German occupation of Crimea during World War II

Generalbezirk Krym-Taurien | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1944 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Horst-Wessel-Lied | |||||||||

Crimea in 1942 (Dark green) – Within Reichskommissariat Ukraine (light green) | |||||||||

| Status | District of Reichskommissariat Ukraine under military occupation | ||||||||

| Capital | Simferopol | ||||||||

| Common languages | German (official) Crimean Tatar · Ukrainian · Russian · Mariupol Greek · Karaim | ||||||||

| Government | Military administration of Nazi Germany | ||||||||

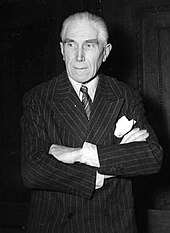

• General Commissar | Alfred Frauenfeld (Projected) | ||||||||

• Field Marshal |

| ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

| 22 June 1941 | |||||||||

• Established | 18 October 1941 | ||||||||

• Crimea recaptured by the Soviet Union | 12 May 1944 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 27,000 km2 (10,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Karbovanets | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Crimea | ||||||||

During World War II, the Crimean Peninsula was subject to military administration by Nazi Germany following the success of the Crimean campaign. Officially part of Generalbezirk Krym-Taurien, an administrative division of Reichskommissariat Ukraine, Crimea proper never actually became part of the Generalbezirk, and was instead subordinate to a military administration. This administration was first headed by Erich von Manstein in his capacity as commander of the 11th Army and then by Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist as commander of Army Group A.

German interests in Crimea were multifaceted and a matter of great sensitivity due to German–Turkish relations, with Turkey serving as the primary champion of the rights of Crimean Tatars. Basing their interests in Crimea off of the historical existence of the Crimean Goths (the last surviving Gothic peoples), German authorities sought to transform Crimea into a tourist destination, including the deportation and genocide of Crimea's non-German inhabitants. Plagued by Soviet resistance from the outset of occupation, they failed to establish order to any extent that allowed for colonisation to take place, and lost further support due to the slow pace of land reform programmes and a lack of response to Crimean Tatar nationalist sentiment.

A matter of significant strategic and ideological importance, Germany's occupation of Crimea remained a matter of hot debate between the Wehrmacht, NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs, and Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. It was variously proposed to be annexed into Reichskommissariat Ukraine, made part of Germany proper, or transformed into an independent state under German suzerainty. Collaboration by some Crimean Tatars during the German occupation served as the basis for the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944, despite active Crimean Tatar participation in the war effort and the desire by certain sectors of the German government to deport Tatars themselves.

Background

[edit]Crimean Tatars against the Soviet government

[edit]Prior to Operation Barbarossa, Crimea operated as an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union. Though Crimean Tatars, a Turkic and religiously-Muslim ethnic group, were the eponymous people and a significant portion of the population, tensions existed between them and ethnic Slavs (primarily Russians). These tensions were compounded by Soviet government opposition to expressions of Crimean Tatar national desires, such as a government-backed proposal for Jewish autonomy in Crimea in the early 1920s, the arrest and execution of national communist leader Veli İbraimov in 1928, and the mass killings of Crimean Tatar leaders during the Great Purge in the late 1930s. These tensions were used by German occupational forces as a method of driving a wedge between Crimean Tatars and other ethnic groups, including Jews.[1]

Crimea's Germanic peoples

[edit]In addition to local conflicts which preceded Germany's occupation of Crimea in 1941, the region had historically been home to a significant Germanic population. The Crimean Goths, the final surviving Gothic group, survived in Crimea from the 3rd century CE until at least c. 1780[2] and possibly still existed by the time of World War II, though they intermingled with Crimean Tatars much like other ethnic groups.[3] According to the Nazis, these Goths had existed long enough to intermingle with the later Crimea Germans,[4] settlers who began arriving as part of the migrations of the late-18th century with the support of the German-born Russian Empress Catherine the Great. Later, Mennonites began arriving from Russia and Ukraine proper.[5][failed verification]

By the time of the Russian Revolution of 1917, Crimean Germans made up the local élite, comprising 20% of the Simferopol city council.[6] German had the right to organise local self-government in their settlements, and were free from paying taxes.[5] German had been one of the official languages of the Crimean Regional Government of 1918-1919, which was established with the support of German forces during World War I.[7] Following the 1920 takeover of Crimea by the Red Army, the Soviets established two German raions within the Crimean ASSR; Büyük Onlar Raion (in 1930) and Telman Raion. Despite this, however, after the Axis Powers launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Soviet authorities from August 1941 deported over 60,000 ethnic Germans from Crimea; "evacuating" them eventually to Siberia or to Central Asia.[8][9]

German–Turkish relations

[edit]Matters involving Crimea were a focal point of German–Turkish relations during World War II. Turkish interests in Crimea, stretching back to the early days of the Ottoman Empire, primarily involved the protection of the Crimean Tatars. Following the dissolution of the Crimean People's Republic at the hands of the Red Army, Turkey had become a base for many Crimean Tatar nationalists, among them Cafer Seydamet Qırımer, the Crimean People's Republic's Prime Minister. Though Turkish interests also concerned themselves with additional areas of the Soviet Union inhabited by Turkic peoples, Crimea held the most Turkish public and governmental interest of all regions.[10]

Timeline

[edit]1941

[edit]

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941, thus drawing the Soviet Union into World War II. By 26 September 1941, German forces, supported by the Kingdom of Romania, had started fighting for Crimea, beginning the Crimean campaign.[11] Consecutively with the entrance of German troops, structures by Soviet forces for the development of a partisan movement were established in the city of Kerch, in the eastern Kerch Peninsula.[12] In the winter of 1941, Soviet forces landed in the Kerch Peninsula over the Kerch Strait, in what became known as the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula.[13]

Even prior to the beginning of Germany's occupation of Crimea, German leadership had already begun planning for the colonisation of the peninsula. In a directive dating to early July 1941, Hitler called for the immediate expulsion of all Russians from the peninsula, with Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars only to be removed in case of absolute necessity. This measure, explicitly outlining the protection of Crimean Tatars from deportation, demonstrated to the Turkish government Germany's willingness to protect their interests.[14] Turkey, not pleased with the level of autonomy granted, made continuous demands (both subtle and overt) through Franz von Papen, Germany's ambassador to Turkey. After much lobbying and the intervention of Turkish general Hüseyin Hüsnü Emir Erkilet, two followers of Seydamet Qırımer were granted visas to enter Turkey. The process of granting visas, done during a period when Germans intended to ethnically cleanse Crimean Tatars in the near future, was deliberate, and the Crimean Tatars were not granted requests to inspect Crimean prisoner of war camps. Nonetheless, following the visit, Rosenberg noted that it would be necessary to ensure Crimean Tatar prisoners of war be treated humanely out of respect for Turkey.[10]

The first commander of German occupational forces in Crimea was Erich von Manstein. Manstein declared upon taking command that, "The Jewish-Bolshevik system must be wiped out once and for all." With this began the recruitment of Crimean Tatars to serve as anti-partisan volunteer detachments under the aegis of the Sicherheitsdienst.[15] Another element of collaboration was local-level "Muslim Committees", established as a compromise between pro-Turkic voices and the Wehrmacht, which viewed Crimean Tatars as insignificant in comparison to Crimea's Slavic majority.[16]

1942

[edit]

The end of the Crimean campaign brought little stability to Germany's occupational regime, with the partisan movement only continuing its activities. The groundwork of Crimea's colonisation by German settlers began being laid in early 1942, though it remains unknown exactly when. The same year, preparations also began in earnest for the genocide of Crimea's peoples. On 6 July 1942, in spite of previous protests against the liquidation of Crimea's Russian population (for economic reasons), officials the Wehrmacht participated in a conference with Schutzstaffel members on resettlement camps, the genocide of "untermenschen", and the establishment of transport facilities for deported peoples.[14]

Despite the support of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht for these plans, individual officers still disputed them, along with resettlement plans, as unhelpful to the war effort. General Georg Thomas protested to Hermann Göring and field marshal Wilhelm Keitel, noting that Alfred Frauenfeld, Crimea's General Commissioner, was also opposed to deportation during the war. Three weeks later, he was told that the plans for colonisation and deportation had been halted until the war's end.[14]

In late 1942, Manstein was replaced by Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist as commander of German forces in Crimea. Alongside his position as commander of forces in Crimea, Kleist was involved in the Battle of the Caucasus, and his attitudes towards the North Caucasian peoples served as a basis for later activity he conducted in regards to the Crimean Tatars.[17]

Another noteworthy development in 1942 was the establishment of the Simferopol Muslim Committee, which served as a central organisational authority for Crimea's Muslim Committees.[16] These committees in late 1942 established a plenum with the intention of representing all Crimean Tatars. They elected Amet Özenbaşlı as their leader, and granted him broad permission to negotiate with the Germans on behalf of the Crimean Tatar people. However, the election of Özenbaşlı as the Muslim Committees' representative was followed only by further hesitation on the part of German authorities when dealing with the Crimean Tatars, leading Özenbaşlı to remark in 1943, "We have found ourselves between Scylla and Charybdis." Such sentiment was widespread among nationalist circles, as Germany's unclear attitude and gains by the Red Army led to increased feelings of consternation. Also negatively affecting the German-Tatar relationship was anti-partisan reprisals against Crimean Tatar villages. Özenbaşlı made an unsuccessful effort to effectively rebuild Milliy Firqa, the leading party of the Crimean Tatars during the Russian Revolution.[17]

Taurida

[edit]

On 1 September 1942, the Wehrmacht released the five districts of Generalbezirk Krym-Taurien north of the Isthmus of Perekop to a civilian government which acted as part of Reichskommissariat Ukraine. This administration, based in Melitopol and headed by the Generalbezirk's de jure General Commissioner Alfred Frauenfeld, was simply referred to as "Taurida" (German: Taurien). Frauenfeld soon found himself embroiled in conflict with the Reichskommissar of Ukraine, Erich Koch, who instituted an economic blockade of with the support of Hitler and Himmler with the intention of starving out the Crimean Tatar population. After the intervention of the Wehrmacht on Frauenfeld's behalf, the blockade was resolved, but tensions between Taurida and the Reichskommissariat as a whole remained, with Koch calling for Taurida's autonomous status to be abolished and Frauenfeld making negative remarks about Koch's performance in correspondence with Rosenberg. Frauenfeld and Koch remained enemies until the war's end, with Frauenfeld continuing to promote himself as a better leader even after Crimea and Taurida were retaken by Red Army forces.[18]

Frauenfeld's regime has been described as having "limited sympathy" towards the Crimean Tatars by American historian Alexander Dallin, and was relatively liberal in regards to its treatment of the indigenous population compared to Koch's brutal "sledge-hammer" policy in regards to non-Germans. During his leadership, Frauenfeld, who held little to no control over Crimea proper, devoted himself to the study of Crimean Goths, creating a photo album and writing a book on Crimea's history. Under Frauenfeld's proposals, Crimea was to become a tourist hotspot for all of post-war Europe, and a new capital was to be built in the Crimean Mountains.[18]

1943 and 1944

[edit]

Following a retreat from the Caucasus, Kleist took a more active role in governing Crimea. In February 1943, he issued a series of 14 points, including the following:

- 1. The inhabitants of the occupied Eastern territories in the area of Army Group 'A' are to be treated as allies. Treatment as inferiors strengthens the enemy's will to resist and costs German blood.

- 2. The supply of the civilian population with food, especially bread, and also clothes, fuel, and consumer goods, is to be improved within the limits imposed by the war...

- 3. Social services are to be expanded, e.g. supply of hospitals with medicines, and milk for women and children.

- 6. In principle, 20 per cent of all consumer goods produced are to be distributed among the civilian population.

- 7. The agrarian reform is to be carried out with greater dispatch. In 1943 at least 50 per cent of the collectives are to be transformed into communes. In the remaining collectives, the individual plots are to be given to the peasants as tax-free property. In appropriate cases individual farms are to be established...

- 8. As a rule ... the delivery quota for agricultural produce shall not exceed that under the Bolsheviks...

- 12. The school system is to be promoted widely.

- 14. Religious practice is free and is not to be impeded in any way...

This newfound interest in Crimea was met with strong resistance from the SS, which regarded Kleist's involvement in civilian affairs as unwelcome. In spite of this resistance, however, Kleist refused to change his position, comparing Hans-Joachim Riecke, one of his strongest detractors, to Koch.[17] Four months later, Rosenberg toured Crimea, speaking to soldiers. Both Kleist and Rosenberg regarded the tour as a failure, but for opposing reasons: Kleist because of what he regarded as overly-negative rhetoric and Rosenberg because he perceived the Wehrmacht as having a decidedly more Russophilic approach towards indigenous affairs than himself.

Throughout 1943, the remaining pretences of maintaining control over Crimea were dropped as Red Army forces closed in on the area; General Ernst August Köstring was placed in charge of inspecting Germany's Turkic military forces, shifting concerns from occupation to maintenance of order. Frauenfeld evacuated Taurida, leaving the area once again under military control. Georg Leibbrandt, in charge of Germany's "nationality policy", was replaced with Gerhard von Mende, who also shifted the focus away from Germany's occupations.[18] By November 1943, Soviet troops returned to the Kerch Strait. They quickly advanced through the Crimean peninsula, and by May 1944, all of Crimea up to the Isthmus of Perekop had been recaptured.

Economics

[edit]Land reform

[edit]With Germany's capture of Crimea, Crimea's peasants anticipated decollectivisation and the return of land, much like in other areas of the Soviet Union under German control. However, the government pursued land reform at a relatively slow pace, a matter which anguished peasants. In accordance with an effort by the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs to appear gracious to Turkey, Hans-Joachim Riecke (Nazi chief of agriculture in Eastern Europe) hastened the pace of decollectivisation, declaring that 40% of Crimean Tatar land would be returned in the first year of land reform. This was significant compared to 10-12% of land in Ukraine, which was to be decollectivised. However, the measure lacked teeth, as land reform efforts did not follow the standards set by the German government.[19] Nonetheless, the land reform was used by Frauenfeld as evidence of greater management in Crimea and Taurida than in Ukraine proper, with particular notice being given to the fact that Crimea had greater production per acre than Ukraine.[18]

Infrastructure

[edit]With Germany's intention to establish Crimea as a leading tourist destination in post-war Europe, numerous infrastructure plans were created in order to make transport to and from Crimea easier. Particularly noted in recent years was a proposal by Hitler to create a bridge across the Kerch Strait. The proposal, which never reached far beyond the planning stages due to Soviet advances, was allocated insufficient resources for its completion, but served as the base for the Kerch railway bridge, a post-war construction which existed for less than a year before collapsing in February 1945. The Crimean Bridge, constructed following the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, has been noted by some publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, for having a similar purpose to Hitler's proposed bridge.[20]

Another project intended to improve Crimea's connections to the rest of Germany's empire was an expansion of the Reichsautobahn to Crimea. The proposal, which never left the drawing board, would have, in Hitler's words, made it so that one could, "do the whole distance easily in two days."[14]

Religion

[edit]

Islam was regarded by German authorities as a method for effective control of the Crimean Tatar population, as well as other Muslim peoples throughout the Soviet Union. This became particularly noteworthy from October 1943, after Soviet authorities established the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM). As an attempt to counteract the establishment of SADUM, German officials organised a congress of Muslims from Crimea, Tatarstan, Central Asia, and the Caucasus, to be overseen by Amin al-Husseini, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. With the support of Gottlob Berger from the SS, Özenbaşlı was to be declared as Crimea's mufti. The Wehrmacht was immediately suspicious of Özenbaşlı, regarding the title as a means for him to assert further control over Crimea, and protested. Rosenberg, unable to fight the protestations by the Wehrmacht, gave up on the project.[21]

Following Crimea's recapture by Soviet forces, the German government again sought to give Özenbaşlı the title of mufti, and requested that he travel to Berlin to be officially appointed. Instead, however, Özenbaşlı fled to Romania in expectation that British troops would take control of the country. However, he was instead captured by Soviet troops and repatriated to the Soviet Union, where he died in 1958.[21]

Future plans

[edit]Plans for Crimea's post-war future remained a topic of debate in the halls of German power until it was ultimately recaptured by Soviet forces. Seven different plans were made by leading Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg, none of which were actually adopted due to the failure of German forces to subdue partisan forces or maintain military control of Crimea. Additionally complicating matters was the matter of German–Turkish relations and Turkish concerns for ethnic Crimean Tatars, which interfered with Germany's intentions for the total colonisation of Crimea.

Inclusion into Reichskommissariat Ukraine

[edit]Rosenberg's first plan, simply titled 'Ukraine with the Crimea', called for Crimea to be included into Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Containing numerous contradictions and undergoing several revisions, it nonetheless became the prevailing plan, and Crimea was de jure included into the Reichskommissariat. At the same time, however, it was to be directly subjugated to German control. The most significant issue of this plan, noted by Rosenberg himself, was the lack of ethnic Ukrainians in Russian-dominated Crimea.[22]

German colonisation

[edit]The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Ostministerium), headed by Rosenberg, took an aggressive position in regards to Crimea's post-war fate.[23] According to the Ostministerium, Crimea was to fall directly under the control of Nazi Germany, rather than being administered through a Reichskommissariat. A consistent part of the German message was that Crimea was to be completely cleansed of non-Germans,[24] only occasionally sparing Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians. In their place were to be German settlers, for whom Crimea was to become a "spa".[22]

Exactly where the colonists were to come from remained debated. Originally was Romania's Transnistria Governorate, comprising formerly-Soviet lands which included 140,000 Germans. After the end of the Crimean campaign, however, another plan developed, intending to settle the peninsula with Germans from the Italian region South Tyrol, in order to resolve Italo-German tensions. This plan, proposed by Frauenfeld, found support with Hitler, who said of the plan, "I think the idea is an excellent one... I think, too, that the Crimea will be both climatically and geographically ideal for the South Tyrolese, and in comparison with their present settlement it will be a real land of milk and honey. Their transfer to the Crimea presents neither physical nor psychological difficulty. All they have to do is to sail down just one German waterway, the Danube, and there they are." However, with partisan activity and the ongoing war impeding the development of a stable, civilian government, this idea, too, never became reality. The third and final proposal, pushed by Frauenfeld and Ulrich Greifelt, called for the 2,000 Germans in Mandatory Palestine to be resettled in Crimea. This idea was rejected by Himmler, who argued for it to be pursued in the spring of 1943 or during "another favourable moment."[14]

Potential independence

[edit]Counter to the Ostministerium, the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs advocated for a relatively moderate position in regards to Crimea, as part of its generally pro-Turkic position in a bid to attract support from Turkey. Werner Otto von Hentig, the leading voice of the Foreign Office on Islamic affairs alongside his assistant Alimcan Idris, served as the representative of the Foreign Office in Crimea from autumn 1941 to summer 1942. During this time, he formulated a plan to bring Muslims to rise up against Soviet rule through an extensive propaganda campaign involving radio broadcasts, pamphlets, and the usage of spokespeople. Hentig believed that the campaign would foment solidarity with Germany's war against the Soviet Union in the Islamic world. Another faction in the Foreign Office was headed by Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, who advocated for Crimean independence, as well as independence for Turkic peoples in the Caucasus. The Ostministerium, staunchly opposed to these plans, successfully sought the removal of the Foreign Office from affairs in Eastern Europe.[23]

As the tide of the war turned, the Ostministerium came to support Crimean independence itself, as part of a larger Georgian-led bloc against the Soviet Union.[23] This proposed Georgian bloc was opposed by Hitler, who stated:

"I don't know about these Georgians. They do not belong to the Turkic peoples... I consider only the Moslems to be reliable... All the others I deem unreliable. For the time being I consider the formation of these battalions of purely Caucasian peoples as very risky, while I don't see any danger in the establishment of purely Moslem units... In spite of all the declarations from Rosenberg and the military, I don't trust the Armenians either."[25]

Resistance

[edit]Before Crimea even came under occupation by German forces, efforts were made to establish a partisan network in the peninsula. Beginning in Kerch in early October, partisan forces existed in all of Crimea by 23 October 1941. In spite of organisational issues,[26] the Crimean resistance managed to pose a significant threat to German activities in Crimea, and was praised by Soviet generals Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Panteleimon Ponomarenko as being a vital part of the war effort.[27][28]

Aftermath

[edit]

The German occupation of Crimea had an immediate impact on Crimea following its recapture by Soviet forces. As part of a general process of ethnically cleansing ethnicities Stalin regarded as unreliable, all Crimean Tatars were deported from the Crimean peninsula to Central Asia and Siberia (primarily Uzbekistan) from 18 to 20 May 1944.[29] The actual reasons for the deportation remain debated, with some arguing that it was to keep minorities out of the Soviet Union's border regions[30] and others stating that it was done as a way of securing access to the Dardanelles strait in Turkey, across the Black Sea from Crimea, as a prelude to the Turkish straits crisis of 1946–1953.[31] Others, still, cast the deportation as an act of Russian nationalism dating back to long before the establishment of the Soviet Union.[32]

Following the war, Crimea was economically and agriculturally devastated as a result of fierce fighting. It was impacted by the Soviet famine of 1946–1947, along with Moldova, the Central Black Earth Region, and parts of Ukraine.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ Tyaglyy, Mikhail (2011). "Antisemitic Docrtine in the Tatar Newspaper Azat Kirim (1942-1944)" (PDF). The Journal of Holocaust Research. 25: 172–175.

- ^ Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum. "The Corpus of Crimean Gothic". University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Schwarz, Ernst (1953). "Die Krimgoten". Saeculum: Jahrbuch für Universalgeschichte. 4. Freiburg im Breisgau: Böhlau Verlag: 156–164.

- ^ Wolfram, Herwig (2001). Die Goten und ihre Geschichte. C.H. Beck.

- ^ a b Verkhovsky, Valery (16 July 2020). "Crimean Germans – who are they?". Voice of Crimea. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Zakharova, Aleksandra (22 May 2018). "Немцы в Крыму: история и современность" [Germans in Crimea: History and Modernity]. Business Crimea (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Obolensky, Vladimir Andreyevich (1988). Моя жизнь. Мои современники [My Life, My Contemporaries] (in Russian). Paris: YMCA-PRESS. p. 598. ISBN 9785995008644.

- ^

Verkhovsky, Valery (16 July 2020) [2017]. "Crimean Germans – who are they?". Crimean Room. No. 13. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

Unlike the Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Armenians, the Crimean Germans were not formally deported from the Crimea. The documents of August 15, 1941, speak only of 'evacuation.' More than 60,000 people were deported to Stavropol and the Rostov region. Later, when Hitler's troops moved on Baku and Stalingrad, these unfortunate people were sent to Siberia and Kazakhstan.

- ^

Pohl, J. Otto (2 October 2008). "Suffering in a Province of Asia: The Russian German Diaspora in Kazakhsta". In Schulze, Mathias; Skidmore, James M.; John, David G.; Liebscher, Grit; Siebel-Achenbach, Sebastian (eds.). German Diasporic Experiences: Identity, Migration, and Loss. WCGS German Studies. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 409–411. ISBN 9781554581313. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

Between September 1941 and January 1942, the Stalin regime deported 385,785 Russian Germans from the Volga, Ukraine, Crimea, the Caucasus, the Kuban, Moscow, Rostov, and Tula to Kazakhstan. [...] the 50,000 Crimean Germans deported to Kazakhstan [...].

- ^ a b Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 257–258. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ Keegan, John. The Times Atlas of the Second World War. New York: Crescent Books. p. 62.

- ^ Makarov, N. I. (1976). Непокорённая земля Российская [The Unconquered Russian Land] (in Russian). Moscow: Politizdat. p. 34.

- ^ Forczyk, Robert (2014). Where the Iron Crosses Grow: The Crimea 1941–44. Oxford: Osprey. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4728-1678-8.

- ^ a b c d e Dallin, Alexander (1957). "People and Pol". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. p. 259. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ a b Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. p. 261. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ a b c Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 262–264. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ a b c d Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 264–266. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ Torry, Harriet (4 March 2014). "Medvedev's Planned Bridge to Crimea Has Long History". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 266–270. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ a b Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941–1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-0-333-21695-8.

- ^ a b c Motadel, David (2014). Islam and Nazi Germany's War. Cambridge, London: Belknap Press. pp. 49–50.

- ^ Office of the U.S. Chief of Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis Criminality (1946). Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume II

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1957). "The Crescent and the Swastika". German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Publishers. p. 251. ISBN 9780333216958.

- ^ Polyakov, V. (2009). Страшная правда о Великой Отечественной. Партизаны без грифа «Секретно» [The Horrible Truths of the Great Patriotic War: Partisans Without Sworn Secrecy] (in Russian). Moscow: Yauza, Eksmo. ISBN 9785699366859.

- ^ Vasilevsky, Alexander (1983). Дело всей жизни [The Work of a Lifetime] (in Russian). Moscow: Politizdat. pp. 377, 409.

- ^ Ponomarenko, Panteleimon (1986). Всенародная борьба в тылу немецко-фашистских захватчиков 1941—1944 [The All-People's Struggle in the Rear of the Nazi Invaders, 1941-1944] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (1991). "Punished Peoples" of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF). New York City. LCCN 91076226.

- ^ Manley, Rebecca (2012). To The Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780801457760. OCLC 979968105.

- ^ Skutsch, Carl (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. p. 1188. ISBN 9781135193881. OCLC 863823479 – via Google Books.

- ^ Potichnyj, Peter J. (1975). "The Struggle of the Crimean Tatars". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 17 (2–3): 302–319. doi:10.1080/00085006.1975.11091411. JSTOR 40866872.

- ^ Wheatcroft, Stephen (August 2012). "The Soviet Famine of 1946–1947, the Weather and Human Agency in Historical Perspective". Europe-Asia Studies: 997 – via ResearchGate.

- 1941 establishments in Russia

- 1941 establishments in Ukraine

- 1944 disestablishments in the Soviet Union

- 1944 disestablishments in Ukraine

- Crimea in World War II

- German military occupations

- Military history of Germany during World War II

- Nazi colonies in Eastern Europe

- Soviet Union in World War II

- States and territories established in 1941

- States and territories disestablished in 1944

- Ukraine in World War II