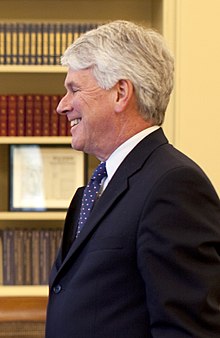

Gregory B. Craig

Gregory B. Craig | |

|---|---|

| |

| White House Counsel | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – January 3, 2010 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Fred Fielding |

| Succeeded by | Bob Bauer |

| 19th Director of Policy Planning | |

| In office July 10, 1997 – September 16, 1998 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Jim Steinberg |

| Succeeded by | Morton Halperin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gregory Bestor Craig March 4, 1945 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) Emmanuel College, Cambridge (MPhil) Yale University (JD) |

Gregory Bestor Craig (born March 4, 1945) is an American lawyer and former White House Counsel under President Barack Obama, from 2009 to 2010. A former attorney at the Washington, D.C. law firm of Williams & Connolly, Craig has represented numerous high-profile clients. Prior to becoming White House Counsel, he served as assistant to the President and special counsel in the White House of President Bill Clinton, where he directed the team defending Clinton against impeachment. Craig also served as a senior advisor to Senator Edward Kennedy and to Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

After leaving the Obama administration, Craig returned to private practice as a partner at the law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. In 2019, Craig was indicted on charges of lying to federal prosecutors about the work he did at Skadden on behalf of the government of Ukraine under Viktor F. Yanukovych, work referred to Craig by Paul Manafort, then a Yanukovych consultant. Craig was acquitted in a jury trial.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Craig was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 4, 1945.[2] Craig's father, William Gregory Craig (1914–2005), was a Navy officer who served in World War II and after the war served as chancellor of the Vermont State Colleges system (1973–1976), chancellor of the California Community College system (1977–1980), and president of the Monterey Institute (1980–1988).[3] The elder Craig unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination for Governor of Vermont.[3] The younger considers Vermont his home state;[2] he grew up as one of four boys in Middlebury, Vermont.[4] He spent some of his early years in Palo Alto, California.[5]

Craig attended Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.[5][6] He then attended Harvard University, graduating with an A.B. in 1967.[5][6][7] At Harvard, Craig sang with the Krokodiloes, Harvard's oldest all-male a cappella group.[6][8] Craig graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a concentration in history.[6] His senior thesis was on Upton Sinclair's campaigns during the Great Depression.[6] Craig was elected chairman of the Harvard Undergraduate Council during his senior year.[6] During his time at Harvard, Craig became familiar with prominent faculty members, including Henry Kissinger.[6] During this period, Craig registered black voters in Mississippi, tutored children in Harlem, and "became Harvard's most widely quoted student leader in opposition to the Vietnam War."[9]

Craig considered claiming conscientious objector status to avoid the Vietnam-era draft, but he eventually submitted himself to the Exeter, New Hampshire, draft board, saying that "I thought it was the only honorable thing to do."[9] Craig received a medical deferment for a shoulder injury.[5][9] Craig earned a Lionel de Jersey Harvard Fellowship to study at Cambridge University in England,[6] where he received a master's degree in historical studies in 1968.[5][7]

After returning to United States, Craig attended Yale Law School, where he was a member of the same class as Bill Clinton, Hillary Rodham, and David E. Kendall.[5] In the fall of 1971, Craig sublet his apartment in New Haven to Rodham and Clinton for $75 a month.[4] Craig received his J.D. degree from Yale Law School in 1972.[7][10] After graduating, Craig, along with Kendall, took a job at the law firm of Williams & Connolly.[5][10]

Legal and government career from 1972 to 2009

[edit]Craig worked mostly at Williams & Connolly from 1972 to 2009, with his tenure there interrupted by periods working as a public defender, on the staff of Senator Edward M. Kennedy, at the State Department, and at the Clinton White House.[5]

Three years after Craig began at Williams & Connolly, he left to follow his wife to Connecticut, where she obtained a master's degree in fine arts.[5] While in Connecticut, Craig worked as a public defender.[5]

Craig later returned to Williams & Connolly, where he was protege of Joe Califano and Edward Bennett Williams.[9] One of Craig's first big criminal cases at Williams & Connolly was that of multimillionaire D.C. developer Dominic F. Antonelli Jr., the chairman of Parking Management Inc. (PMI), who was charged with bribery and conspiracy in connection with an attempt to secure a D.C. government lease from D.C. official Joseph P. Yeldell, his codefendant. Craig defended Antonelli alongside his Williams & Connolly colleagues Kendall and Williams.[5][11][12] Antonelli and Yeldell were convicted by a jury in Washington, but that conviction was vacated on grounds of jury bias, and at a retrial in Philadelphia the two men were acquitted.[12][13] Craig is an admirer of Edward Bennett Williams, saying that he was "the great lawyer of our generation."[14]

In 1981, Craig was a member of the team that represented John W. Hinckley, Jr., who attempted to assassinate Ronald Reagan; Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity.[2][7] Craig worked in the office of Senator Edward M. Kennedy as his chief defense, national security, and foreign policy aide from 1984 to 1988.[2][7] Craig also defended Kennedy's nephew William Kennedy Smith on charges of assault; William Kennedy Smith had earlier been acquitted on rape charges in 1991.[2]

Craig also served as chairman of the International Human Rights Law Group (later Global Rights).[15]

In 1996, Craig was offered the post of White House Counsel by Bill Clinton, but Craig declined.[16] Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright appointed Craig to the post of Director of Policy Planning at the State Department in 1997.[2][7] Craig served in that post from June 1997 to 1998.[7][15] As policy planning director, Craig served as a senior advisor to Albright[15] and led the State Department's internal think tank.[14] In October 1997, Albright gave Craig the additional post of Special Coordinator for Tibetan Affairs, in order "to focus attention on China's suppression of Tibet's cultural and religious traditions."[15]

Craig worked in the White House during the Clinton administration from 1998 to 1999, holding the title of Assistant to the President and special counsel.[7] Craig's old friend and law partner Kendall was Clinton's personal attorney.[9] Craig was brought on specifically to coordinate the White House's defense of Clinton during impeachment proceedings against him. Termed the "quarterback" by Clinton, Craig worked from the West Wing and oversaw legal, political, congressional, and public relations aspects of the defense, reporting regularly to Clinton and consulting with John Podesta, the White House chief of staff.[9] However, Craig claimed in an interview with PBS Frontline in July 2000 that Podesta was the one who recruited him and that Podesta told him that the White House needed a "coordinator quarterback."[17] He also stated that he mainly coordinated with Podesta and that "I could name to John ten other lawyers in America that could do the job as well, if not better."[17] Craig also stated that he wanted to remain in the State Department and that when Podesta first asked him to be the lawyer, he told him "Forgive me, John, if I'm not enthusiastic about the idea."[17]

Craig's style was collegial in nature and he earned the respect of other White House staffers, although there was tension with then-White House Counsel Charles Ruff; according to The Washington Post, "each man behaved as if he were the one in charge" and the two had different professional styles.[9] Ruff, Kendall, and Craig were three members of a five-member team of lawyers defending the president; the other two were Cheryl D. Mills and Dale Bumpers.[18]

Craig then returned to private practice at Williams & Connolly as a partner.[19] During the Elián González affair in 2000, Craig represented Juan Miguel Gonzáles, the Cuban father of six-year-old Elián González, in an international child custody dispute involving "the volatile field of Cuban-American relations" which ended with the boy's return to Cuba.[2][7][20]

Other high-profile clients represented by Craig while at Williams & Connolly include Richard Helms, the ex-director of Central Intelligence who was convicted of lying to Congress over the CIA's role in removing Salvador Allende;[14] UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan;[14][21] Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn;[21] and Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega.[14] He reported earning a salary of $1.7 million from the firm in 2008.[19]

Obama presidential campaign

[edit]Craig met Barack and Michelle Obama for the first time in 2003, at the home of Vernon Jordan, a close friend of the Clintons, and the then-Illinois state senator impressed Craig.[4][22] Despite close ties to the Clintons, Craig urged Obama to run for president, and became an informal foreign policy adviser to him.[23] In March 2007, Craig publicly declared his support for Obama in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary; because of his close ties to the Clintons, this attracted widespread attention.[4][24]

In summer 2008, during the presidential campaign, Obama decided to support legislation (specifically, an amendment to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act) for granting legal immunity to telecommunications companies that cooperated with the Bush administration's warrantless NSA wiretapping program.[25] This angered many Democrats, because it was a reversal of Obama's earlier vow during the primary campaign to oppose such legislation and to filibuster against it.[25] In his role as an advisor to the Obama campaign, Craig defended Obama's reversal, and said that Obama "concluded that with FISA expiring, that it was better to get a compromise than letting the law expire."[25] This was incorrect, as FISA itself has no expiration date. Journalist Glenn Greenwald criticized Craig for the "flat-out false" statement. However, in an interview with Greenwald, Craig said that, in explaining to Risen why Obama intended to compromise, he meant to say that certain existing warrants, which had issued under recently expired provisions of FISA, would soon expire themselves unless compromise could be reached on a pending broad amendment of FISA. Said Craig, Obama concluded it was better to compromise.[26]

During the campaign, Craig "seemed on a mission to destroy Hillary's political future." He emerged as "an outspoken critic of Hillary's foreign policy experience and ... a leading contender to be secretary of state after Obama got the nomination."[16]

In late summer and fall 2008, Craig, a skilled trial lawyer, assumed the role of John McCain in Obama's preparations for the presidential debates.[23] The campaign expected "that McCain would condescend to Obama as a wet-behind-the-ears rookie" and Craig played his role as such.[23] Craig-as-McCain "glowered" at Obama in debate prep, saying, "Do not lecture me about the war. Do not tell me how to deploy men in combat. I was flying a jet over Vietnam when you were in grade school."[23] Obama was tutored to remain unflinching and counterattack by listing McCain's past misjudgments.[23] In the 2004 presidential election, Craig played a similar role in preparing John Kerry for the debates; Craig played George W. Bush in practice sessions.[27]

White House Counsel in Obama administration

[edit]

In its November 2008 issue, shortly before the 2008 presidential election, the ABA Journal speculated that Craig might be named Secretary of State in an Obama administration.[28] Craig also reportedly hoped for that position or another foreign policy post in the Obama administration, which did not materialize.[29] Obama ultimately appointed Craig to serve as his first White House Counsel.[29] Craig served in that post from January 2009 to January 2010.[7]

In his first year in the Obama administration, Craig handled "one of the most difficult portfolios in the West Wing."[30] Craig drafted the executive order banning the use of torture and another executive order which ordered the closure within a year of the Guantanamo Bay prison camp (which never materialized).[30] Over the objections of the Central Intelligence Agency, Craig also recommended the release of the "Torture Memos" of the Office of Legal Counsel of the U.S. Department of Justice.[4][30] In an interview in 2011 (after leaving his post as White House counsel), Craig said of the release of the memos: "I think the President made the right decision. It was in the public interest, and it did no damage to national security."[4] Craig added that the memos were the subject of a Freedom of Information Act suit and that he believed that the likelihood of a judge ordering those memos released was high in any case.[4]

Craig also "was at the center of the White House decision to reverse itself and withhold photographs of abuse of detainees."[30]

As White House counsel, Craig also oversaw the successful confirmation of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court of the United States.[29] Craig oversaw the vetting of several prospective nominees and, once Sotomayor was selected, helped prepare her for Senate confirmation hearings.[4][31][32]

Since the summer of 2009, "word had been leaking that Greg Craig's days [as White House Counsel] were numbered and that Obama campaign legal counsel Bob Bauer would be moving in to take Craig's spot."[33] Craig did not know who was responsible for the sustained leaks, although "he suspected they were driven by someone in the White House who was frustrated with the slow progress on shuttering" the Guantanamo Bay prison camp.[33] Nina Totenberg of NPR reported that "There doesn't seem to be much doubt that these leaks came at least indirectly from Rahm Emanuel," the White House chief of staff.[33] Jonathan Alter reported that Craig and Emanuel had a bad relationship, with Emanuel believing that Craig was attempting "to build up his own mini-National Security Council instead of focusing on bread-and-butter legal issues."[34] Alter also reported that Emanuel became enraged when Craig personally traveled with four Chinese Muslim Uighurs released from Guantanamo to Bermuda.[34]

By late October 2009, The New York Times reported that Craig had "for months now ... endured speculation in print and around the White House about whether he is on the way out."[35] Craig stated then that he had no plans to leave and that the president had faith in him, but the Times reported that "colleagues and Democrats close to the White House said they expected him to move on around the end of the year, and they have been talking about possible replacements."[35] By that time, Craig's authority had diminished: Emanuel had assigned Pete Rouse to handle Guantánamo issues, and, once after Craig started the search that led to the nomination of Sonia Sotomayor, assigned Ronald A. Klain and Cynthia Hogan to handle the confirmation.[30][35]

Jonathan Alter reported that Obama "tried to avoid a high-profile ouster" of Craig by offering him an appointment to a federal judgeship, which Craig declined.[34] Craig was subsequently forced out, learning of his impending ouster while reading the morning paper.[34]

On November 13, 2009, the White House announced that Craig would leave his post at the end of the year, and would be replaced by Robert Bauer.[30][36][37]

Craig's ouster following the "whisper campaign" against him angered his friends and supporters inside and outside the White House, who viewed him as a scapegoat.[30][34][35][37] Obama's handling of Craig's resignation was also criticized in the media. Steve Clemons called it "the assassination of Greg Craig" and said that "the White House counsel was done in by a scurrilous leaks campaign."[33] Maureen Dowd wrote that "the way the Craig matter was handled sent a chill through some Obama supporters, reminding them of the icy manner in which the Clintons cut loose Kimba Wood and Lani Guinier."[38] Elizabeth Drew called it "the shabbiest episode of [Obama's] presidency."[38]

Craig's resignation took effect on January 3, 2010.[37] He became the highest-ranking official to leave the Obama administration up until that point.[30]

Private practice after the White House

[edit]Craig stated that he had planned to return to Williams & Connolly from the White House until he got a call from an old friend, Clifford Sloan, and a new friend, Joseph H. Flom, who asked him to join their law firm, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, to establish a crisis-management team and a new practice group focusing on global issues and litigation strategies.[4] On January 27, 2010, Skadden announced that Craig had joined the firm's Washington, D.C. office as a Global Policy and Litigation Strategy Practice Group partner.[39]

In April 2010, it was reported that Craig, as a Skadden partner, was representing the investment banking firm Goldman Sachs; the firm engaged Craig to advise it on litigation strategy in a Securities and Exchange Commission civil suit.[40] When asked about Craig's new role, Deputy White House Press Secretary Bill Burton said that the administration did not have any advance knowledge of Craig's new role and also said, "I assume that people who leave the administration know [the Obama administration's rules barring former White House officials from lobbying for two years after leaving office] and are following those rules."[40] Craig said "I am a lawyer, not a lobbyist. Goldman Sachs has hired me as a lawyer—to provide legal advice and to assist in its legal representation—and that is what I am doing."[40] Legal representation was not covered by the Obama administration's ban.[40]

In 2011, Craig initially represented former Senator John Edwards, a former presidential and vice presidential candidate, in the federal prosecution of Edwards on charges of illegally using campaign funds to cover up his affair with Rielle Hunter.[41][42] Edwards was subsequently acquitted.[42]

In 2012, Craig co-chaired (with former Republican congressman Vin Weber) a bipartisan task force formed by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy which looked into American policy toward Egypt, then led by President Mohamed Morsi.[43] The task force recommended a middle ground on continuing U.S. economic and military aid to Egypt; the group's report, released in November 2012, called for "an approach whereby the United States continues to provide substantial economic and military aid while linking both direct support and backing for international financial support to Egyptian cooperation on key U.S. interests."[43]

Craig led a team of lawyers from Skadden who were commissioned by the government of Ukraine under President Viktor Yanukovich to look into errors in the trial of former Ukrainian prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko on abuse-of-power charges.[44] The report, released in December 2012, found that Tymoshenko was denied legal counsel at "critical stages" of the trial and that her lawyers were wrongly barred from calling witnesses in her defense.[44] The report concluded that Tymoshenko's right to a fair trial "appears to have been compromised to a degree that is troubling under Western standards of due process and the rule of law."[44] However, the report also concluded that Tymoshenko's conviction was supported by the evidence presented at trial and rejected the claim that the prosecution of Tymoshenko was politically motivated by Yanukovich to obstruct the Ukrainian opposition.[44] Tymoshenko's attorneys rejected that finding, saying that the report was not independent because it was commissioned by the Ukrainian government, which paid Skadden an undisclosed sum of money,[44] and human rights organizations regarded the report as a "whitewash."[45]

Craig promoted the report to journalists and members of Congress without much success.[46] Some experts said that Craig should have registered as a foreign agent, as the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) requires those to lobby on behalf of foreign governments to register;[46] however, Craig's attorneys stated that Craig "never disseminated Skadden's report on the Tymoshenko trial to U.S. government officials, and he did not discuss Skadden's findings with officials in the executive branch or the Congress or their staffs," and "was not required to register under FARA."[47] In January 2019, Craig's former law firm, Skadden, paid $4.6 million to the U.S. government in disgorgement as part of a civil settlement.[48][49][50]

Indictment and acquittal

[edit]In April 2018, Craig resigned from Skadden following the indictment of Alex van der Zwaan, a lawyer at the firm's London office. Craig was the lead attorney supervising the firm's work for former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, in which van der Zwaan participated. Van der Zwaan was later charged as a result of the Mueller investigation, and he pleaded guilty to making false statements.[45][51] Following a referral from Mueller's office, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York (USAO-SDNY) in Manhattan investigated Craig and others, including ex-lobbyist Tony Podesta and former Republican U.S. Representative Vin Weber, as part of a broader investigation into the activities of Paul Manafort.[52]

Geoffrey S. Berman, who was U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York from 2018 to 2020, wrote in his 2022 memoirs that, throughout his two and a half years as U.S. attorney, officials in Trump's Justice Department repeatedly attempted to interfere with the office to politically benefit Trump, and that these officials "kept demanding that I use my office to aid them politically."[53] Berman wrote that USAO-SDNY had come under a level of political pressure from Trump officials that was "unprecedented and scary," and that he rebuffed these requests.[53] In June 2020, Trump, angered by USAO-SDNY's investigations into Trump allies Michael Cohen and Rudy Giuliani, fired Berman.[53] Berman said that, following his office's investigation, USAO-SDNY concluded that Craig did not commit a FARA violation and had decided not to pursue charges against him, but that in September 2018, a Trump Justice Department official, Edward O'Callaghan, contacted Berman's office and asked him to charge Craig before the 2018 midterm elections, saying that "It's time for you guys to even things out" after the indictments of Cohen and Chris Collins, a Republican congressman and Trump ally.[53][54][55] O'Callaghan denied making the statements.[55]

The Justice Department ultimately passed the case to federal prosecutors in Washington, D.C.[46] In early April 2019, Craig's lawyers said that they expected him to be indicted by Mueller on charges of concealing and falsifying material facts relating to the investigation's inquiry into possible FARA violations, centering around the work he performed in 2012.[56][57] Craig was indicted on April 11, 2019,[58] on a single count of making false statements.[55] The indictment came after the U.S. Attorney for D.C. rejected Berman's position that an indictment was unwarranted and inappropriate.[53] The indictment alleged that Manafort hired Craig and others at Skadden to write a report which would show favor towards Yanukovich, who was known for his close ties to the Russian government, and that Manafort paid them "millions of dollars".[59][60][61]

The indictment was criticized as weak and politicized.[54] Craig pleaded not guilty,[62] and testified in his own defense.[63] Prosecutors did not call Manafort as a witness.[63] The jury was informed by the judge not to consider possible offenses committed before October 2013 because the statute of limitations for those actions had run out.[63] On September 4, 2019, the jury acquitted Craig after less than five hours of deliberation.[63] Berman, the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, wrote in his 2022 memoirs that the acquittal "was vindication, but the case should never have been brought. .... The case was too weak to be brought. It was inappropriate to be brought. And that's what the trial showed."[53] In 2022, following the publication of Berman's book, the Senate Judiciary Committee opened an investigation into allegations that the Trump administration sought to use the U.S. Attorney's office in SDNY for partisan reasons.[55]

Personal life

[edit]Craig is married to Derry Noyes.[2][9] The two were married on July 27, 1974, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Derry is the daughter of Eliot Noyes, the noted industrial designer known for his work on the IBM Selectric typewriter.[64] Derry Craig is a graphic designer.[9] The couple have five children.

Craig lives in the Cleveland Park neighborhood of Washington, in a home purchased for $2 million in 1990.[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lucas, Ryan (September 4, 2019). "Jury Finds Ex-White House Counsel Craig Not Guilty Of Lying To Government". NPR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lewis, Neil A. (November 8, 2008). "The New Team: Gregory B. Craig". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bayot, Jennifer (March 11, 2005). "William Craig, 90, Leader of Colleges in 2 States, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kashino, Marisa M. (May 23, 2011). "Obama White House Counsel Gregory Craig: What I've Learned". Washingtonian.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eisler, Kim (July 1, 2000). "Greg Craig's A-List". Washingtonian.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lin, Kevin (February 11, 2009). "Gregory B. Craig '67". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gregory B. Craig, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (accessed July 22, 2015).

- ^ "Group photo of 1966 Harvard Krokodiloes from group's website". kroks.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grove, Lloyd; Harris, John F. "Crisis Quarterback: Gregory Craig Is Calling the Plays On Clinton's Team". The Washington Postdate=November 19, 1998.

- ^ a b Jones, Ashby (January 27, 2010). "Why Greg Craig Chose Skadden Over Williams & Connolly". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (September 11, 1979). "Jury Picked In Antonelli, Yeldell Trial". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Palazzolo, Joe (July 17, 2009). "A Long Career Near the Spotlight But Rarely in It". Main Justice.

- ^ Brown, Emma (July 23, 2010). "D.C. real estate, parking-lot magnate Dominic F. 'Nick' Antonelli Jr. dies at 88". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e Seccombe, Mike (August 4, 2008). "Defender of President Clinton, Greg Craig Stumps for Obama". Vineyard Gazette.

- ^ a b c d Myers, Steven Lee (November 1, 1997). "The Jiang Visit: In Washington, After Jiang Moves On, Albright Appoints New Coordinator to Focus on Tibet". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Eisler, p. 275.

- ^ a b c "Interview: Georgory Craig". PBS Frontline. July 2000. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Spivak, Russell (June 5, 2017). "A Premature Primer: How Do Impeachment Proceedings Actually Work?". Lawfare.

- ^ a b McKinnon, John D.; Farnum, T.W. (April 4, 2009). "Hedge Fund Paid Summers $5.2 Million in Past Year". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Greg Craig Discusses the Elian Gonzalez Custody Battle Archived 2008-09-16 at the Wayback Machine (transcript of April 22, 2000 CNN interview).

- ^ a b Hsu, Spencer S.; Helderman, Rosalind S. (September 4, 2019). "Gregory Craig found not guilty of lying to investigators probing work to aid Ukraine president". The Washington Post.

- ^ Eisler, Masters of the Game, p. 273.

- ^ a b c d e "Ch. 6: Battling it Out in the Great Debates". Newsweek. November 6, 2008.

- ^ Packer, George (January 28, 2008). "The Choice: The Clinton-Obama battle reveals two very different ideas of the Presidency". The New Yorker.

- ^ a b c Risen, James (July 2, 2008). "Obama Voters Protest His Switch on Telecom Immunity". The New York Times.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (July 2, 2008). "Obama advisor Greg Craig: Adding insult to injury". Salon.

- ^ VandeHei, Jim (September 13, 2004). "Debate Team Helps Kerry Prepare for Face-Off With Bush". The Washington Post.

- ^ Carter, Terry; Ward, Stephanie Francis (November 2008). "The Lawyers Who May Run America". ABA Journal. Chicago, Illinois: American Bar Association.

- ^ a b c Kornblut, Anne E.; Nakashima, Ellen (November 13, 2009). "White House counsel poised to give up post". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zeleny, Jeff (November 13, 2009). "Craig Steps Down as White House Lawyer". The New York Times.

- ^ A Conversation With Former White House Counsel Gregory B. Craig Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (March 31, 2010).

- ^ Miller, Erin (March 5, 2010). "Lecture by Gregory Craig: Picking Supreme Court Justices". SCOTUSBlog.

- ^ a b c d Clemons, Steve (November 16, 2009). "The Assassination of Greg Craig". The Daily Beast.

- ^ a b c d e Hohmann, James (May 18, 2010). "Book: White House offered Greg Craig judgeship". Politico.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Peter (October 21, 2009). "Fate of White House Counsel Is in Doubt". The New York Times.

- ^ The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Statement from President Obama on Greg Craig and Bob Bauer (November 13, 2009).

- ^ a b c Henry, Ed (November 13, 2009). "Officials: Top White House lawyer to be pushed out". CNN.

- ^ a b Dowd, Maureen (November 25, 2009). "Thanks For the Memories". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ Former Obama White House Counsel Gregory B. Craig Joins Skadden Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (press release), Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (January 27, 2010).

- ^ a b c d Baker, Peter (April 21, 2010). "Ex-Adviser to Obama Now Lawyer for Goldman". The New York Times.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (June 3, 2011). "Edwards Indicted in Campaign Fund Case". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Gerstein, Josh (June 1, 2012). "John Edwards: How the prosecution stumbled". Politico.

- ^ a b Baker, Peter (November 28, 2012). "Bipartisan Group Recommends Middle Ground on Aid to Egypt". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Herszenhorn, David M.; Sanger, David E. (December 12, 2012). "Failings Found in Trial of Ukrainian Ex-Premier". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Dilanian, Ken (April 24, 2018). "Former Obama lawyer Greg Craig leaves firm after brush with Mueller probe". NBC News.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, Matthew; Vogel, Kenneth P.; Benner, Katie (August 1, 2018). "Mueller Passes 3 Cases Focused on Illicit Foreign Lobbying to Prosecutors in New York". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Christine Simmons, Experts See Few Parallels as Skadden's Ukraine Work Comes Under Fire, New York Law Journal (September 18, 2018).

- ^ Overby, Peter (April 12, 2019). "Lobbyists See the Indictment Of Powerful Lawyer Gregory Craig As A Warning". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "Prominent Global Law Firm Agrees to Register as an Agent of a Foreign Principal". U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. January 17, 2019.

- ^ Matthew T. Sanderson (February 15, 2019). "Recent FARA Development: Skadden Pays $4.6 Million in Settlement". FARA.us.

- ^ Cassens Weiss, Debra (April 24, 2018). "Greg Craig, former White House counsel and lead lawyer on Ukraine report, leaves Skadden". ABA Journal. Chicago, Illinois: American Bar Association. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Wang, Christine (July 31, 2018). "Federal prosecutors said to be investigating lobbyist Tony Podesta after special counsel referral". CNBC. Retrieved 2018-08-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryan Chatelain, Ex-U.S. attorney in book: Trump DOJ repeatedly interfered with office for political reasons, Spectrum News NY1 (September 12, 2022).

- ^ a b Andrew Prokopandrew, A new book claims Trump's efforts to politicize the Justice Department were worse than we knew: Fired US Attorney Geoffrey Berman has some stories to tell., Vox (September 8, 2022).

- ^ a b c d Benjamin Weiser, Senate to Investigate Charge That Trump Meddled in Prosecutor's Office, New York Times (September 12, 2022).

- ^ Darrah, Nicole (10 April 2019). "Lawyers for Greg Craig, ex-Obama White House counsel, say they expect him to be charged with foreign lobbying violations". Fox News. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

FARA violations were only rarely prosecuted until Mueller took aim at Paul Manafort

- ^ Wilkie, Christina; Breuninger, Kevin (11 April 2019). "Obama White House counsel Gregory Craig charged by federal prosecutors over alleged Ukraine lies". CNBC. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

The charges reportedly stem from the federal investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential election led by special counsel Robert Mueller

- ^ Vogel, Kenneth P.; Benner, Katie (April 11, 2019). "Gregory Craig, Ex-Obama Aide, Is Indicted on Charges of Lying to Justice Dept". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ Farrell, Greg; Harris, Andrew M. (April 16, 2019). "In Craig Indictment, a Top Law Firm Tries to Hide Lobbying". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ Maddow, Rachel (April 12, 2019). "Former Democratic W.H. counsel indicted in Manafort case fallout". MSNBC. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ Helderman, Rosalind S.; Hamburger, Tom (April 10, 2019). "Gregory Craig, ex-Obama White House counsel, expects to be charged in relation to Ukrainian work with Manafort, his lawyers say". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ Montague, Zach (April 12, 2019). "Gregory Craig Pleads Not Guilty to Lying to Justice Dept". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d LaFraniere, Sharon (September 4, 2019). "Gregory Craig Acquitted on Charge of Lying to Justice Department". The New York Times.

- ^ Eisler, Kim (2010). Masters of the Game: Inside the World's Most Powerful Law Firm. London, England: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 70. ISBN 9781429921190.

- ^ "Welcome to Obamaland". Washingtonian. August 1, 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kim Eisler, Masters of the Game: Inside the World's Most Powerful Law Firm (Thomas Dunne Books, 2010).

External links

[edit]- Official biography from Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Gregory B. Craig collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- 1945 births

- Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge

- American lawyers

- American political consultants

- Clinton administration personnel

- Directors of Policy Planning

- Harvard University alumni

- Lawyers from Washington, D.C.

- Living people

- Obama administration personnel

- People acquitted of crimes

- People from Cleveland Park

- People from Middlebury, Vermont

- Phillips Exeter Academy alumni

- Politicians from Norfolk, Virginia

- Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom people

- Washington, D.C., Democrats

- White House Counsels

- Williams & Connolly people

- Yale Law School alumni

- Public defenders

- Members of the defense counsel for the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton