Gabriel Figueroa

Gabriel Figueroa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 24, 1907 |

| Died | April 27, 1997 (aged 90) |

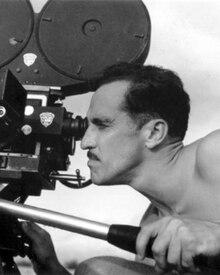

Gabriel Figueroa Mateos (April 24, 1907 – April 27, 1997) was a Mexican cinematographer who is regarded as one of the greatest cinematographers of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. He has worked in over 200 films, which cover a broad range of genres, and is best known for his technical dominance, his careful handling of framing and chiaroscuro, and affinity for the aesthetics of artists.

Early life and career

[edit]Born in 1907, Figueroa grew up in Mexico City, where he studied painting at the Academy of San Carlos, and violin at the National Conservatory.[1] He was the grandson of the famous lawyer, journalist and liberal writer Juan A. Mateos and first cousin to Mexican president Adolfo Lopez Mateos.[2] His mother died after giving birth to him and his father, unable to cope with the loss of his wife, left Gabriel and his brother Roberto to be cared for by their aunts. He then fled to Paris, where he eventually succumbed to alcohol and despair.[3][4] When the family fortune ran dry, Figueroa "had to leave the Academy and go into the darkroom to make a living".[1] He first started learning photography, which became his source of income, with Lalo Guerrero. He worked in a studio on Colonia Guerrero, where people would get their pictures taken with painted curtains in the background and under natural light.[5] Towards the end of the 1920s, Figueroa went on to work with photographers Juan de la Peña and José Guadalupe Velasco,[6] before establishing his own studio with his friend Gilberto Martínez Solares.[7]

In 1932, thanks to his friend Gilberto, Figueroa met cinematographer Alex Phillips. Convinced by his talent, Phillips managed to start Figueroa's career in the movie industry as a still photographer for the film Revolución (1933), directed by Miguel Contreras Torres.[2] Figueroa and Phillips would continue to work alongside each other on several other films.[8] As a result of marked growth in the field of Mexican film production, in 1933 Figueroa was able to continue and develop his work as a still photographer on at least 9 films, some of them of enormous significance in the history of national cinema.[9] Towards the end of June 1933, Figueroa made his debut as a cinematographer in several shots of the medium-length documentary El vuelo glorioso de Barberán y Collar (1933), directed by René Cardona. And, between October and November, he was one of the camera operators of the multiple sequences filmed for Viva Villa! (1934), directed by Jack Conway.[10] On November 13, 1934, Figueroa would begin working on the film Tribu (La Raza indómita) (1935) with fellow collaborator Miguel Contreras Torres, who Figueroa had his first job as a still photographer in 1932.[8] Tribu marked another milestone in Figueroa's career, as it was the first time he shared credit with his teacher Alex Phillips, in addition to his stillman work.[11]

In 1935, Rico Pani, son of prominent politician Alberto J. Pani, approached Figueroa with a contract to work as a cinematographer for a newly founded production company.[12] To consolidate his knowledge, he obtained from the magnate a scholarship to go study in Hollywood, seeing closely the work of Gregg Toland, then considered one of the best cinematographers in the world.[13] As a student, he saw Toland work on the film Splendor (1935) and learned how to create foreboding shadows and render a melancholy ambiance.[1][14] Upon arrival, Figueroa checked-in to the famous Roosevelt Hotel from where he called the only person he knew in the city, Charlie Kimball, editor of the movie Maria Elena (1936), of which Figueroa had worked as an illuminator and stillman in February 1935.[15] The call was answered by Gerardo Hanson, producer of Maria Elena, who later took him out to a villa on Vine Street.[16] Figueroa always considered Toland as his teacher.[17] The following year, in 1936, Gabriel returned to Mexico and it was here that he began to produce his distinctive images. His first feature, Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936), which would become one of the most popular films in Mexico and Latin America, and is considered to be the one that started the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, gained international recognition when it won a prize at the Venice Film Festival and broke box-office records.[3][18][19]

He filmed 235 movies over 50 years, including Los Olvidados by Luis Buñuel, The Fugitive by John Ford, Río Escondido by Emilio Fernández, and The Night of the Iguana by John Huston for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography in 1964.

One of his main collaborators was Fernández, with whom he shot twenty films, some of which won prizes at the Venice Film Festival, the Cannes Film Festival, and the Berlin Film Festival. After collaborating with Fernández and Buñuel on their films with such actors as Dolores del Río, Pedro Armendáriz, María Félix, Jorge Negrete, Columba Domínguez, and Silvia Pinal. Gabriel Figueroa has come to be regarded as one of the most influential cinematographers of México.

Filmography

[edit]Cinematographer

[edit]Camera operator

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | El vuelo glorioso de Barberán y Collar | René Cardona | |

| 1934 | Viva Villa! | Jack Conway | |

| 1936 | María Elena | Raphael J. Sevilla | also as Lighting technician |

| Let's Go with Pancho Villa | Fernando de Fuentes |

Still photographer

[edit]| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1933 | Revolution | Miguel Contreras Torres Antonio Moreno |

| Profanación | Chano Urueta | |

| 1934 | Almas encontradas | Raphael J. Sevilla |

| Enemigos | Chano Urueta | |

| Juarez and Maximilian | Miguel Contreras Torres Raphael J. Sevilla | |

| The Woman of the Port | Arcady Boytler Raphael J. Sevilla | |

| The Call of the Blood | José Bohr Raphael J. Sevilla | |

| Chucho el Roto | Gabriel Soria |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Nominated work | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | The Night of the Iguana | Best Cinematography | Nominated |

| Year | Nominated work | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | The Pearl | Best Cinematography | Won |

| Year | Work | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Bugambilia | Best Cinematography | Nominated |

| 1947 | Enamorada | Won | |

| 1948 | The Pearl | Won | |

| 1949 | Río Escondido | Won | |

| 1950 | Pueblerina | Won | |

| 1951 | Los Olvidados | Won | |

| 1952 | Víctimas del Pecado | Nominated | |

| 1953 | Soledad's Shawl | Won | |

| Cuando levanta la niebla | Nominated | ||

| 1954 | The Boy and the Fog | Won | |

| 1957 | La escondida | Nominated | |

| 1973 | María | Won | |

| 1974 | El señor de Osanto | Nominated | |

| 1975 | Presagio | Nominated | |

| 1976 | Coronación | Nominated | |

| 1978 | Divinas palabras | Won |

Film festivals

[edit]| Year | Festival | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Cannes Film Festival | Best Cinematography | María Candelaria The Three Musketeers |

Won | [20] |

| 1947 | Locarno International Film Festival | María Candelaria | Won | [21] | |

| Venice Film Festival | The Pearl | Won | [22] | ||

| 1949 | The Unloved Woman | Won | [23] |

Exhibition

[edit]- 2011: Rencontres d'Arles Festival, France.

- 2013-2014: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. Detailed retrospective of Figueroa's photography, cinematography, and progressive politics.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) organized the retrospective exhibition titled "Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film." The exhibit, featuring Figueroa's work from the early 1930s to the early 1980s, included film clips, paintings, photographs, posters and documents both from Figueroa's archive and the Televisa Foundation collections. "Under the Mexican Sky" recognizes Figueroa's contribution to Mexico's Golden Age of Film, both technically, and stylistically. LACMA curators highlight the artist's works across genres that "…helped forge an evocative and enduring image of Mexico." The exhibit ran from September 22, 2013, through February 2, 2014 in the Art of the Americas Building, Level 1.[24]

Tributes

[edit]On 24 April 2013, Google celebrated Gabriel Figueroa's 106th Birthday with a doodle.[25][26]

See also

[edit]- Emmanuel Lubezki

- Henner Hofmann

- Alfonso Cuarón

- Alejandro González Iñárritu

- Guillermo del Toro

- Adolfo López Mateos

- Esperanza López Mateos

- Rosalío Solano

- Cinema of Mexico

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Dey, Tom (September 18, 2019). "Gabriel Figueroa: Mexico's Master Cinematographer". American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b Maza, Maximiliano. "Directores del Cine Mexicano: Gabriel Figueroa". Más de Cien Años de Cine Mexicano. Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Reed (September 21, 2013). "The cinematic 'murals' of Gabriel Figueroa". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Isaac 1993, p. 20.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 19.

- ^ a b Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 49.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 52.

- ^ Preston, Julia (April 30, 1997). "Gabriel Figueroa Mateos, 90; Filmed Mexico's Panoramas". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 54.

- ^ Figueroa et al. 2008, p. 56.

- ^ "110 años de Gabriel Figueroa y la cinefotografía mexicana". April 24, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "Strachwitz Frontera Collection "Allá en el Rancho Grande:" The Song, the Movie, and the Dawn of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema". November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "La Visión del Mago. Gabriel Figueroa". June 26, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "Cannes Film Festival - 1946 Awards". IMDb. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ "Locarno International Film Festival - 1947 Awards". IMDb. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ "ASAC Data: Awards" (in Italian). Venice Biennale. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019.

- ^ "Venice Film Festival - 1949 Awards". IMDb. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ "Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film". LACMA. August 29, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Desk, OV Digital (2023-04-24). "24 April: Remembering Gabriel Figueroa on Birthday". Observer Voice. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Gabriel Figueroa's 106th Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

Sources

[edit]- Figueroa, Gabriel; Maillé, Mauricio; Monterde, Fernanda; Morales, Alfonso; Monterde, Claudia; Orozco, Héctor (2008). Gabriel Figueroa: Travesías de una mirada. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. ISBN 978-6-0775-1517-3. OCLC 761044362.

- Higgins, Ceri (2008). Gabriel Figueroa: Nuevas Perspectivas. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, Dirección General de Publicaciones. ISBN 978-6-0745-5080-1. OCLC 601690208.

- Isaac, Alberto (1993). Conversaciones con Gabriel Figueroa. Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro de Investigación y Enseñanza Cinematográficas. ISBN 978-968-895-421-8. OCLC 606317484.

- Feder, Elena (Spring 1996). "A Reckoning: Interview with Gabriel Figueroa". Film Quarterly. University of California Press. ISSN 0015-1386. OCLC 7021572304.

- Sánchez, Alberto Ruy; Figueroa, Gabriel; Tejeda, Roberto; Fuentes, Carlos; Mansilla, Margarita; de Orellana, Margarita; Monsiváis, Carlos; Tejada, Roberto; Cuevas, José Luis (Fall 1992). "Artes de México - EL ARTE DE GABRIEL FIGUEROA: SEGUNDA EDICION". Gustavo Pérez: Ceramica Contemporánea. Margarita de Orellana. ISSN 0300-4953.

External links

[edit]- Gabriel Figueroa's Official website (in Spanish)

- Gabriel Figueroa's Profile at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education website (in Spanish)

- Great Cinematographers - Gabriel Figueroa

- La Visión del Mago Gabriel Figueroa (in Spanish)

- Trayectora de Gabriel Figueroa (in Spanish)

- LACMA and The Academy co-present a major U.S. exhibition highlighting the prolific career of Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa

- Gabriel Figueroa: A Cinematographer’s Luminous Art

- Gabriel Figueroa at IMDb.

- Histórico de nominados y ganadores al Ariel (in Spanish)