Colombian–Peruvian territorial dispute

| Colombian–Peruvian Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the South American territorial disputes | |||||||

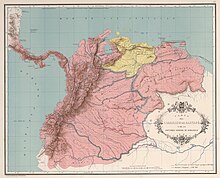

Map of the disputed territories in the 20th century | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Colombian–Peruvian territorial dispute was a territorial dispute between Colombia and Peru, which, until 1916, also included Ecuador.[Note 1] The dispute had its origins on each country's interpretation of what Real Cedulas Spain used to precisely define its possessions in the Americas. After independence, all of Spain's former territories signed and agreed to proclaim their limits in the basis of the principle of uti possidetis juris, which regarded the Spanish borders of 1810 as the borders of the new republics. However, conflicting claims and disagreements between the newly formed countries eventually escalated to the point of armed conflicts on several occasions.

The dispute between both states ended in the aftermath of the Colombia–Peru War, which led to the signing of the Rio Protocol two years later, finally establishing a border agreed upon by both parties to the conflict.

Spanish era

[edit]

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Spanish Empire's possessions in the Americas were initially divided into two viceroyalties: the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru. From these viceroyalties, new divisions would be later established to better administer the large territories in Central America, South America and the Caribbean.

On May 27, 1717, the Viceroyalty of New Granada was established on the basis of the New Kingdom of Granada, the Captaincy General of Venezuela and the Royal Audience of Quito.[1] It would be temporarily dissolved on November 5, 1723, and its territories reincorporated into the Viceroyalty of Peru,[2] but in 1739 it was re-established again and definitively, with the same territories and rights that it had according to the Royal Decree of 1717.[3]

A series of royal decrees followed in the following century until 1819.[4][5] The decree of 1802 would later serve as the basis of the conflict between Ecuador and Peru, with its existence being disputed by the former. The decree of 1740 has also been called into question by the latter, with some historians also questioning its existence.[6][7]

After the wars of independence, the new republics in South America agreed to proclaim their limits in the basis of the principle of uti possidetis juris, which regarded the Spanish borders of 1810 as the borders of the new states.[8]

Wars of Independence

[edit]

The formal independence of Guayaquil was declared on October 9, 1820, establishing the Free Province of Guayaquil and beginning the proclaimed state's independence campaign.[9] Public opinion was divided into three: one part supported annexation to the Protectorate of Peru, another annexation to the Republic of Colombia, and another supported independence.[10]

Around the same time, a newly independent Republic of Colombia established three provinces in October 1821: the northern, central, and southern provinces. The latter nominally included the Jaén de Bracamoros Province.[11] The province, however, had declared itself part of the Presidency of Trujillo on June 4, alongside Tumbes on January 7 and Maynas on August 19.[12][13] With the entry of San Martín's troops into Lima on June 9, the Peruvian proclamation of independence took place on July 28 of the same year, and Trujillo, Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas being integrated into the new state.[14][15]

On July 22, 1822, Antonio José de Sucre ordered Jaén to swear to the Colombian constitution and thus, to form part of Colombia. The city rejected the mandate, arguing that it had deputies in the Peruvian Congress. Simón Bolívar himself made Sucre desist from his plans for the same reasons.[16]

Gran Colombia–Peru conflict

[edit]

The Guayaquil issue was approached with care by both countries, who signed a treaty on July 6, 1822, allowing special privileges to citizens of both states.[17] The issue, yet to be resolved, was postponed.[18]

On September 1, 1823, Simón Bolívar arrived in Callao, aboard the brig Chimborazo, invited by the Peruvian Congress to "consolidate the independence" of Peru. On December 18 of the same year, the Galdeano-Mosquera Agreement was signed in Lima, which established that "Both parties recognize the limits of their respective territories, the same ones that the former Viceroyalties of Peru and Nueva Grenada." It was approved by the Peruvian Congress, but months later the Colombian Congress disregarded the agreement.[19]

On December 9, 1824, the Battle of Ayacucho took place, ending the war in Peru. After the fact, protests against Bolívar, who remained Dictator of Peru, took place. During his government, the territorial question was not brought up, and governors in Jaén and Maynas were appointed, apparently recognizing Peru's ownership of the territories.[20][21][22] In correspondence with Francisco de Paula Santander on August 3, 1822, Bolívar recognized that both Jaén and Maynas legitimately belonged to Peru.[23]

With Bolívar withdrawing in 1826, liberal and nationalist elements in Peru put an end to the Bolivarian regime in January 1827. The new government dismissed the Colombian troops and expelled the Colombian diplomatic agent, Cristóbal Armero.[24] Throughout the country, several protests were organized against Bolívar and Sucre.[25] At the same time, the Peruvian army under the command of Agustín Gamarra entered Bolivia and forced Sucre to resign from the presidency, ending Colombian influence in that country.

To remedy the crisis, Peru sent José Villa to Colombia as minister plenipotentiary. Bolívar refused to receive him and, through the Colombian foreign minister, asked Peru for explanations about the dismissal of Colombian troops, the intervention in Bolivia, the expulsion of Armero, the debt of independence and the restitution of Jaén and Maynas.[26] Next, Villa received his passports.[27]

The situation between Colombia and Peru worsened as time went by. On May 17, 1828, the Peruvian Congress authorized President José de la Mar to take military measures as a response to Villa's expulsion. On July 3, 1828, however, the Republic of Colombia officially declared war on the Peruvian Republic, beginning the Gran Colombia–Peru War.[28]

The Peruvian Navy blockaded the Colombian coast and besieged the port of Guayaquil, occupying it on January 19, 1829. The Peruvian Army occupied Loja and Azuay. Despite the initial success of the Peruvian Army, however, the war ended with the Battle of Tarqui, on February 27, 1829; and with the signing of the Girón Agreement the following day.

The Agreement was disapproved by Peru due to Colombian actions considered offensive. Therefore, La Mar was willing to continue the war, but was overthrown by Agustín Gamarra. The latter, wishing to end the conflict, signed the Piura Armistice that stipulated the suspension of hostilities and the return of Guayaquil. To put a definitive end to the dispute, the representatives of Peru and Colombia, José Larrea and Pedro Gual respectively, met in Guayaquil, and on September 22, 1829, the Larrea-Gual Treaty was signed, which constituted a treaty of peace and friendship, but not limits. Its articles 5 and 6 established the basis that should serve for the delimitation between the two countries and the procedure that would be used for it.[29] As for the procedure to carry out said delimitation, it ordered that a Commission of two people for each republic should be appointed to go over, rectify and fix the dividing line, work that should begin 40 days after the treaty had been ratified by both countries. The tracing of the line would start at the Tumbes River. In case of disagreement, it would be submitted to arbitration by a friendly government.[30][31] The delimitation mission did not take place, however, as problems took place, such as both parties arrived at different times, and the dissolution of Gran Colombia itself into New Granada, Ecuador[32] and Venezuela,[33][34] which further complicated the issue.[35][36]

Conflict with Brazil and Ecuador

[edit]With Gran Colombia dissolved, the conflict now included the newly formed Republic of Ecuador and the Empire of Brazil.

Creation of Popayán Province

[edit]After the separation, Nueva Granada was constituted territorially according to the division of 1810.[37] Thus, Popayán Province was created, which established the Napo River and its confluence with the Amazon as its southern limit.

Ecuadorian–Colombian War

[edit]On February 7, 1832, due to territorial disputes over the provinces of Pasto, Popayán and Buenaventura, the republics of New Granada and Ecuador went to war. The conflict was favorable for the former and ended with the Treaty of Pasto, which only delimited the first section of the border between the two nations: the Carchi River.

Pando–Noboa Treaty

[edit]| Treaty of Friendship and Alliance Between Peru and Ecuador | |

|---|---|

| Type | Friendship treaty |

| Signed | 12 July 1832 |

| Location | Lima |

| Signatories | |

| Full text | |

Peru recognized Ecuador as an independent nation, and received its representative in Lima, Diego Noboa. On July 12, 1832, two agreements were concluded: one of friendship and alliance, and another of trade.[38] They were approved by the Congresses of both countries, and the respective ratifications were exchanged.[39]

The treaty is important because it recognized the existing limits, that is, the possessory state of Peru of Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas (against the interests of Granada) and, that of Ecuador, of Quito, Azuay and Guayaquil; until the signing of a definitive boundary treaty.

The Granadine minister in Lima, José del C. Triunfo, considered that the treaty violated the rights of his country, and raised a protest against it.[40]

Creation of Amazonas Department

[edit]On November 21, 1832, the Peruvian Congress created the Department of Amazonas, made up of the provinces of Chachapoyas, Pataz and Maynas; separating from the Department of La Libertad.[41]

Juan José Flores and Peru

[edit]Juan José Flores assumed the government of Ecuador again in 1839. His foreign policy corresponded to his desire to expand the Ecuadorian territory to the detriment of New Granada and Peru. His expansionist spirits increased when, after the dissolution of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, numerous political voices from the ephemeral state revived the Bolivarian claim of Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas.[42]

Then, two negotiations took place between both countries: between the Peruvian ministers Matías León and Agustín Guillermo Charún, and the Ecuadorians José Félix Valdivieso and Bernardo Daste, which failed. However, its importance lies in the fact that for the first time Peru based its rights over Maynas invoking the Royal Decree of 1802 (then lost) and the self-determination of peoples, as it would also do in future negotiations with Colombia.[43]

Real Cédula of 1802 published

[edit]On March 3, 1842, the recently founded newspaper El Comercio published for the first time the text of the Real Cédula of 1802, whose existence had been questioned and doubted. About the original, the same newspaper indicated that there was a copy in the High Court of Accounts and another in the archive of the convent of Ocopa, transferred to Lima. The official files were lost during a fire.[44]

Referendum in Maynas Province

[edit]In May 1842, acts were signed in the province of Maynas, which ratified the will of its inhabitants to belong to Peru.[44]

Creation of Caquetá Territory

[edit]On May 2, 1845, the Caquetá Territory was separated from Popayán Province. The city of Mocoa was designated as the capital, covering the territories bathed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, Napo and Amazon rivers, from the border with Ecuador to Brazil.

1851 Treaty between Peru and Brazil

[edit]| Fluvial Convention on Commerce and Navigation between the Republic of Peru and the Empire of Brazil | |

|---|---|

| Type | Border treaty |

| Signed | 23 October 1851 |

| Location | Lima |

| Signatories | |

| Full text | |

On October 23, 1851, a fluvial convention was signed by Bartolomé Herrera (for Peru) and Duarte Da Ponte Ribeyro (for Brazil). In its eight article, the first section of the border of both countries was delimited: the Apaporis-Tabatinga line and the Yavarí River.[45]

To prevent doubts regarding the mentioned Border, in the stipulations of this Convention; the high contracting parties accept the uti possidetis principle according to which the limits between the Republic of Peru and the Empire of Brazil will be fixed; Therefore, they recognize, respectively, as the border of the town of Tabatinga, and from Tabatinga to the North the straight line that will meet in front of the Yapurá River at its confluence with the Apaporis, and from Tabatinga to the South the Yavary River, from its confluence with the Amazon.

When the Granadine government was made aware of this agreement, it ordered its minister in Chile, Manuel Ancízar, to raise a protest in April 1853; stating that it violated the Treaty of San Ildefonso of 1777.[46]

Creation of the Political and Military Government of Loreto

[edit]On March 10, 1853, the Peruvian government created the Political and Military Government of Loreto, assigning the city of Moyobamba as its capital. It covered the territories and missions located to the north and south of the Amazon and its respective tributaries, in accordance with the Royal Decree of 1802.[47]

Given this fact, the Plenipotentiary Minister of New Granada in Lima, Mariano Arosemena, and that of Ecuador, Pedro Moncayo, raised a protest. José Manuel Tirado, then Foreign Minister of Peru, maintained that, according to the uti possidetis iure of 1810, those territories belonged to his country. He based himself on the Royal Decree of 1802 and the self-determination of peoples.[48][49]

1853 Ecuadorian Law

[edit]On November 26, 1853, the Ecuadorian Congress enacted a law, declaring "free navigation of the Chinchipe, Santiago, Morona, Pastaza, Tigre, Curaray, Nancana, Napo, Putumayo and other Ecuadorian rivers that descend to the Amazon." The Peruvian Minister Plenipotentiary in Quito, Mariano José Sanz León, forwarded his protest.[50]

1856 Treaty of Bogotá

[edit]| Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between New Granada and Ecuador | |

|---|---|

| Type | Friendship and border treaty |

| Signed | 9 July 1856 |

| Signatories | |

On July 9, 1856, the plenipotentiary minister of New Granada, Lino de Pombo; and that of Ecuador, Teodoro Gómez de la Torre, signed a treaty, in which the provisional limits between both nations were recognized as those defined by the Colombian law of July 25, 1824, annulling what was decreed by the Treaty of Pasto.[51]

Creation of the Federal State of Cauca

[edit]On June 15, 1857, within the Granadina Confederation, the Federal State of Cauca was created.[52] The city of Popayán was designated as its capital and its limits to the south extended from the mouth of the Mataje River to the mouth of the Yavarí River in the Amazon.

Arbitration of Chile between New Granada and Ecuador

[edit]In 1858, the governments of New Granada and Ecuador decided to go to arbitration in Chile, to resolve conflicts in the Amazon region. The arguments were presented by Florentino González, on behalf of Nueva Granada; and Vicente Piedrahíta, for Ecuador. However, the Chilean government did not issue a ruling, due to the vagueness of its powers and the lack of a formal commitment.[53]

Ecuadorian–Peruvian War

[edit]

On October 26, 1858, the war between Peru and Ecuador began, because, according to the Peruvian plenipotentiary Juan Celestino Cavero, the Ecuadorian government decided to settle its foreign debt with England by ceding Peruvian Amazonian territories. After a successful blockade campaign of the Ecuadorian coast and the occupation of Guayaquil, the Franco-Castile Treaty, also called the Treaty of Mapasingue, was signed. In this document, the validity of the Royal Decree of 1802 and the uti possidetis of 1810 were recognized:

Article VI. The governments of Ecuador and Peru will rectify the limits of their respective territories, appointing within a term of two years, counted from the ratification and exchange of this treaty, a mixed commission that, in accordance with the observations that it makes and the vouchers that are presented by both parties, indicate the limits of the two republics. Meanwhile, they accept as such limits those that emanate from the uti possidetis, recognized in article 5 of the treaty of September 22, 1829 between Colombia and Peru, and that of the former Viceroyalties of Peru and Santa Fe, according to the Royal Decree of July 15, 1802.

The Boundary Commission between Brazil and Peru

[edit]In accordance with the 1851 treaty between Peru and Brazil, both governments appointed their respective commissioners in 1866 to place the respective milestones from the mouth of the Apaporis, continuing through the Putumayo (where there were some exchanges of territories) and exploring the Yavarí River, determining (incorrectly) its origin at coordinates 07°01′17″S 74°08′27″W / 7.02139°S 74.14083°W, when in fact it is at coordinates 07°06′51″S 73°48′04″W / 7.11417°S 73.80111°W.[54]

Direct negotiations

[edit]

First Spanish arbitration

[edit]In 1887, the Ecuadorian government tried to renew the cession of territories to an English company. Peruvian Foreign Minister Cesáreo Chacaltana raised his protest and his government proposed taking the border problem to arbitration in Spain. Through the Espinoza-Bonifaz Arbitration Agreement, both parties agreed to submit the border problem to arbitration by the King of Spain.[55] Both countries presented their arguments in 1889: Peru, through its commissioner José Pardo y Barreda; however, the Ecuadorian document was lost, so a copy had to be sent.

García–Herrera Treaty

[edit] Black: borders as per the treaty Yellow: Peruvian modifications Red: current border | |

| Type | Border treaty |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 1890 |

| Signed | 2 May 1890 |

| Location | Guayaquil |

| Signatories | |

The García-Herrera Treaty was a border treaty between Ecuador and Peru signed in 1890 but never effective.

The Foreign Minister of Ecuador, Carlos R. Tobar, proposed to his Peruvian counterpart, Isaac Alzamora, to enter into direct negotiations to definitively resolve the boundary dispute, dispensing with Spanish arbitration. Alzamora, in turn, accepted, and sent Arturo García as representative, initiating discussions with his Ecuadorian counterpart Pablo Herrera González.

In order to counter popular opinion, the Peruvian government of Andrés Avelino Cáceres at first stressed the importance of such a treaty, due to a plebiscite regarding Tacna and Arica, territories occupied by Chile since the War of the Pacific.[56]

Disagreements soon appeared, as the Peruvian government presented revisions to the treaty, which Ecuador refused to accept. At the same time, Peru refused to accept the original proposal. As a result of these disagreements, the treaty was never applied.[57]

In 1890 and 1891, the Colombian government raised its protest in both Quito and Lima, since this treaty interfered with its claims in the Napo and Amazon rivers.[58][59]

1890 Colombian Law

[edit]On December 22, 1890, the Colombian Congress issued a law by which authorizations were given to create missions and police services in the regions bathed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, Amazonas rivers and their tributaries.

Peruvian Foreign Minister Alberto Elmore raised his protest on April 8, 1891, considering that the law violated the territorial rights of Peru, in accordance with the Royal Decree of 1802 and the possession of his country, since the inhabitants of those places obeyed the laws, the regulations and the Peruvian authorities of the Department of Loreto. His Colombian peer, Marco Fidel Suárez, indicated that:[60]

(...) consulting harmony and in order not to undermine interests already created, it will not extend its action except to the territories that are currently lacking in missions and colonization (...) that such respect is not interpreted as the recognition of true domain titles and territorial sovereignty.

1894 Tripartite Conferences

[edit]

The Colombian government, on the occasion of the diplomatic efforts between Ecuador and Peru, requested to be admitted to the boundary discussions in order to reach a definitive agreement; such efforts culminated with the tripartite convention meeting in Lima on October 11, 1894. Aníbal Galindo, as special lawyer, and Luis Tanco, who was chargé d'affaires in Lima, were appointed as representatives for Colombia; for Ecuador, Julio Castro, extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador in Lima; and for Peru, Luis Felipe Villarán, as special counsel.[61][62]

Upon entering the dispute, Colombia upheld the recognition of the uti possidetis, but integrating and replacing it (in cases of obscurity and deficiency) with the principle of equity and reciprocal convenience. According to his thesis, the arbitrator should not only attend to the titles of law, but also the interests of the countries in dispute.

Colombia defined its position on the General Command of Maynas, which was disputed by the three countries. Peru maintained that, according to the uti possidetis, the territory belonged to Peru, as mandated by the Royal Decree of 1802; while Ecuador had maintained its non-existence and, when the certificate was presented, its non-compliance. For its part, Colombia disputed the legal nature of the document, and argued that it was not a political or civil demarcation, but an ecclesiastical order. Thus, the intention of the royal act was to place the ecclesiastical missions in Maynas under the supervision of the Viceroyalty of Peru, but depending politically on that of New Granada.

Regarding the possible rights of Ecuador, Colombia argued that these do not start from the certificate of erection of the Audiencia de Quito, since this was never an autonomous entity, but dependent on the viceroyalties of Peru and New Granada. Due to this, the uti possidetis cannot be claimed in its favor, which is only valid for territorial divisions such as the viceroyalties and the general captaincies. The Ecuadorian nation and its rights were born on February 10, 1832, when Colombia recognized the separation of the provinces of Ecuador, Azuay and Guayaquil, to form an independent state.[63]

The arbitration agreement was signed on December 15, 1894, since the three countries did not reach an agreement on their arguments. The first article said:[64]

Colombia adheres to the arbitration convention, signed between Peru and Ecuador on August 1, 1887, whose approval was exchanged in Lima on April 11, 1888; but the three high contracting parties stipulate that the royal arbitrator will rule on the issues that are the subject of the dispute, taking into account not only the titles and arguments of law that have been presented and that are presented, but also to the convenience of the contracting parties, reconciling them so that the border line is founded on law and equity.

The congresses of Colombia and Peru approved the agreement, but not Ecuador, who refrained from doing so. Colombia, for its part, and given Ecuador's conduct, preferred to engage in direct negotiations.[65] Peru withdrew its approval on January 29, 1904.[62]

Abadía Méndez-Herboso Protocol

[edit]On September 27, 1901, a protocol was signed between Colombian Foreign Minister Miguel Abadía Méndez and the Chilean plenipotentiary in Bogotá, Francisco J. Herboso, establishing an alliance between Chile, Colombia and (presumably) Ecuador.[66] The Colombian-Chilean negotiations continued, which included the sale of an armored vehicle of the Chilean Navy, which was, at that time, one of the most powerful in America and the world. This was frustrated, however, by the discovery and publication of these documents by the Peruvian plenipotentiary in Colombia, Alberto Ulloa Cisneros.

Rubber boom, later treaties, and the modus vivendi

[edit]Pardo-Tanco Argáez Treaty

[edit]On May 6, 1904, a treaty was signed in Lima between the Peruvian Foreign Minister José Pardo y Barreda and the Colombian Plenipotentiary Luis Tanco Argáez, which submitted the question of limits to the arbitration of the King of Spain. That same day, a modus vivendi was signed in the Napo and Putumayo areas.[67] However, it was not approved by Colombian Foreign Minister Francisco de Paula Matéus, arguing that Tanco had no instructions.[68][69]

Tobar–Río Branco Treaty

[edit]| Type | Border treaty |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 1904 |

| Signed | 4 May 1904 |

| Location | Rio de Janeiro |

| Effective | 1905 |

| Signatories | |

| Full text | |

The Tobar–Río Branco Treaty was signed between Brazil and Ecuador on May 4, 1904, the same day as the signing of the modus vivendi between Colombia and Peru. The governments of Ecuador (represented by Carlos R. Tobar) and Brazil (represented by José Paranhos) signed a treaty, in which they defined their border in the Apaporis-Tabatinga Line. According to a 1851 treaty, the border was originally defined as being between Peru and Brazil.

The Republic of Ecuador and the Republic of the United States of Brazil agree that, ending favorably for Ecuador, as this Republic expects, the dispute over boundaries between Ecuador and Peru, the border between Ecuador and Brazil, in the part that they border, is the same indicated by Art. VII of the Convention that was celebrated between Brazil and Peru, in Lima, on October 23, 1851, with the constant modification in the Agreement also signed in Lima on February 11 of 1874, for the exchange of territories in the Iza or Putumayo line, that is, that the border - in whole or in part - according to the result of the aforementioned litigation, be the geodesic line that goes from the mouth of the San Antonio stream, in the left bank of the Amazon, between Tabatinga and Leticia, and ends at the confluence of the Apaporis with the Yapurá or Caquetá, except in the section of the Iza or Putumayo river, cut by the same line where the alveo of the river, between the points of intersection, will form the division.

Velarde-Calderón-Tanco Treaties

[edit]

On September 12, 1905, the new Peruvian legation in Bogotá (directed by the Peruvian plenipotentiary Hernán Velarde) managed to celebrate three new conventions with the Colombian Foreign Ministry: the Velarde-Calderón-Tanco treaties, with Clímaco Calderón, Foreign Minister of Colombia; and the Colombian Minister Plenipotentiary in Peru, Luis Tanco Argáez.

The first agreement was a general arbitration agreement, by which both countries undertook to resolve all their differences, except those that affected national independence or honor, through arbitration. The referee would be the Pope. The arbitration commitment would last 10 years, with the contentious issues presented to the arbitrator by special conventions.

The second agreement submitted the question of limits to Pius X, or in his refusal or impediment, to the President of the Argentine Republic; establishing the principles of law and equity. The arbitration should only be initiated when the litigation between Peru and Ecuador, pending before the King of Spain, is over.

The third treaty was the status quo and modus vivendi in the disputed area. Neither of the two countries would alter their positions until the dispute was resolved. Meanwhile, the dividing line would be the Putumayo River, which would be neutral. Colombia would occupy the left margin and Peru, the right margin. Customs would be mixed and the product of these common.[70][71][65]

The agreements were approved by the Colombian Congress and sent for ratification in Lima. However, it seems that due to the enormous influence of the powerful Casa Arana, its approval was delayed.[72]

In this context, on June 6, 1906, a status quo protocol was signed in Lima in the disputed area and a modus vivendi in the Putumayo, a river declared neutral. Garrisons, customs, and civil and military authorities were withdrawn until the border conflicts were resolved.[73][74] These measures would indirectly barbarize the region.[75][76]

The rubber boom and the Putumayo genocide

[edit]Rubber exploitation had radically changed the lives of the inhabitants of the Amazon. Iquitos, Manaus and Belém received a great economic boost at that time. On the Peruvian side, Casa Arana was the owner of all the rubber territories from the Amazon to the current Colombian territory. His enormous commercial successes pushed him to create a company called the Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company, incorporated on September 27, 1907, with a capital of one million pounds sterling. The board was made up of Henry M. Read, Sir John Lister Kaye, John Russel Gubbins, Baron de Souza Deiro, M. Henri Bonduel, Abel Alarco, and Julio Cesar Arana.[77]

On August 9, 1907, Benjamín Saldaña Roca filed a criminal complaint in Iquitos against the employees of Arana's company. The accusation pointed out that horrible crimes were being committed against the indigenous people of Putumayo: rapes, torture, mutilations and murders. In Lima, the news was published by the newspaper La Prensa on December 30, 1907.[77] However, under the pretext that, due to the modus vivendi agreed upon the previous year, the Peruvian authorities did not have authority over the area between the Putumayo and Caquetá, the complaint was filed.[78]

In 1909, American citizens Hardenburg and Perkins were imprisoned by the Casa Arana because, according to them, they were reproached for the exploitation of indigenous people and workers in general. According to the company, Hardenburg had tried to blackmail them, indicating "that he had in his possession very compromising documents for the Peruvian Amazon Co."[79]

The following year, the world press was agitated by the so-called Putumayo scandals, thanks to Hardenburg's denunciation, who indicated the chilling figure of 40,000 murdered natives. The brutal crimes against the indigenous people, committed in that area by both Peruvians and Colombians, shook public opinion in Great Britain; even more so, when it was discovered that the accused for the terrible abuses had British capital.[80] Sir Roger Casement, the British consul in Manaus, was sent to investigate these events. Casement was already world famous, due to his denunciation of the abuse and mistreatment to which the native population in the Belgian Congo was subjected.[81]

The Supreme Court of Peru appointed, thanks to a complaint from the Attorney General of the Nation on August 8, 1910, a commission to investigate what happened in those territories. Carlos A. Valcárcel received the orders in November of that year, and on the 22nd, ordered that the alleged culprits be prosecuted. However, due to health problems and lack of money, Valcárcel was unable to take charge of the investigation, so he was replaced by Rómulo Paredes.[82]

Casement's report was presented at the beginning of 1911. In it, the horrible practices of the Arana house were described. The recruitment of natives at the hands of Peruvians and Colombians, slavery, sexual exploitation of women, the death of thousands of Amazonian indigenous people; which confirmed the allegations made earlier. Despite this, Julio César Arana would never be tried for his alleged crimes, neither before the House of Commons of Great Britain, nor before the Peruvian justice system. He would become a senator from Loreto and an opponent of the Salomón-Lozano Treaty.[81]

Putumayo–Caquetá armed incidents

[edit]Despite the agreements signed with Peru, on June 5, 1907, the Colombian government secretly held a convention with Ecuador, to negotiate a border agreement in the territories that were also in dispute with Peru. At the same time, it demanded that this country approve the 1905 treaty (which did not happen).[83]

Given this, on October 22, 1907, the Colombian government unilaterally declared the modus vivendi of 1906 ended, appointing and sustaining authorities in Putumayo. Because of this, the Peruvian Foreign Ministry asked Julio C. Arana to help with his employees to repel a possible Colombian invasion. As a consequence of these two actions, a series of armed incidents took place between Peruvian and Colombian rubber tappers in the area.[84][85] In 1908 around one hundred and twenty Peruvian soldiers were sent to the region to help Arana's rubber collecting firm, the Peruvian Amazon Company[86] to expel the Colombians from the Putumayo region.[87] The settlements of La Reserva, La Union, and El Dorado were the last significant Colombian settlements in the Putumayo at that time. The Peruvian combined force raided then burned down La Reserva and La Union,[88] before threatening the inhabitants of El Dorado with death if they did not flee the area.[89]

Vásquez Cobo-Martins Treaty

[edit]On April 24, 1907, it was signed in Bogotá, between the representatives of the governments of Colombia and Brazil; Alfredo Vásquez Cobo and Enéas Martins, respectively, a treaty that defined the border, between the Cocuy stone to the mouth of the Apaporis River in Caquetá.[90]

Porras-Tanco Argáez Treaty

[edit]| Type | Friendship treaty |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 1909 |

| Signed | 21 April 1909 |

| Location | Lima |

| Signatories |

In 1909, negotiations were resumed between Peru and Colombia, in order to put an end to the conflict taking place between Putumayo and Caquetá. The Peruvian foreign minister, Melitón Porras, and the Colombian minister, Luis Tanco Argáez, signed an agreement on April 22 of that year, which consisted of the following points:[91]

- The appointment of a commission to investigate the events in Putumayo and establish responsibilities.

- The material damages and the families of the victims would be compensated.

- The question of limits would be resolved when the Spanish ruling was issued in the lawsuit with Ecuador and would be submitted to arbitration in case of disagreement.

- A new modus vivendi would be agreed upon.

- A trade agreement would be adjusted.

In compliance with the first part of the treaty, the convention on claims was signed in Bogotá on April 13, 1910. The constitution of an international mixed tribunal that would meet in Rio de Janeiro 4 months after the signing of the convention was agreed upon. The court had to decide:[91]

- The amount of compensation that one of the countries had to pay to another

- Determine the cases in which Colombian or Peruvian law should be applied to those presumed guilty of crimes in the region.

However, regarding the arbitration and modus vivendi agreements agreed upon in the Porras-Tanco Argáez treaty, no formal agreement was reached.

La Pedrera Conflict

[edit]In 1911, Colombia began to establish military garrisons on the left bank of the Caquetá River, in clear violation of the Porras-Tanco Argáez treaty, which established that this area was Peruvian territory. An expedition commanded by General Isaac Gamboa, made up of 110 men, occupied Puerto Córdoba, also called La Pedrera. In June, another expedition sailed to Puerto Córdoba under the command of General Neyra.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian government, safeguarding its interests in the area that were being threatened by the Colombian expeditions, requested the suspension of the Neyra expedition, but was denied. Then, the Loreto authorities sent out a Peruvian contingent, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Óscar R. Benavides, to evict the Colombians from La Pedrera.[92]

It was then that the consuls of Peru and Colombia in Manaus, aware of the consequences of a possible confrontation, telegraphically proposed to their governments the diversion of the expeditions: the Colombian expedition, commanded by Neyra, would stop in Manaus; and the Peruvian, from Benavides, in Putumayo.

However, due to lack of knowledge of these negotiations, an armed clash took place between the Peruvian and Colombian forces. On July 10, Benavides demanded the withdrawal of the Colombians from La Pedrera, which was denied. For this reason, the attack on Puerto Córdoba began: after two days of fighting, the Colombian contingent was forced to withdraw.[93][94][95]

On July 19, 1911, a week after the clashes in La Pedrera, the Peruvian Minister Plenipotentiary Ernesto de Tezanos Pinto and the Colombian Foreign Minister Enrique Olaya Herrera signed the Tezanos Pinto-Olaya Herrera Agreement in Bogotá. In this agreement, Colombia undertook not to increase the contingent located in Puerto Córdoba and not to attack the Peruvian positions located between Putumayo and Caquetá. At the same time, the Peruvian troops were forced to abandon La Pedrera and return the captured war trophies to the Colombians.[96][97]

Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty

[edit]On July 15, 1916, the plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador, Alberto Muñoz Vernaza; and that of Colombia, Fidel Suárez, signed in Bogotá the Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty, a boundary treaty between the two republics, from the Mataje River to the mouth of the Ambiyacú River in the Amazon:[98]

Starting from the mouth of the Mataje River, in the Pacific Ocean, upstream of said river, to (...) the divortium aquarum between the Putumayo River and the Napo River, and through this divortium aquarum to the main source of the Ambiyacu River, and by the course of this river to its mouth in the Amazon River: it being understood that the territories located on the northern margin of the Amazon and included between this border line and the limit with Brazil, belong to Colombia, which for its part leaves in Except for the possible rights of third parties.

Peru duly made a reservation of its rights affected by said pact.[99]

Colombia–Peru negotiations

[edit]After the La Pedrera incident, relations between Colombia and Peru were disturbed: Colombian civilians stoned the house of the Peruvian ambassador in Bogotá and their press attacked the attitude of their government. The separation of Panama, a very sensitive episode, was still in the collective mind, being referred to when talking about Caquetá. Meanwhile, the foreign ministries of both countries were concerned with initiating new negotiations. Between 1912 and 1918, both countries insisted on the idea of arbitration. Colombia, led by the conservatives, proposed the arbitration of the Pope: Peru, on the other hand, proposed as arbitrator the Court of The Hague or the President of the Swiss Confederation.

In 1919, a new phase of the conflict began. Colombia proposes a direct settlement, however, the line proposed by Colombian Minister Fabio Lozano Torrijos to the Peruvian Foreign Ministry was not accepted, since it did not imply any cession by Colombia. The Peruvian counterproposal was also not accepted by the Colombian minister.[99]

Salomón–Lozano Treaty

[edit]

Once the negotiations were restarted, on March 24, 1922, a direct agreement was reached in Lima, the work of the plenipotentiaries Fabio Lozano Torrijos (representing Colombia) and Alberto Salomón Osorio (representing Peru). The Salomón-Lozano treaty established the following limit:

The border line between the Peruvian Republic and the Republic of Colombia is agreed, agreed and fixed in the terms that are expressed below: From the point where the meridian of the mouth of the Cuhimbé River in Putumayo intersects the San Miguel River or Sucumbíos, go up that same meridian to said mouth of the Cuhimbé; from there by the Putumayo River to the confluence of the Yaguas River; follows a straight line that from this confluence goes to the Atacuari River in the Amazon and from there through the Amazon River to the border between Peru and Brazil established in the Peru-Brazilian Treaty of October 23, 1851.[100]

The rectification of the boundary between Peru and Brazil and the delivery of the strip of territory bordering Brazil, by the line agreed in 1851 with Peru, as well as Colombia's access to the Amazon, of which only Peru and Brazil were condominium owners, determined Brazil's opposition to the Salomón-Lozano treaty. This attitude delayed the approval of the agreement, until the signing of an act in Washington in 1925, by which Colombia recognized the territories ceded by Peru to Brazil in 1851.[101] On December 20, 1927, it was approved by the Peruvian Congress, it would be ratified by the Colombian on March 17, 1928, and became effective on March 19, 1928. Finally, the treaty was consummated with the physical delivery of the territories on August 17, 1930.

In Peru, Leguía is still criticized for signing this treaty, considered excessively inconvenient, as it delivered over 300,000 km2, a considerable part occupied by Peruvian citizens, to Colombia. However, the intention of the Peruvian government was to gain an ally for Peru, when it was overwhelmed by the conflicts with Ecuador and Chile. Indeed, one consequence of the treaty was that Colombia supported Peru in the Peruvian-Ecuadorian dispute and that Ecuador broke off its relations with Colombia.[102]

Colombia–Peru War

[edit]

The Colombia–Peru War was the result of dissatisfaction with the Salomón–Lozano Treaty and the imposition of heavy tariffs on sugar. On August 27, 1932, Peruvian civilians Oscar Ordoñez and Juan La Rosa Guevara, in the presence of Lieutenant Colonel Isauro Calderón, Lieutenant Commander Hernán Tudela y Lavalle, engineers Oscar H. Ordóñez de la Haza and Luis A. Arana, doctors Guillermo Ponce de León, Ignacio Morey Peña, Pedro del Águila Hidalgo and Manuel I. Morey created the National Patriotic Junta (Spanish: Junta Patriótica Nacional), known also as the Patriotic Junta of Loreto (Spanish: Junta Patriótica de Loreto).[103][104][105] They obtained, through donations and charity from civilians and the military, the necessary weapons and resources to start the “recovery of the port”.[106]

The group released an irredentist manifesto known as the Leticia Plan (Spanish: Plan de Leticia) denouncing the Salomón-Lozano Treaty.[107] The "plan" would be carried out peacefully and force would only be used if Colombia authorities responded in a hostile manner. Civilians would be the only ones participating so as not to compromise the entire country, which led to Juan La Rosa Guevara renouncing his appointment as second lieutenant in order to participate as a civilian.[108] The takeover of Leticia, originally planned for September 15, 1932, was brought forward two weeks. The center of operations was the border city of Caballococha, whose inhabitants joined the Civilian Recovery Army, whose number was 48 people.

In the early hours of September 1, 1932, what is now known as the Leticia Incident took place after Leticia was seized with the support of the local population. As a result, Colombian authorities and police fled to nearby Brazil. On 1 September 1932, President Luis Miguel Sánchez dispatched two regiments of the Peruvian Army to Leticia and Tarapacá; both settlements were in the Amazonas Department, now in southern Colombia. Those actions were then mostly ignored by the Colombian government.[109]

The situation would escalate, however, as Colombia would sever relations with Peru in February 1933, and both countries would battle each other until President Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro's assassination on the same year by an APRA member.

Rio Protocol

[edit]The commission to settle the dispute over Leticia met in Rio de Janeiro in October 1933. The Peruvian side was made up of Víctor M. Maúrtua, Víctor Andrés Belaúnde, Alberto Ulloa Sotomayor, and Raúl Porras Barrenechea. The Colombian delegation, by Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luis Cano Villegas and Guillermo Valencia Castillo.

Peru invited Ecuador to begin negotiations in order to settle the question of pending limits between the two countries, which it refused. The country was an interested party in the dispute between Colombia and Peru, not only because of territorial contiguity, but also because there was an area that the three countries claimed. The Ecuadorian Congress declared that it would not recognize the validity of the arrangements between its two neighbors.

On May 24, 1934, the diplomatic representations of Colombia and Peru signed the Protocol of Rio de Janeiro, in the city of the same name, ratifying the Salomón-Lozano treaty, still in force today and accepted by both parties, and finally ending the territorial dispute.

See also

[edit]- Bolivian–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Ecuadorian–Peruvian territorial dispute

- Colombia–Peru relations

- Dispute resolution

- Territorial dispute

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Ecuador and Colombia signed the Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty in 1916, ending their dispute.

References

[edit]- ^ "La corona española crea el Virreinato de la Nueva Granada". Luis Ángel Arango Library. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06.

- ^ "Se suprime el recién creado Virreinato de la Nueva Granada". Luis Ángel Arango Library. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06.

- ^ "Se restablece el Virreinato de la Nueva Granada". Luis Ángel Arango Library. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, 1926: 13–14

- ^ Aranda, Ricardo (1890). Colección de los tratados, convenciones capitulaciones, armisticios, y otros actos diplomáticos (in Spanish). Imprenta del estado. p. 227.

- ^ Cayo Córdoba, Percy (1995). PERÚ Y ECUADOR: Antecedentes de un Largo Conflicto (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Lima: Universidad del Pacífico. ISBN 9789972603013.

- ^ Ulloa, Luis (1911). Algo de historia. Las cuestiones territoriales con el Ecuador y Colombia y la falsedad del Protocolo Pedemonte-Mosquera (in Spanish). La Industria. p. 119.

- ^ Parodi, Carlos A. (2002). The Politics of South American Boundaries. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 5–8. ISBN 0-275-97194-5.

- ^ Castell, 1981, Vol. 3: 1055

- ^ Tauro del Pino 2001, Vol. 7, p. 1115.

- ^ Cuerpo de leyes de la República de Colombia, que comprende todas las leyes, decretos y resoluciones dictados por sus congresos desde el de 1821 hasta el último de 1827 (in Spanish). Caracas: Imprenta de Valentín Espinal. 1840. pp. 207–2011.

- ^ Belaúnde 1997, p. 2–10.

- ^ Reglamento Provisional de 1821 (12 de febrero de 1821) (in Spanish). Huaura: Congress of Peru. 1821.

- ^ Vargas Ugarte 1981, Vol. 7, p. 172-173.

- ^ Gaceta del Gobierno del Perú Independiente, 28 July 1821.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 23.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 24-25.

- ^ Gran Historia del Perú (2000), p. 251.

- ^ Gran Historia del Perú (2000), p. 252.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 25.

- ^ Belaúnde (1997), p. 109.

- ^ Basadre (2005), Vol. 2, p. 13

- ^ Gran Historia del Perú (2000), p. 252-253.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea (1926), p. 25.

- ^ Basadre (2005), Vol. 1, p. 271.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 26.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 1, p. 278.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 1, p. 280–281.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 27.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 24-27.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 2, p. 13-14.

- ^ "13 de mayo de 1830; Nacimiento de la República del Ecuador". Biblioteca Municipal de Guayaquil. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07.

- ^ "Proclamación de la separación de Venezuela de la Gran Colombia". Luis Ángel Arango Library. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06.

- ^ Picón, Delia (1999). Historia de La Diplomacia Venezolana: 1811-1985 (in Spanish). Andrés Bello Catholic University. p. 101. ISBN 9802442046.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 28.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 2, p. 17-19.

- ^ Aguilera Peña, Mario. "División política-administrativa de Colombia". Banco de la República.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 32.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 2, p. 24.

- ^ Bustillo, p. 17.

- ^ Ley del 21 de noviembre de 1832 (PDF). Congress of Peru. 1832.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 2, p. 237-239.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 2, p. 239-240.

- ^ a b Basadre, Vol. 2, p. 241.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 58.

- ^ Bustillo, p. 19-20.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 84.

- ^ Bustillo, p. 20.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 5, p. 136.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 34.

- ^ López Domínguez, Luis Horacio (1993). Relaciones Diplomáticas de Colombia y la Nueva Granada: Tratados y Convenios 1811-1856. ISBN 958-643-000-6. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2022-08-15.

- ^ "Ley del 15 de junio de 1857 que erige en estados diversas porciones de la República". Luis Ángel Arango Library.

- ^ Sinopsis de la Frontera Colombia-Ecuador (PDF) (in Spanish). Bogotá: Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 60.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 37.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 37-39.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 10, p. 215-217

- ^ Salamanca 1912, p. 17.

- ^ Bustillo 1916, p. 31.

- ^ Bustillo 1916, p. 34.

- ^ Bustillo 1916, p. 35.

- ^ a b Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 40.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 46-48.

- ^ Bustillo 1916, p. 38.

- ^ a b Bustillo 1916, p. 39.

- ^ Uribe Vargas, Diego (2005). Colombia y la diplomacia secreta: gestiones para implantar la monarquía (in Spanish). Bogotá: Universidad de Bogotá. pp. 195–199. ISBN 9789589029770.

- ^ Salamanca 1912, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 49.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 12, p. 192.

- ^ Salamanca 1912, p. 79-80.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 12, pp. 193-194.

- ^ Salamanca 1912, pp. 84.

- ^ Basadre 2005, Vol. 12, pp. 194.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, pp. 50.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, pp. 75.

- ^ a b Valcárcel 2004, pp. 51.

- ^ Valcárcel 2004, pp. 52.

- ^ Rey de Castro, p. 155.

- ^ Valcárcel, p. 53.

- ^ a b Palacios y Safford, p. 515.

- ^ Valcárcel, p. 15-17.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 50-51.

- ^ Salamanca, p. 87-88.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 51.

- ^ Casement, Roger (1997). The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement. Anaconda Editions. p. 356. ISBN 978-1-901990-05-8.

- ^ Hardenburg, Walter (1912). The Putumayo, the Devil's Paradise; Travels in the Peruvian Amazon Region and an Account of the Atrocities Committed Upon the Indians Therein. London: Fischer Unwin. p. 132.

- ^ Taussig, Michael (2008). Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. University of Chicago Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-226-79011-4.

- ^ Hardenburg, Roger (1912). The Putumayo, the Devil's Paradise; Travels in the Peruvian Amazon Region and an Account of the Atrocities Committed Upon the Indians Therein. London: Fischer Unwin. pp. 174–175, 177.

- ^ Tratado de Límites entre Colombia y Brasil (PDF) (in Spanish). Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia. 1907.

- ^ a b Porras Barrenechea, p. 51-52.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 52.

- ^ Bustillo, p. 72.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, p. 53.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 12, p. 265.

- ^ Bustillo, p. 73-74.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 12, p. 266.

- ^ Tratado de Límites entre las Repúblicas de Colombia y Ecuador (Tratado Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez) (PDF). Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia. 1916.

- ^ a b Porras Barrenechea, p. 54.

- ^ "Tratado de Límites y Navegación Fluvial entre las Repúblicas de Colombia y Perú (Tratado Salomón-Lozano)" (PDF). Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, pp. 79.

- ^ Basadre, Vol. 14, p. 123-125.

- ^ Ávila Sánchez, Vanessa C. (2017-06-01). "The war between Colombia and Perú (1932-1934). A perspective from the venezuelan press". Scielo.

- ^ "En el Perú hay manifestaciones por la revisión del tratado de límites con Colombia". El Universal. 1932-09-06.

- ^ Ugarteche, 1969. p. 186

- ^ Atehortúa Cruz, Adolfo León (2007). EL CONFLICTO COLOMBO – PERUANO: Apuntes acerca de su desarrollo e importancia histórica (PDF) (in Spanish). Bogotá: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. p. 3.

- ^ "CONMEMORACION DE LA TOMA DE LETICIA 1932". Municipalidad Ramón Castilla. 2021-09-01. Archived from the original on 2021-09-24. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ Compendio de la Historia General del Ejército del Perú. Biblioteca General y Aula Virtual del Ejército. 2015.

- ^ "La guerra con el Perú". Red Cultural del Banco de la República.

Bibliography

[edit]- Angulo Puente Arnao, Juan (1908). Nuestra cuestión de límites con las repúblicas de Ecuador y Colombia (PDF). Imprenta Tipográfica de La Opinión.

- Angulo Puente Arnao, Juan (1927). Historia de los límites del Perú. Intendencia General de la Guerra.

- Basadre Grohmann, Jorge (2005). Historia de la República del Perú (1822-1933). Empresa Editora El Comercio S. A. ISBN 9972-205-62-2.

- Porras Barrenechea, Raúl (1926). Historia de los límites del Perú (PDF). Librería Francesa Científica y Casa Editorial E. Rosay.