Girolamo Li Causi

Girolamo Li Causi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Italian Senate | |

| In office 4 June 1968 – 24 May 1972 | |

| Constituency | Piazza Armerina |

| In office 8 May 1948 – 24 June 1953 | |

| Member of the Italian Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 25 June 1948 – 4 June 1968 | |

| Constituency | Sicily |

| Member of the Italian Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 June 1946 – 31 January 1948 | |

| Constituency | At-large |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 January 1896 Termini Imerese, Italy |

| Died | 14 April 1977 (aged 81) Rome, Italy |

| Political party | PSI (until 1924) PCdI (1924–1943) PCI (1943–1977) |

| Occupation | Politician, journalist |

Girolamo Li Causi (1 January 1896 – 14 April 1977) was an Italian politician and a leader of the Italian Communist Party who was a prominent figure in the struggle for land reform and against the Mafia in Sicily. He labelled large estates (the latifondi) Sicily's central problem.[1]

Political activist

[edit]Li Causi was born in Termini Imerese, a town in the province of Palermo on the northern coast of Sicily. The son of a shoemaker, he graduated with an economics degree from the University of Venice in northern Italy. As a student, he joined the Italian Socialist Party (Partito Socialista Italiano; PSI).[2]

Forced to leave Venice by the Fascists after Mussolini's March on Rome in October 1922, he went to Rome and then Milan, where he helped organise the Third Internationalist faction of the PSI. In the summer of 1924 he joined the Communist Party of Italy (Partito Comunista d'Italia; PCdI), becoming part of the editorial staff of the Communist newspaper l'Unità and the magazine Pagine rosse.[2][3] After the failed assassination attempt on the fascist prime minister Benito Mussolini in September 1926, the PCdI was outlawed and the publication of l'Unità suppressed. A clandestine edition resumed on the first day of 1927 in which Li Causi was actively involved.[4]

Resisting fascism

[edit]Li Causi became the PCdI interregional secretary in Piedmont and Liguria, where he succeeded in producing clandestine copies of l'Unità and in helping organise rice workers' strikes in Piedmont. He fled to Paris in mid-1927, but was arrested on 10 May 1928 in Pisa during one of his clandestine return trips. Li Causi was sentenced to 20 years and nine months in prison. In 1937, as the result of a political amnesty, he was released from prison and banished to the penal colony on the island of Ponza. When Mussolini was forced to resign on 25 July 1943 Li Causi stayed in the penal colony on the island of Ventotene, 40 kilometres to the east of Ponza.[2][3]

After his release, he went north to join the resistance against the German occupation and remaining Italian fascists.[5] By this time the PCdI had been renamed as the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano; PCI), and shortly thereafter Li Causi was made the party's representative on the National Liberation Committee for Upper Italy in Milan, where he was active in producing l'Unità clandestinely and in organising the resistance. Li Causi became a member of the national directorate of the PCI that was reinstated on 29 August 1943 in Rome.[2][6]

Back to Sicily

[edit]The PCI directorate sent Li Causi to Sicily to reinforce the party with an experienced leader. He arrived in Palermo on 10 August 1944.[7] Although the PCI – traditionally weak in Sicily – included a separatist faction, Li Causi successfully urged the Communists to maintain a strong anti-separatist stance, and by late 1944 Communists and separatists were doing battle in the streets.[8]

Li Causi's arrival in Sicily marked a change in Communist fortunes on the island. He worked to curb dissension, prevent violence, and block Sicilian separatism while supporting autonomy. Li Causi believed that Sicilians would benefit from autonomy. Separatism, which represented a "vague sentimental attitude" that the island's reactionaries supported, would only cause harm. Li Causi became the main rival of separatist leader Finocchiaro Aprile and the most consistent enemy of separatism.[1]

The Villalba attack

[edit]On 16 September 1944 Li Causi and the local socialist leader Michele Pantaleone, as leaders of the Blocco del popolo in Sicily, gave a speech to landless peasants at an election rally in Villalba, the personal fiefdom of Mafia boss Calogero Vizzini. In the morning tensions rose when Christian Democrat mayor Beniamino Farina – a relative of Vizzini as well as his successor as mayor – angered local Communists by ordering all hammer-and-sickle signs to be taken down from buildings along the road on which Li Causi would travel into town. When his supporters protested, they were intimidated by separatists and thugs.[9]

The rally began in the late afternoon. Vizzini had agreed to permit the meeting and assured them there would be no trouble as long as local issues, land problems, the large estates, or the Mafia were not addressed. While the speakers who preceded Li Causi, including Pantaleone, followed this, Li Causi did not, and denounced the unjust exploitation at the hands of the Mafia. When Li Causi started speaking about how the peasants were being deceived by "a powerful leaseholder" – a thinly disguised reference to Vizzini – the Mafia boss shouted: "It's a lie". A shoot-out started, which left 14 people wounded including Li Causi and Pantaleone.[7][9][10][11][12] During the incident Li Causi shouted at one of the peasant attackers: "Why are you shooting, who are you shooting at? Can't you see that you're shooting at yourself?"[13]

Vizzini and his bodyguard were subsequently charged with attempted manslaughter. The trial dragged on until 1958, but by 1946 all evidence had disappeared. Vizzini was never convicted because, by the time of the verdict, he was already dead.[11]

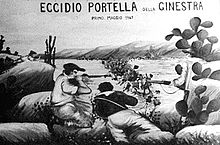

1947 Sicily election and the Portella della Ginestra massacre

[edit]The Villalba shooting was the first of a series of Mafia attacks against political activists, trade union leaders, and peasants resisting Mafia rule and claiming land titles.[9] In the following years many left-wing leaders were killed or injured. On 20–21 April 1947 the Blocco del popolo – a coalition of the Communist and Socialist parties – achieved a surprising result in Sicily's regional elections, winning a plurality of seats with 30.4% of the vote, while the (Christian Democracy) got 20.5% and the Common Man-Monarchist bloc came third with 14.8%.

Commenting on the success of the left-wing alliance, Li Causi said:

For the Communist Party, there is no question of world revolution, but of feeding and democratising the people. We plan no Soviet here. We want the big feudal land holdings redistributed, but we respect all properties below 100 hectares [247 acres]. And that is a good-sized piece of property. We want industry ... . We want to put the idle to work. Capital will find all the guarantee it needs.[14]

Twelve days after the elections a crowd of Communist and Socialist peasants celebrating May Day in Portella della Ginestra was attacked, leaving 11 people dead and 27 wounded. While the attack was officially attributed to Salvatore Giuliano, bandit and former separatist leader, the Mafia was suspected of involvement in the massacre.[15]

The Communist-controlled Italian General Confederation of Labour called a general strike in protest against the massacre. The Minister of the Interior, the Christian Democrat Mario Scelba, reported to Parliament the next day that so far as the police could determine, the Portella della Ginestra shooting was non-political. Scelba claimed that bandits notoriously infested the valley in which it occurred.[5][15] Li Causi disagreed and claimed that the Mafia had perpetrated the attack, in cahoots with the large landowners, monarchists and the rightist Common Man's Front. The debate ended in a fistfight between left-wing and right-wing Members of the Constituent Assembly, to which nearly 200 deputies took part.[15]

Li Causi and Scelba would be the main opponents in the aftermath of the massacre and the successive killing of the alleged perpetrator, the bandit Salvatore Giuliano, and the trial against Gaspare Pisciotta and other remaining members of Giuliano's gang. While Scelba dismissed any political motive, Li Causi stressed the political nature of the massacre. Li Causi claimed that the police inspector Ettore Messana – who was supposed to coordinate the prosecution of the bandits – had been in league with Giuliano and denounced Scelba for allowing Messana to remain in office. Later documents would prove this accusation.[16]

Li Causi also suspected a wider campaign against the left, linking it with the crisis in the national government (then led by Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi), which saw the expulsion of Communists and Socialists from the government coalition, and which would also intended to prevent them from forming the regional government in Sicily. On 30 May 1947, the Christian Democrat Giuseppe Alessi was sworn in as President of the Sicilian region with the support of right-wing parties, while De Gasperi announced his new centrist government, from which the left was excluded for the first time since 1944.[17]

Challenging Giuliano

[edit]

Speaking at Portella della Ginestra on the second anniversary of the massacre, Li Causi publicly called on Giuliano to name names. He received a written reply from the bandit leader: "It is only men with no shame who give out names. Not a man who tends to take justice into his own hands; who aims to keep his reputation in society high, and who values this aim more than his own life."

Li Causi responded by reminding Giuliano that he would almost certainly be betrayed: "Don't you understand that Scelba will have you killed." Giuliano again replied, hinting at the powerful secrets that he possessed: "I know that Scelba wants to have me killed; he wants to have me killed because I keep a nightmare hanging over him. I can make sure he is brought to account for actions that, if revealed, would destroy his political career and end his life."[18][19]

At the trial for the Portella della Ginestra massacre, Gaspare Pisciotta said: "Those who have made promises to us are called Bernardo Mattarella, Prince Alliata, the monarchist MP Marchesano and also Signor Scelba, Minister for Home Affairs ... it was Marchesano, Prince Alliata and Bernardo Mattarella who ordered the massacre of Portella di Ginestra. Before the massacre they met Giuliano". However, the MPs Mattarella, Alliata and Marchesano were declared innocent by the Court of Appeal of Palermo, at a trial which dealt with their alleged role in the event.[16][20]

In Parliament

[edit]

Li Causi was a member of the Italian Constituent Assembly in 1946 and a Senator from 1948 to 1953 and 1968–74, as well as national deputy in 1953-68 and vice-president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies in 1958–63. While in Parliament he was largely responsible for setting up a parliamentary commission of enquiry into the Mafia, and was vice-president of the Antimafia Commission from 1963 to 1972.

In an interview in the 1970s, he said about the changes in the Mafia:

the Mafia has changed; the old sources of wealth, the rackets of cattle-stealing, water control are no longer so lucrative. Real-estate speculation, banks, the trading of jobs and collusion with the power of the State: these are the Mafia's new fields. The Mafia goes where the power is, that is why the Christian Democrat party is riddled with it, not only on the regional level. The high protectors, the ones elected through the power of the Mafia, are in Rome.[21]

Although Li Causi was a prominent Communist leader, his career was thwarted by party secretary Palmiro Togliatti. Togliatti underestimated the problem of the Mafia, or rather, ignored it, and preferred to avoid Sicily becoming a source of irreparable confrontation between the Communists and Christian Democrats, whose Sicilian notables were sometimes contiguous to the Mafia, and some of whom also were prominent on a national level. Togliatti did not hesitate to replace Li Causi as regional secretary of the Party in the late 1950s, at a time when the Mafia increased its rule in rural areas as well as cities.[22]

Li Causi remained an important parliamentary leader at the national level. He died in Rome on 14 April 1977. A year before he died he typically fought his last legal battle. He denounced the responsibility of Giovanni Gioia – at the time the regional secretary of the Christian Democrats in Sicily – in the murder of Pasquale Almerico, the young secretary of the DC in Camporeale who had opposed the entrance of Mafia boss Vanni Sacco in the DC. He also accused another Christian Democrat politician, Vito Ciancimino, of being the centre of a web of business and Mafia in Palermo administered by the DC. He was sued for libel by both. He showed up in court. He spoke at length and was acquitted in both cases.[22]

Speeches and books

[edit]- (in Italian) Intervento di Girolamo Li Causi Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine alla Assemblea Costituente, seduta del 15 luglio 1947

- (in Italian) Intervento alla camera dei deputati at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 June 2008) di Girolamo Li Causi, seduta del 26 ottobre 1951

- (in Italian) Li Causi, Girolamo (1974). Il Lungo cammino: autobiografia 1906-1944, Rome: Editori Riuniti

- (in Italian) Li Causi, Girolamo (2007). Portella della Ginestra. La ricerca della verità , Ediesse, ISBN 88-230-1201-5

References

[edit]- ^ a b Finkelstein, Separatism, the Allies and the Mafia, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Lane, Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders, p. 571

- ^ a b (in Italian) Biografie Assamblea costituente[permanent dead link]

- ^ (in Italian) L'Unità, storia di un quotidiano antifascista

- ^ a b (in Italian) Li Causi, l'uomo che denunciò al mondo Portella, Liberazione, 1 May 2007

- ^ (in Italian) I Centenari CGIL Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b (in Italian) Il «battesimo del fuoco» di Li Causi, La Sicilia, 24 June 2007

- ^ "Review of: Separatism, the Allies and the Mafia: The Struggle for Sicilian Independence, 1943- 1948". Archived from the original on 31 January 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) in The Italian American Review, Volume 7, Number 1 (Spring/Summer 1999) - ^ a b c Finkelstein, Separatism, the Allies and the Mafia, p. 95-97

- ^ "L'attentato di Villalba" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2009., preface of Carlo Levi in Michele Pantaleone, Mafia e politica 1943-1962, Turin: Einaudi, 1962)

- ^ a b Servadio, Mafioso, p. 99

- ^ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 245-48

- ^ Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 190

- ^ "Caesar with Palm Branch". Time. 5 May 1947. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c "Battle of the Inkpots". Time. 12 May 1947. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Servadio, Mafioso, p. 128-29

- ^ (in Italian) Santino, La strage di Portella, la democrazia bloccata e il doppio stato Archived 22 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 265-66

- ^ "Lettera di Giuliano a "La Voce di Sicilia", 31 agosto 1947, e commento-risposta di Girolamo Li Causi" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Mario Scelba: padre della Repubblica o regista di trame?" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) at Giuliano e lo Stato, an Italian language site about Giuliano and the Portella della Ginestra massacre. - ^ Servadio, Mafioso, p. 211

- ^ a b (in Italian) Valeva la pena di conoscerli. Girolamo Li Causi, Notizie radicali, 12 January 2010

Sources

[edit]- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Finkelstein, Monte S. (1998). Separatism, the Allies and the Mafia: The Struggle for Sicilian Independence, 1943-1948, Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press ISBN 0-934223-51-3

- Lane, A. Thomas (1995). Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders, London/Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood Press ISBN 0-313-26456-2

- Lupo, Salvatore (2009). History of the Mafia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13134-6

- (in Italian) Santino, Umberto (1997). La strage di Portella, la democrazia bloccata e il doppio stato, Centro Siciliano di Documentazione "Giuseppe Impastato", April 1997

- Servadio, Gaia (1976), Mafioso. A history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-436-44700-2

External links

[edit]- (in Italian) Girolamo Li Causi, Portale storico della Camera dei deputati

- (in Italian) Giuliano e lo Stato: materiali sul primo intrigo della Repubblica at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 June 2008) an Italian language site about Giuliano and the Portella della Ginestra massacre.

- 1896 births

- 1979 deaths

- People from Termini Imerese

- Italian Socialist Party politicians

- Italian Communist Party politicians

- Members of the National Council (Italy)

- Members of the Constituent Assembly of Italy

- Senators of Legislature I of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature II of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature III of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature IV of Italy

- Senators of Legislature V of Italy

- Antimafia

- Politicians from the Metropolitan City of Palermo

- L'Unità editors