Guayaquil Conference

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2011) |

| History of Ecuador |

|---|

|

|

|

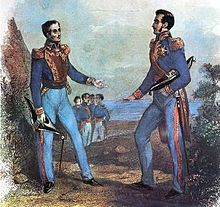

The Guayaquil Conference (Spanish: Conferencia de Guayaquil) was a meeting that took place on July 26–27, 1822 in the port city of Guayaquil (today part of Ecuador) between libertadors José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar to discuss the future of Peru, and South America in general. The conference is considered a turning point in the South American independence process.[1]

Lima, a major royalist stronghold, had been captured by San Martín, who declared Peru's independence. Meanwhile, Bolívar had a successful campaign in Venezuela and New Granada, forming Gran Colombia. In Ecuador, a revolt in Guayaquil sparked independence movements, raising questions about its future alignment. Despite their common goals, Bolívar and San Martín could not agree on governance strategies for the liberated nations, with Bolívar favoring republics and San Martín supporting constitutional monarchies. Post-conference, San Martín retired, and Bolívar continued the liberation efforts.

Causes

[edit]Lima, capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, was the most important city of the Spanish colonies in South America. It was a royalist stronghold during the Spanish American wars of independence, fighting against the several independentist outbreaks. For this reason, after the conclusion of the Chilean War of Independence the general José de San Martín organized a navy that allowed his forces to siege and capture the city, declaring the independence of Peru shortly afterwards. However, there was still a strong royalist force in the Peruvian countryside.

Simón Bolívar led another independentist campaign. He liberated Venezuela after many attempts and with the help of Francisco de Paula Santander liberated the United Provinces of New Granada, creating the Gran Colombia. The battles of Lake Maracaibo secured the independence of Venezuela.

A revolt in Guayaquil proclaimed the independence of the city, followed by other Ecuatorian cities. Neither San Martín nor Bolívar took part in the initial development of the Ecuadorian War of Independence. The Ecuadorians discussed the future of the region: some factions wanted to join Colombia, others to join Peru, and others to become a new nation. Bolívar ended the discussion by annexing Guayaquil into Colombia. There was Peruvian pressure on San Martín to do a similar thing, to annex Guayaquil to Peru.

Topics

[edit]The main objective was to define how the war of independence would end, given that the royalists were reorganizing. And what should happen to the newly independent countries to ensure and consolidate South American independence. This taking into account that the liberating campaigns had different ways of being carried out by each of their leaders, being in the case of Gran Colombia a war declared to the death against the royalists, which did not accept ambiguities.

Another objective was to deal with sovereignty over the Free Province of Guayaquil, whose capital, Guayaquil, being part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, was liberated from Spanish rule in 1820 thanks to the uprising of the city's garrison, formed by the so-called “Cuzco Reserve Grenadiers” regiment, made up of Peruvian royalists originally from Cuzco and having declared themselves independent, that showed strong ties with Peru.

San Martín arrived in Guayaquil on July 25, where he was enthusiastically greeted by Bolívar. However, the two men could not come to an agreement, despite their common goals and mutual respect, even when San Martín offered to serve under Bolívar. Both men had very different ideas about how to organize the governments of the countries that they had liberated. Bolívar was in favor of forming a series of republics in the newly independent nations based on his own modifications to the political theory underlying the Constitution of the United States, whereas San Martín preferred European and particularly British models of constitutional rule, hoping to build the liberated nations of South America as constitutional monarchies. San Martín was also in favor of placing a European prince in power as King of Peru when it was to be liberated.

Consequences

[edit]San Martín, after meeting with Bolívar for several hours on July 27, stayed for a banquet and ball given in his honor. Bolívar proposed a toast to “the two greatest men in South America: the general San Martín and myself” (Por los dos hombres más grandes de la América del Sur: el general San Martín y yo), whereas San Martín drank to “the prompt conclusion of the war, the organization of the different Republics of the continent and the health of the Liberator of Colombia (Por la pronta conclusión de la guerra; por la organización de las diferentes Repúblicas del continente y por la salud del Libertador de Colombia).[2][3]

After the conference, San Martín went to Lima and abdicated his powers in Peru in front of the newly formed Peruvian Congress and returned to Argentina. Soon afterward, he left South America entirely and retired in France.

Legacy

[edit]The Guayaquil conference inspired a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, Guayaquil, published in his book El informe de Brodie (1971), in which he explores the possible psychological relation between San Martín and Bolívar.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pérez Valdivia, Javier; Puerta Villagaray, César; Morán, Daniel; Pérez Valdivia, Javier; Puerta Villagaray, César; Morán, Daniel (September 2021). "Two suns cannot shine under the same sky". The interview of Guayaquil between José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar (1822)". Desde el Sur. 13 (3). doi:10.21142/des-1303-2021-0029. S2CID 245626062.

- ^ "Jose de San Martin". Archived from the original on 2007-03-04. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Biografía del Libertador José de San Martín

- ^ "Acts of narration". TLS. January 18, 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

Bibliography

[edit]- Galasso, Norberto (2000). Seamos libres y lo demás no importa nada [Let us be free and nothing else matters] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Colihue. ISBN 978-950-581-779-5.

- Lecuna, Vincente (1951). "Bolívar and San Martín at Guayaquil". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 31 (3): 369–393. doi:10.2307/2509398. JSTOR 2509398.

- Masur, Gehard (1951). "The Conference of Guayaquil". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 31 (2): 189–229. doi:10.2307/2509029. JSTOR 2509029. S2CID 222572159.