2015, p. 222.

- ^ a b Russell-Smith 2005, p. 64.

- ^ "中国古代印刷史" by 罗树宝

- ^ "敦煌历史上的曹元忠时代" by 荣新江

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 23, 65.

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 477.

- ^ "宋会要辑稿" by 徐松

- ^ "续资治通鉴长编" by 李焘

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 46.

- ^ a b c "西夏紀" by 戴锡章

- ^ "The Genius of China", Robert Temple

- ^ Yang 1998, p. 108.

- ^ a b Rong 2013, p. 346-7.

- ^ a b Yang 1998, p. 124.

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 73–5.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 870-71.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, p 871.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 871-72.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, p. 872.

- ^ Yang 1998, p. 121.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 870, 873.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 872-73.

- ^ Rong 2013, p. 331.

Bibliography

[edit]- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Baumer, Christoph (2012), The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century - Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Hansen, Valerie (2015), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 - The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 9780521243049

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744–840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004252332, ISBN 9789004250420

- Russell-Smith, Lilla (2005), Uygur Patronage in Dunhuang

- Ryavec, Karl E. (2015), A Historical Atlas of Tibet

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yang, Jidong (1998), Zhang Yichao and Dunhuang in the 9th Century