Dragoman of the Porte

The Dragoman of the Sublime Porte (Ottoman Turkish: tercümân-ı bâb-ı âlî; Greek: διερμηνέας της Υψηλής Πύλης, romanized: diermineas tis Ypsilis Pylis), Dragoman of the Imperial Council (tercümân-ı dîvân-ı hümâyûn), or simply Grand Dragoman (μέγας διερμηνέας, megas diermineas) or Chief Dragoman (tercümân başı), was the senior interpreter of the Ottoman government—frequently referred to as the "Sublime Porte"—and de facto deputy foreign minister. From the position's inception in 1661 until the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the office was occupied by Phanariotes, and was one of the main pillars of Phanariote power in the Ottoman Empire.

History

[edit]In the Ottoman Empire, the existence of official interpreters or dragomans[a] is attested from the early 16th century. They were part of the staff of the reis ül-küttab ('head secretary'), who was responsible for foreign affairs within the Imperial Council. As few Ottoman Turks ever learned European languages, from early times the majority of these men were of Christian origin—in the main Austrians, Hungarians, Poles, and Greeks.[1][2] A dragoman may have already existed under Mehmed II (r. 1444–1446, 1451–1481), when Lütfi Bey was sent to conclude a peace treaty with the Republic of Venice.[3] The first known holder of such a post was a certain Ali Bey, who conveyed a treaty to Venice in 1502. His successor was Yunus Bey, a Greek convert to Islam, who was in turn followed by Ahmad, a German convert initially called Heinz Tulman. By the middle of the 16th century there were apparently several dragomans in the service of the Ottoman government—all of whom were Christians—one of whom apparently served as chief dragoman (baş tercümân).[2]

In 1661, the Grand Vizier Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha appointed the Greek Panagiotis Nikousios as Chief Dragoman to the Imperial Council. He was in turn succeeded in 1673 by another Greek, Alexander Mavrocordatos.[1][4] These men began a tradition where almost all subsequent Grand Dragomans of the Porte were members of a small circle of Phanariote families.[1][4] The Phanariotes, taking their name from the district of Constantinople where the Patriarchate of Constantinople settled in 1599, were an elite group of Greek or Hellenized[b] magnate families that made enormous fortunes through trade and tax-farming. Their wealth, and the close contacts they had with the Ottoman sultan and his court as purveyors, advisors, and middlemen, they acquired enormous political influence, especially over the Patriarchate and the Eastern Orthodox communities of the empire more generally.[6] During the 17th century, many Phanariotes gained political experience as representatives (kapı kehaya) of the princes (voivodes or hospodars) of the tributary Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia at the Sultan's court, where, in the words of C. G. Patrinelis, "their task was to sustain their masters’ always precarious position by bribing Ottoman officials in key positions and, above all, to pre-empt and disrupt, by hook or by crook, the machinations of the rivals who coveted the princes’ enviable posts".[7] Others had also served in the staffs of the European embassies in Constantinople.[8] Nikousios, for instance, had previously (and for a time concurrently) served as translator for the Austrian embassy.[9]

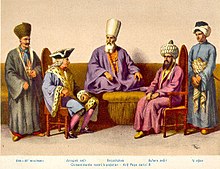

All dragomans had to be proficient in the elsine-i selase, the 'three languages'—Arabic, Persian, and Turkish—that were commonly used in the empire's administration, as well as a number of foreign languages (usually French and Italian).[10] Due to their education in Italy, some spoke Latin as well.[11] In practice, however, the responsibilities of Dragoman of the Porte went beyond that of an interpreter; as the historian Douglas Dakin writes, "[the Dragoman] had become virtually the foreign secretary for European affairs".[12] The salary of the Dragoman of the Porte amounted to 47,000 kuruş[c] annually.[14] The post was the highest public office available to non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire,[15] and bound with privileges otherwise denied to the Christian subjects of the Porte, such as permission to grow a beard; dress in the same kaftans as the Ottoman officials, and use ermine fur; or the permission to ride a horse. Other privileges also followed, such as tax exemption for themselves, their sons, and 20 members of their retinue (twelve servants and eight apprentices); exemption from all customs fees for items destined for their personal use; and immunity from all courts except from that of the Grand Vizier.[d] All these privileges made the position highly coveted, and as the office was often handed down within the same family, it became a chief object of the Phanariotes' aspirations and rivalries.[17][18]

The success of the post led to the creation of a similar office, that of Dragoman of the Fleet, in 1701.[14][19] In practice, the latter often served as a stepping-stone to the office of Grand Dragoman.[14][17] There were also junior dragomans for specific jurisdictions, for example for the Ottoman army, or for the Morea Eyalet, but these positions were never formalized in the same manner.[10][20] From 1711, many former Grand Dragomans or Dragomans of the Fleet were appointed to the positions of princes of the Danubian Principalities. These four offices formed the foundation of Phanariote prominence in the Ottoman Empire.[21][22] The knowledge of foreign languages also made the Phanariote dragomans crucial intermediaries for the transmission of European concepts and technologies to the Ottoman Empire during the latter's attempts at modernization. Thus the Grand Dragoman Constantine Ypsilantis translated French military manuals for the reformed Nizam-i Djedid Army,[23] while Iakovos Argyropoulos translated into the Ottoman Turkish language from French the first modern Ottoman geographical work, as well as a biographical history of Catherine the Great.[24]

The Phanariotes maintained this privileged position until the outbreak of the Greek Revolution in 1821: the then Dragoman of the Porte, Constantine Mourouzis was beheaded, and his successor, Stavraki Aristarchi, was dismissed and exiled in 1822.[1][25] The position of Grand Dragoman was then replaced by a guild-like Translation Bureau, staffed initially by converts like Yahya Efendi and Ishak Efendi, but quickly exclusively by Muslim Turks fluent in foreign languages.[1][26][27]

List of Dragomans of the Porte

[edit]| Name | Portrait | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panagiotis Nikousios | – | 1661–1673[28][29] | A native of Chios and alumnus of the University of Padua, he became a confidante of Grand Vizier Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha as the latter's physician, before being appointed as Dragoman of the Porte.[19][30] He played a leading role in the negotiations that ended the long Siege of Candia in 1669.[31] |

| Alexander Mavrocordatos |

|

1673–1709[28][32] | Scion of the wealthy Phanariote Mavrokordatos family, alumnus of the Pontifical Greek College of Saint Athanasius, the University of Padua and the University of Bologna, he also became physician to Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha before succeeding Nikousios.[19][33][34] Briefly imprisoned and relieved of his duties after the Siege of Vienna,[35] His most notable achievement was as Ottoman representative at the Treaty of Karlowitz that ended the Great Turkish War, for which he received the title of mahrem-i esrar ('keeper of secrets') of the Sultan, and of Imperial Count.[36][37] |

| Nicholas Mavrocordatos |

|

1689–1709[28][38] | Son of Alexander, he deputized for his father during the latter' final years, when illness incapacitated him.[38] After his tenure as Dragoman of the Porte he became the first Phanariote Prince of Moldavia (1711–1715) and Prince of Wallachia (1715–1716, 1719–1730).[39] During the Austro-Turkish War he remained loyal to the Ottomans, and was captured by the Austrians and held until 1719, when he was released and resumed his post as ruler of Wallachia until his death in 1730.[40] |

| John Mavrocordatos | – | 1709–1717[28][41] | Son of Alexander, he succeeded his brother Nicholas as Grand Dragoman. He was also appointed as Caimacam of Moldavia (1711), and then as Prince of Wallachia (1716–1719) during his brother's captivity, until his own death from illness at Bucharest.[28][42] |

| Gregory (II) Ghica |

|

1717–1727[28][43] | The paternal grandson of Gregory I Chica, Prince of Wallachia, and maternal grandson of Alexander Mavrocordatos, Gregory began his career as dragoman of the Austrian Embassy, before succeeding his uncle John Mavrocordatos.[44] Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1726–1733, 1735–1739, 1739–1741, 1747–1748) and of Wallachia (1733–1735, 1748–1752).[28] |

| Alexander Ghica | – | 1727–1740[45][46] | Brother of Gregory, he succeeded him when the latter became Prince of Moldavia.[46] Participated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739, and was executed due to the enmity of the Grand Vizier in 1741.[47] |

| John Theodore Callimachi |

|

1741–1750[45][48] | 1st term. The scion of a native Moldavian family, he was related to the Ghica clan from his mother, and gained advancement as an expert on Polish affairs with the support of Gregory Ghica. His first term was ended when he was sent to exile in Tenedos due to court rivalries with the Ghica.[49][50] |

| Matthew Ghica |

|

1751–1752[28][51] | Second son of Gregory, he purchased the office at a very young age without experience. For this reason his father gave him the dragoman of the Swedish Embassy, Loukakis, as an aide.[51] Subsequently he succeeded his father as Prince of Wallachia (1752–1753) and then became Prince of Moldavia (1753–1756)[28][52] |

| John Theodore Callimachi |

|

1752–1758[45][53] | 2nd term. Recalled from exile after Matthew Ghica became Prince of Wallachia. Subsequently he himself became Prince of Moldavia (1758–1761).[45][53] |

| Gregory (III) Ghica |

|

1758–1764[45] | Son of Alexander and nephew of Gregory II.[54] Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1764–1767, 1774–1782) and of Wallachia (1768–1769).[45] |

| George Caradja | – | 1764–1765[45][55] | Son of Skarlatos, multilingual and a physician, he was named Dragoman of the Porte upon Gregory Ghica's promotion to Prince of Moldavia. He died of the plague after a year in office.[55] |

| Skarlatos Caradja | – | 1765–1768[45][56] | 1st term. Father of George, an experienced diplomat and polyglot and a celebrated physician, he served as his son's successor until the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, when is advanced age precluded him from following the Grand Vizier on campaign.[56] |

| Nicholas Soutzos | – | 1768–1769[45][57] | A specialist in Asian languages, he was appointed to accompany the Grand Vizier Nişancı Mehmed Emin Pasha on campaign, but was arrested for treason in 1769 and executed.[58] |

| Mihai Racoviță | – | 1769–1770 | Son of the namesake Prince of Moldavia and Wallachia, he served as Dragoman of the Porte for Grand Vizier Moldovancı Ali Pasha, but he fell ill and died of the plague while on campaign.[59] |

| Skarlatos Caradja | – | 1770–1774[45][59] | 2nd term. Recalled to the post after the sudden death of Racoviță, he was sent to accompany the Grand Vizier on campaign and remained in office for the duration of the Russo-Turkish War.[60] |

| Alexander Ypsilantis |

|

1774[45] | Son of the distinguished diplomat John Ypsilantis and married to Aikaterini Mourouzi, Alexander was well versed in several languages and became Dragoman of the Porte at a relatively young age. His tenure lasted little over a month, as he was appointed Prince of Wallachia (1774–1782, 1796–1797) and then of Moldavia (1786–1788). His tenure in Moldavia was troubled by the wars with Russia and with Austria. He was executed in 1807 due to his son Constantine Ypsilantis's defection to the Russians.[45][61] |

| Constantine Mourouzis |

|

1774–1777[45][62] | Great-grandson of Nikousios.[63] Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1764–1765),[45] and subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1777–1782).[45][62] |

| Nicholas Caradja | – | 1777–1782[45][64] | Son of Constantine Caradja. He was taken prisoner of war by the Russians during the war of 1768–1774. After his tenure he was appointed Prince of Wallachia (1782–1783), until the machinations of his rival, Michael Drakos Soutzos, led to his replacement by the latter.[45][64] |

| Michael Drakos Soutzos |

|

1782–1783[45][65] | Son of Constantine Soutzos. His tenure was brief as he managed to bribe himself to an appointment as Prince of Wallachia (1783–1786, again in 1791–1793, 1801–1802) and of Moldavia (1793–1795)[45][66] |

| Alexander Mavrocordatos Firaris |

|

1782–1783[45][67] | Son of John II Mavrocordatos, Prince of Moldavia, he was intelligent and well educated.[67] He served as Dragoman of the Porte until he too was appointed as Prince of Moldavia (1785–1786).[45] During the Austro-Russian war against the Ottomans he sided with the former, forcing him to flee into exile, first to Moravia and then to Russia, whence his nickname "Firaris" (Φιραρής, lit. 'fugitive').[67] |

| Alexander Callimachi |

|

1785–1788[45][68] | 1st term.[45] A younger son of John Theodore,[50] he was a well-educated, gentle and pious man. He was replaced as Dragoman after the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792, ostensibly as he was unable to follow the army in the field,[68] but in reality due to pressure from the anti-Russian and pro-French faction at court.[50] |

| Constantine Ralettos | – | 1788[68] | Scion of a wealthy family of Italian origin and brother-in-law of Alexander Ypsilantis, he followed Koca Yusuf Pasha into campaign, but was arrested after a couple of months and exiled to Gallipoli on suspicion of collusion with Ypsilantis against the Porte.[69] |

| Manuel Caradja | – | 1788–1790[45][70] | Holding the rank of Grand Postelnic, he accompanied Ralettos as an aide and succeeded him upon the latter's arrest. He remained in office until replaced by his rival, Alexander Mourouzis.[71] |

| Alexander Mourouzis |

|

1790–1792[45][72] | Son of Constantine. During his tenure he helped mediate the treaties of Sistova (1791) and Jassy (1792), ending the Austro-Turkish and Russo-Turkish wars.[72] As a reward he was made Prince of Moldavia (1792), leaving the office of Grand Dragoman to his younger brother, George.[73] Subsequently several times Prince of Moldavia (1802–1806, 1806–1807) and of Wallachia (1793–1796, 1799–1801).[45] |

| George Mourouzis | – | 1792–1794[45][74] | 1st term.[45] Son of Constantine and brother of Alexander, whom he represented at the Grand Vizier's camp while he was absent in negotiations of the peace treaties. Initially he refused the office, recommending his younger brother Demetrios instead, but the latter also refused. His tenure was cut short by palace intrigues that resulted in the recall of Alexander Callimachi.[75] |

| Alexander Callimachi |

|

1794–1795[45][76] | 2nd term until his appointment as Prince of Moldavia (1795–1799).[45][76] Died at Bolu in 1821, in exile after the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence.[50] |

| George Mourouzis | – | 1795–1796[45][77] | 2nd term.[45] His tenure was ended in August 1796 due to the enmity of the Kapudan Pasha. He was appointed to a post in Cyprus instead, but died there, possibly poisoned.[77] |

| Constantine Ypsilantis |

|

1796–1799[45][78] | Son of Alexander. He was involved in an abortive anti-Ottoman conspiracies in 1782,[79][80] which led him to flee to Germany with his brother Demetrios, where he was educated.[79] He returned to Constantinople and became Grand Dragoman in 1796, in conjunction with his father's appointment as Prince of Moldavia.[81] He played a role in the anti-French turn of the Ottoman Empire, culminating in its joining the Second Coalition, and sponsored the creation of the Septinsular Republic.[82] Subsequently he was appointed Prince of Moldavia (1799–1801) and of Wallachia (1802–1806).[45] |

| Alexandros Soutzos |

|

1799–1801[45] | Son of Nicholas. Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1797–1799).[45] He played a major role in the creation of the Septinsular Republic.[83] Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1801–1802) and of Wallachia (1819–1821).[45] |

| Scarlat Callimachi |

|

1801–1806[45] | Son of Alexander, he received an excellent education and was active in the office of the Grand Dragoman from an early age. Due to services rendered to the French mission under General Sebastiani, he received promotion to the post of Prince of Moldavia in 1806.[50] Subsequently again Prince of Moldavia (1812–1819).[45] Intended to replace Michael Soutzos in Wallachia in 1821, after the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence he was exiled to Bolu and executed.[84] |

| Alexandros M. Soutzos | – | 1802–1807[85][83] | Son of Michael Drakos Soutzos.[86] He was decapitated in October 1807 due to British pressure, accused of having leaked confidential agreements between the Porte, Russia, and Britain to Sebastiani.[87] |

| Alexander Hangerli |

|

1806–1807[45] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1807).[45] After the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, he fled to Russia, where he compiled a celebrated French-Arabic-Persian-Turkish dic- |

| John Caradja |

|

1807–1808[45] | Son of George Caradja.[90] 1st term in succession to Alexandros M. Soutzos, deposed after a short period of time.[45][91] |

| John N. Caradja | – | 1808[45][91] | Son of Nicholas and previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1799–1800[45] or 1802–1806[92]). He died of pleurisy after only two months in office.[90][93] |

| Demetrios Mourouzis | – | 1808–1812[85] | He spent much of his time on campaign alongside the Grand Vizier, due to the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–1812, leaving his brother Panagiotis as his deputy in Constantinople. He negotiated the Treaty of Bucharest that concluded the war, but after protests by Napoleon he was recalled and executed in October 1812.[94] |

| Panagiotis Mourouzis | – | 1809–1812[45] | Younger brother of Demetrios. Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1803–1806),[45] he replaced his brother while the latter was absent from the capital. He was also executed in 1812.[94] |

| John Caradja |

|

1812[45][95] | 2nd term, also cut short on his promotion to Prince of Wallachia (1812–1819).[45][96] |

| Iakovos Argyropoulos | – | 1812–1815[97][98] | Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1809),[85] and envoy to the Prussian court in Berlin.[99][100] He remained in office for three years, until he was ousted following the intrigues of Michael Soutzos.[97] |

| Michael Soutzos |

|

1815–1818[101][102] | Grandson of Michael Drakos Soutzos, he became secretary of John Caradja in 1812, and married the latter's daughter, Roxani.[103] During his tenure as Grand Dragoman, he was the sole Christian member of the eight-member privy council of Sultan Mahmud II.[104] He subsequently was ppointed Prince of Moldavia (1819–1821),[85] serving in the post until the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, when he surrendered his authority to Alexander Ypsilantis.[105][106] In later life he served as ambassador of the Kingdom of Greece in Paris, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, and Copenhagen.[107] |

| John Callimachi | – | 1818–1821[45][108] | Younger brother of Scarlat.[84] Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1800–1803),[45] he was exiled at Kayseri soon after news of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence reached Constantinople, and executed there after the Fall of Tripolitsa.[84][108] |

| Constantine Mourouzis | – | 1821[85] | Son of Alexander, he was appointed to the office mere weeks before the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence. In April he was arrested and executed in the presence of the Sultan, followed soon after by his brother, Demetrios, who was Dragoman of the Fleet.[109][110] |

| Stavraki Aristarchi | – | 1821–1822[85] | Originally a banker for Scarlat Callimachi and appointed postelnic by the latter, he was selected as Grand Dragoman because he did not belong to the traditional Phanariote families. The convert Yahya Efendi was also installed as his deputy, to be trained in his profession and eventually replace him. Aristarchi's chief duty during his tenure was supervising the execution of Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople. He was exiled to Bolu in June 1822, where he was later executed.[111][112] |

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The term is derived from the Italian rendering drog[o]man of Arabic tardjumān, Ottoman tercümân.[1]

- ^ For example, the Callimachi family was originally Romanian, the Aristarchi were Armenians from the Black Sea coast, while the Ghica were from Albania.[5][4]

- ^ The kuruş was the highest-denomination silver coinage, worth about five times the daily wage of an unskilled labourer in the capital, Constantinople, during the early 18th century.[13]

- ^ In Ottoman law and practice, the Grand Vizier was not only the head of the Imperial Council and chief military commander, but also the plenipotentiary or "absolute deputy" of the Sultan.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Bosworth 2000, p. 237.

- ^ a b Kramers 1934, p. 725.

- ^ Paker 2009, p. 550.

- ^ a b c Patrinelis 2001, p. 181.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 16, 28.

- ^ Patrinelis 2001, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Patrinelis 2001, p. 179.

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 237.

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 238.

- ^ a b Philliou 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 30, 69.

- ^ Dakin 1973, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Pamuk 2000, pp. 160–161, esp. note 10.

- ^ a b c Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 243.

- ^ Strauss 1995, p. 190.

- ^ İnalcık 2000, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b Paker 2009, p. 551.

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 242.

- ^ a b c Strauss 1995, p. 191.

- ^ Paker 2009, pp. 550–551.

- ^ Patrinelis 2001, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 11, 183–185.

- ^ Strauss 1995, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Strauss 1995, pp. 196–203.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 72, 92.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 92ff..

- ^ Paker 2009, p. 552.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Philliou 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 29.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 43–54.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 60.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 65–69.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Philliou 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 73–78.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 94.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 11, 25, 183.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 98–100.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 115.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 99–100, 115–116.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 117.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Philliou 2011, p. 184.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 122.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 124.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d e Koromilas 1933a, p. 572.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 125.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 127.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 130.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 131.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 132.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 133.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 134.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 137–141.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 142.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 56.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 143.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 144.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c Stamatiadis 1865, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Stamatiadis 1865, p. 146.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 147.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 148.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 149.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 150.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 151.

- ^ a b Dakin 1973, pp. 28, 35.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 152.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 156.

- ^ a b c Koromilas 1933a, p. 573.

- ^ a b c d e f Philliou 2011, p. 185.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 157.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Philliou 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Vellianitis 1934, p. 466.

- ^ a b Koromilas 1933b, p. 810.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 158.

- ^ Koromilas 1933a, p. 810.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 159.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 161.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b Strauss 1995, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Philliou 2011, p. 85.

- ^ Strauss 1995, p. 196.

- ^ Philliou 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 86, 185.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 168.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 169.

- ^ Philliou 2011, p. 86.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, p. 171.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Stamatiadis 1865, p. 175.

- ^ Vellianitis 1931, p. 425.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 181–184.

- ^ Stamatiadis 1865, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Philliou 2011, pp. 72–73, 85, 91–92.

Sources

[edit]- Bosworth, C. E. (2000). "Tard̲j̲umān". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Dakin, Douglas (1973). The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821–1833. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02342-0.

- İnalcık, Halil (2000) [1973]. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-8421-2442-0.

- Koromilas, G. D. (1933a). "Καλλιμάχης". Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα, Τόμος Δέκατος Τρίτος. Ἴλιτζα – Καστέλλιον (in Greek). Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd. pp. 572–573.

- Koromilas, G. D. (1933b). "Καρατζᾶς". Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα, Τόμος Δέκατος Τρίτος. Ἴλιτζα – Καστέλλιον (in Greek). Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd. p. 810.

- Kramers, J. H. (1934). "Tard̲j̲umān". In Houtsma, M. Th.; Wensinck, A. J.; Gibb, H. A. R.; Heffening, W.; Lévi-Provençal, E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples, Volume IV: S–Z. Leiden and London: E. J. Brill. pp. 725–726.

- Paker, Saliha (2009). "Turkish tradition". In Baker, Mona; Saldanha, Gabriela (eds.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies (Second ed.). Routledge. pp. 550–559. ISBN 978-0-415-36930-5.

- Pamuk, Şevket (2000). A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44197-8.

- Patrinelis, C. G. (2001). "The Phanariots Before 1821". Balkan Studies. 42 (2): 177–198. ISSN 2241-1674.

- Philliou, Christine M. (2011). Biography of an Empire: Governing Ottomans in an Age of Revolution. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26633-9.

- Stamatiadis, Epameinondas (1865). Βιογραφίαι τῶν Ἑλλήνων Μεγάλων Διερμηνέων τοῡ Ὀθωμανικοῡ Κράτους [Biographies of the Greek Great Dragomans of the Ottoman State] (in Greek). Athens: K. Tefarikis.

- Strauss, Johann (1995). "The Millets and the Ottoman Language: The Contribution of Ottoman Greeks to Ottoman Letters (19th–20th Centuries)". Die Welt des Islams. 35 (2): 189–249. doi:10.1163/1570060952597860.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. (1973). Ιστορία του νέου ελληνισμού, Τόμος Δ′: Τουρκοκρατία 1669–1812 – Η οικονομική άνοδος και ο φωτισμός του γένους (Έκδοση Β′) [History of modern Hellenism, Volume IV: Turkish rule 1669–1812 – Economic upturn and enlightenment of the nation (2nd Edition)] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Emm. Sfakianakis & Sons.

- Vellianitis, Th. (1931). "Μουρούζης". Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα, Τόμος Δέκατος Ἕβδομος. Μεσοποταμία – Μωψ (in Greek). Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd. pp. 424–426.

- Vellianitis, Th. (1934). "Χαντζερῆς, Ἀλέξανδρος". Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα, Τόμος Δέκατος Τέταρτος. Φιλισταῖοι – Ὠώδης (in Greek). Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd. p. 466.