The Grand Budapest Hotel

| The Grand Budapest Hotel | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

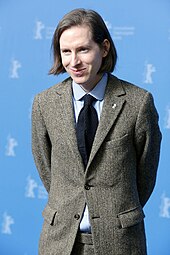

| Directed by | Wes Anderson |

| Screenplay by | Wes Anderson |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Yeoman |

| Edited by | Barney Pilling |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Fox Searchlight Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[2] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[3] |

| Box office | $174.6 million[3] |

The Grand Budapest Hotel is a 2014 comedy-drama film written, directed, and co-produced by Wes Anderson. Ralph Fiennes leads a 17-actor ensemble cast as Monsieur Gustave H., famed concierge of a 20th-century mountainside resort in the fictional Eastern European country of Zubrowka. When Gustave is framed for the murder of a wealthy dowager (Tilda Swinton), he and his recently befriended protégé Zero (Tony Revolori) embark on a quest for fortune and a priceless Renaissance painting amidst the backdrop of an encroaching fascist regime. Anderson's American Empirical Pictures produced the film in association with Studio Babelsberg, Fox Searchlight Pictures, and Indian Paintbrush's Scott Rudin and Steven Rales. Fox Searchlight supervised the commercial distribution, and The Grand Budapest Hotel's funding was sourced through Indian Paintbrush and German government-funded tax rebates.

Anderson and longtime collaborator Hugo Guinness conceived The Grand Budapest Hotel as a fragmented tale following a character inspired by a common friend. They initially struggled in brainstorming, but the experience touring Europe and researching the literature of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig shaped their vision for the film. The Grand Budapest Hotel draws visually from Europe-set mid-century Hollywood films and the United States Library of Congress's photochrom print collection of alpine resorts. Filming took place in eastern Germany from January to March 2013. French composer Alexandre Desplat composed the symphonic, Russian folk-inspired score, which expanded on his early work with Anderson. The film explores themes of fascism, nostalgia, friendship, and loyalty, and further studies analyze the function of color as an important storytelling device.

The Grand Budapest Hotel premiered in competition at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival on February 6, 2014. The French theatrical release on February 26 preceded the film's global rollout, followed by releases in Germany, North America, and the United Kingdom on March 6–7. The Grand Budapest Hotel is now considered as Anderson's magnum opus and has been assessed as one of the greatest films of the 21st century,[4][5][6][7] with particularly praise for its craftsmanship and acting as well as occasional criticism centered on the film's approach to subject matter, fragmented storytelling, and characterization. It earned $174 million in box office revenue worldwide, making Anderson's highest-grossing feature to date. The film was nominated for nine awards at the 87th Academy Awards including Best Picture, winning four, and received numerous other accolades.

Plot

[edit]In a cemetery in the former nation of Zubrowka,[a] a woman visits the shrine of a renowned writer, known simply as "Author", reading his most-cherished book: The Grand Budapest Hotel. The book, written in 1985, recounts the 1968 vacation of the young writer at the once-grand, then-drab hotel. There, he meets its owner, Zero Moustafa, who tells his rags to riches story at dinner.

In 1932, Zero is an illegal refugee escaping a war waged by a fascist regime, which killed his entire family. He is hired as a lobby boy supervised by Monsieur Gustave H., the hotel's concierge. Gustave strikes up affairs with old, wealthy clients, including dowager Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe-und-Taxis (known as Madame D.), with whom he's had a nearly two-decade affair. She mysteriously dies a month after her last hotel visit so Gustave and Zero visit her estate, where relatives come for the reading of her will. There, her attorney, Deputy Vilmos Kovacs, announces a recent codicil which bequeaths the famous Renaissance painting Boy with Apple to Gustave. Madame D.'s son and an agent of the regime, Dmitri, refuses to let it happen. Gustave and Zero abscond with the painting, hiding it in a safe in the Grand Budapest.

After a testimony by Madame D.'s butler Serge X, Gustave is arrested by Inspector Alfred J. Henckels for Madame D.'s murder; Serge then goes into hiding. Gustave befriends a gang during his imprisonment and provides them with pastries from Mendl's, a well-known bakery. After extensive research of the prison, one of Gustave's cellmates, Ludwig, tells the gang that they can escape via a storm-drain sewage system. Convinced to join the prison break, Gustave has Zero place hammers, chisels, and sawblades inside pastries made by Agatha, an apprentice of Herr Mendl and Zero's fiancée. The guard responsible for checking contraband cannot bring himself to break open the pastries since Mendl's pastries are works of art. During the prison break, the group of convicts runs into guards who secretly gamble at night, and convict Gunther is forced to sacrifice himself to dispatch the guards. The rest of the group manages to escape and disperse. Meanwhile, Dmitri sends his hitman, J. G. Jopling, to kill Kovacs after questioning his loyalty, as well as Serge's sister for hiding his whereabouts.

When Zero and Gustave are reunited, they set out to prove Gustave's innocence with the assistance of a fraternity of concierges known as the Society of the Crossed Keys, which locates Serge and facilitates a meeting between him, Gustave and Zero. Serge reveals that he was pressured to implicate Gustave by the real killer, Dmitri, and that Madame D. had a missing second will, which would only take effect should she be murdered. Jopling arrives and kills Serge, leaving Gustave and Zero without a witness, then tries to flee. After a chase through the snow, Gustave is left dangling off a cliff at the mercy of Jopling. Before it is too late, Zero rescues Gustave by pushing Jopling off the cliff, and the two men continue their escape from swarming Zubrowkan troops led by Henckels.

Gustave, Zero, and Agatha return to the Grand Budapest to find it converted into a fascist headquarters by Dmitri. Agatha sneaks in to retrieve the painting but is spotted by Dmitri. Gustave and Zero rush in to save Agatha, but Dmitri shoots at them and initiates a melee with Zubrowkan troops, which Henckels stops. On the back of the painting, the group finds Madame D.'s second will, which reveals her as the Grand Budapest's owner and bequeaths it to Gustave. He is exonerated in court, while Dmitri becomes the main suspect and flees the country. Over time, Gustave becomes one of the wealthiest Zubrowkans, and Zero and Agatha are wed. However, while the three are later traveling by train, soldiers come by and destroy Zero's refugee documents; Gustave tries to fend them off but is killed. His own will bequeaths the hotel and his fortune to Zero. He maintains the Grand Budapest up to its eventual decline in memory of Agatha who, like their infant son, died from Prussian Grippe.[10]

Cast

[edit]- Ralph Fiennes as Monsieur Gustave H., the Grand Budapest Hotel's renowned concierge

- Tony Revolori as Zero Moustafa, the newly hired bellhop mentored by Gustave

- F. Murray Abraham as the elderly Zero

- Adrien Brody as Dmitri Desgoffe-und-Taxis, Madame D.'s son

- Willem Dafoe as J. G. Jopling, a ruthless hitman working for Dmitri

- Saoirse Ronan as Agatha, an apprentice baker and Zero's love interest

- Tilda Swinton as Dowager Countess Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe-und-Taxis, known as Madame D., a wealthy dowager countess and the secret owner of the hotel

- Edward Norton as Albert Henckels, the police investigator of Madame's murder

- Mathieu Amalric as Serge X, a shifty butler who works for Madame D

- Jeff Goldblum as Deputy Vilmos Kovacs, the lawyer representing Grand Budapest interests

- Harvey Keitel as Ludwig, leader of a prison gang at Checkpoint Nineteen

- Tom Wilkinson as Author, writer of The Grand Budapest Hotel

- Jude Law as the young Author in 1968

- Bill Murray as M. Ivan, Gustave's friend and one of several concierges affiliated with the Society of the Crossed Keys

- Jason Schwartzman as M. Jean, the Grand Budapest's concierge in 1968

- Owen Wilson as M. Chuck, a Society of the Crossed Keys concierge

- Léa Seydoux as Clotilde, maid at Schloss Lutz

Other cast members included Larry Pine as Mr. Mosher, Milton Welsh as Franz Müller, Giselda Volodi as Serge's sister, Wolfram Nielacny as Herr Becker, Florian Lukas as Pinky, Karl Markovics as Wolf, Volker Michalowski as Günther, Neal Huff as Lieutenant, Bob Balaban as M. Martin, Fisher Stevens as M. Robin, Wallace Wolodarsky as M. Georges, Waris Ahluwalia as M. Dino, Jella Niemann as the young woman, and Lucas Hedges as a pump attendant.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Drafting of The Grand Budapest Hotel story began in 2006, when Wes Anderson produced an 18-page script with longtime collaborator Hugo Guinness.[11] They imagined a fragmented tale of a character inspired by a mutual friend, based in modern France and the United Kingdom.[12][13] Though their work yielded a 12-minute-long cut,[14] collaboration stalled when the two men were unable to coalesce a uniform sequence of events to advance their story.[13] By this time, Anderson had begun researching the work of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, with whom he was vaguely familiar. He became fascinated with Zweig, gravitating to Beware of Pity (1939), The World of Yesterday (1942), and The Post Office Girl (1982) for their fatalist mythos and Zweig's portrait of early twentieth-century Vienna.[15][16] Anderson also used period images and urbane Europe-set mid-century Hollywood comedies as references.[17][18] He ultimately pursued a historical pastiche with an alternate timeline, disillusioned with popular media's romanticism of pre-World War II European history.[19] Once The Grand Budapest Hotel took definite form, Anderson resumed the scriptwriting, finishing the screenplay in six weeks.[14] The producers tapped Jay Clarke to supervise production of the film's animatics, with voiceovers by Anderson.[20][14]

Anderson's sightseeing in Europe was another source of inspiration for The Grand Budapest Hotel's visual motifs.[21] The writer-director visited Vienna, Munich, and other major cities before the project's conception, but most location scouting began after the Cannes premiere of his coming-of-age drama Moonrise Kingdom (2012). He and the producers toured Budapest, small Italian spa towns, and the Czech resort Karlovy Vary before a final stop in Germany,[21] consulting hotel staff to develop an accurate idea of a real-life concierge's work.[14]

Casting

[edit]A seventeen-actor ensemble received star billing in The Grand Budapest Hotel.[22] Anderson customarily employs a troupe of longtime collaborators—Bill Murray, Adrien Brody, Edward Norton, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Harvey Keitel, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, and Jason Schwartzman have worked on one or more of his projects.[23] Norton and Murray immediately signed when sent the script.[24][25] The Grand Budapest Hotel ensemble comprised mostly bit cameos.[26] Because of the limitations of such roles, Brody said that the most significant challenge was balancing the film's comedy with the otherwise solemn subject matter.[27] All were the filmmakers' first casting choices save for Swinton, whom they pursued for Madame D. when Angela Lansbury dropped out as a result of a prior commitment to a Driving Miss Daisy theater production.[28][29] Once hired, actors were encouraged to study the source material to prepare.[30] Dafoe and Fiennes in particular found the animatics helpful in conceptualizing The Grand Budapest Hotel from Anderson's perspective,[30][31] though Fiennes did not refer to them too often as he wanted his acting to be spontaneous.[30]

Anderson desired an English actor to play Gustave, and Fiennes was an actor he sought to work with for several years.[14] Fiennes, surprised by the offer, was eager to depart from his famously villainous roles and found Gustave's panache compelling.[30] Fiennes said he was initially unsure how to approach his character because the extent of Anderson's oversight meant actors could not improvise on set, inhibiting his usually spontaneous performing style.[31] The direction of Gustave's persona then became another question of tone, whether the portrayal be hyper-camp or understated.[30][32] Fiennes drew on several sources to shape his character's persona,[33] among them his triple role as Hungarian-Jewish men escaping fascist persecution in the István Szabó-directed drama Sunshine (1999), his brief stint as a young porter at Brown's Hotel in London,[34] and the experience reading The World of Yesterday.[34] Johnny Depp was reported as an early candidate in the press, claims which Anderson denied,[35] despite later reports that scheduling conflicts had halted negotiations.[29]

Casting director Douglas Aibel was responsible for hiring a suitable actor to play young Zero. Aibel's months-long search for prospective actors proved troublesome as he was unable to fulfill the specifications for an unknown teenage actor of Arabic descent.[14] "We were just trying to leave no stone unturned in the process."[36] Filmmakers held auditions in Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, France, England, and the United States before revising the role's ethnic criterion.[37][36] Eventually the filmmakers narrowed their search to Tony Revolori and his older brother Mario, novices of Guatemalan descent, and Tony landed the part after one taped audition.[36] He and Anderson rehearsed together for over four months before the start of filming to build a rapport.[38] Abraham spent about a week on set filming his scenes as the elderly Zero.[39]

Saoirse Ronan joined The Grand Budapest Hotel in November 2012.[40] Though a longtime Anderson fan, Ronan feared the deadpan, theatrical acting style characteristic of Anderson's films would be too difficult to master.[41] She was reassured by the director's conviction, "He guides everyone extremely well. He is very secure in his vision and he is very comfortable with everything he does. He knows it is going to work."[41] The decision to have Ronan play Agatha in her native Irish accent was Anderson's idea, after experimenting with German, English, and American accents; they felt an Irish accent projected a warm, feisty spirit into Agatha.[42]

Filming

[edit]

The project was director of photography Robert Yeoman's eighth film with Anderson. Yeoman participated in an early scouting session with Anderson, recording footage with stand-in film crew to assess how certain scenes would unfold.[43] Yeoman drew on Vittorio Storaro's dramatic lighting techniques in the romantic musical One From the Heart (1982).[17][44] Filmmakers shot The Grand Budapest Hotel in ten weeks,[14] from January to March 2013 in eastern Germany,[45][46] where it qualified for a tax rebate financed by the German government's Federal Film Fund and Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg.[45][47][48] They also found Germany attractive because the production base was geographically confined, facilitating efficient logistics,[49] but the frigid weather and reduced daylight of early winter disrupted the shooting schedule, compounded by the slow film stock used for the camerawork. To rectify the issue, the producers used artificial lighting, expedited the daytime work schedule, and filmed night scenes at dusk.[17]

Principal photography took place at the Babelsberg Studio in suburban Berlin and in Görlitz, a mid-sized border town on the Lusatian Neisse on Germany's eastern frontier.[50] The filmmakers staged their largest interior sets at the vacant twentieth-century Görlitzer Warenhaus, whose atrium doubled for the Grand Budapest Hotel lobby. The top two floors housed production offices and storage space for cameras and wardrobe.[50][51] Anderson at one point considered buying the Warenhaus to save it from demolition.[52] He and the producers eyed vacant buildings because they could exercise full artistic control, and scouting active hotels that often enforce heavy shooting restrictions would call into question The Grand Budapest Hotel's integrity.[17] Exterior shots of the eighteenth-century estate Hainewalde Manor and interior shots of Schloss Waldenburg stood in for the Schloss Lutz estate.[53] Elsewhere in Saxony, production moved to Zwickau—shooting at the Osterstein Castle—and the state capital Dresden, where scenes were filmed at the Zwinger and the Pfunds Molkerei creamery.[50]

Cinematography

[edit]Yeoman shot The Grand Budapest Hotel on 35 mm film using Kodak Vision3 200T 5213 film stock from a single Arricam Studio camera provided by Arri's Berlin office.[43] His approach entailed the use of a Chapman-Leonard Hybrid III camera dolly for tracking shots and a geared head to achieve most of the film's rapid whip pans. For whip pans greater than 90 degrees, the filmmakers installed a fluid head from Mitchell Camera Corporation's OConnor Ultimate product line for greater fidelity.[43] Anderson requested Yeoman and project key grip Sanjay Sami focus on new methods for shooting the scenes.[43] Thus they used the Mad About Technology Towercam Twin Peek,[54] a telescoping camera platform, to traverse between floors, sometimes in lieu of a camera crane. For example, when a lantern drops to the basement from a hole in the cell floor in the Checkpoint Nineteen jailbreak scene, the filmmakers suspended the towercam upside-down, a setup which allowed the camera to descend to the ground.[43]

The Grand Budapest Hotel uses three aspect ratios as framing devices which streamline the film's story, evoking the aesthetic of the corresponding periods.[55][56] The multifarious structure of The Grand Budapest Hotel emerged from Anderson's desire to shoot in 1.37:1 format, also known as Academy ratio.[57] Production used Academy ratio for scenes set in 1932, which, according to Yeoman, provided the filmmakers with greater-than-routine headroom. He and the producers referred to the work of Ernst Lubitsch and other directors of the period to acclimate to the compositions produced from said format.[43] Filmmakers formatted modern scenes in standard 1.85:1 ratio, and the 1968 scenes were captured in widescreen 2.40:1 ratio with Technovision Cooke anamorphic lenses. These lenses produced a certain texture, one that lacked the sharpness of Panavision's Primo anamorphic lenses.[43]

Yeoman lit interior shots with tungsten incandescent fixtures and DMX-dimmer-controlled lighting. The crew made the Warenhaus ceiling from stretched muslin rigged with twenty 4K HMI lamps, an arrangement wherein the reflected light penetrated the skylight, accentuating the set's daylighting. Yeoman preferred the lighting choice because the warm tungsten fixtures contrasted with the coolish daylight.[43] When shooting deliberately less inviting hotel sets, such as Zero and Gustave's small bedrooms and the Grand Budapest's servants' quarters, the filmmakers combined fluorescent lighting, paper lanterns, and bare incandescent lights for historical accuracy.[43]

The Stuttgart-based LUXX Studios and Look Effects' German branch (also in Stuttgart) managed most of The Grand Budapest Hotel's visual effects, under the supervision of Gabriel Sanchez.[43][58] Their work for the film comprised 300 shots, created by a small cadre of specialized artists.[58] The development of the film's effects was swift, but at times difficult. Sanchez did not work on set with Anderson as Look Effects opened their Stuttgart headquarters after The Grand Budapest Hotel filming wrapped, and therefore was only able to reference his prior experience with the director. The California-based artist also became homesick working his first international assignment.[58] Only four artists from the newly assembled team had experience working on a multi-million dollar studio set.[58] Hollywood based Modern Videofilm used DaVinci Resolve to give the movie its final colors.[59]

Creation of the effects was daunting because of their technical demands. The filmmakers camouflaged some of the stop-motion and matte effects in the forest-set chase scene to convey the desired intensity, and enhancing the snowscape with particle effects posed another challenge.[58] Sanchez cites the observatory and hotel shots as work that best demonstrate his special effects team's ingenuity. To achieve the aging brutalist design of the 1968 Grand Budapest, they generated computer models supplemented with detailed lighting, matte effects and shadowy expanses.[58] The crew used a similar technique in developing digital shots of the observatory; unlike the hotel, the observatory's base miniature was presented in pieces. They rendered the observatory with 20 different elements, data furthermore enhanced at Anderson's request. It took about one hour per shot to complete the final digital rendering.[58]

Set design

[edit]Adam Stockhausen—another Anderson associate—was responsible for The Grand Budapest Hotel's production design. He and Anderson collaborated previously on The Darjeeling Limited (2007) and Moonrise Kingdom.[60] Stockhausen researched the United States Library of Congress's photochrom print collection of alpine resorts to source ideas for the film's visual palette. These images showcased little of recognizable Europe, instead cataloging obscure historical landmarks unknown to the general public.[61][62] The resulting stylistic choice is a warm, bright visual palette pronounced by soft pastel tonalities. Some of The Grand Budapest Hotel interior sets contrast this look in interior shots, primarily Schloss Lutz and the Checkpoint Nineteen prison: the imposing hardwoods, intense greens and golds of the Schloss Lutz evoke oppressive wealth, and the derelict Checkpoint Nineteen decays in a cool bluish-gray tint.[53]

The filmmakers relied on matte paintings and miniature effect techniques to play on perspective for elaborate scenes, creating the illusion of size and grandeur. Under the leadership of Simon Weisse, scale models of structures were constructed by a Berlin-based propmaking team at Studio Babelsberg in tandem with the Görlitz shoot.[63][64] Weisse joined The Grand Budapest Hotel's design staff after coming to the attention of production manager Miki Emmrich, with whom he worked on Cloud Atlas (2012).[63] Anderson liked the novelty of miniatures, having used them in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) and more extensively in Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009).[64]

Weisse and his propmakers built three major miniature models: the 1⁄8-scale forest set, the 1⁄12-scale observatory, and the 1⁄18-scale Grand Budapest Hotel set, based on art director Carl Sprague's conceptual renderings. The Grand Budapest Hotel set comprised the hotel building atop a wooded ledge with a funicular, bound by a Friedrichian landscape painting superimposed with green-screen technology.[64] Designers sculpted the 3-meter-high (9.8 ft) hotel with silicone resin molds and etched brass embellishment. Photos of the Warenhaus set were then glued in boxes installed to each window to convey the illusion of light.[63] The funicular's 35-degree slope required a separate, lateral model.[63][65][66] Timber, soldered brass, fine powdered sugar, and styrofoam were used to construct the observatory set, and polyester fiberfill was the forest model's snow.[63]

The creation of Boy with Apple was a four-month-long process by English painter Michael Taylor, who was inspired by Renaissance portraiture, among them Gabrielle d'Estrées et une de ses sœurs (1594).[67][68][69] Taylor had been approached by one of the producers before receiving the script and source material, and the film's artistic direction piqued his interest. The painter originally worked alone before deferring to Anderson for input when certain aspects of the painting did not match the writer-director's vision.[67] Taylor found the initial process difficult, struggling to be true to Boy with Apple's eclectic sources.[68] He said that while he had been unfamiliar with Anderson's work, that unfamiliarity enabled him to imbue the painting with a unique identity.[67] The producers' casting choice for Boy with Apple's subject was contingent on the character description of a blond-haired boy with the slender, athletic frame of a ballet dancer. They signed Ed Munro, an actor with a theater background, the day after his audition.[67] The filmmakers staged the painting sessions at a Jacobean boarding school, then empty for summer holiday, near Taylor's home in Dorset. Filmmakers dressed Munro in about 50 ornate costumes with velvet cloaks, codpieces and furs, photographed each one, and submitted them to Anderson for approval. Munro, who maintained the same posture and facial expression for several hours, found the costuming uncomfortable.[67] Two Lesbians Masturbating, created by Rich Pellegrino, draws from the work of Expressionist artist Egon Schiele.[70][71]

Ann Atkins was The Grand Budapest Hotel's lead graphic designer.[72] She devised Zubrowkan objects—newspapers, banknotes, police reports and passports—from reference material gathered from the location scouting. Atkins was a novice in film but had valuable expertise in advertising design to reference, producing 20 sketches of a single artifact per day when the on-set shooting peaked.[73] She used an antique typewriter for the mock documents with a dip pen for the embellished handwriting.[72] Among her early tasks was the creation of weathered, worn props for fidelity to the film's timeline. To achieve the appearance of prolonged exposure to air, Atkins blow dried paper dipped in tea.[73] She said, "The beautiful thing about period filmmaking is that you're creating graphic design for a time before graphic designers existed, per se. It was really the craftsmen who were the designers: the blacksmith designed the lettering in the cast iron gates; the glazier sculpted the lettering in the stained glass; the sign-painter drew the lettering for the shopfronts; the printer chose the type blocks for the stationery."[72]

Pastries are an important motif in The Grand Budapest Hotel story.[74] The signature courtesan au chocolat from Mendl's mirrors the French dessert religieuse, a choux-based pastry with a mocha (or chocolate) glaze and vanilla custard filling.[74] A Görlitz pastry chef crafted the courtesan before working with Anderson on the final design.[75]

Costumes

[edit]

Veteran costume designer Milena Canonero endeavored to capture the essence of the film's characters.[76] Canonero researched 1930s uniform design and period artwork by photographers George Hurrell and Man Ray and painters Kees van Dongen, Gustav Klimt, George Grosz and Tamara de Lempicka.[77] Canonero was also influenced by non-period literature and art.[76] Specialized artists then realized her designs in Photoshop, allowing them to work closely to the actors' likenesses.[77] The filmmakers assembled most of the basic costumes in their Görlitz workshop, others from the Berlin-based Theaterkunst, and the uniforms came from a Polish workshop. They rented vintagewear for extras in crowd shots.[77] Canonero used dense mauve and deep-purple AW Hainsworth facecloth for the Grand Budapest uniforms instead of the more subdued colors typical of hospitality uniforms.[77] She researched diverse ideas for the gray-and-black military uniforms, in accordance with script specifications that they not be green or too historically identifiable.[78] Anderson did most of the insignia, occasionally approving designs from Canonero's workshop in Rome.[78]

The filmmakers gave the characters distinct looks. They distinguished men with facial hair to augment their dapper style.[77] Gustave's wardrobe was intended to evoke "a sense of perfection and control" even in his collapsing livelihood.[79] Anderson and Canonero visualized Agatha with a Mexico-shaped facial birthmark and a wheat blade in her hair, costumed to reflect her working-class stature and the brightness of her pastries.[78] Madame was dressed in a silk velvet coat-and-gown-ensemble with Klimtesque handprint patterns and mink trim by Fendi, from a previous professional relationship with Anderson and Canonero. Fendi developed the gray astrakhan fur overcoat for Norton's Albert, and loaned other furs to assist the needs of the shoot.[78][79] To age Swinton, makeup artist Mark Coulier applied soft silicone rubber prosthetics encapsulated in dissolvable plastic molding on her face.[80] Dafoe's Jopling wore a Prada leather coat inspired by outerwear for military dispatch riders, adorned with custom silver knuckle pieces from jeweler Waris Ahluwalia (a close friend of Anderson's).[79] Canonero modified the coat with fine red-wool stitching and a weapons compartment inside the front lapel.[79]

Music

[edit]Anderson recruited Alexandre Desplat to compose the film's Russian folk-influenced score encompassing symphonic compositions and background drones;[81] the balalaika formed the score's musical core.[82] The instrument gave Anderson and music supervisor Randall Poster a chance to immerse themselves in an unfamiliar genre, and they spent about six months consulting experts to hone their vision.[83] Its score's classical roots make The Grand Budapest Hotel unique among Anderson-directed projects, forgoing the writer-director's usual practice of employing a selection of contemporary pop music.[83] Desplat felt his exposure to Anderson's idiosyncratic filmmaking style was integral to articulating an Eastern European musical approach for the film's score.[84] His direction expanded on some of the sounds and instrumentation of Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom. As well, the scope of Desplat's responsibilities entailed differentiating The Grand Budapest Hotel's sprawling cast of characters with distinctive melodic themes and motifs.[85] ABKCO Records released the 32-track score digitally on March 4, 2014.[86] It featured sampled recordings[87] and contributions from orchestras such as the Osipov State Russian Folk Orchestra and a 50-person ensemble of French and Russian balalaika players.[83][88]

Themes and style

[edit]The reticent Anderson did not discuss themes in interviews conducted during the press junkets, lending several interpretations of The Grand Budapest Hotel.[89] Studies cite intertwining messages of tragedy, war, fascism, and nostalgia as the film's thematic center.[90][91][92]

Nostalgia and fascism

[edit]Nostalgia is a major theme in Anderson's repertoire.[93] The Grand Budapest Hotel universe is envisioned with nostalgic yearning, where characters perpetuate the "illusion of a time where they don't belong",[90] the consequence of not so much the recapture of a vanished era than a romanticizing of the past.[94][95][96] One theory among critics suggests "profound" subtext of the science of human memory within the film's nonlinear narrative structure,[97] whereas others saw The Grand Budapest Hotel as an introspection of Anderson's sensibilities both as a writer and as a director.[98] According to the academic Donna Kornhaber, The Grand Budapest Hotel reinforces the increasingly dark subtext of collectivism defining late period Anderson films.[99]

The Grand Budapest Hotel does not directly refer to historical events, rather oblique references contextualize the real time history.[100] The most deliberate of these references allude specifically to Nazism. In perhaps the film's most dramatic display of corrupt power, the Zubrowkan military invasion of the Grand Budapest, and the fascist emblems of the hotel lobby's newly adorned tapestry, mirror scenes from Leni Riefenstahl's propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935).[101] Gustave's black-and-white stripes evoke the uniforms of the concentration camp prisoners, and his steadfast commitment to his job becomes an act of defiance that threatens to jeopardize his life.[101] The Atlantic's Norman L. Eisen, who is among the people listed in "Special Thanks" at the end of the film, called The Grand Budapest Hotel a cautionary tale of the consequences of the Holocaust, a story that examines Nazi motivations while traversing postwar European history through comedy. He contends that certain main characters symbolize both the oppressed—the openly bisexual Gustave represents the LGBT community, the refugee Zero represents nonwhite immigrants, and Kovacs represents ethnic Jews—and the oppressor in Dmitri, overseer of a fascist, SS-like organization.[91] Film critic Daniel Garrett argues Gustave defies fascist notions of human perfection because he embraces the flaws of his peers, despite his own expertise: "Gustave is not surprised by feelings of anxiety or desire, or contemptuous of a scarred or crippled body; and he shares his values with his staff, with Zero. Gustave sees the heart and the effort, the spirit, despite his regard for excellence, ritual, and style."[102]

Friendship and loyalty

[edit]Another principal topic of discussion among critics has been The Grand Budapest Hotel's exploration of friendship and loyalty. Indeed, Zero appears to be Gustave's only true friend, and his unwavering devotion (at first, a mentor-protégé relationship) establishes the film's strongest bond.[90][102] Gustave is underwhelmed by Zero but is increasingly empathetic to his newly hired mentee's plight in their subsequent exploits, united by their shared enthusiasm for the hotel—so much that he defends Zero against police thuggery and rewards his loyalty with his inheritance.[90][103] Zero's less-central romance with Agatha is as constant a presence as his friendship with Gustave; he continues operating the hotel in his dead lover's memory, despite the slain Gustave representing the Grand Budapest's spirit.[90] The subject matter's emphasis of love, friendship, and the intertwining tales of nobility, dignity, and self-control, The New Yorker's Richard Brody argues, forms the "very soul of a moral politics that transcends accidents of circumstance and particular historical incidents".[103]

Kornhaber contends the focus on the dynamic of a mismatched pairing forms the crux of The Grand Budapest Hotel's central theme.[104] The unusual circumstance of the Gustave–Zero friendship seems to reflect an attachment to "an idea of historical and cultural belonging that they find ultimately to be best expressed through one another", and by proxy, the two men discover a fundamental kinship through their shared esteem of the Grand Budapest.[104]

Color

[edit]The Grand Budapest Hotel's use of color accentuates narrative tones and conveys visual emphasis to the subject matter and passage of time. The film eschews Anderson's trademark pale yellow for a sharp palette of vibrant reds, pinks and purples in pre-war Grand Budapest scenes. The composition fades as the timeline forebodes impending war, sometimes in complete black-and-white in scenes exploring Zero's memory of wartime, underscoring the gradual tonal shift. Subdued beiges, orange, and pale blue characterize the visual palette of post-war Grand Budapest scenes, manifesting the hotel's diminished prestige.[90]

Marketing and release

[edit]

The Grand Budapest Hotel premiered in competition at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival on February 6, 2014, winning the fest's Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize.[105][106] The film was Anderson's third in competition at the festival.[107] It headlined the 10th Glasgow Film Festival as the event's opening film, held February 20 – March 2, 2014,[108] before hosting its North American premiere on February 27 at the Film at Lincoln Center in New York City.[109]

Fox Searchlight spearheaded the marketing campaign. Their strategy involved merchandise releases, a global publicity tour,[110] the creation of mock websites about Zubrowkan culture,[111] and trailers highlighting the cast's star power.[112] One of their most significant marketing tactics, instructional videos detailing the creation of desserts mirroring Mendl's baked goods, used fan footage submitted to the producers for TV-commercial spots on cooking networks.[110] In conjunction with their collaboration with Anderson, Prada showcased its capsule collection of custom luggage from in-store displays at the Berlin flagship store.[113]

The Grand Budapest Hotel was released in France on February 26, 2014, preceding the film's global rollout. General release expanded to Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the United States (March 7), and two other international markets the second week.[114] The Grand Budapest Hotel opened to a few US theaters as part of a month-long limited platform release, initially screening from four arthouse theaters in New York and Los Angeles.[109] After the 87th Academy Awards' nominations announcement, Fox re-expanded the film's theater presence for a brief, multi-city re-release campaign.[115]

Fox Searchlight released The Grand Budapest Hotel on DVD and Blu-ray on June 17, 2014.[116] The discs include behind-the-scenes footage with Murray, promotional shots, deleted scenes, and the theatrical trailer.[117] The Grand Budapest Hotel was the fourth-best selling film on DVD and Blu-ray in its first week of US sales, selling 92,196 copies and earning US$1.6 million.[118] By March 2015, the film had sold 551,639 copies.[119]

The Criterion Collection issued director-approved special edition Blu-ray and DVD releases of The Grand Budapest Hotel on April 28, 2020. The discs include audio commentary from Anderson, Goldblum, producer Roman Coppola, and film critic Kent Jones; storyboard animatics, a behind-the-scenes documentary, video essays, and previously unaired cast and crew interviews.[120]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Grand Budapest Hotel was considered a surprise box office success.[121] The film's performance plateaued in North America after a strong start, but finished the theatrical run as Anderson's highest-grossing film in the region.[122][123] It performed strongest in key European and Asian markets.[122][124] Germany was the most lucrative market, and the film's link to that country boosted the box office performance.[124] South Korea, Australia, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom represented some of the film's largest takings.[124] The Grand Budapest Hotel earned $59.3 million (34.3 percent of its earnings) in the United States and Canada and $113.7 million (65.7 percent) overseas, for a worldwide total of $173 million,[3] making it the 46th-highest-grossing film of 2014,[125] and Anderson's highest-grossing film to date.[126]

The film posted $2.8 million from 172 theaters during its opening week in France, trailing Supercondriaque and Non-Stop. In Paris, The Grand Budapest Hotel screenings were the weekend's biggest numbers.[114] The film's $16,220 per-theater average was the best opening for any Anderson-directed project in France to date.[109] In its second week the number of theaters grew to 192, and The Grand Budapest Hotel grossed another $1.64 million at the French box office.[127] Earnings dropped by just 30 percent the following weekend, for a total gross of $1.1 million.[128] By March 24, the box office posted a five percent increase, and The Grand Budapest Hotel's French release had taken $8.2 million overall.[129]

The week of March 6 saw The Grand Budapest Hotel take $6.2 million from 727 theaters internationally, yielding the most robust figures in Belgium ($156,000, from 12 theaters), Austria ($162,000, from 29 theaters), Germany ($1.138 million, from 163 theaters), and the United Kingdom (top-three debut, with £1.53 million or $1.85 million from 284 theaters).[127][130] It increased 11 percent in Germany the following weekend to $1.1 million,[128] and The Grand Budapest Hotel yielded $5.2 million from German cinemas by the week of March 31.[131] It sustained the box office momentum into the second week of UK general release with improved sales from an expanded theater presence, and by the third week, the film topped the national top ten with £1.27 million ($1.55 million) from 458 screens, buoyed by positive reviews in the media.[130] After a month it had earned $13.2 million in the UK.[131] The Grand Budapest Hotel's expansion to other overseas markets continued toward the end of March, marked by significant releases in Sweden (first place, with $498,108), Spain (third, with $1 million), and South Korea (the country's biggest specialty film opening ever, with $622,109 from 162 cinemas).[129] During its second week of release in South Korea, the film's box office ballooned by 70 percent to $996,000.[131] On its opening week elsewhere, The Grand Budapest Hotel earned $1.8 million in Australia, $382,000 in Brazil, and $1 million in Italy.[132][133] By May 27, the film's international gross exceeded $100 million.[134]

In the United States, The Grand Budapest Hotel opened to a $202,792-per theater average from a four-theater $811,166 overall gross, breaking the record for most robust live-action limited release previously held by Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master (2012).[135][136] The return, exceeding Fox's expectations for the weekend, was the best US opening for an Anderson-directed project to date.[135] The Grand Budapest Hotel also eclipsed Moonrise Kingdom's $130,749 per-theater average, hitherto Anderson's highest-opening limited release.[135] Fading interest in films hoping to capitalize on Academy Awards prestige and its crossover appeal to younger, casual moviegoers were crucial to The Grand Budapest Hotel's early box office success.[135] The film sustained the box office momentum as large suburban cineplexes were added to its limited run, racking $3.6 million the second week and $6.7 million the following weekend.[137][138] The film officially entered wide release the week of March 30 by screening in 977 theaters across North America.[139] New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Toronto, Washington, and Montreal were The Grand Budapest Hotel's most successful North American cities.[140] Its theater count peaked at 1,467 in mid-April before a gradual decline.[141] By the end of the month, the film's domestic gross topped $50 million.[142] The Grand Budapest Hotel ended its North American run on February 26, 2015.[143]

Critical response

[edit]Mr. Anderson is no realist. This movie makes a marvelous mockery of history, turning its horrors into a series of graceful jokes and mischievous gestures.

The Grand Budapest Hotel received widespread critical acclaim and various critics selected the film in their end-of-2014 lists.[144] Many of the reviews complimented The Grand Budapest Hotel for its craftsmanship, often singling out the film's zany sensibility and Anderson's expertise for further praise,[145][146][147] the latter for the creation of a fanciful onscreen world which does not take itself too seriously.[148][149] Occasionally, The Grand Budapest Hotel drew criticism for evading some of the harsh realities of the subject matter; according to a Vanity Fair reviewer, the film's devotion to a "kitschy adventure story that feels curiously weightless, at times even arbitrary" undermined any thoughtful moral.[150] The comic treatment of a madcap adventure was cited among the strengths of the film,[151][152][153] though sometimes the fragmented storytelling approach was considered a flaw by some critics, such as The New Yorker's David Denby, for following a sequence of events that seemed to lack emotional continuity.[95]

The actors' performances were routinely mentioned in the reviews. Journalists felt the ensemble brought The Grand Budapest Hotel ethos to life in comedic and dramatic moments,[148][154] particularly Ralph Fiennes,[155][156] whose performance was called "transformative" and "total perfection".[148][157] San Francisco Chronicle's Mick LaSalle felt Fiennes's casting was the study of a reserved actor exhibiting the fullest extent of his emotional range,[149] and Los Angeles Times's Kenneth Turan believed he exuded an "unbounded but carefully calibrated zeal", the only such actor capable of realizing Anderson's vision of a "will-o'-the-wisp world heft and reality while still being faithful to the singular spirit that underlies it".[148] On the other hand, characterization in The Grand Budapest Hotel drew varying responses from reviewers; Gustave, for example, was described as a man "of convincing feelings", "sweetly wistful",[148][158] but a protagonist lacking the depth of other prolific heroes in the Anderson canon, emblematic of a film that doesn't quite appear to fully flesh out the core cast of characters.[96]

As per the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 92% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 319 reviews, with an average rating of 8.40 out of 10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Typically stylish but deceptively thoughtful, The Grand Budapest Hotel finds Wes Anderson once again using ornate visual environments to explore deeply emotional ideas."[159] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 88 out of 100, with 94% positive reviews based on 48 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[160]

Accolades

[edit]The Grand Budapest Hotel was not an immediate favorite to dominate the 87th Academy Awards season. The film's early March opening was thought to deter any chance of Oscar recognition, for scheduling a fall release was the usual practice for studios positioning their films for awards attention.[161][162] The last spring season releases to achieve Best Picture success until then were Erin Brockovich (2000) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991).[162] A frontrunner had not emerged as the Academy Award nominations approached, partly as a result of a critical backlash against the season's biggest contenders, such as American Sniper, Selma and The Imitation Game.[162] Even so, US critics spread their honors for The Grand Budapest Hotel when compiling their end-of-year lists, and the film soon gained momentum thanks to a sustained presence in the award circuit.[162] Fox Searchlight president Nancy Utley attributed the film's ascendancy to its months-long presence on multimedia home entertainment platforms, which lent greater viewing opportunity for Academy voters.[161] At the Academy Award season, the film received nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography, and Best Film Editing; and won Best Original Score, Best Production Design, Best Makeup and Hairstyling, and Best Costume Design.[163]

The Grand Budapest Hotel was a candidate for other awards for excellence in writing, acting, directing, and technical achievement. It received nominations such as the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture and the César Award for Best Foreign Film.[162][164] The film's other wins include three Critics' Choice Movie Awards, five British Academy Film Awards, and a Golden Globe in the category of Best Motion Picture—Musical or Comedy.[165][166][167]

Legacy

[edit]Many viewed The Grand Budapest Hotel as Wes Anderson's magnum opus,[7] it appeared on professional rankings from BBC and IndieWire, based on retrospective appraisal, as one of the greatest films of the twenty-first century.[168][169] In December 2021, the film's screenplay was listed number twenty-five on the Writers Guild of America's "101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century (So Far)".[170]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Zubrowka is depicted as an alpine country located somewhere between Central and Eastern Europe. According to newspapers shown in the film, Zubrowka was a constitutional monarchy (the Empire of Zubrowka) at least until late 1932, when a neighboring fascist state annexed it during a period of war. In 1936, the country was liberated, and by 1950, it had become a socialist republic.[8][9] The opening titles introduce the region in 2014 as "The former Republic of Zubrowka, Once the seat of an Empire."

References

[edit]- ^ "The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)". British Film Institute (BFI). Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Grand Budapest Hotel". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 best films of the 21st century (So far)". February 6, 2022.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter; Clarke, Cath; Pulver, Andrew; Shoard, Catherine (September 13, 2019). "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian.

- ^ "The 87 Best Comedies of the 21st Century, from 'Neighbors' and 'Frances Ha' to 'Jackass Forever' and 'Borat'". November 29, 2023.

- ^ a b "'The Grand Budapest Hotel' is Wes Anderson's magnum opus". faroutmagazine.co.uk. March 7, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ "Newspapers & documents from "The Grand Budapest Hotel"". imgur.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 5. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Graphic Design for the Film". www.lilianalambriev.com. November 13, 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Meenan, David (October 29, 2022). "The Grand Budapest Hotel Ending Explained: An Enchanting Old Ruin". /Film. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ Oselund, R. Kurt (March 8, 2014). "Wes Anderson on Using Throwback Ratios, Romantic Worldviews, and European Reconnaissance to Craft The Grand Budapest Hotel". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on September 17, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 31

- ^ a b Weintraub, Steve (February 24, 2014). "Wes Anderson Talks The Grand Budapest Hotel, the Film's Cast, His Aesthetic, Shifting Aspect Ratios, and More". Collider. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stern, Marlow (March 4, 2014). "Wes Anderson Takes Us Inside 'The Grand Budapest Hotel,' His Most Exquisite Film". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 17, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Prochnik, George (March 8, 2014). "'I stole from Stefan Zweig': Wes Anderson on the author who inspired his latest movie". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo (March 5, 2014). "Interview: Wes Anderson On 'The Grand Budapest Hotel,' Elliott Smith, The Beatles, Owen Wilson, Westerns & More". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein, Paula (January 4, 2015). "Wes Anderson's DP Robert Yeoman". Indiewire. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 32

- ^ Gross, Terry (March 12, 2014). "Wes Anderson: 'We Made A Pastiche' Of Eastern Europe's Greatest Hits". NPR. Archived from the original on September 16, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Edelbaum, Susannah (February 20, 2018). "2018: Storyboard Artist Jay Clarke on Drawing Wes Anderson's Canine Showstopper Isle of Dogs". Motion Picture Association. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Seitz 2015, p. 102

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (October 16, 2013). "Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel' to Hit Theaters in Spring". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Strassberg, Rebecca (December 26, 2014). "11 Actors in Wes Anderson's Troupe". Backstage. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Staff (March 2014). "Edward Norton talks all things Wes Anderson and The Grand Budapest Hotel". Entertainment.ie. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Pape, Stefan (March 7, 2014). "The HeyUGuys Interview: Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum and Willem Dafoe on The Grand Budapest Hotel". HeyUGuys. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Siegel, Miranda (February 6, 2014). "Wes Anderson, Bill Murray, and Tilda Swinton Explain The Grand Budapest Hotel". New York. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Needham, Adam (March 2, 2014). "Adrien Brody: life after the Oscar". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Barlow, Helen (April 10, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel: Wes Anderson interview". Special Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (October 9, 2012). "Ralph Fiennes in Talks for Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Itzkoff, Dave (February 28, 2014). "Casting Shadows on a Fanciful World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Seitz 2015, p. 67

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 72

- ^ Crow, David (March 5, 2014). "Grand Budapest Hotel Interview with Ralph Fiennes and Tony Revolori". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Dawes, Amy (November 25, 2014). "The Envelope: Ralph Fiennes on nostalgia, heart in Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Mike (September 29, 2012). "Johnny Depp & 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'? Wes Anderson Says Actor Is Not In The Movie". HuffPost. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c Rich, Katey (February 21, 2015). "How The Grand Budapest Hotel Cast Its Most Challenging Role". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 42

- ^ Zuckermann, Esther (March 5, 2014). "Tony Revolori of 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' on Perfecting His Mustache". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Abraham, F. Murray (February 25, 2014). The Grand Budapest Hotel Interview—F. Murray Abraham (2014) (Press interview). Fandango. Event occurs at 1:57–2:00.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (November 2, 2012). "Saoirse Ronan to star in 'Budapest Hotel'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Butler, Karen (January 25, 2015). "Saoirse Ronan: 'Grand Budapest' director Wes Anderson was 'very secure in his vision'". United Press International. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Crow, David (March 6, 2014). "Interview with Saoirse Ronan and Adrien Brody On The Grand Budapest Hotel". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stasukevich, Iain (March 2014). "5-Star Service". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ Mulcahey, Matt (April 8, 2015). ""I Don't Want to Sound Negative About Digital": DP Robert Yeoman on NAB Show, The Grand Budapest Hotel and Shooting Film". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Roxborough, Scott (January 14, 2013). "Wes Anderson Starts Shoot for 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' in Berlin". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Seymour, Tom (March 4, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel: the kid stays in the picture". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Lang, Brent (April 8, 2014). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' Cracks German Financing, While Crafting Dazzling VFX". TheWrap. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (July 4, 2014). "Germany Cuts Funding (Again) for Film Tax Incentive". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 105

- ^ a b c McPherson, Angie (March 27, 2014). "Spoiler Alert: You Can't Really Stay at the Real Grand Budapest Hotel (But We Can Tell You Everything About It)". National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ White, Adam (January 9, 2018). "How to make a Wes Anderson movie, by his trusted cinematographer Robert Yeoman". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (February 5, 2014). "Berlin: How Wes Anderson Discovered His Grand Budapest Hotel". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Seitz 2015, p. 143

- ^ "GMA debuts P63-million state-of-the-art news set, technology for election coverage". BusinessMirror. May 8, 2019. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Laskin, Nicholas (September 9, 2015). "Watch: Video Essay Explores The Impact Of Different Aspect Ratios In Film". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 213

- ^ Haglund, David; Harris, Aisha (March 6, 2014). "The Aspect Ratios of The Grand Budapest Hotel". Slate. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g CGSociety staff (March 13, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel". CGSociety. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Enhancing color at ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 151

- ^ Chung, Becky (February 9, 2015). "We Talked to 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' Production Designer About Pastries, Postcards, and Taxidermy". Vice. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Seitz 2015, p. 163

- ^ a b c d e Edwards, Graham (March 11, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel". Cinefex. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Mekado (February 28, 2014). "You Can Look, but You Can't Check In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ "How a Viennese author inspired The Grand Budapest Hotel". Dazed. February 27, 2014. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ "Wes Anderson im Interview: Die Deutsche Bahn hat die besten Schlafwagen". Stern. March 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Meslow, Scott (April 2, 2014). "The untold story behind The Grand Budapest Hotel's "Boy with Apple"". The Week. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Staff (March 2, 2014). "Michael Taylor's painting Boy with Apple to play a central role in Wes Anderson's new film, The Grand Budapest Hotel". Waterhouse and Dodd. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Woodward, Adam (February 22, 2021). "The story behind The Grand Budapest Hotel's 'Boy with Apple' painting". Little White Lies. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ Wes Anderson Art Show Inspires Painting In Wes Anderson's New Film

- ^ Wes Anderson on The Grand Budapest Hotel, Reimagined Nazis, and His Sock Drawer

- ^ a b c "Designing for The Grand Budapest Hotel". Creative Review. March 11, 2014. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2020.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Rhodes, Margaret (March 14, 2014). "The Real Star Of Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"? Graphic Design". Fast Company. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Anderson, L. V. (March 19, 2014). "What It's Like to Bake Like Wes Anderson". Slate. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Sanders, Rachel (March 12, 2014). "How To Make The Starring Pastry From Wes Anderson's New Movie". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ a b Rado, Priya (March 7, 2014). "Behind the Fashion in The Grand Budapest Hotel". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Seitz 2015, p. 89

- ^ a b c d Kinosian, Janet (December 4, 2014). "The Envelope: Milena Canonero's 'Grand Budapest' costumes match Wes Anderson's vision". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Seitz 2015, p. 90

- ^ Rich, Katey (February 13, 2015). "How to Turn Tilda Swinton Into an Old Lady, With Enough Liver Spots to Make Wes Anderson Happy". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (February 26, 2014). "Stream Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel Soundtrack". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Danton, Eric R. (February 18, 2014). "Grand Budapest Hotel Soundtrack Relies On Original Music (Song Premiere)". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Jagernauth, Kevin (June 19, 2014). "Exclusive: Pics Of Recording Sessions For 'Grand Budapest Hotel,' Randall Poster Talks Score, Wes Anderson & More". Indiewire. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Lacombe, Bridgette (December 4, 2014). "Interview with Alexandre Desplat". Film Music. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Seitz 2015, pp. 135–136

- ^ Davis, Edward (January 23, 2014). "Alexandre Desplat & More: Wes Anderson's 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' Soundtrack Arrives On March 4th". Indiewire. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (February 19, 2015). "Composing The Folk Music Of A Made-Up Country". NPR. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Stream Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel Soundtrack on Pitchfork Advance". Pitchfork. February 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Giroux, Jack (March 6, 2014). "How Wes Anderson Built 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Marshall, Lee (Summer 2014). "The Budapest Hotel: Wes Anderson's Fabulous Fancy". Queen's Quarterly. Vol. 121. Kingston, Ontario. pp. 242–251.

- ^ a b Eisen, Norman (February 20, 2015). "The Grand Budapest Hotel Is a Thoughtful Comedy About Tragedy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Scott, A.O. (March 6, 2014). "Bittersweet Chocolate on the Pillow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Dilley 2017, p. 29

- ^ Levitz, Eric (April 3, 2014). "Up in the old hotel: The hidden meaning of Wes Anderson's nostalgia". Salon. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Denby, David (March 3, 2014). "Lost Time". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Dowd, A.A. (March 6, 2014). "Wes Anderson erects The Grand Budapest Hotel, a delightfully madcap caper · Movie Review". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Dilley 2017, p. 463

- ^ Jenkins, David (March 6, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel". Little White Lies. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Kornhaber 2017, pp. 250–251

- ^ Suebsaeng, Asawin (March 14, 2014). "The Whimsical Fascists of Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Adams, Sam (March 7, 2014). ""The Grand Budapest Hotel" Isn't (Just) Wes Anderson's Best Movie: It's a Breakthrough". Indiewire. Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Garrett, Daniel (November 2016). "Charm, Courage, and Eruptions of Vulgar Force: Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel". Offscreen. Vol. 20. Canada. ISSN 1712-9559.

- ^ a b Brody, Richard (March 7, 2014). ""The Grand Budapest Hotel": Wes Anderson's Artistic Manifesto". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Kornhaber 2017, pp. 253–254

- ^ "Prizes of the International Jury". Berlin International Film Festival. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ Mesa, Ed (February 15, 2014). "Berlin Golden Bear Goes to China's 'Black Coal, Thin Ice,' Jury Prize to 'Grand Budapest Hotel'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (November 5, 2013). "Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel' To Open Berlin Film Festival In World Premiere". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (January 21, 2014). "Wes Anderson's 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' to Open Glasgow Film Festival". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Brian (March 6, 2014). "Specialty B.O. Preview: 'The Grand Budapest Hotel', 'Grand Piano', 'Journey To The West: Conquering The Demons', 'Miele', 'Particle Fever', 'Bethlehem'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Stewart, Andrew (April 10, 2014). "Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel': 5 Ways Marketing Was Key". Variety. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Staff. "Grand Budapest Hotel's rolls out quirky content". Lürzer's Archive. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017.

- ^ Staff (October 17, 2013). "Hot Trailer: 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (February 7, 2014). "Prada Celebrates Wes Anderson 'Grand' Collaboration With Berlin Display". Variety. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Tartaglione, Nancy (March 3, 2014). "Update: International Box Office: 'The Hobbit: The Desolation Of Smaug' Has No. 1 Japan Opening; 'Lego' Builds to $121M Overseas; 'Frozen' Crossing $1B Worldwide; 'Robocop' Takes $20.5M In China; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (January 16, 2015). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' Checks Back Into Theaters After Oscar Nom Haul". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Strowbridge, C.S. (June 17, 2014). "DVD and Blu-ray Releases for June 17th, 2014". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Bowen, Chuck (June 18, 2014). "Blu-ray Review: The Grand Budapest Hotel". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ "United States Combined DVD and Blu-ray Sales Chart for Week Ending June 22, 2014". The Numbers. June 22, 2014. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ "The Grand Budapest Hotel". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "The Grand Budapest Hotel". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Olsen, Mark (March 23, 2014). "Wes Anderson's 'Grand Budapest Hotel' builds at the box office". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (April 16, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel becomes Wes Anderson's highest-grossing film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (January 9, 2015). "'The Grand Budapest Hotel' Tops Specialty B.O.'s Top 10 For 2014". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cunningham, Todd (April 4, 2014). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' Clicks at Box Office in Germany, Where It Was Filmed". TheWrap. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ "2014 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Maane (April 14, 2014). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' Hits $100 Mil, Becomes Wes Anderson's Highest-Grossing Pic". Variety. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Tartaglione, Nancy (March 10, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: '300: Rise Of An Empire' Lifts To $88.8M; 'Non-Stop' Passes $100M Worldwide; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Tartaglione, Nancy (March 17, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: 'Rise Of An Empire' Cumes $159.6M; Universal's Spanish Comedy Breaks Records; 'Need For Speed' China Haul Outpaces Domestic; 'Frozen' Hot In Japan; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Tartaglione, Nancy (March 24, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: 'Need For Speed' Adds $29.2M For No. 1; 'Noah' Reigns In Mexico & Korea With $14M; 'Peabody & Sherman' Crosses $100M; 'Spanish Affairs' Muy Caliente; Asian Pics Advance; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Grant, Charles (March 26, 2014). "Grand Budapest Hotel overtakes Need for Speed to cruise into top spot". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Tartaglione, Nancy (March 31, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: 'Captain America: The Winter Soldier' Captures $75.2M; 'Noah' Swells To $51.5M Cume; 'Rio 2' Breaks Brazil Records; 'Lego' Passes $400M; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (April 14, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: 'Rio 2' Soars With $63.4M; 'Captain America: The Winter Soldier' Blasts Past $300M Overseas; 'Noah' Adds $36.2M; 'Divergent' Nearing $50M". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (July 8, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: 'Transformers' Adds $52M In China Weekend; 'Dragon 2' Fires Up $30M; And How's 'Tammy'?; 'Maleficent' Dethrones 'Frozen' In Japan; More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (May 27, 2014). "Update: Intl Box Office: Fan-Tastic 'X-Men' Bows To Biggest Fox Opener Ever And No. 1 In Every Market; 'Godzilla' Second Weekend Pushes WB To $1B 2014; 'Blended' Rolls Out Slowly; 'Neighbors' Still Partying, More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Brooks, Brian (March 9, 2014). "Box Office: 'Grand Budapest Hotel' Checks In With Record Per-Screen Average". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Busch, Anita (March 10, 2014). "Box Office Final: '300: Rise Of An Empire' Commands $45M; 'Mr. Peabody' Chases In $32.2M; 'Son Of God' Falls 59% In Second Weekend, 'Budapest Hotel' Per Screen Stuns With Over $202K". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (March 16, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: 'Grand Budapest Hotel' Checks In With Lofty $55K PTA In Expansion; Bateman's 'Bad Words' Solid". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (March 23, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: 'Grand Budapest' Extends Reign In Expansion; 'Nymphomaniac' Bows So-So Theatrically". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (March 30, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: 'Raid 2', 'Finding Vivian Maier' Start Solid, 'Cesar Chavez' Posts Middling Results". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (April 6, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: Scarlett Johansson Reigns With Sci-Fier 'Under The Skin'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (April 20, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: 'Fading Gigolo' Seduces In Limited Opening; 'Under The Skin' Passes $1M". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Brian (May 4, 2014). "Specialty Box Office: 'Belle' Is A Potent Lady; 'Ida' Shows Traction; 'Walk Of Shame' Tiptoes Into Limited Release". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Grand Budapest Hotel". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Dietz, Jason (December 6, 2014). "Best of 2014: Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (February 6, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Howell, Peter. "The Grand Budapest Hotel a delicious cinema cake: Review". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Whitty, Stephen (March 7, 2014). "'The Grand Budapest Hotel' review: No reservations". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Turan, Kenneth (March 6, 2014). "Review: Wes Anderson makes 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' a four-star delight". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ a b LaSalle, Mick (March 13, 2014). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' review: Wes Anderson at his best". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Lawson, Richard (March 5, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel Is a Too-Quick Trip to a Lovely Place". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Chang, Justin (February 6, 2014). "Berlin Film Review: 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'". Variety. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Hines, Nico (February 6, 2014). "'The Grand Budapest Hotel' Review: Wes Anderson's Best Ever Is a Whimsical Crime Caper". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Esfahani, Emily (March 14, 2014). "The Sober Frivolity of The Grand Budapest Hotel". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (March 13, 2014). "Review: 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Rea, Steven (March 14, 2014). "Anderson at his best in 'Grand Budapest Hotel'". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (March 20, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel Movie Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Neumaier, Joe (March 6, 2014). "'The Grand Budapest Hotel': Movie review". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Macdonald, Moira (March 13, 2014). "The Grand Budapest Hotel: It's a trip". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ "THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on August 27, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ "The Grand Budapest Hotel". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Lang, Brent (January 15, 2015). "How 'Grand Budapest Hotel' Became a Surprise Oscars Powerhouse". Variety. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Hammond, Pete (January 2, 2015). "Oscars: How 'The Grand Budapest Hotel' Could Turn Awards Season On Its Head". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Oscars 2015: The Winners List". The Hollywood Reporter. February 22, 2015. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (January 28, 2015). "César Nominations: 'Saint Laurent', 'Timbuktu', Kristen Stewart In Mix—Full List". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Critics' Choice Awards: The Winners". The Hollywood Reporter. January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Ritman, Alex; Szalai, Georg (February 8, 2015). "BAFTA Awards: 'Boyhood' Wins Best Film, 'Grand Budapest Hotel' Gets Five Honors". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Golden Globes: The Complete Winners List". The Hollywood Reporter. January 11, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 19, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ Dry, Jude; O'Falt, Chris; Erbland, Kate; Kohn, Eric; Sharf, Zack; Marotta, Jenna; Thompson, Anne; Earl, William; Nordine, Michael; Ehrlich, David (April 20, 2018). "The 25 Best American Screenplays of the 21st Century, From 'Eternal Sunshine' to 'Lady Bird'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Pedersen, Erik (December 6, 2021). "101 Greatest Screenplays Of The 21st Century: Horror Pic Tops Writers Guild's List". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

Bibliography