Gottfried Böhm

Gottfried Böhm | |

|---|---|

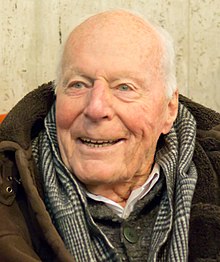

Gottfried Böhm in 2015 | |

| Born | 23 January 1920 |

| Died | 9 June 2021 (aged 101) |

| Alma mater | Technische Hochschule, Munich |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Pritzker Prize |

| Buildings | Maria, Königin des Friedens in Neviges Bensberg City Hall |

Gottfried Böhm (pronounced [ˈɡɔtfʁiːt ˈbøːm]; 23 January 1920 – 9 June 2021) was a German architect and sculptor. His reputation is based on creating highly sculptural buildings made of concrete, steel, and glass. Böhm's first independent building was the Cologne chapel "Madonna in the Rubble" (now integrated into Peter Zumthor's design of the Kolumba museum renovation).[1] The chapel was completed in 1949 where a medieval church once stood before it was destroyed during World War II.[1] Böhm's most influential and recognized building is the Maria, Königin des Friedens pilgrimage church in Neviges.

In 1986, he became the first German architect to be awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize.[2][3][4] Among the most recently completed construction projects involving Böhm are the Hans Otto Theater in Potsdam (2006) and the Cologne Central Mosque, completed in 2018.

In honor of Gottfried Böhm, the City of Cologne has been awarding the Gottfried Böhm Scholarship for postgraduate architects together with the Technische Hochschule Köln and the Verein der Freunde & Förderer der Technischen Hochschule Köln e.V. since 2023.[5]

Early life

[edit]Böhm was born in Offenbach am Main near Frankfurt on 23 January 1920.[6][7] He was the youngest of three children of Maria and Dominikus Böhm. His father was renowned for his numerous avant-garde churches throughout Germany, many in Expressionist style.[4] His grandfather was also an architect. Böhm was conscripted into the Wehrmacht at the outset of World War II. He served until he was injured in 1942 during Operation Barbarossa and consequently returned to Germany.[6] After graduating from the Technische Hochschule, Munich, in 1946,[3] he studied sculpture at a nearby fine-arts academy. Gottfried later integrated his clay model making skills acquired during this time at the academy into his design process.[8]

Career

[edit]After graduating in 1947, Gottfried worked for his father until the latter's death in 1955, and later took over his firm. During this period, he also worked with the "Society for the Reconstruction of Cologne" under Rudolf Schwarz.[1] In 1951, he traveled to New York City and worked for six months in the architectural firm of Cajetan Baumann. While traveling in the United States he met two of his greatest inspirations, German architects Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius.[3]

In the following decades, Böhm constructed many buildings around Germany, including museums, civic centers, office buildings, homes, apartment buildings and churches. He is considered to have been both an expressionist and post-Bauhaus architect, but he preferred to define himself as an architect who created "connections" between the past and the future, between the world of ideas and the physical world, between a building and its urban surroundings. In this vein, Böhm always envisioned the color, form, and materials of a building in relationship with its setting. His earlier projects were done mostly in molded concrete, but more recently he employed more steel and glass in his buildings due to the technical advancements in both materials. His concern for urban planning is evident in many of his projects, harping back to his emphasis on "connections".[3] In addition to Germany, Böhm designed buildings in Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Turin, Italy.[9]

A 2014 documentary titled "Concrete Love – The Böhm Family" explores Gottfried's relationship with his sons and his wife. [10]

Personal life

[edit]Böhm was married to Elizabeth Haggenmüller, also an architect, until her death in 2012.[4] He met her in 1948 while studying in Munich. She assisted him in several of his projects, mainly through interior design.[11] Together, they had four sons: Stephan, Peter, Paul and Markus. The first three also became architects, while Markus worked as a painter.[6] Böhm turned 100 in January 2020.[12]

Böhm died on the night of 9 June 2021 at his home in Cologne,[6][13] aged 101.[14][4][3] The cause of death was not disclosed.[13]

Gottfried Böhm Scholarship

[edit]On the occasion of the 100th birthday of Cologne architect Gottfried Böhm, Cologne Mayor Henriette Reker proposed a scholarship in 2020 in honor of the internationally renowned architect. In 2023, the scholarship will be held for the first time. Postgraduate architects can apply until August 31, 2023. The scholarship will start in October 2023 and run for one year.

The Gottfried Böhm Scholarship supports architects in the postgraduate phase who are particularly interested in the connection between architecture and urban development.[15] Under the patronage of Cologne's mayor Henriette Reker the one-year residency scholarship takes place in the metropolis of Cologne. The scholarship holder is given the opportunity to work for one year on creative and visionary tasks in architecture and urban development for Cologne and its periphery. For this period he or she will receive free accommodation, a workplace in a creative environment in the heart of the city and a monthly grant totaling 2,500 euros. The scholarship is offered and supervised by the Verein der Freunde und Förderer der Technischen Hochschule Köln e.V. (Association of Friends and Sponsors of the Cologne University of Applied Sciences).

Notable buildings

[edit]

- 1947–50 St. Kolumba, Cologne[6][7]

- 1962–69 Bensberg City Hall[6][7]

- 1962-65 St. Gertrud, Cologne[16]

- 1968–72 Maria, Königin des Friedens pilgrimage church, Neviges[6][7]

- 1968–70 Christi Auferstehung (Church of Resurrection), Cologne[17]

Awards

[edit]- 1968 – Eduard-von-der-Heydt Prize from the city of Wuppertal[18]

- 1971 – Architecture Prize of the Association of German Architects, Düsseldorf[19]

- 1974 – Berlin Art Prize of the Academy of Arts, Berlin[20][18]

- 1975 – Großer BDA Preis (BDA Grand Award) of the Association of German Architects, Bonn[21][18]

- 1977 – Honorary Professor F. Villareal National University, Lima, Peru[18]

- 1982 – Grande Medaille d'Or d'Architecture, L'Académie d'Architecture in Paris, France[21][18]

- 1983 – Honorary Membership / Honorary Member of the American Institute of Architects AIA[18]

- 1985 – Fritz Schumacher Prize, Hamburg[22][18]

- 1985 – Honorary doctorate, Technical University of Munich[23][18]

- 1985/1986 – Price Cret Chair at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States[24]

- 1986 – Pritzker Architecture Prize, Chicago, US[6][7][18]

- 1987 – Gebhard Fugel Prize, Munich[18]

- 1993 – Rheinischer Kulturpreis[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Goldmann, A. J. (10 June 2021). "Gottfried Böhm, Master Architect in Concrete, Dies at 101". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Jury Citation". pritzkerprize.com. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Valencia, Nicolas (10 June 2021). "Pritzker Prize Laureate Gottfried Böhm Passes Away at 101". ArchDaily. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d DER SPIEGEL (10 June 2021). "Kirchen wie Gebirge, Rathäuser wie Burgen: Der Architekt und Betonkünstler Gottfried Böhm ist tot". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Startschuss zum ersten Gottfried-Böhm-Stipendium". Deutsche Bauzeitung. 22 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goldmann, A. J. (10 June 2021). "Gottfried Böhm, Master Architect in Concrete, Dies at 101". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Dege, Stefan (10 June 2021). "Star architect Gottfried Böhm has died aged 101". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Gottfried Böhm". architectuul.com. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Goldmann, A.J. (10 June 2021). "Gottfried Böhm, Master Architect in Concrete, Dies at 101". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldman, A.J. (10 June 2021). "Gottfried Böhm, Master Architect in Concrete, Dies at 101". The New York Times.

- ^ Hiltrud Kier, Bauten und Projekte in: Kristin Feireiss (ed.): Elisabeth Böhm: Stadtstrukturen und Bauten, p. 64 (in German)

- ^ "As Gottfried Böhm Turns 100, an Exhibition Celebrates His Brutalist Church". 4 March 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Gottfried Boehm, architect of concrete churches, dies at 101". Associated Press. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Felten, Uwe (10 June 2021). "Baumeister mit Faible für Beton: Gottfried Böhm im Alter von 101 Jahren gestorben". RP ONLINE. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Gottfried Böhm Scholarship". Verein der Freunde & Förderer der Technischen Hochschule Köln e.V. 12 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ https://www.katholisch-in-koeln.de/ueber-uns/st-gertrud/index.html

- ^ "Moschee, Maritim und Co.: Das sind die bekanntesten Gebäude von Gottfried Böhm in Köln". Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021. (in German)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Böhm". Akademie der Künste, Berlin (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Auf der Suche nach dem Gemeinsamen – BDA". der architekt (in German). 16 April 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Berlin Art Prize – Jubilee Endowment 1848/1948". Berlin: Academy of Arts. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b Muhidine, Eléonore (13 April 2021). "Déconstructiviste Avant L'Heure". Le Moniteur. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021. (in French)

- ^ "Gottfried Bohm". GreatBuildings. ArchitectureWeek. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Ehrendoktoren". Technical University of Munich. Retrieved 10 June 2021. (in German)

- ^ Winship, Frederick M. (17 April 1986). "German Architect wins $100,000 Pritzker Prize". United Press International. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

External links

[edit]- 1920 births

- 2021 deaths

- People from Offenbach am Main

- 20th-century German architects

- Brutalist architects

- German sculptors

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Members of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Pritzker Architecture Prize winners

- Technical University of Munich alumni

- Polytechnic University of Catalonia

- Academic staff of RWTH Aachen University

- German men centenarians

- German Army personnel of World War II