GIF

An animated GIF of a rotating globe | |

| Filename extension | .gif |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | image/gif |

| Type code | GIFf |

| Uniform Type Identifier (UTI) | com.compuserve.gif |

| Magic number | GIF87a/GIF89a |

| Developed by | CompuServe |

| Initial release | 15 June 1987[1] |

| Latest release | 89a 1989[2] |

| Type of format | lossless bitmap image format |

| Website | www |

The Graphics Interchange Format (GIF; /ɡɪf/ GHIF or /dʒɪf/ JIF, ) is a bitmap image format that was developed by a team at the online services provider CompuServe led by American computer scientist Steve Wilhite and released on June 15, 1987.[1]

The format can contain up to 8 bits per pixel, allowing a single image to reference its own palette of up to 256 different colors chosen from the 24-bit RGB color space. It can also represent multiple images in a file, which can be used for animations, and allows a separate palette of up to 256 colors for each frame. These palette limitations make GIF less suitable for reproducing color photographs and other images with color gradients but well-suited for simpler images such as graphics or logos with solid areas of color.

GIF images are compressed using the Lempel–Ziv–Welch (LZW) lossless data compression technique to reduce the file size without degrading the visual quality.

While once in widespread usage on the World Wide Web because of its wide implementation and portability between applications and operating systems, usage of the format has declined for space and quality reasons, often being replaced with video formats such as the MP4 file format. These replacements, in turn, are sometimes termed "GIFs" despite having no relation to the original file format.[3]

History

[edit]

CompuServe introduced GIF on 15 June 1987 to provide a color image format for their file downloading areas. This replaced their earlier run-length encoding format, which was black and white only. GIF became popular because it used Lempel–Ziv–Welch data compression. Since this was more efficient than the run-length encoding used by PCX and MacPaint, fairly large images could be downloaded reasonably quickly even with slow modems.

The original version of GIF was called 87a.[1] This version already supported multiple images in a stream.

In 1989, CompuServe released an enhanced version, called 89a,[2] This version added:

- support for animation delays

- transparent background colors

- storage of application-specific metadata

- allowing text labels as text (not embedding them in the graphical data). As there is little control over display fonts, however, this feature is rarely used.

The two versions can be distinguished by looking at the first six bytes of the file (the "magic number" or signature), which, when interpreted as ASCII, read "GIF87a" or "GIF89a", respectively.

CompuServe encouraged the adoption of GIF by providing downloadable conversion utilities for many computers. By December 1987, for example, an Apple IIGS user could view pictures created on an Atari ST or Commodore 64.[4] GIF was one of the first two image formats commonly used on Web sites, the other being the black-and-white XBM.[5]

In September 1995 Netscape Navigator 2.0 added the ability for animated GIFs to loop.

While GIF was developed by CompuServe, it used the Lempel–Ziv–Welch (LZW) lossless data compression algorithm patented by Unisys in 1985. Controversy over the licensing agreement between Unisys and CompuServe in 1994 spurred the development of the Portable Network Graphics (PNG) standard. In 2004, all patents relating to the proprietary compression used for GIF expired.

The feature of storing multiple images in one file, accompanied by control data, is used extensively on the Web to produce simple animations.

The optional interlacing feature, which stores image scan lines out of order in such a fashion that even a partially downloaded image was somewhat recognizable, also helped GIF's popularity,[6] as a user could abort the download if it was not what was required.

In May 2015 Facebook added support for GIF.[7][8] In January 2018 Instagram also added GIF stickers to the story mode.[9]

In 2016 the Internet Archive released a searchable library of GIFs from their Geocities archive.[10][11]

Terminology

[edit]As a noun, the word GIF is found in the newer editions of many dictionaries. In 2012, the American wing of the Oxford University Press recognized GIF as a verb as well, meaning "to create a GIF file", as in "GIFing was the perfect medium for sharing scenes from the Summer Olympics". The press's lexicographers voted it their word of the year, saying that GIFs have evolved into "a tool with serious applications including research and journalism".[12][13]

Pronunciation

[edit]

The pronunciation of the first letter of GIF has been disputed since the 1990s. The most common pronunciations in English are /dʒɪf/ (with a soft g as in gin) and /ɡɪf/ (with a hard g as in gift), differing in the phoneme represented by the letter G. The creators of the format pronounced the acronym GIF as /dʒɪf/, with a soft g, with Wilhite stating that he intended for the pronunciation to deliberately echo the American peanut butter brand Jif, and CompuServe employees would often quip "choosy developers choose GIF", a spoof of Jif's television commercials.[14] However, the word is widely pronounced as /ɡɪf/, with a hard g,[15] and polls have generally shown that this hard g pronunciation is more prevalent.[16][17]

Dictionary.com[18] cites both pronunciations, indicating /dʒɪf/ as the primary pronunciation, while Cambridge Dictionary of American English[19] offers only the hard-g pronunciation. Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary[20] and Oxford Dictionaries cite both pronunciations, but place the hard g first: /ɡɪf, dʒɪf/.[21][22][23][24] The New Oxford American Dictionary gave only /dʒɪf/ in its second edition[25] but updated it to /dʒɪf, ɡɪf/ in the third edition.[26]

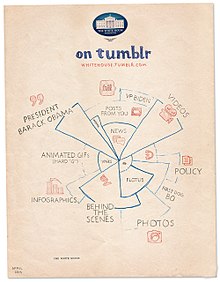

The disagreement over the pronunciation has led to heated Internet debate. On the occasion of receiving a lifetime achievement award at the 2013 Webby Awards ceremony, Wilhite publicly rejected the hard-g pronunciation;[15][27][28] his speech led to more than 17,000 posts on Twitter and dozens of news articles.[29] The White House[15] and the TV program Jeopardy! also entered the debate in 2013.[28] In February 2020, The J.M. Smucker Company, the owners of the Jif brand, partnered with the animated image database and search engine Giphy to release a limited-edition "Jif vs. GIF" (hashtagged as #JIFvsGIF) jar of peanut butter that had a label humorously declaring the soft-g pronunciation to refer exclusively to the peanut butter, and GIF to be exclusively pronounced with the hard-g pronunciation.[30]

Usage

[edit]GIFs are suitable for sharp-edged line art with a limited number of colors, such as logos. This takes advantage of the format's lossless compression, which favors flat areas of uniform color with well defined edges.[31] They can also be used to store low-color sprite data for games.[32] GIFs can be used for small animations and low-resolution video clips, or as reactions in online messaging used to convey emotion and feelings instead of using words. They are popular on social media platforms such as Tumblr,[33] Facebook and Twitter.[34]

File format

[edit]Conceptually, a GIF file describes a fixed-sized graphical area (the "logical screen") populated with zero or more "images". Many GIF files have a single image that fills the entire logical screen. Others divide the logical screen into separate sub-images. The images may also function as animation frames in an animated GIF file, but again these need not fill the entire logical screen.

GIF files start with a fixed-length header ("GIF87a" or "GIF89a") giving the version, followed by a fixed-length Logical Screen Descriptor giving the pixel dimensions and other characteristics of the logical screen. The screen descriptor may also specify the presence and size of a Global Color Table (GCT), which follows next if present.

Thereafter, the file is divided into segments of the following types, each introduced by a 1-byte sentinel:

- An image (introduced by 0x2C, an ASCII comma

',') - An extension block (introduced by 0x21, an ASCII exclamation point

'!') - The trailer (a single byte of value 0x3B, an ASCII semicolon

';'), which should be the last byte of the file.

An image starts with a fixed-length Image Descriptor, which may specify the presence and size of a Local Color Table (which follows next if present). The image data follows: one byte giving the bit width of the unencoded symbols (which must be at least 2 bits wide, even for bi-color images), followed by a series of sub-blocks containing the LZW-encoded data.

Extension blocks (blocks that "extend" the 87a definition via a mechanism already defined in the 87a spec) consist of the sentinel, an additional byte specifying the type of extension, and a series of sub-blocks with the extension data. Extension blocks that modify an image (like the Graphic Control Extension that specifies the optional animation delay time and optional transparent background color) must immediately precede the segment with the image they refer to.

Each sub-block begins with a byte giving the number of subsequent data bytes in the sub-block (1 to 255). The series of sub-blocks is terminated by an empty sub-block (a 0 byte).

This structure allows the file to be parsed even if not all parts are understood. A GIF marked 87a may contain extension blocks; the intent is that a decoder can read and display the file without the features covered in extensions it does not understand.

The full detail of the file format is covered in the GIF specification.[2]

Palettes

[edit]

GIF is palette-based: the colors used in an image (a frame) in the file have their RGB values defined in a palette table that can hold up to 256 entries, and the data for the image refer to the colors by their indices (0–255) in the palette table. The color definitions in the palette can be drawn from a color space of millions of shades (224 shades, 8 bits for each primary), but the maximum number of colors a frame can use is 256. This limitation was reasonable when GIF was developed because hardware that could display more than 256 colors simultaneously was rare. Simple graphics, line drawings, cartoons, and grey-scale photographs typically need fewer than 256 colors.

Each frame can designate one index as a "transparent background color": any pixel assigned this index takes on the color of the pixel in the same position from the background, which may have been determined by a previous frame of animation.

Many techniques, collectively called dithering, have been developed to approximate a wider range of colors with a small color palette by using pixels of two or more colors to approximate in-between colors. These techniques sacrifice spatial resolution to approximate deeper color resolution. While not part of the GIF specification, dithering can be used in images subsequently encoded as GIF images. This is often not an ideal solution for GIF images, both because the loss of spatial resolution typically makes an image look fuzzy on the screen, and because the dithering patterns often interfere with the compressibility of the image data, working against GIF's main purpose.

In the early days of graphical web browsers[when?], graphics cards with 8-bit buffers (allowing only 256 colors) were common and it was fairly common to make GIF images using the websafe palette.[according to whom?] This ensured predictable display, but severely limited the choice of colors. When 24-bit color became the norm, palettes could instead be populated with the optimum colors for individual images.

A small color table may suffice for small images, and keeping the color table small allows the file to be downloaded faster. Both the 87a and 89a specifications allow color tables of 2n colors for any n from 1 through 8. Most graphics applications will read and display GIF images with any of these table sizes; but some do not support all sizes when creating images. Tables of 2, 16, and 256 colors are widely supported.

True color

[edit]Although GIF is almost never used for true color images, it is possible to do so.[35][36] A GIF image can include multiple image blocks, each of which can have its own 256-color palette, and the blocks can be tiled to create a complete image. Alternatively, the GIF89a specification introduced the idea of a "transparent" color where each image block can include its own palette of 255 visible colors plus one transparent color. A complete image can be created by layering image blocks with the visible portion of each layer showing through the transparent portions of the layers above.

To render a full-color image as a GIF, the original image must be broken down into smaller regions having no more than 255 or 256 different colors. Each of these regions is then stored as a separate image block with its own local palette and when the image blocks are displayed together (either by tiling or by layering partially transparent image blocks), the complete, full-color image appears. For example, breaking an image into tiles of 16 by 16 pixels (256 pixels in total) ensures that no tile has more than the local palette limit of 256 colors, although larger tiles may be used and similar colors merged resulting in some loss of color information.[35]

Since each image block can have its own local color table, a GIF file having many image blocks can be very large, limiting the usefulness of full-color GIFs.[36] Additionally, not all GIF rendering programs handle tiled or layered images correctly. Many rendering programs interpret tiles or layers as animation frames and display them in sequence as an animation[35] with most web browsers automatically displaying the frames with a delay time of 0.1 seconds or more.[37][38][better source needed]

Example GIF file

[edit]| Microsoft Paint saves a small black-and-white image as the following GIF file (illustrated enlarged). Paint does not make optimal use of GIF; due to the unnecessarily large color table (storing a full 256 colors instead of the used 2) and symbol width, this GIF file is not an efficient representation of the 15-pixel image. Although the Graphic Control Extension block declares color index 16 (hexadecimal 10) to be transparent, that index is not used in the image. The only color indexes appearing in the image data are decimal 40 and 255, which the Global Color Table maps to black and white, respectively. |

Sample image (enlarged), actual size 3 pixels wide by 5 high |

The hex numbers in the following tables are in little-endian byte order, as the format specification prescribes.

Image coding

[edit]The image pixel data, scanned horizontally from top left, are converted by LZW encoding to codes that are then mapped into bytes for storing in the file. The pixel codes typically don't match the 8-bit size of the bytes, so the codes are packed into bytes by a "little-Endian" scheme: the least significant bit of the first code is stored in the least significant bit of the first byte, higher order bits of the code into higher order bits of the byte, spilling over into the low order bits of the next byte as necessary. Each subsequent code is stored starting at the least significant bit not already used.

This byte stream is stored in the file as a series of "sub-blocks". Each sub-block has a maximum length 255 bytes and is prefixed with a byte indicating the number of data bytes in the sub-block. The series of sub-blocks is terminated by an empty sub-block (a single 0 byte, indicating a sub-block with 0 data bytes).

For the sample image above the reversible mapping between 9-bit codes and bytes is shown below.

| 9-bit code | Byte | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexadecimal | Binary | Binary | Hexadecimal |

| 100 | 1 00000000 | 00000000 | 00 |

| 028 | 00 0101000 | 0101000 1 | 51 |

| 0FF | 011 111111 | 111111 00 | FC |

| 103 | 1000 00011 | 00011 011 | 1B |

| 102 | 10000 0010 | 0010 1000 | 28 |

| 103 | 100000 011 | 011 10000 | 70 |

| 106 | 1000001 10 | 10 100000 | A0 |

| 107 | 10000011 1 | 1 1000001 | C1 |

| 10000011 | 83 | ||

| 101 | 1 00000001 | 00000001 | 01 |

| 0000000 1 | 01 | ||

A slight compression is evident: pixel colors defined initially by 15 bytes are exactly represented by 12 code bytes including control codes. The encoding process that produces the 9-bit codes is shown below. A local string accumulates pixel color numbers from the palette, with no output action as long as the local string can be found in a code table. There is special treatment of the first two pixels that arrive before the table grows from its initial size by additions of strings. After each output code, the local string is initialized to the latest pixel color (that could not be included in the output code).

Table 9-bit

string --> code code Action

#0 | 000h Initialize root table of 9-bit codes

palette | :

colors | :

#255 | 0FFh

clr | 100h

end | 101h

| 100h Clear

Pixel Local |

color Palette string |

BLACK #40 28 | 028h 1st pixel always to output

WHITE #255 FF | String found in table

28 FF | 102h Always add 1st string to table

FF | Initialize local string

WHITE #255 FF FF | String not found in table

| 0FFh - output code for previous string

FF FF | 103h - add latest string to table

FF | - initialize local string

WHITE #255 FF FF | String found in table

BLACK #40 FF FF 28 | String not found in table

| 103h - output code for previous string

FF FF 28 | 104h - add latest string to table

28 | - initialize local string

WHITE #255 28 FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 28 FF FF | String not found in table

| 102h - output code for previous string

28 FF FF | 105h - add latest string to table

FF | - initialize local string

WHITE #255 FF FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 FF FF FF | String not found in table

| 103h - output code for previous string

FF FF FF | 106h - add latest string to table

FF | - initialize local string

WHITE #255 FF FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 FF FF FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 FF FF FF FF | String not found in table

| 106h - output code for previous string

FF FF FF FF| 107h - add latest string to table

FF | - initialize local string

WHITE #255 FF FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 FF FF FF | String found in table

WHITE #255 FF FF FF FF | String found in table

No more pixels

107h - output code for last string

101h End

For clarity the table is shown above as being built of strings of increasing length. That scheme can function but the table consumes an unpredictable amount of memory. Memory can be saved in practice by noting that each new string to be stored consists of a previously stored string augmented by one character. It is economical to store at each address only two words: an existing address and one character.

The LZW algorithm requires a search of the table for each pixel. A linear search through up to 4096 addresses would make the coding slow. In practice the codes can be stored in order of numerical value; this allows each search to be done by a SAR (Successive Approximation Register, as used in some ADCs), with only 12 magnitude comparisons. For this efficiency an extra table is needed to convert between codes and actual memory addresses; the extra table upkeeping is needed only when a new code is stored which happens at much less than pixel rate.

Image decoding

[edit]Decoding begins by mapping the stored bytes back to 9-bit codes. These are decoded to recover the pixel colors as shown below. A table identical to the one used in the encoder is built by adding strings by this rule:

| Yes | add string for local code followed by first byte of string for incoming code |

| No | add string for local code followed by copy of its own first byte |

shift

9-bit ----> Local Table Pixel

code code code --> string Palette color Action

100h 000h | #0 Initialize root table of 9-bit codes

: | palette

: | colors

0FFh | #255

100h | clr

101h | end

028h | #40 BLACK Decode 1st pixel

0FFh 028h | Incoming code found in table

| #255 WHITE - output string from table

102h | 28 FF - add to table

103h 0FFh | Incoming code not found in table

103h | FF FF - add to table

| - output string from table

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

102h 103h | Incoming code found in table

| - output string from table

| #40 BLACK

| #255 WHITE

104h | FF FF 28 - add to table

103h 102h | Incoming code found in table

| - output string from table

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

105h | 28 FF FF - add to table

106h 103h | Incoming code not found in table

106h | FF FF FF - add to table

| - output string from table

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

107h 106h | Incoming code not found in table

107h | FF FF FF FF - add to table

| - output string from table

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

| #255 WHITE

101h | End

LZW code lengths

[edit]Shorter code lengths can be used for palettes smaller than the 256 colors in the example. If the palette is only 64 colors (so color indexes are 6 bits wide), the symbols can range from 0 to 63, and the symbol width can be taken to be 6 bits, with codes starting at 7 bits. In fact, the symbol width need not match the palette size: as long as the values decoded are always less than the number of colors in the palette, the symbols can be any width from 2 to 8, and the palette size any power of 2 from 2 to 256. For example, if only the first four colors (values 0 to 3) of the palette are used, the symbols can be taken to be 2 bits wide with codes starting at 3 bits.

Conversely, the symbol width could be set at 8, even if only values 0 and 1 are used; these data would only require a two-color table. Although there would be no point in encoding the file that way, something similar typically happens for bi-color images: the minimum symbol width is 2, even if only values 0 and 1 are used.

The code table initially contains codes that are one bit longer than the symbol size in order to accommodate the two special codes clr and end and codes for strings that are added during the process. When the table is full the code length increases to give space for more strings, up to a maximum code 4095 = FFF(hex). As the decoder builds its table it tracks these increases in code length and it is able to unpack incoming bytes accordingly.

Uncompressed GIF

[edit]A 46×46 uncompressed GIF with 7-bit symbols (128 colors, 8-bit codes). |

The GIF encoding process can be modified to create a file without LZW compression that is still viewable as a GIF image. This technique was introduced originally as a way to avoid patent infringement. Uncompressed GIF can also be a useful intermediate format for a graphics programmer because individual pixels are accessible for reading or painting. An uncompressed GIF file can be converted to an ordinary GIF file simply by passing it through an image editor.

The modified encoding method ignores building the LZW table and emits only the root palette codes and the codes for CLEAR and STOP. This yields a simpler encoding (a 1-to-1 correspondence between code values and palette codes) but sacrifices all of the compression: each pixel in the image generates an output code indicating its color index. When processing an uncompressed GIF, a standard GIF decoder will not be prevented from writing strings to its dictionary table, but the code width must never increase since that triggers a different packing of bits to bytes.

If the symbol width is n, the codes of width n+1 fall naturally into two blocks: the lower block of 2n codes for coding single symbols, and the upper block of 2n codes that will be used by the decoder for sequences of length greater than one. Of that upper block, the first two codes are already taken: 2n for CLEAR and 2n + 1 for STOP. The decoder must also be prevented from using the last code in the upper block, 2n+1 − 1, because when the decoder fills that slot, it will increase the code width. Thus in the upper block there are 2n − 3 codes available to the decoder that won't trigger an increase in code width. Because the decoder is always one step behind in maintaining the table, it does not generate a table entry upon receiving the first code from the encoder, but will generate one for each succeeding code. Thus the encoder can generate 2n − 2 codes without triggering an increase in code width. Therefore, the encoder must emit extra CLEAR codes at intervals of 2n − 2 codes or less to make the decoder reset the coding dictionary. The GIF standard allows such extra CLEAR codes to be inserted in the image data at any time. The composite data stream is partitioned into sub-blocks that each carry from 1 to 255 bytes.

For the sample 3×5 image above, the following 9-bit codes represent "clear" (100) followed by image pixels in scan order and "stop" (101).

100 028 0FF 0FF 0FF 028 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 0FF 101

After the above codes are mapped to bytes, the uncompressed file differs from the compressed file thus:

| Byte # (hex) | Hexadecimal | Text or value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 320 | 14 | 20 | 20 bytes uncompressed image data follow |

| 321 | 00 51 FC FB F7 0F C5 BF 7F FF FE FD FB F7 EF DF BF 7F 01 01 | ||

| 335 | 00 | 0 | End of image data |

Compression example

[edit]The trivial example of a large image of solid color demonstrates the variable-length LZW compression used in GIF files.

| Code | Pixels | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.Ni | ValueNi + 256 | Length(bits) | This codeNi | AccumulatedNi(Ni + 1)/2 | Relations using Ni only apply to same-color pixels until coding table is full. |

| 0 | 100h | 9 | Clear code table | ||

| 1 | FFh | 1 | 1 | Top left pixel color chosen as the highest index of a 256-color palette | |

| 2 | 102h | 2 | 3 | ||

| 3⋮255 | 103h⋮1FFh | 3⋮255 | 6⋮32640 | Last 9-bit code | |

| 256⋮767 | 200h⋮3FFh | 10 | 256⋮767 | 32896⋮294528 | Last 10-bit code |

| 768⋮1791 | 400h⋮7FFh | 11 | 768⋮1791 | 295296⋮1604736 | Last 11-bit code |

| 1792⋮3839 | 800h⋮FFFh | 12 | 1792⋮3839 | 1606528⋮7370880 | Code table full |

| ⋮ | FFFh | 3839 | The maximum code may repeat for more same-color pixels.Overall data compression asymptotically approaches 3839 × 8/12 = 2559+1/3 | ||

| 101h | End of image data | ||||

The code values shown are packed into bytes which are then packed into blocks of up to 255 bytes. A block of image data begins with a byte that declares the number of bytes to follow. The last block of data for an image is marked by a zero block-length byte.

Interlacing

[edit]

The GIF Specification allows each image within the logical screen of a GIF file to specify that it is interlaced; i.e., that the order of the raster lines in its data block is not sequential. This allows a partial display of the image that can be recognized before the full image is painted.

An interlaced image is divided from top to bottom into strips 8 pixels high, and the rows of the image are presented in the following order:

- Pass 1: Line 0 (the top-most line) from each strip.

- Pass 2: Line 4 from each strip.

- Pass 3: Lines 2 and 6 from each strip.

- Pass 4: Lines 1, 3, 5, and 7 from each strip.

The pixels within each line are not interlaced, but presented consecutively from left to right. As with non-interlaced images, there is no break between the data for one line and the data for the next. The indicator that an image is interlaced is a bit set in the corresponding Image Descriptor block.

Animated GIF

[edit]

Although GIF was not designed as an animation medium, its ability to store multiple images in one file naturally suggested using the format to store the frames of an animation sequence. To facilitate displaying animations, the GIF89a spec added the Graphic Control Extension (GCE), which allows the images (frames) in the file to be painted with time delays, forming a video clip. Each frame in an animation GIF is introduced by its own GCE specifying the time delay to wait after the frame is drawn. Global information at the start of the file applies by default to all frames. The data is stream-oriented, so the file offset of the start of each GCE depends on the length of preceding data. Within each frame the LZW-coded image data is arranged in sub-blocks of up to 255 bytes; the size of each sub-block is declared by the byte that precedes it.

By default, an animation displays the sequence of frames only once, stopping when the last frame is displayed. To enable an animation to loop, Netscape in the 1990s used the Application Extension block (intended to allow vendors to add application-specific information to the GIF file) to implement the Netscape Application Block (NAB).[39] This block, placed immediately before the sequence of animation frames, specifies the number of times the sequence of frames should be played (1 to 65535 times) or that it should repeat continuously (zero indicates loop forever). Support for these repeating animations first appeared in Netscape Navigator version 2.0, and then spread to other browsers.[40] Most browsers now recognize and support NAB, though it is not strictly part of the GIF89a specification.

The following example shows the structure of the animation file Rotating earth (large).gif shown (as a thumbnail) in the article's infobox.

| Byte # (hex) | Hexadecimal | Text or value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 47 49 46 38 39 61 | GIF89a | Logical Screen Descriptor |

| 6 | 90 01 | 400 | Width in pixels |

| 8 | 90 01 | 400 | Height in pixels |

| A | F7 | GCT follows for 256 colors with resolution 3 × 8 bits/primary | |

| B | 00 | 0 | Background color: #000000, black |

| C | 00 | 0 | Default pixel aspect ratio, 0:0 |

| D | 00 | Global Color Table | |

| ⋮ | |||

| 30D | 21 | '!'

|

An Extension Block (introduced by an ASCII exclamation point '!')

|

| 30E | FF | Application Extension | |

| 30F | 0B | 11 | Size of block including application name and verification bytes (always 11) |

| 310 | 4E 45 54 53 43 41 50 45 32 2E 30 | NETSCAPE2.0 | 8-byte application name plus 3 verification bytes |

| 31B | 03 | 3 | Number of bytes in the following sub-block |

| 31C | 01 | 1 | Index of the current data sub-block (always 1 for the NETSCAPE block) |

| 31D | FF FF | 65535 | Unsigned number of repetitions |

| 31F | 00 | End of the sub-block chain for the Application Extension block | |

| 320 | 21 | '!'

|

An Extension Block (introduced by an ASCII exclamation point '!')

|

| 321 | F9 | Graphic Control Extension for frame #1 | |

| 322 | 04 | 4 | Number of bytes (4) in the current sub-block |

| 323 | 04 | 000.....

...001..

......0.

.......0

|

Reserved, 5 lower bits are bit field Disposal method 1: do not dispose No user input Transparent color, 0 means not given |

| 324 | 09 00 | 9 | Frame delay: 0.09 second delay before painting next frame |

| 326 | FF | Transparent color index (unused in this frame) | |

| 327 | 00 | End of sub-block chain for Graphic Control Extension block | |

| 328 | 2C | ',' |

An Image Descriptor (introduced by 0x2C, an ASCII comma ',')

|

| 329 | 00 00 00 00 | (0, 0) | North-west corner position of image in logical screen: (0, 0) |

| 32D | 90 01 90 01 | (400, 400) | Frame width and height: 400 × 400 pixels |

| 331 | 00 | 0 | Local color table: 0 means none & no interlacing |

| 332 | 08 | 8 | Minimum LZW code size for Image Data of frame #1 |

| 333 | FF | 255 | Number of bytes of LZW image data in the following sub-block: 255 bytes |

| 334 | ... | <image data> | Image data, 255 bytes |

| 433 | FF | 255 | Number of bytes of LZW image data in the following sub-block, 255 bytes |

| 434 | ... | <image data> | Image data, 255 bytes |

| ⋮ | Repeat for next blocks | ||

| 92C0 | 00 | End of sub-block chain for this frame | |

| 92C1 | 21 | '!'

|

An Extension Block (introduced by an ASCII exclamation point '!')

|

| 92C2 | F9 | Graphic Control Extension for frame #2 | |

| ⋮ | Repeat for next frames | ||

| EDABD | 21 | '!'

|

An Extension Block (introduced by an ASCII exclamation point '!')

|

| EDABE | F9 | Graphic Control Extension for frame #44 | |

| ⋮ | Image information and data for frame #44 | ||

| F48F5 | 3B | Trailer: Last byte in the file, signaling EOF |

The animation delay for each frame is specified in the GCE in hundredths of a second. Some economy of data is possible where a frame need only rewrite a portion of the pixels of the display, because the Image Descriptor can define a smaller rectangle to be rescanned instead of the whole image. Browsers or other displays that do not support animated GIFs typically show only the first frame.

The size and color quality of animated GIF files can vary significantly depending on the application used to create them. Strategies for minimizing file size include using a common global color table for all frames (rather than a complete local color table for each frame) and minimizing the number of pixels covered in successive frames (so that only the pixels that change from one frame to the next are included in the latter frame). More advanced techniques involve modifying color sequences to better match the existing LZW dictionary, a form of lossy compression. Simply packing a series of independent frame images into a composite animation tends to yield large file sizes. Tools are available to minimize the file size given an existing GIF.

Metadata

[edit]Metadata can be stored in GIF files as a comment block, a plain text block, or an application-specific application extension block. Several graphics editors use unofficial application extension blocks to include the data used to generate the image, so that it can be recovered for further editing.

All of these methods technically require the metadata to be broken into sub-blocks so that applications can navigate the metadata block without knowing its internal structure.

The Extensible Metadata Platform (XMP) metadata standard introduced an unofficial but now widespread "XMP Data" application extension block for including XMP data in GIF files.[41] Since the XMP data is encoded using UTF-8 without NUL characters, there are no 0 bytes in the data. Rather than break the data into formal sub-blocks, the extension block terminates with a "magic trailer" that routes any application treating the data as sub-blocks to a final 0 byte that terminates the sub-block chain.

Unisys and LZW patent enforcement

[edit]In 1977 and 1978, Jacob Ziv and Abraham Lempel published a pair of papers on a new class of lossless data-compression algorithms, now collectively referred to as LZ77 and LZ78. In 1983, Terry Welch developed a fast variant of LZ78 which was named Lempel–Ziv–Welch (LZW).[42][43]

Welch filed a patent application for the LZW method in June 1983. The resulting patent, US4558302,[44] granted in December 1985, was assigned to Sperry Corporation who subsequently merged with Burroughs Corporation in 1986 and formed Unisys.[42] Further patents were obtained in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and Canada.

In addition to the above patents, Welch's 1983 patent also includes citations to several other patents that influenced it, including:

- two 1980 Japanese patents from NEC's Jun Kanatsu,[45][46]

- U.S. patent 4,021,782 (1974) from John S. Hoerning,

- U.S. patent 4,366,551 (1977) from Klaus E. Holtz, and

- a 1981 German patent from Karl Eckhart Heinz.[47][48]

In June 1984, an article by Welch was published in the IEEE magazine which publicly described the LZW technique for the first time.[49] LZW became a popular data compression technique and, when the patent was granted, Unisys entered into licensing agreements with over a hundred companies.[42][50]

The popularity of LZW led CompuServe to choose it as the compression technique for their version of GIF, developed in 1987. At the time, CompuServe was not aware of the patent.[42] Unisys became aware that the version of GIF used the LZW compression technique and entered into licensing negotiations with CompuServe in January 1993. The subsequent agreement was announced on 24 December 1994.[43] Unisys stated that they expected all major commercial on-line information services companies employing the LZW patent to license the technology from Unisys at a reasonable rate, but that they would not require licensing, or fees to be paid, for non-commercial, non-profit GIF-based applications, including those for use on the on-line services.[50]

Following this announcement, there was widespread condemnation of CompuServe and Unisys, and many software developers threatened to stop using GIF. The PNG format (see below) was developed in 1995 as an intended replacement.[42][43][49] However, obtaining support from the makers of Web browsers and other software for the PNG format proved difficult and it was not possible to replace GIF, although PNG has gradually increased in popularity.[42] Therefore, GIF variations without LZW compression were developed. For instance the libungif library, based on Eric S. Raymond's giflib, allows creation of GIFs that followed the data format but avoided the compression features, thus avoiding use of the Unisys LZW patent.[51] A 2001 Dr. Dobb's article described a way to achieve LZW-compatible encoding without infringing on its patents.[52]

In August 1999, Unisys changed the details of their licensing practice, announcing the option for owners of certain non-commercial and private websites to obtain licenses on payment of a one-time license fee of $5000 or $7500.[53] Such licenses were not required for website owners or other GIF users who had used licensed software to generate GIFs. Nevertheless, Unisys was subjected to thousands of online attacks and abusive emails from users believing that they were going to be charged $5000 or sued for using GIFs on their websites.[54] Despite giving free licenses to hundreds of non-profit organizations, schools and governments, Unisys was completely unable to generate any good publicity and continued to be condemned by individuals and organizations such as the League for Programming Freedom who started the "Burn All GIFs" campaign in 1999.[55][56]

The United States LZW patent expired on 20 June 2003.[57] The counterpart patents in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy expired on 18 June 2004, the Japanese patents expired on 20 June 2004, and the Canadian patent expired on 7 July 2004.[57] Consequently, while Unisys has further patents and patent applications relating to improvements to the LZW technique,[57] LZW itself (and consequently GIF) have been free to use since July 2004.[58]

Alternatives

[edit]PNG

[edit]Portable Network Graphics (PNG) was designed as a replacement for GIF in order to avoid infringement of Unisys' patent on the LZW compression technique.[42] PNG offers better compression and more features than GIF,[59] animation being the only significant exception. PNG is more suitable than GIF in instances where true-color imaging and alpha transparency are required.

Although support for PNG format came slowly, new web browsers support PNG. Older versions of Internet Explorer do not support all features of PNG. Versions 6 and earlier do not support alpha channel transparency without using Microsoft-specific HTML extensions.[60] Gamma correction of PNG images was not supported before version 8, and the display of these images in earlier versions may have the wrong tint.[61]

For identical 8-bit (or lower) image data, PNG files are typically smaller than the equivalent GIFs, due to the more efficient compression techniques used in PNG encoding.[62] Complete support for GIF is complicated chiefly by the complex canvas structure it allows, though this is what enables the compact animation features.

Animation formats

[edit]Videos resolve many issues that GIFs present through common usage on the web. They include drastically smaller file sizes, the ability to surpass the 8-bit color restriction, and better frame-handling and compression through inter-frame coding. Virtually universal support for the GIF format in web browsers and a lack of official support for video in the HTML standard caused GIF to rise to prominence for the purpose of displaying short video-like files on the web.

- MNG ("Multiple-image Network Graphics") was originally developed as a PNG-based solution for animations. MNG reached version 1.0 in 2001, but few applications support it.

- APNG ("Animated Portable Network Graphics") was proposed by Mozilla in 2006. APNG is an extension to the PNG format as alternative to the MNG format. APNG is supported by most browsers as of 2019.[63] APNG provides the ability to animate PNG files, while retaining backwards compatibility in decoders that cannot understand the animation chunk (unlike MNG). Older decoders will simply render the first frame of the animation.

- The PNG group officially rejected APNG as an official extension on 20 April 2007.[64]

- There have been several subsequent proposals for a simple animated graphics format based on PNG using several different approaches.[65] Nevertheless, APNG is still under development by Mozilla and is supported in Firefox 3.0[66][67] while MNG support was dropped.[68][69] APNG is currently supported by all major web browsers including Chrome (since version 59.0), Opera, Firefox and Edge.

- Embedded Adobe Flash objects and MPEG files were used on some websites to display simple video, but required the use of an additional browser plugin.

- WebM and WebP are in development and are supported by some web browsers.[70]

- Other options for web animation include serving individual frames using AJAX, or animating SVG ("Scalable vector graphics") images using JavaScript or SMIL ("Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language").[71]

- With the introduction of widespread support of the HTML video (

<video>) tag in most web browsers, some websites use a looped version of the video tag generated by JavaScript functions. This gives the appearance of a GIF, but with the size and speed advantages of compressed video.

- Notable examples are Gfycat and Imgur and their GIFV metaformat, which is really a video tag playing a looped MP4 or WebM compressed video.[72]

- HEIF ("High Efficiency Image File Format") is an image file format, finalized in 2015, which uses a discrete cosine transform (DCT) lossy compression algorithm based on the HEVC video format, and related to the JPEG image format. In contrast to JPEG, HEIF supports animation.[73]

- Compared to the GIF format, which lacks DCT compression, HEIF allows significantly more efficient compression. HEIF stores more information and produces higher-quality animated images at a small fraction of an equivalent GIF's size.[74]

- VP9 only supports alpha compositing with 4:2:0 chroma subsampling,[75] which may be unsuitable for GIFs that combine transparency with rasterised vector graphics with fine color details.

- AV1 video codec or AVIF can also be used either as a video or a sequenced image.

Uses

[edit]In April 2014, 4chan added support for silent WebM videos that are under 3 MB in size and 2 min in length,[76][77] and in October 2014, Imgur started converting any GIF files uploaded to the site to H.264 video and giving the link to the HTML player the appearance of an actual file with a .gifv extension.[78][79]

In January 2016, Telegram started re-encoding all GIFs to MPEG-4 videos that "require up to 95% less disk space for the same image quality."[80]

See also

[edit]- AVIF

- Cinemagraph, a partially animated photograph often in GIF

- Clear GIF, a technique used to check content access

- Comparison of graphics file formats

- GIF art, a form of digital art associated with GIF

- GIFBuilder, early animated GIF creation program

- GNU plotutils (supports pseudo-GIF, which uses run-length encoding rather than LZW)

- Microsoft GIF Animator, historic program to create simple animated GIFs

- Software patent

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Graphics Interchange Format, Version 87a". W3C. 15 June 1987. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ a b c "Graphics Interchange Format, Version 89a". W3C. 31 July 1990. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Tiffany, Kaitlyn (7 October 2022). "The GIF Is on Its Deathbed". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Online Art". Compute!'s Apple Applications. December 1987. p. 10. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Holdener III, Anthony (2008). Ajax: The Definitive Guide: Interactive Applications for the Web. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0596528386.

- ^ Furht, Borko (2008). Encyclopedia of Multimedia. Springer. ISBN 978-0387747248.

- ^ McHugh, Molly (29 May 2015). "You Can Finally, Actually, Really, Truly Post GIFs on Facebook". Wired. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Perez, Sarah (29 May 2015). "Facebook Confirms It Will Officially Support GIFs". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Introducing GIF Stickers". Instagram. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ Ghoshal, Abhimanyu (28 October 2016). "Enjoy 1.6 million gloriously old-school GIFs from the GeoCities era". TNW | Shareables. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "GifCities". gifcities.org. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Oxford Dictionaries USA Word of the Year 2012". OxfordWords blog. Oxford American Dictionaries. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Flood, Alison (27 April 2013). "Gif is America's word of the year? Now that's what I call an omnishambles". Books blog. The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Olsen, Steve. "The GIF Pronunciation Page". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ a b c "Gif's inventor says ignore dictionaries and say 'Jif'". BBC News. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Buck, Stephanie (21 October 2014). "70 percent of people worldwide pronounce GIF with a hard g". Mashable. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ van der Meulen, Marten (22 May 2019). "Obama, SCUBA or gift?: Authority and argumentation in online discussion on the pronunciation of GIF". English Today. 36 (1): 45–50. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "GIF". The American Heritage Abbreviations Dictionary, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ "GIF". The Cambridge Dictionary of American English. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Gif - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "GIF". Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "gif noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "GIF | Definition of GIF by Oxford Dictionary". Lexico. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus, ed. (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199571123. OCLC 729551189. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 711.

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd ed.). 2012. (part of the Macintosh built-in dictionaries).

- ^ O'Leary, Amy (21 May 2013). "An Honor for the Creator of the GIF". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b Rothberg, Daniel (4 December 2013). "'Jeopardy' wades into 'GIF' pronunciation battle". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ O'Leary, Amy (23 May 2013). "Battle Over 'GIF' Pronunciation Erupts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Valinsky, Jordan (February 25, 2020). "Jif settles the great debate with a GIF peanut butter jar". CNN. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Marur, D.R.; Bhaskar, V. (March 2012). "2012 International Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS)". Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS). International Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS). Karunya University; Coimbatore, India: IEEE. pp. 297–301. doi:10.1109/ICDCSyst.2012.6188724. ISBN 9781457715457. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ S. Chin; D. Iverson; O. Campesato; P. Trani (2011). Pro Android Flash (PDF). New York: Apress. p. 350. ISBN 9781430232315. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bakhshi, Saeideh; Shamma, David A.; Kennedy, Lyndon; Song, Yale; de Juan, Paloma; Kaye, Joseph "Jofish" (7 May 2016). "Fast, Cheap, and Good: Why Animated GIFs Engage Us". Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. pp. 575–586. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858532. ISBN 9781450333627. S2CID 7417853. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ Highfield, Tim; Leaver, Tama (2016). "Instagrammatics and digital methods: studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji". Communication Research and Practice. 2 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/22041451.2016.1155332. hdl:20.500.11937/36939. S2CID 148538216. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Andreas Kleinert (2007). "GIF 24 Bit (truecolor) extensions". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b Philip Howard. "True-Color GIF Example". Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Nullsleep - Jeremiah Johnson - Animated GIF Minimum Frame Delay Browser Compatibility Study". Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "They're different! How to match the animation rate of gif files accross [sic] browsers". Developer's Blog. 14 February 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Royal Frazier. "All About GIF89a". Archived from the original on 18 April 1999. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Scott Walter (1996). Web Scripting Secret Weapons. Que Publishing. ISBN 0-7897-0947-3.

- ^ "XMP Specification Part 3: Storage in Files" (PDF). Adobe. 2016. pp. 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Greg Roelofs. "History of the Portable Network Graphics (PNG) Format". Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Stuart Caie. "Sad day... GIF patent dead at 20". Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ US 4558302, Welch, Terry A., published 1985-12-10, assigned to Sperry Corp.

- ^ JP patent S5719857A, Kanatsu, Jiyun, "Data compression storage device", published 1982-02-02, assigned to Nippon Electric Corp.

- ^ JP patent S57101937A, Kanatsu, Jiyun, "Data storage device", published 1986-20-24, assigned to Nippon Electric Corp.

- ^ DE patent 3118676, Eckhart, Heinz Karl, "Verfahren zur Kompression redundanter Folgen serieller Datenelemente [Method for compressing redundant sequences of serial data elements]", published 1982-12-02

- ^ U.S. patent 4,558,302

- ^ a b "The GIF Controversy: A Software Developer's Perspective". 27 January 1995. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Unisys Clarifies Policy Regarding Patent Use in On-Line Service Offerings". Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. – archived by League for Programming Freedom

- ^ "Libungif". Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Cargill, Tom (1 October 2001). "Replacing a Dictionary with a Square Root". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "LZW Software and Patent Information". Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2007. – clarification of 2 September 1999

- ^ Unisys Not Suing (most) Webmasters for Using GIFs Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Slashdot investigation into the controversy

- ^ "Burn All GIFs Day". Archived from the original on 13 October 1999.

- ^ Burn All GIFs Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine – A project of the League for Programming Freedom (latest version)

- ^ a b c "License Information on GIF and Other LZW-based Technologies". Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2005.

- ^ "Why There Are No GIF Files on GNU Web Pages". Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "PNG versus GIF Compression". 31 March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "AlphaImageLoader Filter". Microsoft. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "What's New in Internet Explorer 7". MSDN. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ "PNG Image File Format". Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Can I use... Support tables for HTML5, CSS3, etc". caniuse.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "VOTE FAILED: APNG 20070405a". SourceForge mailing list. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Discussion for a simple "animated" PNG format". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "APNG Specification". Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Mozilla Labs » Blog Archive » Better animations in Firefox 3". 13 August 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "195280 – Removal of MNG/JNG support". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "18574 – (mng) restore support for MNG animation format and JNG image format". Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Chromium Blog: Chrome 32 Beta: Animated WebP images and faster Chrome for Android touch input". Blog.chromium.org. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Calou, Juan. "SVG Animation - A Guide". Toptal. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Introducing GIFV - Imgur Blog". imgur.com. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Thomson, Gavin; Shah, Athar (2017). "Introducing HEIF and HEVC" (PDF). Apple Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "HEIF Comparison - High Efficiency Image File Format". Nokia Technologies. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "#3271 (Allow using additional pixel formats with libvpx-vp9) – FFmpeg". trac.ffmpeg.org. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin. "Meet the technology that could make GIFs obsolete". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "WebM support on 4chan". 4chan Blog. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Introducing GIFV". Imgur. 9 August 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Allan, Patrick (9 October 2014). "Imgur Revamps GIFs for Faster Speeds and Higher Quality with GIFV". Lifehacker. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "GIF Revolution". Official Telegram Blog. 4 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

External links

[edit]- The GIFLIB project

- spec-gif89a.txt GIF 89a specification on w3.org

- GIF 89a specification reformatted into HTML

- LZW and GIF explained

- Animated GIFs: a six-minute documentary produced by Off Book (web series)