Game Boy

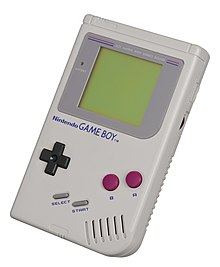

The original gray Game Boy | |

| Also known as | DMG-01

|

|---|---|

| Developer | Nintendo R&D1 |

| Manufacturer | Nintendo |

| Product family | Game Boy |

| Type | Handheld game console |

| Generation | Fourth |

| Release date | |

| Introductory price | |

| Discontinued |

|

| Units sold | 118.69 million (including all variants and Game Boy Color)[11] |

| Media | Game Boy Game Pak |

| System on a chip |

|

| CPU | Sharp SM83 @ 4 MHz |

| Memory | 8 KB RAM, 8 KB VRAM |

| Display | |

| Best-selling game | Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow (46 million units) |

| Predecessor | Game & Watch |

| Successor | Game Boy Color |

The Game Boy is a handheld game console developed by Nintendo, launched in the Japanese home market on April 21, 1989, followed by North America later that year and other territories from 1990 onwards. Following the success of the Game & Watch single-game handhelds, Nintendo developed the Game Boy to be more like a portable console, with interchangeable cartridges. The concept proved highly successful and the Game Boy became a cultural icon of the 1990s and early 2000s.

The Game Boy was designed by the Nintendo Research & Development 1 team, led by Gunpei Yokoi and Satoru Okada. The device features a dot-matrix display, a directional pad, four game buttons, a single speaker, and uses Game Pak cartridges. The two-toned gray design with black, blue, and dark magenta accents sported softly rounded corners, except for the bottom right, which was curved. At launch, it was sold either as a standalone unit or bundled with games like Super Mario Land and Tetris.

Despite mixed reviews criticizing its monochrome graphics and larger size compared to competitors like the Sega Game Gear, Atari Lynx, and NEC TurboExpress, the Game Boy rapidly outsold them all. An estimated 118.69 million units of the Game Boy and its successor, the Game Boy Color (1998), have been sold worldwide, making it the fourth-best-selling console ever. The Game Boy received several redesigns during its lifespan, including the smaller Game Boy Pocket (1996) and the Game Boy Light (1998). Sales of Game Boy variants continued until 2003.

Development

[edit]The Game Boy was designed by the team at Nintendo Research & Development 1 (R&D1), which had previously developed the Game & Watch handhelds and video games including Mario Bros. and Donkey Kong.[12][13] However, early in the process, deep disagreements arose between Gunpei Yokoi, the R&D1 division director, and Satoru Okada, the assistant director. Yokoi's original vision was for a simpler device, akin to an advanced Game & Watch, while Okada strongly advocated for a more powerful device with interchangeable cartridges, like a portable version of the successful Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Their differing visions for the project led to frequent clashes, heated meetings and high tensions, with Okada ultimately convincing Yokoi of his vision.[14]

The team was encouraged to pursue the project by Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi. However within Nintendo, many were skeptical that such a device would be feasible. Some employees even gave the project the derogatory nickname "DameGame" (dame (だめ) meaning "hopeless" in Japanese).[15][16]

The codename for this nascent project was "Dot Matrix Game" (DMG), reflecting its intended display technology, a stark contrast to the Game & Watch series, which had segmented LCDs pre-printed with an overlay, limiting each model to only play one game. The initials DMG came to be featured on the final product's model number: "DMG-01."[17]

Originally, a Ricoh-manufactured CPU, similar to the one used in the NES, was considered for compatibility.[18] However, due to resource constraints amid the ongoing development of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, the Game Boy team chose a less powerful CPU from the Sharp Corporation.[19]

Sharp initially showed reluctance to engage in the project, particularly for the LCD technology, which was a critical component.[19] The team considered buying displays from the Citizen Watch Company which was already using LCD screens to build portable TVs. However, talks continued with Sharp, with Yokoi and Okada showing the company a Game Boy mockup. After seeing the device and wanting to keep Nintendo as a client, Sharp offered competitive pricing and secured the contract.[18] Sharp originally proposed a twisted nematic (TN) display, but after seeing a prototype Game Boy, Yamauchi rejected the TN technology as too hard to see. Sharp then suggested super-twisted nematic (STN) technology, which had better viewing angles and contrast but was more expensive. To reduce cost, the team reduced the screen size, however, it was too late in the development process to shrink the console's overall size.[19][20]

Within R&D1, Yokoi had long promoted "lateral thinking with withered technology",[a] a design philosophy which eschewed cutting-edge technology in favor of using mature technologies, which tended to be more affordable and reliable, in innovative ways.[12] As a result of this philosophy, to keep costs low and extend battery life, the Game Boy was designed without a backlight and used a simple grayscale screen, despite potential concerns about visibility and the lack of color.[21] The approach was ultimately vindicated as rival units with full-color, backlit screens were panned for their dismal battery life, making the Game Boy more appealing to consumers.[12]

In the early 1980s, Okada had worked on an electronic game from Nintendo called Computer Mah-jong Yakuman that allowed cable communication between two devices, he thought it would be possible to implement a similar feature in the Game Boy.[19][22] Despite concerns within the team that the feature would be too difficult to use and thus a waste of resources, Okada pushed forward and developed the Game Link Cable technology himself.[18] This effort led to the creation of the "battle" and "trade" gameplay features in the Pokémon series, first released in 1996.[19]

A prototype Game Boy was unveiled in 1987 and later exhibited at multiple industry trade shows. The device incorporated a key design element developed by Yokoi and his team at R&D1 for its Game & Watch predecessor: the directional control pad, often referred to as the "D-pad." Yokoi had recognized that traditional joysticks might hinder the portability of handheld devices. As a result, he designed the D-pad – a flat controller that extends just slightly beyond the device's casing. A similar layout had been used on the NES, making it easier for owners to transition to the handheld. Yamauchi estimated that the console would achieve sales exceeding 25 million units in its initial three years, a claim that was regarded as bold at the time.[12]

Nintendo's philosophy centered on the belief that the appeal of a gaming system was primarily determined by the quality of its games. With this in mind, Okada pushed to make development tools available for third-party developers, a shortcoming of the launch of the NES.[18] R&D1 also developed Super Mario Land, a portable adaptation of the Super Mario Bros. game, intending it to be the flagship title for the Game Boy.[23] However, Henk Rogers brought the Soviet Union-made game, Tetris, to the attention of Nintendo of America. Despite its simple graphics and lack of a well-known brand, Tetris's suitability for a handheld platform convinced Nintendo president Minoru Arakawa to port and bundle it with the Game Boy. As a result, Tetris was bundled with the Game Boy in every region except Japan on its release.[12]

The Game Boy launched in the Japanese market in April 1989, followed by North America in July, and Europe in September of the following year,[23] backed by a $10 million marketing effort.[24] Sales of the Game Boy and its successor variants (including the Game Boy Color) continued until March 2003.

Hardware

[edit]

The Game Boy uses a custom system on a chip (SoC), to house most of the components, named the DMG-CPU by Nintendo and the LR35902 by its manufacturer, the Sharp Corporation.[25]

Within the DMG-CPU, the main processor is a Sharp SM83,[26] a hybrid between two other 8-bit processors: the Intel 8080 and the Zilog Z80. The SM83 has the seven 8-bit registers of the 8080 (lacking the alternate registers of the Z80), but uses the Z80's programming syntax and extra bit manipulation instructions, it also adds new instructions to optimize the processor for certain operations related to the way the hardware was arranged.[12][25][27][28] The Sharp SM83 operates at a clock rate of 4.194304 MHz.[25]

The DMG-CPU also incorporates the Picture Processing Unit, essentially a basic GPU, that renders visuals using an 8 KB bank of Video RAM located on the motherboard.[25] The display itself is a 2.5-inch (diagonal) reflective super-twisted nematic (STN) monochrome liquid-crystal display (LCD), measuring 47 millimeters (1.9 in) wide by 43 millimeters (1.7 in) high. The screen can render four shades with a resolution of 160 pixels wide by 144 pixels high in a 10:9 aspect ratio.[29][30]

The SoC also contains a 256 B "bootstrap" ROM which is used to start up the device, 127 B of High RAM that can be accessed faster (similar to a CPU cache), and the Audio Processing Unit, a programmable sound generator with four channels: a pulse wave generation channel with frequency and volume variation, a second pulse wave generation channel with only volume variation, a wave channel than can reproduce any waveform recorded in RAM, and a white noise channel with volume variation.[25][31][32][33] The motherboard also contains a 8 KB "working RAM" chip.[25]

The Game Boy features a D-pad (directional pad), four buttons labeled 'A', 'B', 'SELECT', 'START', and a sliding power switch with a cartridge lock to prevent removal. The volume and contrast are adjusted by dials on either side.[34] The original Game Boy was powered internally by four AA batteries.[35] For extended use, an optional AC adapter or rechargeable battery pack can be connected via a coaxial power connector on the left side.[36] The Game Boy has a single monaural speaker and a 3.5 mm stereo headphone jack.[37] The right side offers a Game Link Cable port[b] for connecting to another Game Boy for two-player games or, notably in Pokémon, sharing files.[39] This port can also be used with a Game Boy Printer.

Technical specifications

[edit]| Game Boy[29][40] | Game Boy Pocket[40] | Game Boy Light | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 148 mm (5.8 in) | 127.6 mm (5.02 in) | 135 mm (5.3 in) |

| Width | 90 mm (3.5 in) | 77.6 mm (3.06 in) | 80 mm (3.1 in) |

| Depth | 32 mm (1.3 in) | 25.3 mm (1.00 in) | 27 mm (1.1 in) |

| Weight | 220 g (7.8 oz) | 125 g (4.4 oz) | 138 g (4.9 oz) |

| Display | 2.5-inch reflective super-twisted nematic (STN) liquid-crystal display (LCD) | 2.5-inch film compensated STN (FSTN) LCD | 2.5-inch FSTN LCD with electroluminescent backlight |

| Screen size (playable)[41] | 45.5 mm × 41.5 mm (1.79 in × 1.63 in) | 47.5 mm × 42.5 mm (1.87 in × 1.67 in) | 47 mm × 42 mm (1.9 in × 1.7 in) |

| Resolution | 160 (w) × 144 (h) pixels (10:9 aspect ratio) | ||

| Frame rate | 59.727500569606 Hz[42] | ||

| Color support | 2-bit, four shades of green: 0x0 0x1 0x2 0x3 | 2-bit, four shades of grey: 0x0 0x1 0x2 0x3 | |

| System on a chip (SoC) | Nintendo DMG-CPU (Sharp LR35902) | Nintendo CPU MGB | |

| Processor | 4.194304 MHz Sharp SM83 (custom Intel 8080/Zilog Z80 hybrid, 8-bit) | ||

| Memory |

| ||

| External: (in the game cartridge) up to 1 MB ROM, up to 128 KB RAM | |||

| Power |

|

|

|

| Battery life | Up to 30 hours | Up to 10 hours |

|

| Sound |

| ||

| I/O |

| ||

| Controls |

| ||

Revisions

[edit]

The Game Boy continued to experience strong sales well into the 1990s, as popular games continued to increase interest in the handheld. This commercial success was something of a double-edged sword for Nintendo; the device was seen as aged, but the company was unwilling to abandon it. Instead, the company embarked on a series of improvements to the Game Boy in an effort to keep the console relevant.[12]

Play It Loud!

[edit]The first revision to the Game Boy came on March 20, 1995, when Nintendo released several special edition Game Boy models with colored cases, advertising them in the "Play It Loud!" campaign,[43] known in Japan as Game Boy Bros.[c] Play It Loud! units were manufactured in red, yellow, green, blue black, white, and clear (transparent). The Play It Loud's screens also have a darker border than the normal Game Boy.[44]

Game Boy Pocket

[edit]A major revision to the Game Boy came in 1996 with the introduction of the Game Boy Pocket, a slimmed-down unit that required just two smaller AAA batteries, albeit at the expense of providing just 10 hours of gameplay.[45] The other major change was that the screen was changed to a film compensated super-twisted nematic (FSTN) LCD. This film compensation layer produced a true black-and-white display, rather than the green hues of the original Game Boy.[46] The Pocket also has a smaller Game Link Cable port, which requires an adapter to link with the original Game Boy. This smaller port design would be used on all subsequent Game Boy models.[47] Internally, the Game Boy Pocket had a new SoC, the Nintendo CPU MGB, an improved version of the DMG-CPU. A major change was that the device's 8 KB of Video RAM was moved from the motherboard to the SoC for faster access.[25][48]

The Game Boy Pocket was released in Japan on July 20, 1996, and in North America on September 2, 1996, for US$69.99 (equivalent to $136 in 2023).[49] The Game Boy Pocket revitalized hardware sales and its release was ultimately well-timed as it coincided with the release of the first Pokémon game, which catapulted the Game Boy into uncharted realms of commercial triumph.[12] Reviewers praised the device's small size,[50] and said that the screen's visibility and pixel response-time had been improved, mostly eliminating ghosting.[51] However, other reviewers were dismissive of the device, with the Los Angeles Times saying Nintendo was "repacking the same old black-and-white stuff and selling it as new."[52]

The first version came only in silver and did not have a power LED. A revision in early 1997 added a power LED, different case colors (red, green, yellow, black, gold metal, clear, and blue) and dropped the price to US$54.95 (equivalent to $104 in 2023).[53] By mid-1998, just months before the Game Boy Color went on sale, prices had fallen to US$49.95 (equivalent to $93 in 2023).[54]

Game Boy Light

[edit]The Game Boy Light was a Japan-only revision released on April 14, 1998. Like the Game Boy Pocket, the system was priced at ¥6,800 (equivalent to ¥6,892 in 2019).[55] The Game Boy Light is slightly bigger than the Game Boy Pocket and features an electroluminescent backlight allowing it to be played in low-light conditions. It uses two AA batteries, which give it approximately 12 gameplay hours with the backlight on and 20 with it off.[55] It was available in two standard colors: gold and silver.[55][56]

Games

[edit]

More than 1,000 games were released for the Game Boy, excluding cancelled and unlicensed games.[57] Additionally, more than 300 games developed for the Game Boy Color were forward compatible with the monochrome Game Boy models.[58][59]

Games are stored on cartridges called the Game Boy Game Pak, using read-only memory (ROM) chips. Initially, due to the limitations of the 8-bit architecture of the device, ROM size was limited to 32 KB. However, Nintendo overcame this limitation with a Memory Bank Controller (MBC) inside the cartridge. This chip sits between the processor and the ROM chips. The CPU can only access 32 KB at a time, but the MBC can switch between several banks of 32 KB ROM. Using this technology, Nintendo created Game Boy games that used up to 1 megabyte of ROM. Game Paks could also provide additional functionality to the Game Boy system. Some cartridges included up to 128 KB of RAM to increase performance, which could also be battery-backed to save progress when the handheld was off, real-time clock chips could keep track of time even when the device was off and Rumble Pak cartridges added vibration feedback to enhance gameplay.[25][60][61]

The top-selling franchise for the Game Boy were Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow, the first installments of the Pokémon video game series, which sold more than 46 million copies.[62][63] The best-selling single game was Tetris, with more than 35 million copies shipped, it was a pack-in game included with the purchase of many original Game Boy devices.[64][65]

Launch titles

[edit]When the Game Boy was released in Japan in April 1989 alongside four launch titles: Alleyway (a Breakout clone), Baseball (a port of the NES game), Super Mario Land (an adaptation of the Mario franchise for the handheld format) and Yakuman (a Mahjong game).[66] When the console was introduced in North America, two more launch titles were added: Tetris and Tennis (another NES game port), while Yakuman was never released outside of Japan.[67][68]

Reception

[edit]

Critical reception

[edit]Though it was less technically advanced than the Sega Game Gear, Atari Lynx, NEC TurboExpress and other competitors, notably by not supporting color, the Game Boy's lower price along with longer battery life made it a success.[69][70] In its first two weeks in Japan, from its release on April 21, 1989, the entire stock of 300,000 units was sold; a few months later on July 31, 1989, 40,000 units were sold on its first release day.[23] It sold one million units in the United States within weeks.[71] More than 118.69 million units of the Game Boy and Game Boy Color combined have been sold worldwide, with 32.47 million units in Japan, 44.06 million in the Americas, and 42.16 million in other regions. By Japanese fiscal year 1997, before Game Boy Color's release in late 1998, 64.42 million units of the Game Boy had been sold worldwide.[72] At a March 14, 1994, press conference in San Francisco, Nintendo vice president of marketing Peter Main answered queries about when Nintendo was coming out with a color handheld system by stating that sales of the Game Boy were strong enough that it had decided to hold off on developing a successor handheld for the near future.[73]

In 1995, Nintendo of America announced that 46% of Game Boy players were female, which was higher than the percentage of female players for both the Nintendo Entertainment System (29%) and Super Nintendo Entertainment System (14%).[74] In 2009, the Game Boy was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame, 20 years after its introduction.[75]

The console received mixed reviews from critics. In a 1997 year-end review, a team of four Electronic Gaming Monthly editors gave the Game Boy scores of 7.5, 7.0, 8.0, and 2.0. The reviewer who contributed the 2.0 panned the system due to its black-and-white display and motion blur, while his three co-reviewers praised its long battery life and strong games library, as well as the sleek, conveniently-sized design of the new Game Boy Pocket model.[76]

Sales

[edit]The Game Boy, Game Boy Pocket and Game Boy Color were commercially successful, selling a combined 118.69 million units worldwide: 32.47 million in Japan, 44.06 million in the Americas, and 42.16 million in all other regions.[77] At the time of its discontinuation in 2003, the combined sales of the Game Boy made it the best-selling game console of all time. In later years, its sales were surpassed by the Nintendo DS, PlayStation 2 and Nintendo Switch, making it the fourth-best-selling console of all time, as of 2024[update].[78]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ White, Dave (July 1989). "Gameboy Club". Nintendo Power. No. 7. p. 84.

- ^ "retrodiary: 1 April – 28 April". Retro Gamer. No. 88. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. April 2011. p. 17. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "Video Games Around the World: South Africa". Archived from the original on September 25, 2022.

- ^ "Соглашение Steepler и Nintendo". November 1994.

- ^ "Playtronic lança em abril Game Boy da Nintendo". folha.uol.com.br (in Portuguese). March 30, 1994. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ "Bajtek 1994 11". November 1994.

- ^ Edwards, Benj (April 21, 2019). "Happy 30th B-Day, Game Boy: Here are six reasons why you're #1". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Moriarty, Colin (October 15, 2013). "The Real Cost of Gaming: Inflation, Time, and Purchasing Power". IGN. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Console Crazy!". ACE. No. 37. September 1990. p. 142. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Freundorfer, Stephan (October 12, 2015). "Matsch-Screen statt Touchscreen". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. April 26, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McFarren, Damien (2016). Videogames Hardware Handbook. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 157–163. ISBN 978-1-78546-239-9.

- ^ "Satoru Okada talks Game & Watch, Game Boy and Nintendo DS development". Issue 163. Retro Gamer Magazine. 2016. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ Gorges, Florent (2019). L'Histoire de Nintendo Vol. 4: L'incroyable Histoire de la Game Boy [The History of Nintendo Vol.4: The Incredible History of the Game Boy] (in French). Châtillon: Omaké books. ISBN 978-2-919603-66-4.

- ^ Audureau, William (March 18, 2015). "NX, Ultra 64, Revolution… Petite histoire de Nintendo à travers ses noms de code". Le Monde.fr (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ "駄目". Wiktionary. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Lane, Gavin (May 6, 2020). "Nintendo Console Codenames and Product Codes". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kurokawa, Fumio (2022). "Satoru Okada – 2022 Retrospective Interview". 4gamer.net. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Aetas (July 15, 2022). "ゲームボーイの生みの親・岡田 智氏が任天堂での開発者時代を語った「黒川塾 八十八(88)」聴講レポート" [Attendance report on "Kurokawa Juku 88" where Game Boy creator Satoshi Okada talks about his time as a developer at Nintendo]. 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ Kurokawa, Fumio (March 29, 2022). "元任天堂・岡田 智氏の独立独歩 後編 ひたすらに意志を貫いたゲームボーイ&ゲームボーイアドバンス開発 「ビデオゲームの語り部たち」:第28部" [Former Nintendo employee Satoshi Okada's independent career, Part 2: The development of the Game Boy and Game Boy Advance with single-minded determination]. 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Ryan, Jeff (2011). Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America. New York: Portfolio Penguin. pp. 102–105. ISBN 978-1-59184-405-1.

- ^ Voskuil, Erik (March 19, 2011). "Mah-jong Yakuman". Before Mario: the fantastic toys from the video game giant's early days. Omaké books (published November 20, 2014). ISBN 978-2-919603-10-7. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Fahs, Travis (July 27, 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Game Boy". IGN. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Shiver Jr., Jube (November 29, 1989). "Toys: It's serious business as Nintendo's Game Boy goes head to head with Atari's Lynx". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Copetti, Rodrigo (February 21, 2019). "Game Boy / Color Architecture – A Practical Analysis". Archived from the original on April 13, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ Javanainen, Joonas (April 23, 2024). "Game Boy: Complete Technical Reference" (PDF). gekkio.fi. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Nintendo Game Boy, Part 1: The Intel 8080 and the Zilog Z80". RealBoy Emulator Blog. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ "CPU Comparison with Z80". Pan Docs. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "GameBoy User Manual". Nintendo of America. 1989. p. 12. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ Verhoeven, Jan (August 22, 2009). "Interrupt Descriptions". Using the GameBoy skeleton for serious business. Archived from the original on September 21, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Game Boy". 8bitcollective. November 5, 2008. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ GameBoy Development Wiki (November 12, 2009). "Gameboy Bootstrap ROM". Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Game Boy Advance Service Manual" (2nd ed.). Nintendo. p. 3. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "Game Boy Owner's Manual". Nintendo of America. 1989. p. 3. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ "Game Boy Owner's Manual". Nintendo of America. 1989. p. 6. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

Remove the cover on the back of the GAME BOY and insert the four AA batteries (supplied) as shown in the illustration.

- ^ "Nintendo Game Boy (DMG-001)". Vidgame.net. 2006. Archived from the original on February 11, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ "Game Boy Owner's Manual". Nintendo of America. 1989. p. 5. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

(10) Headphone jack (PHONES) — Connect the stereo headphones that come with the GAME BOY to enjoy the impressive sounds of games without disturbing others around you. (11) Speaker — A small built-in external speaker. It will turn on automatically if the headphones are not plugged into the headphones jack.

- ^ "Game Boy Owner's Manual". Nintendo of America. 1989. p. 8. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Masuyama, Meguro (2002). "Pokémon as Japanese Culture?". In Lucien King (ed.). Game On. New York, NY: Universe Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 0-7893-0778-2.

Pokémon allowed more than metaphorical communication; it made use of a system that created actual communication — a network game.

- ^ a b "Technical data". Nintendo of Europe GmbH. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "Game Boy Versions". RetroRGB. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "TASVideos / Platform Framerates". tasvideos.org. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Color it loud with hot new Game Boys; Game Boy reflects players own style with five exciting new colors". Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Oxford, David (February 14, 2019). "Boy, Oh Game Boy: Play It Loud!". Old School Gamer Magazine. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ "The Incredible Shrinking Game Boy Pocket". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 84. Ziff Davis. July 1996. p. 16.

- ^ "Game Boy Relaunched". Next Generation. No. 20. Imagine Media. August 1996. p. 26.

- ^ "Link Cable Adapter". Nintendo of Europe. Archived from the original on May 11, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ Javanainen, Joonas (July 18, 2023). "MGB-xCPU schematic" (PDF). GitHub. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ "1998 Sears Christmas Book, Page 161 – Christmas Catalogs & Holiday Wishbooks". christmas.musetechnical.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Cameron, Mike (September 19, 1996). "A game that's small enough to score where it counts". Hamilton Spectator. p. 11. Retrieved May 22, 2024 – via NewsBank.

- ^ "Pocket Cool". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 89. Ziff Davis. December 1996. p. 204.

- ^ Curtiss, Aaron (May 30, 1996). "The Expo Challenge: Dodging the Pretenders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ "Tidbits...". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 94. Ziff Davis. May 1997. p. 19.

- ^ "Nintendo unchallenged as big Boy in town". USA Today. July 29, 1998. p. 4D. Retrieved May 22, 2024 – via NewsBank.

- ^ a b c "Game Boy Lights Up". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 105. Ziff Davis. April 1998. p. 26.

- ^ ゲームボーイライト (in Japanese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on May 30, 1998. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "Game Boy (original) Games" (PDF). Nintendo of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Game Boy Color Games" (PDF). Nintendo of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Game List – Released Titles". GameBoy.com. Nintendo of America. January 19, 2001. Archived from the original on January 19, 2001. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Byers, Brendan. "Exploring the Gameboy Memory Bank Controller". Brendan's Website. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ "Game Boy Programming Manual" (PDF). December 3, 1999. p. 299. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ "'Pokken Tournament' and Pokemon's $1.5 Billion Brand". The Huffington Post. AOL. March 19, 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Clement, Jessica (May 2024). "All-time best-selling Pokémon games 2024". Statista. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Saltzman, Marc (June 12, 2009). "'Tetris' by the numbers". USA Today. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (June 1, 2009). "After 25 years, Tetris has sold 125 million copies". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ Swanson, Drew (January 5, 2023). "Remembering the Game Boy's Launch Titles". Game Rant. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Duncan, Andrew (April 21, 2019). "Game Boy Launch Titles". GameGrin. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Yakuman for Game Boy (1989) – MobyGames". Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "AtariAge – Lynx History". AtariAge. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

Eventually the Lynx was squeezed out of the picture and the handheld market was dominated by the Nintendo GameBoy with the Sega Game Gear a distant second.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (December 22, 2016). "A Time of Endings, Part 2: Epyx". The Digital Antiquarian. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ Kent, Steve L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games (1 ed.). Roseville, Calif.: Prima Publishing. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

According to an article in Time magazine, the one million Game Boys sent to the United States in 1989 met only half the demand for the product. That allotment sold out in a matter of weeks and its black and white (except for Konami/Factor 5 games and SeaQuest DSV), was shown in color like the Game Gear version.

- ^ "A Brief History of Game Console Warfare: Game Boy". BusinessWeek. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

Game Boy and Game Boy Color's combined lifetime sales reached 118.7 million worldwide, according to Nintendo's latest annual report.

- ^ "Cart Queries". GamePro. No. 71. IDG. August 1994. p. 14.

- ^ "Makers Of Games Focus On Girls". The Gainesville Sun. January 15, 1995. p. 15. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ "Ball, Game Boy, Big Wheel enter toy hall of fame". Rochester Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "EGM's Special Report: Which System Is Best?". Electronic Gaming Monthly 1998 Video Game Buyer's Guide. Ziff Davis. March 1998. p. 58.

- ^ "A Brief History of Game Console Warfare: Game Boy". BusinessWeek. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ "Lifetime sales of video game consoles worldwide as of February 2024". Statista. March 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website archived at the Wayback Machine

- Game Boy

- Products introduced in 1989

- Game Boy consoles

- 1980s toys

- 1990s toys

- 2000s toys

- Monochrome video game consoles

- Regionless game consoles

- Fourth-generation video game consoles

- Handheld game consoles

- Z80-based video game consoles

- Products and services discontinued in 2003

- Experimental musical instruments

- Discontinued handheld game consoles