Gerasimos Contomichalos

Gerasimos Contomichalos | |

|---|---|

|

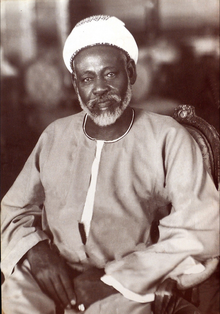

Gerasimos Antonios Contomichalos (Greek: Γεράσιμος Κοντομίχαλος; 4 February 1883[1] – 1 January 1954[2]) was the most eminent business magnate in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the greatest benefactor of the Greek community in Sudan. He wielded considerable political influence both in Sudan and Greece.[1]

Life

[edit]

Contomichalos was born in Argostoli on the Ionian Island of Kefalonia.[1] He left his home in 1899 to pursue his higher education in England, where he stayed for two years doing business management and commercial studies. In 1901 he arrived in Khartoum to assist his uncle Angelo Capato, who was one of the biggest merchants in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan at the time.[3] Contomichalos "worked almost in all branches" of the firm across the country.[4]

In 1904, Capato sent his nephew to the port town of Suakin to manage his trade interests there. According to the Nile Pilot newspaper, Contomichalos convinced the colonial authorities to abandon plans to name the newly constructed harbour city Bandar Sudan and instead call it Port Sudan, "so he is really her godfather."[3]

In 1906/7, Contomichalos was one of the founding members as secretary-general of the Greek Community of Port Sudan, where more than 1,500 Greeks lived at the time, out of a total population of around 7,500, due to large-scale construction works. He later became the President of the association.[1]

In 1908 Contomichalos left his uncle's company and started his own commercial enterprise. He quickly succeeded[3] and expanded into the fields of agriculture, banking, real estate, and ships handling,[4] establishing branches throughout Sudan – with major trade activities in what was then Southern Sudan[1] – as well as in Cairo, London,[5] Eritrea, Ethiopia,[1] Haifa, and Panama.[6] According to a study by the University of Khartoum (UoK), he "monopolized the cotton trade in Khartoum."[7] Meanwhile, Capato's business empire collapsed after a series of misfortunes. Contomichalos supported his uncle's attempts for a commercial comeback and paid him a monthly allowance after another bankruptcy.[5]

According to the Greek anthropologist Gerasimos Makris, who is related to the Greeks of Sudan through marriage, the well-educated Contomichalos "distinguished himself by working hard and methodically." At the same time, he stresses that, "always mindful of developments in the political arena, Contomichalos cultivated his relations with the Government and the Palace".[5] Thus, in 1911, the colonial government granted him a plot of land close to Port Sudan to build a cotton processing factory. One year later he established "The Sudan Trading Co."[1] and entered into a strategic partnership with the London Shipping company to form "Contomichalos and Darke Company", registered in London.[3]

In 1914, Contomichalos moved from Port Sudan to Khartoum[1] where he quickly became a "social magnate" as well.[5] Already one year later, he was elected – like his uncle before – as President of the Greek Community of Khartoum and remained in this office for more than twenty years.[1] Compared to Capato though, as Makris concludes, he "had much more impact than the former – founding churches, schools and other community buildings and offering large sums of money to assist in the establishment of smaller communities in the provinces.”[5]

In 1918, repairs and expansion works at the Greek-Orthodox Church of the Annunciation in Khartoum were started thanks to a large donation by Contomichalos. One year later he was one of the founders of the Greek Community in Wad Madani, since his company was in possession of a large area used for corn cultivation there. Also in 1919, Contomichalos and another Greek businessman, John Cutsuridis, initiated the establishing of the Greek Community in El-Obeid. In 1924, the Greek primary school in Khartoum was re-opened in a new building, which was constructed upon the major initiative of Contomichalos, and named after another Greek pioneer businessman, Panayotis Trampas. In 1935, Contomichalos supported the founding of the Greek Community of Juba with a financial donation – thereby contributing to the creation of the Greek community of South Sudan, which still exists today. In 1942 he gave financial aid to reactivate the Greek Community of Atbara.[1]

Contomichalos also promoted sports, both by establishing a club that addressed his employees and by supporting the Hellenic Athletics Club. In 1937, he furthermore took the initiative to set up the "Charity Brotherhood of the Greek Women in Khartoum-Sudan", which continued to support needy community members with grants for more than three decades.[1]

The Greek historian Alexandros Tsakos writes in his biography of Photini Poulou, who was of Greek and Southern Sudanese origin, that in an interview shortly before her death in 2006 she remembered her days in the Greek school of Khartoum during the 1930s and

"spoke of Mr. Gerasimos through the kindest memories. It must be deeply moving to remember at an old age the man who used to offer accommodation to girls like her; the man who used to provide a weekly ticket to the movies (owned by the Greek family of Lykos, where they could also enjoy a sweet and a lemonade), as well as occasional dinners at one of the Clubs in town... This was one of Photini’s fond memories, especially in her old and sick state, when she was no longer receiving substantial support from those who claim to continue the charitable work of men like Gerasimos Kontomichalos."[8]

In 1928, Contomichalos was awarded the Officer of the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.),[9] and in 1935 the Order of the Nile by King Fuad of Egypt,[1] illustrating the close relationship he maintained with the Anglo-Egyptian regime. Makris writes in this context about Contomichalos' uncle: “Capato – and probably many other Greeks – saw themselves as stalwarts of the 'colonial' order.”[5] Remarkably, Contomichalos was also awarded a Commander of the Legion of Honour by the French Republic.[4]

However, with the emergence of Sudanese nationalism after World War I, Contomichalos started "supporting community leaders with nationalist aspirations"[5] and developed “particularly close” ties with Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, a son of Muhammad Ahmad who had declared himself the Mahdi and defeated the Ottoman-Egyptian rule in 1885.[10] The Greek historian Antonis Chaldeos, who has written his PhD thesis about the history of the Greek community in Sudan, even goes as far as suggesting that Contomichalos was

"the most powerful man in the entire Sudanese territory."[1]

Part of his power was the ownership of press outlets, which made him an early media magnate as well: in 1924, his "Sudan Daily Herald Ltd." started publishing the "Sudan Chronicles", a weekly paper of four pages in Greek, renamed "Sudan News" in 1944.[1] In 1935, Contomichalos became a major shareholder in a company that started publishing the "Al-Nil" daily newspaper, along with al-Mahdi, a British businessman, and Mustafa Aboulela, a merchant of Egyptian origin. According to the UoK study, the paper "continued to be censored daily" and Contomichalos' representative had a recalcitrant editor fired in 1938, making it a "propaganda medium" of the colonial regime. Contomichalos transferred his shares in 1945 to al-Mahdi.[7]

During the early 1930s, Contomichalos was the president of the Khartoum and Sudanese Chambers of Commerce respectively.[11]

Moreover, Contomichalos wielded considerable influence on politics in Greece as well, since he entertained a "close relationship" with Eleftherios Venizelos, the eminent Greek Liberal leader. Already during World War I, Contomichalos had supported Venizelos in his power struggle with King Constantine, who favoured an alliance with the Central Powers, and secured the following of the Greek community in Sudan.[1] His support included financial assistance to the liberal-democratic statesman.[12] These intimate ties also led to the establishment of an air connection between Sudan and Greece in the early 1930s, which had been a major priority for many Greeks in Sudan.[1]

In 1935, it seems that Contomichalos literally played the role of kingmaker: The Nile Pilot claims that "he was the one who reinstated royalism in Greece".[3] According to Greek historians, he was invited by James Henry Thomas, the Secretary of State for the Colonies of the National Government of the United Kingdom, and successfully mediated between General Georgios Kondylis, a former Venizelist who had overthrown the government in October of that year, and King George II of Greece in his London exile.[13] In 1936, shortly after he had regained his throne, the King endorsed the conservative totalitarian and staunchly anti-communist 4th of August Regime under the leadership of General Ioannis Metaxas. The same year, Contomichalos was awarded with the medals of the Grand Commander of the Order of George I and of the Order of the Phoenix, the Silver Cross of Order of the Redeemer, and the Medal of Outstanding Acts. He was also honoured by the Patriarchate of Alexandria with the Order of St. Mark's and by the Patriarchate of Jerusalem with the Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulcher.[1]

While the Metaxas Regime took inspiration from Fascist Italy, Contomichalos advocated for a cooperation with the Fascist Italian regime in Ethiopia after the 1935/36 Second Italo-Ethiopian War started by dictator Benito Mussolini. Contomichalos' interest was the promotion of trade through Kassala, where almost one hundred Greeks lived at the time, and Gedaref, where his own company branch was active in the cross-border trade.[1] In 1937, Contomichalos made arrangements with the Italian authorities to ship over 10,000 tons of trade goods into Gambella.[14]

After World War II, Contomichalos apparently played a key role in paving the way to Sudan's independence: according to the Nile Pilot newspaper, "he played his cards well in smoothing the path of negotiations between the Sudanese and Egypt in 1951."[3]

Shortly before his death, Contomichalos offered a large sum for the restoration of the holy temple of Saint Gerasimos – the patron saint of Kefalonia, after whom Contomichalos was named – near his birthplace of Argostoli. The monastery had collapsed in the devastating 1953 Ionian earthquake.[1]

In private life, according to Makris, Contomichalos – remembered in his family as "G.A.C." after his initials – "had the good fortune to marry a beautiful and extremely rich Greek lady" from Alexandria, since there was a sizeable community of Greeks in Egypt :[5] Catherine, née Haicalis (1886–1966), was the daughter of Nicolas Haicalis,[15] the editor-proprietor of an important newspaper, "whose friendship with the Khedive Ismail in the 1860s had earned him the title of Bey."[16] The couple had six sons and two daughters.[3] Their daughter Alexandra Joanna married John Francis Yarde-Buller, 5th Baron Churston in 1973.[17]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1954, the year that Contomichalos passed away, his son Eleftherios donated on behalf of the family a substantial amount of money to expand the primary Trampeios School. The Kontomichaleios High School and Lyceum was opened in 1957, one year after Sudan's independence. More than half a century later, as the Greek government stopped supporting the school due to the imposition of austerity measures by the European Union, it was transferred to the Confluence International School with some Greek teachers.[1]

One year after the 1969 coup d'état, "Contomichalos and Sons" was placed under sequastration by the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry.[18] It is unclear whether or when this was lifted, but in later years the company continued to operate.[19] The Contomichalos family has kept business interests in Sudan in more recent years as well.[20]

Makris concludes that

"If Capato represented the colourful and adventurous past of the Greek presence in the Sudan, Contomichalos personified the accomplishments of the mature community."[5]

Chaldeos argues that the life achievement of the "emblematic" magnate was

"his great contribution to the progress, development, and prosperity of the country".[4]

A street in downtown Khartoum is named after Contomichalos, illustrating his outstanding status in the modern history of Sudan.[4]

Likewise, a street in his birth town of Argostoli is named after Contomichalos.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Chaldeos, Antonis (2017). The Greek community in Sudan (19th–21st cen.). Athens. pp. 100–101, 105–106, 108, 111, 115, 121, 131, 136–137, 162–173, 185, 187, 191–193, 228, 237, 240, 243, 247, 249–250. ISBN 978-618-82334-5-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Contomichalos, Philip (12 December 2014). "Gerassimos A. Contomichalos". Geni. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bashery, M.O. (January 6, 1966). "PROFILE – G. A. CONTOMICHALOS (1883–1954)". Nile Pilot.

- ^ a b c d e Chaldeos, Antonios (2017). "Sudanese toponyms related to Greek entrepreneurial activity". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4, Art. 1 – via DigitalCommons@Fairfield.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Makris, Gerasimos; Stiansen, Endre (21 April 1998). "Angelo Capato: A Greek Trader in the Sudan" (PDF). Sudan Studies – Official Newsletter of the SUDAN STUDIES SOCIETY OF THE UNITED KINGDOM: 10–18.

- ^ "Back Matter (advertisement)". Sudan Notes and Records. 34 (2). December 1953. JSTOR 41719486.

- ^ a b Babiker, Mahjoub Abd al-Malik (1985). Press and Politics in the Sudan. Khartoum: University of Khartoum. pp. 39–45, 56. ISBN 0863720528.

- ^ Tsakos, Alexandros (2009). Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette; Tsakos, Alexandros (eds.). The Agarik in Modern Sudan – A Narration Dedicated to Niania-Pa and Mahmoud Salih. Bergen: BRIC – Unifob Global & Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Bergen. pp. 115–129.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Obituary G.A.Contomichalos, O.B.E.". Great Britain and the East. London: Great Britain and the East, Ltd. 1954.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2013). 'D'irat al-Mahd : money, faith and politics in Sudan. Durham: University of Durham, Institute for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies.

- ^ Mills, David E. (2014). Dividing the Nile: Egypt's Economic Nationalists in the Sudan 1918–56. Cairo, New York: American University of Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774166389.

- ^ "Επιστολή του Τραπεζιού Αθηνών προς τον Ε.Βενιζέλο σχετικά με την κατάθεση 50000 δραχμών στο όνομα του". Venizelos Archives (in Greek). 18 October 1918. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Andrikopoulos, Giannēs (1987). Hē dēmokratia tou Mesopolemou, 1922–1936 (in Greek). Phytrakēs, Ho Typos.

- ^ Collins, Robert O. (1983). Shadows in the Grass: Britain in the Southern Sudan, 1918–1956. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 365–405.

- ^ Contomichalos, Catherine (28 January 2010). "Catherine Contomichalos (Haicalis)". Geni. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Iraq Chair in Arabic and Islamic Studies Marilyn (University of Edinburgh) Booth, ed. (2014). Long 1890s in Egypt: Colonial Quiescence, Subterranean Resistance. Edinburgh: University Press. pp. 272–273.

- ^ Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage. Vol. 1 (107th ed.). Wilmington, Delaware: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd. p. 790.

- ^ Niblock, Tim (1987). Class and Power in Sudan: The Dynamics of Sudanese Politics, 1898–1985. SUNY Press. p. 243.

- ^ Bricault, Giselle (1987). Major Transportation Companies of the Arab World 1987/88. Springer Buch. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-86010-737-8.

- ^ Annual Report 2015 (PDF). Khartoum: United Insurance. 2016. p. 8.

- ^ "ΣΥΝΕΔΡΙΑΖΕΙ ΤΗ ΔΕΥΤΕΡΑ ΤΟ ΔΗΜΟΤΙΚΟ ΣΥΜΒΟΥΛΙΟ". Anexartitos Blog (in Greek). 8 February 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- 1883 births

- 1954 deaths

- 20th century in Sudan

- 20th-century Greek people

- Anglo-Egyptian Sudan people

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Grand Commanders of the Order of George I

- Grand Commanders of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

- Greek diaspora in Africa

- Greek merchants

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Argostoli

- Greek expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Expatriates in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

- Greek expatriates