Grenoble-Bastille cable car

| Grenoble-Bastille cable car | |

|---|---|

The top end of the cable car | |

| Overview | |

| Location | Grenoble |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 45°11′35″N 5°43′34″E / 45.19306°N 5.72611°E |

| Open | September 1934 |

| Website | www |

| Operation | |

| Operator | City of Grenoble |

| No. of carriers | 3 x 2 (winter) 4 x 2 (summer) |

| Carrier capacity | 18 x 2 (w) or 24 x 2 (s) |

| Operating times | 9 am - 12 am |

| Trip duration | 3.5 minutes |

| Technical features | |

| Aerial lift type | Bi-cable gondola fixed grip pulsed |

| Manufactured by | Poma |

| Line length | 2,310 feet (700 m) |

| Vertical Interval | 872 feet (266 m) |

The Grenoble-Bastille cable car (French: Téléphérique de Grenoble Bastille), also affectionately known as Les bulles (English: the bubbles), is a cable car in the French city of Grenoble. It links the city centre with the Bastille, a former fortress overlooking the city.[1]

In July 2017, the metropolis of Grenoble installed a webcam on the roof of the upper station of the cable car, offering Internet users a 220° panoramic photograph of the city every 20 minutes, with several definitions of images. Thanks to the archiving of these photographs that have been available since July 13, 2017, visitors to the terrace of the Geologists and the belvedere Vauban can see each other in the photos.[2]

History

[edit]The line was inaugurated on 29 September 1934.[3] In 1934 cable cars were no longer an innovation. The cable car at the Aiguille du Midi had been in existence for ten years, and the one at Salève for two; by that time Europe had a sizeable number. Even in Grenoble, a cable transportation system existed between Mount Jalla and the area of Porte de France since 1875, used to transport limestone from the quarries to the cement industry. [citation needed]

In Grenoble, the desire for openness and expansion of the city led its mayor at the time, Paul Mistral, to successfully organize the Exposition internationale de la houille blanche (International exposition of hydropower also known as "white coal") in 1925, and subsequently to acquire land for the city's future airport. In 1930, together with the vice-chairman of the chamber of tourism, Paul Michoud, he planned the world's first urban cable car in the city. The site of the Bastille overlooking the Grenoble area was naturally chosen to become a tourist attraction.[4] The site, fortified a century earlier by General Haxo, had a natural promontory offering a 360° panoramic view.

Stations

[edit]

The architect, Jean Benoit, designed the stations. The work was entrusted to the Franco-German consortium Bleichert, Neyret-Beylié, Para and Milliat. The choice of the location for the upper station was not a problem; it had to be close to the barracks of the dungeon, which was transformed into a restaurant. The site of the lower station was between the Jardin des dauphins and the Jardin de ville. It was finally decided that the lower station would be placed near the Jardin de ville, on the banks of the Isère. Its architectural design took elements of the Tour de l'Isle on the opposite bank, and a covered bridge was constructed across the road. In 1959, a circular extension was added to the lower station, and was used as a waiting room with a capacity of one hundred people.[5]

By 1975 it had fallen behind building standards, and its ageing equipment and falling attendance convinced the municipality of Grenoble to demolish the lower station and rebuild it. The cables of 1967 were however preserved. The local architectural firm Groupe 6 was mandated for the design. The wiring and cabins were entrusted to Poma, and inaugurated under a year later in September 1976. The new station was built with big glass windows, like the new cabins, and on the other side of the road. A central pillar containing the engine is topped by a steel frame and cube-shaped glass.[6]

For its part, the upper station was not changed, but was rearranged to receive the new continuously rotating mechanisms, the two huge 46-tons counterweights of the supporting cables, and finally the 24-ton counterweight of traction cable.

In September 2005, access was provided for the disabled, enabling them to use the cable car; the fort itself had new elevators installed for the same reason.

Cabins

[edit]

At its inception in 1934, the cable-car used two blue dodecagonal (12-sided) cabins, with a capacity of 15 persons each, including operator. The cabins were made by the German firm Bleichert, and operated on the principle of back and forth: one rose while the other descended, each on independent cables.

In March 1951, the two cabins were replaced by green ones, which were soon thereafter repainted in yellow and red, the colours of the city. The cabins were glass boxes with rounded corners accommodating 21 people, manufactured by the coach company of Henri Crouzier in Moulins, Allier. They became high-profile attractions with the advent of colour postcards during the 1968 Winter Olympics.[7]

In July 1976,[7] after several months of interruption caused by the construction of a new lower station, new spherical cabins with windows manufactured by the local company Poma were installed. They were quickly dubbed the "bubbles". Each bubble could accommodate up to 6 people. There were initially 3 in number, increased to 4 in winter and 5 in summer (and, as at 2017, two sets of 5). The cable car became pulse-driven: it moved in a continuous rotary motion, although slowed while at the stations.

The inauguration of the bubbles on 18 September 1976 attracted much more attention from the media than imagined by the initiators of the cable car. Around 16:00, a derailment occurred at the lower station, just above the Isère, making the radio and television news at 20:00, and a huge crowd gathered along the banks of the river to help with the rescue. Civil protection helicopters worked in relays to free the occupants. The rescue ended at 20:45 without damage. This event is fortunately the only such incident in the history of this cable car; since then safety standards have improved. Inspections of equipment are made with different frequencies and each year in January the cable car is closed for twenty days to perform safety checks and drills.

Figures

[edit]- Passengers per year: 306,151 in 2014;[8] 315,074 in 2015

- Vertical drop: 263 m (863 ft)

- Altitudes 216 m (708 ft) to 482 m (1,581 ft)

- length on the slope: 685 m (2,246 ft)

- Speed: 0 to 6 m/s (20 ft/s)

- Travel time: varies between 3 and 4 minutes

- 1 tower of 23.5 m (77 ft), located two thirds of the way from the bottom

- Engine: 164 kW (220 hp); 1,600 rpm

- opened 4,000 hours per year (average French ski lifts: 1,200 hours)

- Attendance: 277,000 users in 2008, 325,000 users in 2011[9]

Panoramic images

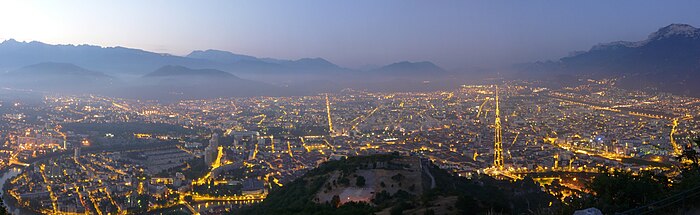

[edit]In the foreground is the Isère river, and behind that the Drac river. The straight avenue is the 8 km-long Cours Jean Jaurès, which finishes at the Place Hubert Dubedout. In the background are the Vercors mountains, and in front of the Isère the Chartreuse mountains (to which the Bastille belongs).

References

[edit]- ^ "The cable car: Introduction". bastille-grenoble.com. Archived from the original on 2009-09-06. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Website of Grenoble Metropole.

- ^ (in French) Revue de géographie alpine, Jacqueline Chamarier, le téléphérique de la Bastille a vingt ans, volume 42.

- ^ "Introduction Out of the ordinary…". bastille-grenoble.com. Archived from the original on 2009-09-06. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ (in French) History of Grenoble-Bastille cable car Archived 2016-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The history of Grenoble-Bastille's cable-car". bastille-grenoble.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ^ a b (in French) france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr September 2014, Téléphérique de la Bastille, 80 ans de bulles entre ville et montagne à Grenoble

- ^ (in French) Activity report (2014), page 5. Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ According to Le Dauphiné Libéré, January 3, 2012.

Works cited

[edit]- La Bastille de Grenoble et son téléphérique, Marc Fénolli and Béatrice Méténier, Éditeurs Les affiches de Grenoble et du dauphiné et la régie du téléphérique, September 2006, ISBN 2-9527460-0-1

External links

[edit]- Official website (in French)