History of glass

The history of glass-making dates back to at least 3,600 years ago in Mesopotamia. However, most writers claim that they may have been producing copies of glass objects from Egypt.[1] Other archaeological evidence suggests that the first true glass was made in coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia or Egypt.[2] The earliest known glass objects, of the mid 2,000 BCE, were beads, perhaps initially created as the accidental by-products of metal-working (slags) or during the production of faience, a pre-glass vitreous material made by a process similar to glazing.[n 1] Glass products remained a luxury until the disasters that overtook the late Bronze Age civilizations seemingly brought glass-making to a halt.

Development of glass technology in India may have begun in 1,730 BCE.[3]

From across the former Roman Empire, archaeologists have recovered glass objects that were used in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Anglo-Saxon glass has been found across England during archaeological excavations of both settlement and cemetery sites. Glass in the Anglo-Saxon period was used in the manufacture of a range of objects, including vessels, beads, windows, and was even used in jewellery.

Origins

[edit]

Naturally occurring glass, especially the volcanic glass obsidian, has been used by many Stone Age societies across the globe for the production of sharp cutting tools and, due to its limited source areas, was extensively traded. But in general, archaeological evidence suggests that the first true glass was made in coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt.[2] Because of Egypt's favorable environment for preservation, the majority of well-studied early glass is found there, although some of this is likely to have been imported. The earliest known glass objects, of the mid-third millennium BCE, were beads, perhaps initially created as accidental by-products of metal-working (slags) or during the production of faience, a pre-glass vitreous material made by a process similar to glazing.[n 1]

During the Late Bronze Age in Egypt (e.g., the Ahhotep "Treasure")[4] and Western Asia (e.g., Megiddo),[5] there was a rapid growth in glassmaking technology. Archaeological finds from this period include colored glass ingots, vessels (often colored and shaped in imitation of highly prized hardstone carvings in semi-precious stones) and the ubiquitous beads. The alkali of Syrian and Egyptian glass was soda ash (sodium carbonate), which can be extracted from the ashes of many plants, notably halophile seashore plants like saltwort. The latest vessels were 'core-formed', produced by winding a ductile rope of glass around a shaped core of sand and clay over a metal rod, then fusing it by reheating it several times.[citation needed]

Threads of thin glass of different colors made with admixtures of oxides were subsequently wound around these to create patterns, which could be drawn into festoons by using metal raking tools. The vessel would then be rolled smooth (marvered) on a slab in order to press the decorative threads into its body. Handles and feet were applied separately. The rod was subsequently allowed to cool as the glass slowly annealed and was eventually removed from the center of the vessel, after which the core material was scraped out. Glass shapes for inlays were also often created in moulds. Much of early glass production, however, relied on grinding techniques borrowed from stone working. This meant that the glass was ground and carved in a cold state.[6]

By the 15th century BCE, extensive glass production was occurring in Western Asia, Crete, and Egypt; and the Mycenaean Greek term 𐀓𐀷𐀜𐀺𐀒𐀂, ku-wa-no-wo-ko-i, meaning "workers of lapis lazuli and glass" (written in Linear b syllabic script) is attested.[7][8][9][n 2][n 3] It is thought that the techniques and recipes required for the initial fusing of glass from raw materials were a closely guarded technological secret reserved for the large palace industries of powerful states. Glass workers in other areas therefore relied on imports of preformed glass, often in the form of cast ingots such as those found on the Ulu Burun shipwreck off the coast of modern Turkey.[citation needed]

Glass remained a luxury material, and the disasters that overtook Late Bronze Age civilizations seemed to have brought glass-making to a halt.[citation needed][13] It picked up again in its former sites, Syria and Cyprus, in the 9th century BCE, when the techniques for making colorless glass were discovered.[citation needed]

The first glassmaking "manual" dates back to ca. 650 BCE. Instructions on how to make glass are contained in cuneiform tablets discovered in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.[citation needed]

In Egypt, glass-making did not revive until it was reintroduced in Ptolemaic Alexandria. Core-formed vessels and beads were still widely produced, but other techniques came to the fore with experimentation and technological advancements.[citation needed]

During the Hellenistic period many new techniques of glass production were introduced and glass began to be used to make larger pieces, notably table wares. Techniques developed during this period include 'slumping' viscous (but not fully molten) glass over a mould in order to form a dish and 'millefiori' (meaning 'thousand flowers') technique, where canes of multicolored glass were sliced and the slices arranged together and fused in a mould to create a mosaic-like effect. It was also during this period that colorless or decolored glass began to be prized and methods for achieving this effect were investigated more fully.[14]

According to Pliny the Elder, Phoenician traders were the first to stumble upon glass manufacturing techniques at the site of the Belus River. Georgius Agricola, in De re metallica, reported a traditional serendipitous "discovery" tale of familiar type:

"The tradition is that a merchant ship laden with nitrum being moored at this place, the merchants were preparing their meal on the beach, and not having stones to prop up their pots, they used lumps of nitrum from the ship, which fused and mixed with the sands of the shore, and there flowed streams of a new translucent liquid, and thus was the origin of glass."[15]

This account is more a reflection of Roman experience of glass production, however, as white silica sand from this area was used in the production of glass within the Roman Empire due to its high purity levels. During the 1st century BCE, glass blowing was discovered on the Syro-Judean coast, revolutionizing the industry. The first evidence of the invention of glassblowing was found in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem, in a layer of fill inside a ritual bath that was overlain with the paving stones of the Herodian street.[16] Several other site of producing "Judean Glass" were found in Galilee.[17] Glass vessels were now inexpensive compared to pottery vessels. Growth of the use of glass products occurred throughout the Roman world.[citation needed] Glass became the Roman plastic, and glass containers produced in Alexandria[citation needed] spread throughout the Roman Empire. With the discovery of clear glass (through the introduction of manganese dioxide), by glass blowers in Alexandria circa 100 AD, the Romans began to use glass for architectural purposes. Cast glass windows, albeit with poor optical qualities, began to appear in the most important buildings in Rome and the most luxurious villas of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Over the next 1,000 years, glass making and working continued and spread through southern Europe and beyond.[citation needed]

History by culture

[edit]Iran

[edit]The first Persian glass comes in the form of beads dating to the late Bronze Age (1600 BCE), and was discovered during the explorations of Dinkhah Tepe in Iranian Azerbaijan by Charles Burney. Glass tubes were discovered by French archaeologists at Chogha Zanbil, belonging to the middle Elamite period. Mosaic glass cups have also been found at Teppe Hasanlu and Marlik Tepe in northern Iran, dating to the Iron Age. These cups resemble ones from Mesopotamia, as do cups found in Susa during the late Elamite period.

Glass tubes containing kohl have also been found in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan Province, belonging to the Achaemenid period. During this time, glass vessels were usually plain and colorless. By the Seleucid and late Parthian era, Greek and Roman techniques were prevalent. During the Sasanian period, glass vessels were decorated with local motifs.[18]

India

[edit]Evidence of glass during the chalcolithic has been found in Hastinapur, India.[19] The earliest glass item from the Indus Valley civilization is a brown glass bead found at Harappa, dating to 1700 BCE. This makes it the earliest evidence of glass in South Asia.[3][20] Glass discovered from later sites dating from 600 to 300 BCE displays common colors.[3]

Texts such as the Shatapatha Brahmana and Vinaya Pitaka mention glass, implying they could have been known in India during the early first millennium BCE.[19] Glass objects have also been found at Beed, Sirkap and Sirsukh, all dating to around the 5th century BCE.[21] However, the first unmistakable evidence for widespread glass usage comes from the ruins of Taxila (3rd century BCE), where bangles, beads, small vessels, and tiles were discovered in large quantities.[19] These glassmaking techniques may have been transmitted from cultures in Western Asia.[21]

The site of Kopia, in Uttar Pradesh, is the first site in India to locally manufacture glass, with items dating between the 7th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[22] Early Indian glass of this period was likely made locally, as they differ significantly in chemical composition when compared to Babylonian, Roman and Chinese glass.[21]

By the 1st century AD, glass was being used for ornaments and casing in South Asia.[19] Contact with the Greco-Roman world added newer techniques, and Indians artisans mastered several techniques of glass molding, decorating and coloring by the succeeding centuries.[19] The Satavahana period of India also produced short cylinders of composite glass, including those displaying a lemon yellow matrix covered with green glass.[23]

China

[edit]

In China, glass played a peripheral role in arts and crafts when compared to ceramics and metal work.[24] The earliest glass items in China come from the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), although they are rare in number and limited in archaeological distribution.

Glassmaking developed later in China compared to cultures in Mesopotamia, Egypt and India.[25] Imported glass objects first reached China during the late Spring and Autumn period (early 5th century BCE), in the form of polychrome eye beads.[26] These imports created the impetus for the production of indigenous glass beads.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the use of glass diversified. The introduction of glass casting in this period encouraged the production of moulded objects, such as bi disks and other ritual objects.[25] Chinese glass objects from the Warring States and Han period vary greatly in chemical composition from the imported glass objects. The glasses from this period contain high levels of barium oxide and lead, distinguishing them from the soda–lime–silica glasses of Western Asia and Mesopotamia.[27] At the end of the Han Dynasty (AD 220), the lead-barium glass tradition declined, with glass production only resuming during the 4th and 5th centuries AD.[28] Literary sources also mention the manufacture of glass during the 5th century AD.[29]

Romans

[edit]

Roman glass production developed from Hellenistic technical traditions, initially concentrating on the production of intensely colored, cast glass vessels. Glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire[30] in domestic, funerary[31] and industrial contexts.[32] Glass was used primarily for the production of vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced.

However, during the 1st century CE, the industry underwent rapid technical growth that saw the introduction of glass-blowing and the dominance of colorless or ‘aqua’ glasses. Raw glass was produced in geographically separate locations to the working of glass into finished vessels,[33][34] and, by the end of the 1st century CE, large scale manufacturing, primarily in Alexandria,[35] resulted in the establishment of glass as a commonly available material in the Roman world.

Islamic world

[edit]Islamic glass continued the achievements of pre-Islamic cultures, especially the Sasanian glass of Persia. The Arab poet al-Buhturi (820–897) described the clarity of such glass: "Its color hides the glass as if it is standing in it without a container."[36] In the 8th century, the Persian-Arab chemist Jābir ibn Hayyān (Geber) described 46 recipes for producing colored glass in Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna (The Book of the Hidden Pearl), in addition to 12 recipes inserted by al-Marrakishi in a later edition of the book.[37] By the 11th century, clear glass mirrors were being produced in Islamic Spain.[citation needed]

Africa

[edit]

Evidence suggests that indigenous glass production existed in West Africa well before extensive contact with other glassmaking regions. The most significant and well-documented example is the Ife Empire of Southwestern Nigeria.[38] Archaeological excavations at Igbo Olokun, a site in northern Ife, have yielded a substantial quantity of glass beads, crucibles, and production debris dating from the 11th to 15th centuries CE. chemical analysis revealed a unique chemical signature significantly different from known imported glass types.

The Igbo Olokun glass is characterized by a high-lime, high-alumina (HLHA) composition, reflecting the use of locally sourced raw materials, likely including granitic sands and possibly calcium carbonate from sources such as snail shells. At least two distinct glass types, HLHA and low-lime, high-alumina (LLHA), were produced at Igbo Olokun. Colorants including manganese, iron, cobalt, and copper were intentionally added to produce a range of colors, most notably various shades of dichroic blue and green. Analysis also revealed the presence of glass production waste, including fragments of crucibles bearing vitrified glass residues, confirming the onsite nature of the manufacturing.[39]

Medieval Europe

[edit]

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, independent glass making technologies emerged in Northern Europe, with artisan forest glass produced by several cultures. Byzantine Glass evolved the Roman tradition, in the Eastern Empire. The claw beaker was popular as a relatively easy to make but an impressive vessel that exploited the unique potential of glass.[citation needed]

Glass objects from the 7th and 8th centuries have been found on the island of Torcello near Venice. These form an important link between Roman times and the later importance of that city in the production of the material. Around 1000 AD, an important technical breakthrough was made in Northern Europe when soda glass, produced from white pebbles and burnt vegetation was replaced by glass made from a much more readily available material: potash obtained from wood ashes. From this point on, northern glass differed significantly from that made in the Mediterranean area, where soda remained in common use.[40]

Until the 12th century, stained glass – glass to which metallic or other impurities had been added for coloring – was not widely used, but it rapidly became an important medium for Romanesque art and especially Gothic art. Almost all survivals are in church buildings, but it was also used in grand secular buildings. The 11th century saw the emergence in Germany of new ways of making sheet glass by blowing spheres. The spheres were swung out to form cylinders and then cut while still hot, after which the sheets were flattened. This technique was perfected in 13th century Venice. The crown glass process was used up to the mid-19th century. In this process, the glassblower would spin approximately 9 pounds (4 kg) of molten glass at the end of a rod until it flattened into a disk approximately 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter. The disk would then be cut into panes. Domestic glass vessels in late medieval Northern Europe are known as forest glass.[citation needed]

Anglo-Saxon world

[edit]Anglo-Saxon glass has been found across England during archaeological excavations of both settlement and cemetery sites. Glass in the Anglo-Saxon period was used in the manufacture of a range of objects including vessels, beads, windows and was even used in jewelry.[41] In the 5th century AD with the Roman departure from Britain, there were also considerable changes in the usage of glass.[42] Excavation of Romano-British sites has revealed plentiful amounts of glass but, in contrast, the amount recovered from the 5th century and later Anglo-Saxon sites is minuscule.[42]

The majority of complete vessels and assemblages of beads come from the excavations of early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, but a change in burial rites in the late 7th century affected the recovery of glass, as Christian Anglo-Saxons were buried with fewer grave goods, and glass is rarely found. From the late 7th century onwards, window glass is found more frequently. This is directly related to the introduction of Christianity and the construction of churches and monasteries.[42][43] There are a few Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical[44] literary sources that mention the production and use of glass, although these relate to window glass used in ecclesiastical buildings.[42][43][45] Glass was also used by the Anglo-Saxons in their jewelry, both as enamel or as cut glass insets.[46][47]

Murano

[edit]The center for luxury Italian glassmaking from the 14th century was the island of Murano, which developed many new techniques and became the center of a lucrative export trade in dinnerware, mirrors, and other items. What made Venetian Murano glass significantly different was that the local quartz pebbles were almost pure silica, and were ground into a fine clear sand that was combined with soda ash obtained from the Levant, for which the Venetians held the sole monopoly. The clearest and finest glass is tinted in two ways: firstly, a natural coloring agent is ground and melted with the glass. Many of these coloring agents still exist today; for a list of coloring agents, see below. Black glass was called obsidianus after obsidian stone. A second method is apparently to produce a black glass which, when held to the light, will show the true color that this glass will give to another glass when used as a dye.[48]

The Venetian ability to produce this superior form of glass resulted in a trade advantage over other glass producing lands. Murano’s reputation as a center for glassmaking was born when the Venetian Republic, fearing fire might burn down the city’s mostly wood buildings, ordered glassmakers to move their foundries to Murano in 1291.[citation needed] Murano's glassmakers were soon the island’s most prominent citizens. Glassmakers were not allowed to leave the Republic. Many took a risk and set up glass furnaces in surrounding cities and as far afield as England and the Netherlands.[citation needed]

Bohemia

[edit]

Bohemian glass, or Bohemia crystal, is a decorative glass produced in regions of Bohemia and Silesia, now in the current state of the Czech Republic, since the 13th century.[49] Oldest archaeology excavations of glass-making sites date to around 1250 and are located in the Lusatian Mountains of Northern Bohemia. Most notable sites of glass-making throughout the ages are Skalice (German: Langenau), Kamenický Šenov (German: Steinschönau) and Nový Bor (German: Haida). Both Nový Bor and Kamenický Šenov have their own Glass Museums with many items dating since around 1600. It was especially outstanding in its manufacture of glass in high Baroque style from 1685 to 1750. In the 17th century, Caspar Lehmann, gem cutter to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, adapted to glass the technique of gem engraving with copper and bronze wheels.[citation needed]

Modern glass production

[edit]New processes

[edit]

A very important advance in glass manufacture was the technique of adding lead oxide to the molten glass; this improved the appearance of the glass and made it easier to melt using sea-coal as a furnace fuel. This technique also increased the "working period" of the glass, making it easier to manipulate. The process was first discovered by George Ravenscroft in 1674, who was the first to produce clear lead crystal glassware on an industrial scale. Ravenscroft had the cultural and financial resources necessary to revolutionise the glass trade, allowing England to overtake Venice as the centre of the glass industry in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Seeking to find an alternative to Venetian cristallo, he used flint as a silica source, but his glasses tended to crizzle, developing a network of small cracks destroying its transparency. This was eventually overcome by replacing some of the potash flux with lead oxide to the melt.[50]

He was granted a protective patent in where production and refinement moved from his glasshouse on the Savoy to the seclusion of Henley-on-Thames.[51]

By 1696, after the patent expired, twenty-seven glasshouses in England were producing flint glass and were exporting all over Europe with such success that, in 1746, the British Government imposed a lucrative tax on it. Rather than drastically reduce the lead content of their glass, manufacturers responded by creating highly decorated, smaller, more delicate forms, often with hollow stems, known to collectors today as Excise glasses.[52] The British glass making industry was able to take off with the repeal of the tax in 1845.

Evidence of the use of the blown plate glass method dates back to 1620 in London and was used for mirrors and coach plates. Louis Lucas de Nehou and A. Thevart perfected the process of casting polished plate glass in 1688 in France. Prior to this invention, mirror plates, made from blown "sheet" glass, had been limited in size. De Nehou's process of rolling molten glass poured on an iron table rendered the manufacture of very large plates possible.[53] This method of production was adopted by the English in 1773 at Ravenhead. The polishing process was industrialized around 1800 with the adoption of a steam engine to carry out the grinding and polishing of the cast glass.

Industrial production

[edit]

The use of glass as a building material was heralded by The Crystal Palace of 1851, built by Joseph Paxton to house the Great Exhibition. Paxton's revolutionary new building inspired the public use of glass as a material for domestic and horticultural architecture. In 1832, the British Crown Glass Company (later Chance Brothers) became the first company to adopt the cylinder method to produce sheet glass with the expertise of Georges Bontemps, a famous French glassmaker.[n 4] This glass was produced by blowing long cylinders of glass, which were then cut along the length and then flattened onto a cast-iron table, before being annealed. Plate glass involves the glass being ladled onto a cast-iron bed, where it is rolled into a sheet with an iron roller. The sheet, still soft, is pushed into the open mouth of an annealing tunnel or temperature-controlled oven called a lehr, down which it was carried by a system of rollers.[54] James Hartley introduced the Rolled Plate method in 1847. This allowed a ribbed finish and was often used for extensive glass roofs such as within railway stations.

An early advance in automating glass manufacturing was patented in 1848 by the engineer Henry Bessemer. His system produced a continuous ribbon of flat glass by forming the ribbon between rollers. This was an expensive process, as the surfaces of the glass needed polishing and was later abandoned by its sponsor, Robert Lucas Chance of Chance Brothers, as unviable. Bessemer also introduced an early form of "Float Glass" in 1843, which involved pouring glass onto liquid tin.

In 1887, the mass production of glass was developed by the firm Ashley in Castleford, Yorkshire. This semi-automatic process used machines that were capable of producing 200 standardized bottles per hour, many times quicker than the traditional methods of manufacture.[55] Chance Brothers also introduced the machine rolled patterned glass method in 1888.[56]

In 1898, Pilkington invented Wired Cast glass, where the glass incorporates a strong steel-wire mesh for safety and security. This was commonly given the misnomer "Georgian Wired Glass" but it greatly post-dates the Georgian era.[57] The machine drawn cylinder technique was invented in the US and was the first mechanical method for the drawing of window glass. It was manufactured under licence in the UK by Pilkington from 1910 onwards.

In 1938, the polished plate process was improved by Pilkington which incorporated a double grinding process to give an improved quality to the finish. Between 1953 and 1957, Sir Alastair Pilkington and Kenneth Bickerstaff of the UK's Pilkington Brothers developed the revolutionary float glass process, the first successful commercial application for forming a continuous ribbon of glass using a molten tin bath on which the molten glass flows unhindered under the influence of gravity.[58] This method gave the sheet uniform thickness and very flat surfaces. Modern windows are made from float glass. Most float glass is soda–lime glass, but relatively minor quantities of specialty borosilicate[59] and flat panel display glass are also produced using the float glass process. The success of this process lay in the careful balance of the volume of glass fed onto the bath, where it was flattened by its own weight.[60] Full scale profitable sales of float glass were first achieved in 1960.

Gallery

[edit]-

Glass ear stud, c. 1390–1353 BC, 48.66.30, Brooklyn Museum

-

Phoenician glass necklace 5th–6th century BC

-

Roman glass amphoriskoi 1st–2nd century AD

-

Blue head flask (Roman, AD 300–500, cast glass)

-

Lombardic glass drinking horn 6th–7th century AD

-

Mouth-blown window-glass in Sweden Kosta Glasbruk, (1742) with a pontil mark from the glassblower's pipe

-

Two cups cobalt blue glass with gilt floral decoration from India, Mughal, circa 1700–1775

-

Base for a water pipe, India, Mughal, c. 1700–1775

-

Venetian goblet made in Italy in the early 19th century

-

Bracelets with peacocks, Delhi, enameled silver inlaid with gemstones and glass, 19th century

-

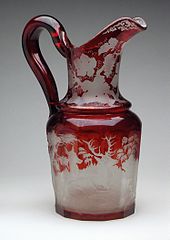

Jug, 1876, James Powell & Sons

-

Siphon bottle for seltzer water, 1922

-

New Martinsville Glass Hostmaster Tea Cup, cobalt blue, 1930

-

Perfume set from Soviet Union, c. 1965

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b True glazing over a ceramic body was not used until many centuries after the production of the first glass.

- ^ Found on the MY Oi 701, MY Oi 702, MY Oi 703 and MY Oi 704 tablets; the least damaged, as far as this word is concerned, is MY Oi 703.[10]

- ^ Cf. κύανος.[11]

- ^ This process was used extensively until early in the 20th Century to make window glass.

References

[edit]- ^ "Glass making may have begun in Egypt, not Mesopotamia Artifacts from Iraq site show less sophisticated technique, color palette". 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ^ a b "Glass Online: The History of Glass". Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ a b c Gowlett, J.A.J. (1997). High Definition Archaeology: Threads Through the Past. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18429-0.

- ^ Lilyquist, Christine (1993). Studies in early Egyptian glass. Robert H. Brill, Mark T. Wypyski. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 23. ISBN 0-87099-683-5. OCLC 28413934.

- ^ These early examples are drawn from Christine Lilyquist (1993). "Granulation and Glass: Chronological and Stylistic Investigations at Selected Sites, ca. 2500-1400 B.C.E.". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 290/291 (290): 29–94. doi:10.2307/1357319. JSTOR 1357319. S2CID 163645343.

- ^ Wilde, H. "Technologische Innovationen im 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Zur Verwendung und Verbreitung neuer Werkstoffe im ostmediterranen Raum". GOF IV, Bd 44, Wiesbaden 2003, 25–26.

- ^ "The Linear B word ku-wa-no-wo-ko". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool for ancient languages.

- ^ Wilde, H. "Technologische Innovationen im 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Zur Verwendung und Verbreitung neuer Werkstoffe im ostmediterranen Raum". GOF IV, Bd 44, Wiesbaden 2003, 25–26 ISBN 3-447-04781-X

- ^ McCray, W. Patrick (2007) Prehistory and history of glassmaking technology, American Ceramic Society, ISBN 1-57498-041-6

- ^ "MY Oi 701 (63)". "MY Oi 702 (64)". "MY Oi 703 (64)". "MY Oi 704 (64)". "Database of Mycenaean at Oslo DĀMOS: publisher: University of Oslo".

- ^ κύανος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ a b "Kielich (flet) z herbami "Pogoń" i "Szreniawa"". muzea.malopolska.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ Reade, Wendy (2021). The First Thousand Years of Glass-Making in the Ancient Near EAst: Compositional Analysis of Late Broze and Iron Age Glasses. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing LTD. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-78969-703-2.

- ^ Douglas, R. W. (1972). A history of glassmaking. Henley-on-Thames: G T Foulis & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-85429-117-2.

- ^ Agricola, Georgius, De re metallica, translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover, Dover Publishing. De Re Metallica Trans. by Hoover Online Version Page 586. Retrieved September 12, 2007

- ^ "Israel Antiquities Authority".

- ^ "Kiln Site in Israel May Have Produced "Judean Glass" - Archaeology Magazine". 11 April 2016.

- ^ Ṣāliḥʹvand, Navīd (2015). Tārīkhchah-i shīshah va shīshahʹgarī : ẓurūf-i shīshahʹī dawrah-i Ashkānī, majmūʻah-i Mūzih-i Millī va Mūzih-i Riz̤ā ʻAbbāsī [The history of glass and glass making : glass vessels of Arsacid era in the collections of Iran National Museum and Reza Abbasi Museum] (in Persian) (Chāp-i avval ed.). [Tihrān]: Samīrā. ISBN 9789648955491. OCLC 933388489.

- ^ a b c d e Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09262-5.

- ^ "The Ancient Indus Valley" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ a b c D.M., Bose, ed. (1971). A Concise History of Science in India. Indian National Science Academy. p. 15. ISBN 8173716196.

- ^ Kanungo, Alok K.; Brill, Robert H. (January 2009). "Kopia, India's First Glassmaking Site: Dating and Chemical Analysis". Journal of Glass Studies. 51: 11–25.

- ^ Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). "Ornaments, Gems etc. (Ch. 10)". An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09262-5.

- ^ Braghin, C. (2002) "Introduction" pp. XI-XIV in Braghin, C. (ed) Chinese Glass. Archaeological studies on the uses and social contest of glass artefacts from the Warring States to the Northern Song Period (fifth century B.C. to twelfth century A.D.). ISBN 8822251628.

- ^ a b Pinder-Wilson, R. (1991) "The Islamic lands and China" p. 140 in Tait, H. (ed) Five thousand years of glass. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ Braghin, C. (2002) "Polychrome and monochrome glass of the Warring States and Han periods" p. 6 in Braghin, C. (ed) Chinese Glass. Archaeological studies on the uses and social contest of glass artefacts from the Warring States to the Northern Song Period (fifth century B.C. to twelfth century A.D.). ISBN 8822251628

- ^ Kerr, R. and Wood, N. (2004) "Part XII: Ceramic technology" pp. 474–477 in Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521838339

- ^ An Jiayao (2002) "Polychrome and monochrome glass of the Warring States and Han periods" pp. 45–46 in Braghin, C. (ed) Chinese Glass. Archaeological studies on the uses and social contest of glass artefacts from the Warring States to the Northern Song Period (fifth century B.C. to twelfth century A.D.). ISBN 8822251628.

- ^ Jenyns, R. (1981) Chinese Art III: Textiles, Glass and Painting on Glass. Phaidon Press

- ^ Whitehouse, David; Glass, Corning Museum of (May 2004). Roman Glass in the Corning Museum of Glass. Hudson Hills. ISBN 9780872901551.

- ^ The Art Journal. Virtue and Company. 1888.

- ^ The Glass Industry. Ashlee Publishing Company. 1920.

- ^ Fleming, S. J., 1999. Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- ^ Stern, E. M. (1999). "Roman Glassblowing in a Cultural Context". American Journal of Archaeology. 103 (3): 441–484. doi:10.2307/506970. JSTOR 506970. S2CID 193096925.

- ^ Toner, J. P. (2009) Popular culture in ancient Rome. ISBN 0-7456-4310-8. p. 19

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y, Assessment of Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna Archived 2010-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y. The Manufacture of Coloured Glass Archived 2010-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Oliver, Roland Anthony; Fagan, Brian M. (1985). Africa in the iron age: c. 500 B. C. to A. D. 1400 (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20598-6.

- ^ Babalola, Abidemi Babatunde; Dussubieux, Laure; McIntosh, Susan Keech (2018). "Chemical analysis of glass beads from Igbo Olokun, Ile-Ife (SW Nigeria): New light on raw materials, production, and interregional interactions". Journal of Archaeological Science. 90: 92–105. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2017.12.005.

- ^ Donny L. Hamilton. "Glass Conservation". Conservation Research Laboratory, Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ Bayley, J. (2000). "Glass-working in Early Medieval England" pp. 137–142 in Price, J. Glass in Britain and Ireland AD 350–1100. London: British Museum Occasional paper 127. ISBN 0861591275

- ^ a b c d Evison, V. I. (2000). "Glass vessels in England, 400–1100 CE" pp. 47–104 in Price, J. Glass in Britain and Ireland AD 350–1100. London: British Museum Occasional paper 127. ISBN 0861591275

- ^ a b Heyworth, M. (1992) "Evidence for early medieval glass-working in north-western Europe" pp. 169–174 in S. Jennings and A. Vince (eds) Medieval Europe 1992: Volume 3 Technology and Innovation. York: Medieval Europe 1992

- ^ Ecclesiastical: Of or relating to a church or to an established religion.

- ^ Harden, D. B. (1978). "Anglo-Saxon and later Medieval glass in Britain: Some recent developments" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 22: 1–24. doi:10.1080/00766097.1978.11735405.

- ^ Bimson M. and Freestone, I.C. (2000). "Analysis of some glass from Anglo-Saxon Jewellery" pp. 137–142 in Price, J. Glass in Britain and Ireland AD 350–1100. London: British Museum Occasional paper 127. ISBN 0861591275

- ^ Bimson, M. (1978) "Coloured glass and millefiori in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial". In Annales du 7e congrès international d'etude historique du verre: Berlin, Leipzig, 15–21 August 1977: Liège: Editions du Secretariat Général.

- ^ Georg Agricola De Natura Fossilium, Textbook of Mineralogy, M.C. Bandy, J. Bandy, Mineralogical Society of America, 1955, p. 111 Section on Murano Glass, De Natura Fossilium. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ inc, Encyclopaedia Britannica (1992). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 9780852295533.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Newton, Roy G.; Sandra Davison (1989). Conservation of Glass. Butterworth – Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology. London: Butterworths. ISBN 0-408-10623-9.

- ^ MacLeod, Christine (1987). "Accident or Design? George Ravenscroft's Patent and the Invention of Lead-Crystal Glass". Technology and Culture. 28 (4): 776–803. doi:10.2307/3105182. JSTOR 3105182. S2CID 112031479.

- ^ Hurst-Vose, Ruth (1980). Glass. Collins Archaeology. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211379-1.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

- ^ Bontemps on Glassmaking: the Guide du Verrier of Georges Bontemps, translated by Michael Cable (2008). Society of Glass Technology. ISBN 0900682604

- ^ Buch Polak, Ada (1975). Glass: its tradition and its makers. Putnam. p. 169. ISBN 9780399115233.

- ^ "Chance Brothers and Co". Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ Practical Building Conservation: Glass and glazing. Ashgate Publishing. 2011. p. 468. ISBN 9780754645573.

- ^ Pilkington, L. A. B. (1969). "Review Lecture. The Float Glass Process". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 314 (1516). The Royal Society: 1–25. Bibcode:1969RSPSA.314....1P. doi:10.1098/rspa.1969.0212. JSTOR 2416528. S2CID 109981215.

- ^ "Borosilikatglas BOROFLOAT®" Archived 2009-05-05 at the Wayback Machine. SCHOTT AG.

- ^ Bickerstaff, Kenneth and Pilkington, Lionel A B U.S. patent 2,911,759 "Manufacture of flat glass". Priority date December 10, 1953

Further reading

[edit]- Carboni, Stefano; Whitehouse, David (2001). Glass of the sultans. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870999869.