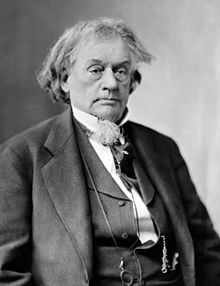

Garland H. White

Garland H. White | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1829 Hanover County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | July 5, 1894 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | abolitionist, minister, army chaplain, and politician |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Georgiana, Sallie |

Garland H. White (1829 – July 5, 1894) was a preacher and politician who served as Chaplain for the 28th United States Colored Infantry (28th USCT). He was one of the few black officers in the US Civil War. Before the war, he was owned by Congressman and future Confederate cabinet member and general, Robert Toombs. He escaped slavery to Ontario just before the war started and became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). He returned to the United States to preach and to recruit black soldiers. He joined the 28th USCT, which he helped recruit, and took part in the Battle of the Crater and the capture of Richmond. After the war, he moved to North Carolina where he continued preaching and was one of few black Democratic politicians.

Early life

[edit]Garland H. White was born in 1829 to a woman named Nancy in Hanover County, Virginia[1] just northwest of Richmond, Virginia. While Garland was still young, his owner sold him to Robert Toombs, who was a lawyer and, in 1844, became a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. It is not known when Toombs purchased White, but it has been estimated as being around 1839[2] or in 1845. White accompanied Toombs to Washington, D.C., while he was in the House. White had no education as a slave and may have gained basic reading and writing skills while working as a servant in Washington.[1] Another man owned by Toombs and a friend to White by the name of William Gaines also became a notable Methodist preacher, but was not freed until the Union Army arrived in Georgia during the Civil War.[3]

Escape from slavery

[edit]

In August 1850, White attempted to escape with another slave, assisted by William L. Chaplin.[4][5][6][a] slave named Allen and White were owned by then congressmen Alexander Hamilton Stephens[b] and Robert Toombs of Georgia, respectively.[4][5][c]

Both were caught when a posse of six slave catchers attacked Chaplin's carriage out of Washington. During the milieu, the posse shot into the carriage, wounding the runaway slaves, who were then returned to their slave holders. Chaplin was held in two jails for 19 weeks. He was bailed out, left the area, and did not return for the trial.[10]

In 1852, Toombs was elected to the U.S. Senate and White again accompanied Toombs to the capital. It was around this time with White met abolitionist William Seward, who was then a U.S. Senator and who lived two doors down from Toombs in the capital.[11] White studied for the ministry and received certification to preach the gospel on September 10, 1859.[12] He was granted license to preach at a gathering called the "4th Quarterly Conference", likely a local gathering of the AME, in Washington, Georgia.[1] Shortly later in 1859[1] or 1860, White escaped from Toombs in 1860 and fled to London, Ontario.[13] In Canada, he met and befriended future bishop of the Independent Methodist Episcopal Church (which would later unite with the AME church), Augustus Green.[14] In October 1861, he was appointed by Bishop Green to the charge of the London AME mission.[1]

Civil War

[edit]After the start of the American Civil War, he followed news about the war in the papers and wrote from Canada to then U.S. Secretary of State William Seward offering his services to the Union. In May 1862 he again offered his services, this time offering to form a black regiment in hopes that Union victory would lead to the "eternal overthrow of the institution of slavery."[13] In 1862, the U.S. Congress decided to cease enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and White returned to the US. In 1863 he became the pastor of a black Methodist congregation in Toledo, Ohio. When blacks were allowed to join the Union Army, he began to recruit blacks in Ohio, Indiana, New York, and Massachusetts.[15] White's recruitment first concentrated on the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry and he originally hoped to be appointed chaplain of one of these.[1] It has been claimed that White was the first black man accepted into Federal Service as a chaplain,[16] but the first black chaplain was appointed in mid-1863 to the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. As a recruiter, White would have been paid $15 per recruit.[1] He was asked to recruit in Indiana in 1863 by Governor Oliver Morton, who offered White a chaplaincy if he could recruit the state's quota of black soldiers.[17] From that point, he was particularly involved in the recruitment of the 28th USCT.[15] White once claimed that he "recruited colored men for every colored regiment raised in the north", and that he "canvassed the entire north and west urging my people to enlist."[18] However, he was noted for his self-promoting, and may have over-stated his contributions. More realistically, although probably also hyperbolic, he claimed that he recruited half the men in the 28th USCT raised in Indiana.[18] Fewer than three dozen blacks were commissioned as officers during the war, fourteen of these as chaplains. Thus, the majority of black regiments had white chaplains.[19]

Enlistment

[edit]He enlisted in the regiment as a private in Company D so that he could be promoted chaplain when recruitment was complete. The last four companies of the regiment did not fill quickly, however, and his official promotion was significantly delayed.[18] He served as acting chaplain but with a private's pay before promoted.[1] White claimed to be willing to serve as a private should his elevation to chaplain be denied, but his writing expressed a sense of superiority over other privates in the regiment,[19] and it is unlikely that he performed ordinary duties as a private, and was still active as a recruiter for that time.[1] While still a private, the regiment left Indianapolis on April 24, 1864, for Washington, D.C.[1] White continued to advocate for his promotion to the chaplaincy of the 28th USCT and wrote another letter to Seward about this time.[20]

On June 2, 1864, the regiment moved to White House Landing to be a part of MG Ambrose Burnside's Ninth Corps in MG George Meade's Army of the Potomac. The men worked as laborers until June 28 when they accompanied MG Philip Sheridan's cavalry to Prince George's Court House where it was assigned to the all-black 4th Division commanded by BG Edward Ferrero in the trenches before Petersburg. All this time, he continued to recruit for the regiment, mostly former slaves from Virginia and Maryland.[1] The first action the regiment saw was at the Battle of the Crater. In the battle, White likely was assigned to the surgeon or other support activities and his job as acting chaplain was to comfort the wounded and dying soldiers.[1] After the battle, about 400 men from Maryland were assigned to the regiment as well as a few from Indiana, and by late August the regiment was considered to be at full strength and regimental staff officers were authorized. On September 1, 1864, White was elected Chaplain by the officers of the regiment which was approved in October; he was discharged as a private and mustered in as a chaplain effective October 25 with the pay of a captain.[1] While in the lines before Petersburg, White complained of a respiratory illness, and he had a chronic cough for the rest of his life.[1]

In late October, the regiment moved to Poplar Grove Church, west of Petersburg. On November 18, it was ordered out of the line of the siege and to travel to the Bermuda Hundred on the James River and assigned to provost duty at the army's supply depot at City Point. In December, it was assigned to a corps led by MG Godfrey Weitzel.[1] Lee retreated from Richmond on April 2, 1865, and Union forces entered on April 4; the 28th USCI was among the first regiments to enter the city and White walked at the head of the column. Later that day White witnessed the arrival of Abraham Lincoln and the celebration among people of Richmond at their "Great Emancipator".[21] In Richmond, White gave a speech on Broad Street. Many liberated black people in the city searched among the black troops for relatives, and his prominence drew notice from the crowd and he was reunited with his mother, an event which was emotionally recounted in a letter to The Christian Recorder.[1]

| Reunion of Garland H. White and his mother, Nancy "What is your name, sir?" A letter from Chaplain Garland White, Indiana's first African American officer |

After three days in Richmond, the 28th returned to City Point and did not accompany the army to Appomattox Court House where Lee surrendered. After Lee surrendered, the regiment was assigned to guard prisoners of war processed through City Point and guard the prison camp at Point Lookout in St. Mary's County, Maryland. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, at which point most white soldiers were discharged as they were enlisted "for three years or the duration" and had volunteered more than three years before. Black soldiers, who were not allowed to enlist until later in the war became responsible for occupying the South.[22] While at City Point, White provided religious counselling to private Samuel Mapp of Company D, 10th USCT, who was sentenced to die by the army. White was the only chaplain at City Point, and thus overwhelmed by duties.[1]

Newspaper correspondence

[edit]White was a frequent writer of letters, both private and for newspaper publication. His voice in his letters varied and matured as he wrote. He sometimes wrote with great assertiveness and other times great deference. This tension has been compared to the tension between the styles of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.[23] White wrote frequently to the paper, the Christian Recorder. In his letters, he wrote about many issues regarding black liberation and black military service. Combining themes, he argued that blacks should liberate themselves through joining the Union Army.[16] He advocated for the enlistment of black units by state rather than mixing them together.[24] Controversially, White wrote that blacks in the Union Army should not concern themselves greatly with equal pay and instead focus on victory and personal improvement.[25] He also wrote about many details of his regiment's experience, including an emotional description of the Battle of the Crater and of the Fall of Richmond, as well as their time in Texas after the war.[26] White believed there was a difference between blacks who were free before the war and those who were emancipated during the war. For instance, in a letter published in the Christian Recorder after the Battle of the Crater, he praised the performance of the black troops raised in free states when compared to those raised in slave states. White felt that education and reduction of illiteracy in these troops would greatly improve them.[27]

In late May, the regiment sailed to Texas, arriving in Indianola on July 4 and moving to Corpus Christi on August 13 as a part of General Russell's brigade. The regiment faced casualties from disease in the trip, but saw less illness once in Texas than they had in Virginia, although 17 died of disease in September 1865, in part due to poor conditions in the hospitals.[1] From Texas, White continued to contribute letters to the Christian Recorder, where he discussed black suffrage.[22] At demobilization on November 8, 1865, White gave every Christian "in this Command" a certificate of good moral and religious standing.[1] After mustering out, the regiment sailed to New Orleans and then took a riverboat to Cairo, Illinois, and finally a train to Indianapolis. They arrived in Indianapolis on January 6, 1866.[1]

After the war

[edit]

White married a woman named Georgiana, probably in 1861. They had their first child, Anna, in 1862 while living in Canada. After the war, they had two more children, Jane in 1867 and Henry in 1869. After the war, White tried and failed to gain an appointment with the Freedmen's Bureau, and returned for a short time to Indiana and Ohio before moving to North Carolina.[28] Georgiana died probably about the time White moved to North Carolina in 1872. Some time after Georgiana died, White remarried a woman named Sallie. Sallie was born in about 1860.[1] In 1874, White ran for Congress in North Carolina's Black Second District as an independent candidate against Republican John Adams Hyman, but finished a distant third behind Hayman and Democrat George W. Blount; local Republicans alleged his candidacy was promoted by the Democratic party to divide the Black vote.[28][29] In 1876, White campaigned in support of Democrat Samuel J. Tilden for president against the eventual winner, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes.[30] Around this time, White was a pastor at a church in Halifax, North Carolina, but he was dismissed by his congregation for his support of the Democrats before the end of the 1870s.[14] When the Federal government withdrew from North Carolina in 1877, White's position as a supporter of the Democrats put him on the side of the party which would soon come to power in the state. At the same time, this put him at odds with most Blacks in the area.[30]

In 1882, White's health forced him to move to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he hoped to find relief. However, his health worsened and he moved back to the northern part of the state, settling in 1884 in Weldon, North Carolina, near to his former home in Halifax. He was bedridden for much of the time after September 1884, and in July 1885 applied to Washington for an invalid pension based on a respiratory illness contracted during the siege of Petersburg. His application took almost five years to process as he had not been hospitalized during active service. He moved to Washington, D.C., possibly to be closer to his attorney, in the spring of 1889. In June 1890, invalid pension laws for former soldiers no longer required the soldier's disability be due to injury or illness contracted on active duty and in early July, White was awarded a pension backdated to July 7, 1885. While in the capital, he worked as a messenger.[1] His illness continued and he died July 5, 1894, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ After later escaping, Garland was the chaplain of the 28th United States Colored Infantry Regiment during the Civil War.[7] The marker for the incident erroneously states that it was Allen who was the chaplain.[5][7] Prince and others state that the two fugitives were Allen and Garland.[4][5] Scoggins states that the escapees were Louisa and Garland.[8]

- ^ Stephens was later vice president of the Confederate States of America.[4]

- ^ The Liberator states that the events took place in August 1849, but says Chaplin was under arrest in October 1850.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Miller 1997

- ^ Levine 2013, p16

- ^ Levine 2013, p238

- ^ a b c d Prince, Bryan (2010). "Chapter 3". A Shadow on the Household: One Enslaved Family's Incredible Struggle for Freedom. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-7126-3.

- ^ a b c d "William L. Chaplin Arrested! Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Miller Jr., Edward A. (1997). "Garland H. White, black army chaplain". Civil War History. 43 (3): 201–218. doi:10.1353/cwh.1997.0092. S2CID 145659016.

- ^ a b "Indiana's 28th Regiment: Black Soldiers for the Union" (PDF). Indiana State Government. p. 6. Retrieved 2021-03-24.

- ^ Scroggins, Mark (19 Jul 2011), Robert Toombs: The Civil Wars of a United States Senator and Confederate General, McFarland, pp. 66–67

- ^ "Slavery Diabolical". The Liberator. April 25, 1851. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Green, Samuel Abbott (1914). Facts Relating to the History of Groton, Massachusetts. J. Wilson and Son. pp. 87–88.

- ^ Hagar 2013, p188

- ^ Scroggins 2011, p160

- ^ a b Levine 2013, p131

- ^ a b Prince 2015, p288

- ^ a b Levine 2013, p161

- ^ a b Harbour 2008, p244

- ^ Harbour 2008, p246

- ^ a b c Reid 2014, p104

- ^ a b Hagar 2013, p199

- ^ Scroggins 2011, p160-161

- ^ Hagar 2013, p184

- ^ a b Hagar 2013, p212-215

- ^ Hagar 2013, p191

- ^ Harbour 2008, p248

- ^ Harbour 2008, p244-245

- ^ Madison 2014, p99

- ^ Hagar 2013, p202

- ^ a b Hagar 2013, p216-217

- ^ Anderson, Eric (1981). Race and Politics in North Carolina, 1872–1901: The Black Second. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University. p. 44.

- ^ a b Hagar 2013, p217

- ^ "Garland H White, died July 5, 1894, plot Section 27 Site 629-A", Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, U.S. Veterans' Gravesites, National Cemetery Administration

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, Eric. Race and Politics in North Carolina, 1872–1901: The Black Second. Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

- Hager, Christopher. Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing. Harvard University Press, 14 Feb 2013

- Harbour, Jennifer Rebecca. "Bury Me in a Free Land": African-American Political Culture and the Settlement Movement in the Antebellum and Wartime Midwest. Dissertations & Theses-Gradworks. University of Iowa, 2008

- Levine, Bruce. The Fall of the House of Dixie: The Civil War and the Social Revolution That Transformed the South. Random House Publishing Group, 8 Jan 2013

- Madison, James H., Sandweiss, Lee Ann. Hoosiers and the American Story. Indiana Historical Society, 1 Oct 2014.

- Miller Jr, Edward A. "Garland H. White, black army chaplain." Civil War History 43.3 (1997): 201–218.

- Prince, Bryan. My Brother's Keeper: African Canadians and the American Civil War. Dundurn, 10 Jan 2015

- Reid, Richard M. African Canadians in Union Blue: Volunteering for the Cause in the Civil War. UBC Press, 13 May 2014

- Scroggins, Mark. Robert Toombs: The Civil Wars of a United States Senator and Confederate General. McFarland, 19 Jul 2011

- White, Garland H. Letter to the Christian Recorder dated April 12, 1865. Published in the Christian Recorder, April 22, 1865, Accessed April 26, 2016, at http://www.in.ng.mil/Portals/0/PageContents/AboutUs/History/A%20letter%20from%20Chaplain%20Garland%20White.pdf

- 1829 births

- 1894 deaths

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American abolitionists

- African-American Methodists

- Underground Railroad people

- People from Hanover County, Virginia

- Politicians from Toledo, Ohio

- People from Indiana

- People from Halifax, North Carolina

- Politicians from Wilmington, North Carolina

- People from Weldon, North Carolina

- People of Indiana in the American Civil War

- African Americans in the American Civil War

- North Carolina Democrats

- People of the African Methodist Episcopal church

- United States Army chaplains

- African Methodist Episcopal Church clergy

- Methodist abolitionists

- 19th-century American slaves

- 19th-century American clergy