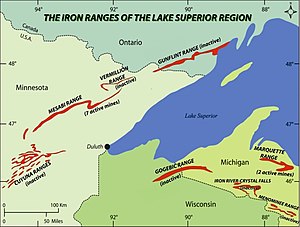

Gogebic Range

The Gogebic Range is an elongated area of iron ore deposits located within a range of hills in northern Michigan and Wisconsin just south of Lake Superior. It extends from Lake Namakagon in Wisconsin eastward to Lake Gogebic in Michigan, or almost 80 miles. Though long, it is only about a half mile wide and forms a crescent concave to the southeast. The Gogebic Range includes the communities of Bessemer and Ironwood in Michigan, plus Mellen and Hurley in Wisconsin.[1]

The name Gogebic is an Anglicized spelling from old style Ojibwe “googii-bi”, which loosely translates to "they dive here", most likely referring to the schools of fish that jump from the surface of Lake Gogebic. "Range" is the term commonly used for such iron ore areas around Lake Superior. In Wisconsin, the Gogebic Range is often called the Penokee Range. The range is named after Lake Gogebic, a large lake near the east end of the range in Gogebic and Ontonagon Counties in Michigan.

Located within the southern of two parallel prominent ridges, the Gogebic range iron formation name is often used interchangeably with the range of hills that encompass it. The hills composing the Gogebic range vary from 100 to 600 feet above the surrounding terrain, and are a prominent landform visible for miles. The Gabbro, or Trap Range comprises a somewhat lower ridge of hills running parallel just to the north of the Gogebic Range. Since the two ranges of hills are made up of dissimilar rock types, the rock formation containing the iron ore deposits is located exclusively within the southern (Gogebic) Range.

The Gogebic Range experienced a speculative iron boom in the mid-1880s, and had recurring booms and busts from 1884 to 1967 as demand shifted.

Iron boom

[edit]

The iron formation rocks forming the Gogebic Range were created by iron-rich sediments laid down within a shallow sea nearly 2 billion years ago. Later, the region was uplifted to such an extent that the resulting mountains rivaled the European Alps of today. Later still, around 1 billion years ago, the region was subjected to extensive volcanism associated with the creation of the Midcontinent Rift System, an event that nearly tore the North American Plate in half before mysteriously ending. The volcanism metamorphosed and modified the rocks to create the iron ores present today. During this geologic activity, the horizontal layers of the iron formation were tipped nearly seventy degrees, such that mines used to extract the ore needed to be extraordinarily deep, extending to over 5,000 feet (1524 m) underground.

The iron comes from the Huronian Ironwood formation. It consists of alternating beds of ferruginous oolitic chert and fine-textured cherty carbonates. Iron minerals make up one third of the formation content, the rest being quartz. The formation was discovered in 1848 by Dr. A. Randall during the Fourth principal meridian survey near Upson, Wisconsin. Ore was first produced in 1883 from the Colby Mine in Michigan.[1]: 19, 23, 90–91, 184

The initial boom in the Gogebic Range came between 1884 and 1886. The discovery of high-grade Bessemer ore on the Gogebic Range and the potential for its exploitation led to a speculative craze the like of which has had no parallel in Michigan or Wisconsin. While it lasted, fortunes were made and lost within a month or even overnight.[2]

On September 16, 1886, the Chicago Tribune reported:

Hundreds of people are arriving daily from all parts of the country and millionaires are being made by the dozens ... The forests have given way to mining camps and towns, and a most bewildering transformation has taken place. In the palmy days of gold mining on the Pacific slope there is no record of anything so wonderful as the Gogebic.

Thousands of immigrants and their families arrived in the region to work in the mines. The immigrants were mostly Finnish, Swedish, Italian, French-Canadian, Austrian, and English ethnicities. Many of the settlers had prior mining experience in their home countries, and were actively recruited by the mining companies in Europe. The influx of settlers created a population boom in the region, and helped establish numerous communities in the Gogebic Range.

Iron ore was shipped via rail from the Gogebic Range to the Lake Superior port in Ashland, Wisconsin where it was loaded onto vessels and shipped to various Great Lakes ports throughout the region for further transport or smelting into Steel.

For decades in the late 19th century and into the 1920s, the Gogebic was one of the nation's chief sources of iron.[1]: 37 Iron from the Gogebic helped to fuel the industrial boom in the Upper Midwest during these years. By 1930 mining was winding down in the area. The mines began closing as the national economy suffered from the Great Depression. The result was widespread economic devastation in the communities of the Gogebic Range.

Some mines continued to operate into the 1960s, but the volume never reached the same levels as in the earlier boom years. A defining event was the last shipment of iron ore in August 1967 to Granite City Steel in Illinois.

Approximately 325 million tons of this ore was mined from around 40 individual mines between 1877 and 1967. Iron mines of the era exploited the "natural" (soft) iron-rich ores in a 15 kilometer-long stretch in the central portion of the range straddling the Michigan-Wisconsin state line. These mines were mainly of the underground shaft type, which were among the deepest iron mines in the country. Due to these characteristics, and the greater associated costs involved with extracting the ore, these mines were unable to compete economically with the larger open pit iron mines in northern Minnesota and elsewhere.

Range today

[edit]

Today the area has largely recovered from the scars left behind by the iron-mining boom days. The Gogebic Range has developed a tourism industry featuring ski resorts and waterfalls. After being clearcut during the unregulated lumbering era during the 19th and early 20th centuries, nearly the entire area has re-grown into extensive second-growth North Woods forests. The region includes vast areas of government-owned public land, including the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, the Ottawa National Forest, and the Iron County and Gogebic County Forests, which are managed for recreation and timber production. Recreational activities include fishing in rivers and lakes, hunting, hiking, and snowmobiling and mountain biking on a network of trails built on old logging roads. A portion of the North Country National Scenic Trail follows the Gogebic range, providing waterfall viewing opportunities and scenic overlooks of the surrounding forests.

With the regrowth of the forests, wildlife returned to the area. Large mammals documented in the region include species such as white-tailed deer, wolves, moose, black bear, and elk, which were recently reintroduced to Wisconsin's Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest.

Gogebic County and neighboring Iron County, across the state line in Wisconsin, are heavily promoted during the ski season as "Big Snow Country". Heavy lake-effect snow from cold northerly winds blowing across the relatively warm waters of nearby Lake Superior result in large annual accumulations of up to 200 inches (5.1 m) of snow in northern Wisconsin and upper Michigan. The steep terrain of the Gogebic Range enhances the lake effect snowfall by providing orographic lift to the air mass, usually providing ample snowfall for winter recreation activities including snowmobiling, Cross-country skiing, downhill skiing, and snowshoeing. Several ski resorts are located along the Gogebic Range including Whitecap Mountain in Iron County and Big Powderhorn Mountain and Snow River Mountain Resorts in Gogebic County. There is also a natural ski hill by Lake Superior at Porcupine Mountains State Park, less than an hour from Ironwood.

The Copper Peak Ski flying hill is located near Ironwood, Michigan. This facility is the only ski flying hill in the western hemisphere, and hosted 10 ski flying events between 1970 and 1994. The 240-foot high tower on top of the Copper Peak hill allowed ski jumpers to fly over 500 feet through the air and provides views of three states and Lake Superior. Although currently not used, plans exist for renovating the facility and the resumption of competitive ski jumping at the hill.

Gogebic County has 22 waterfalls, with ten more across the Montreal River in neighboring Iron County, Wisconsin. Ashland County, Wisconsin also has several waterfalls. Significant waterfalls are located along the Presque Isle and Black rivers within half a mile (0.8 km) of Lake Superior. Other attractions on the east fork of the Montreal River that forms the Michigan–Wisconsin border northwest of Ironwood and Hurley include Superior Falls (which is bordered by 100-foot (30 m) cliffs), Saxon Falls, Interstate Falls, and Peterson Falls. Major waterfalls in Iron County, Wisconsin include Rock Cut, Gile, Kimball, and Spring Camp Falls on the west fork of the Montreal River, Foster, Upson, and Potato River Falls on the Potato River, and Wren Falls on the Tyler Forks River. Major waterfalls in Ashland County, Wisconsin include Copper Falls and Brownstone Falls on the Bad River in Copper Falls State Park.

With metals trading at unprecedented prices during the early 2010s commodity bubble, companies again explored the possibilities of mining in the Gogebic Range to extract remaining, lower-quality ore.[3] The lower-grade Taconite ore of interest was located in the western portion of the Gogebic Range in Wisconsin. Since the closure of the previous mines in the 1960s, the railroads serving the mining region were mostly abandoned and converted to rail trails. Unless lines could be reconstructed (at considerable expense), transportation would have to be by road, which would greatly limit the scope of any proposed mining project. Resumption of mining was generally not considered profitable, and concerns about the health and environmental impact to the region and Lake Superior resulting from the proposed massive miles-long open pit iron mines, associated industrial ore processing facilities, and crushed waste rock tailings disposal created much controversy among area residents and the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians. Major areas of concern related to the proposed mining activities included the presence of extensive pristine wetlands that would be destroyed, the potential of acid mine drainage water pollution from iron sulfide present in the bedrock, the release of hazardous, carcinogenic airborne asbestos-like amphibole fibers from the blasting, crushing, transport, and processing of grunerite rock (containing asbestiform minerals) documented to be present in the bedrock, loss of forest and hunting land, and the industrialization of one of the most scenic undeveloped areas in Wisconsin.

See also

[edit]- Mesabi Range

- Soudan Underground Mine State Park

- Cliffs Shaft Mine Museum

- Cuyuna Range

- Vermilion Range (Minnesota)

- Gunflint Range

- Iron Mountain Central Historic District

- Marquette Iron Range

- Animikie Group

- Banded iron formation

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Aldrich, Henry (1929). The Geology of the Gogebic Iron Range of Wisconsin. State of Wisconsin. p. 5.

- ^ Henry Eduard Legler, Leading Events of Wisconsin History Archived February 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Emily Lambert, "A Mining Rush in the Upper Peninsula," New York Times, May 24, 2012. Accessed May 24, 2012.

https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/main-entry/googii-vai

Further reading

[edit]- Liesch, Matthew. Ironwood, Hurley and the Gogebic

- Cox, Bruce K. Headframes and Mine Shafts of the Gogebic Range, Volume 2, Bessemer-Ramsay-Wakefield: Agogeebic Press, 2000.

- Hunts' Guide to Michigan's Upper Peninsula: Ironwood and the Gogebic Range

- Gogebic Range City Directories, 1888-1947

- Wisconsin Electronic Reader: The Great Boom on the Gogebic

- Gogebic County Government

- Road Trip USA: Ironwood and Environs: The Gogebic Range