Glutathione peroxidase 1

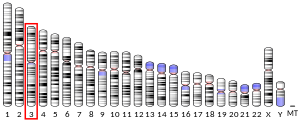

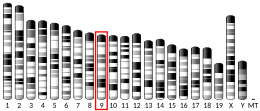

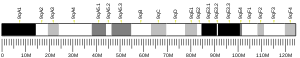

Glutathione peroxidase 1, also known as GPx1, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the GPX1 gene on chromosome 3.[5] This gene encodes a member of the glutathione peroxidase family. Glutathione peroxidase functions in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide, and is one of the most important antioxidant enzymes in humans.[6]

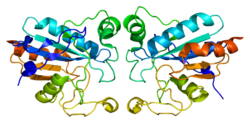

Structure

[edit]This gene encodes a member of the glutathione peroxidase family, consisting of eight known glutathione peroxidases (GPx1-8) in humans. Mammalian Gpx1 (this gene), Gpx2, Gpx3, and Gpx4 have been shown to be selenium-containing enzymes, whereas Gpx6 is a selenoprotein in humans with cysteine-containing homologues in rodents.[6][7][8] In selenoproteins, the 21st amino acid selenocysteine is inserted in the nascent polypeptide chain during the process of translational recoding of the UGA stop codon.[6][9] In addition to the UGA-codon, a cis-acting element in the mRNA, called SECIS, binds SBP2 to recruit other proteins, such as eukaryotic elongation factor selenocysteine-tRNA specific, to form the complex responsible for the recoding process.[8]

The protein encoded by this gene forms a homotetramer structure. As with other glutathione peroxidases, GPx1 has a conserved catalytic tetrad composed of Sec or Cys, Gln, Trp, and Asn, where the Sec is surrounded by four arginines (R 57, 103, 184, 185; bovine numbering) and a lysine of an adjacent subunit (K 91'). These 5 residues bind glutathione (GSH) and are only present in GPx1.[7]

Two alternatively spliced transcript variants encoding distinct isoforms have been found for this gene.[6]

Glutathione peroxidase 1 is characterized in a polyalanine sequence polymorphism in the N-terminal region, which includes three alleles with five, six or seven alanine (Ala) repeats in this sequence. The allele with five Ala repeats is significantly associated with breast cancer risk.[6]

Function

[edit]GPX1 is ubiquitously expressed in many tissues, where it protects cells from oxidative stress.[7][8] Within cells, it localizes to the cytoplasm and mitochondria.[7] As a glutathione peroxidase, GPx1 functions in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide, specifically by catalyzing the reduction of hydrogen peroxide to water. The glutathione peroxidase also catalyzes the reduction of other organic hydroperoxides, such as lipid peroxides, to the corresponding alcohols.[6][7][10] GPx1 typically uses glutathione (GSH) as the reductant, but when glutathione synthetase (GSS) is, as in brain mitochondria, γ-glutamylcysteine can serve as the reductant instead.[clarification needed][7] The protein encoded by this gene protects from CD95-induced apoptosis in cultured breast cancer cells and inhibits 5-lipoxygenase in blood cells, and its overexpression delays endothelial cell death and increases resistance to toxic challenges, especially oxidative stress.[8][10][11][12] This protein is one of only a few proteins known in higher vertebrates to contain selenocysteine, which occurs at the active site of glutathione peroxidase and is coded by the nonsense (stop) codon TGA.[6][8]

Animal studies

[edit]GPX1 helps to prevent cardiac dysfunction after ischemia-reperfusion injuries. Mitochondrial ROS production and oxidative mtDNA damage is increased during reoxygenation in the GPX1 knockout mice, in addition to structural abnormalities in cardiac mitochondria and myocytes, suggesting GPX1 may play an important role in protecting cardiac mitochondria from reoxygenation damage in vivo.[13]

In GPX1 (-/-) mice, oxidant formation is increased, endothelial NO synthase is deregulated, and adhesion of leukocytes to cultured endothelial cells is increased. Experimental GPX1 deficiency amplifies certain aspects of aging, namely endothelial dysfunction, vascular remodeling, and invasion of leukocytes in cardiovascular tissue.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]The GPx1 allele with five Ala repeats is significantly associated with breast cancer risk.[6]

Kocabasoglu, et al., sought to investigate connections between oxidative stress genes, including GPX1, and Panic Disorder, an anxiety disorder characterized by random and unexpected attacks of intense fear. Although the GPX1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, in general, did not significantly correlate with panic disorder risk, the study found a plausible association of the C allele of the GPX1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, found to be more frequent in the female cohort, with PD development.[15]

Ergen and colleagues analyzed gene expression of oxidative stress genes, specifically GPX1, in colorectal tumors in comparison to healthy colorectal tissues. ELISA was utilized to quantify GPX1 protein expression levels in both tissue types, highlighting a 2-fold decrease in tumor tissue (p<0.05).[16]

In esophageal cancer, Chen and colleagues found that vitamin D, a known suppressor of GPX1 expression via the NF-κB signaling pathway, could help to decrease the proliferative, migratory, and invasive capabilities of esophageal cancer cells. Unlike in colorectal cancer, GPX1 expression in esophageal cancer cells is thought to drive aggressive growth and metastasis, but Vitamin D-mediated decrease in GPX1 prevents such growth.[17]

In a study looking at gene polymorphisms of GPX1 and other oxidative stress genes in relation to prevalence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Banerjee, et al., found that while no association was found in expression of most GPX1 polymorphisms and risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, having the C allele of GPX1 led to a 1.362 times higher risk of the disease, highlighting the importance of finding individuals in the population with this gene variant to help treat them early on.[18]

Recent work by Alan M. Diamond and colleagues has shown that allelic variations of GPX1, like the codon 198 polymorphism that results in leucine or proline and an increase in alanine repeat codons, can result in different localization levels in MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells. For instance, the allele expressing the leucine-198 polymorphism and 7 alanine repeats generates GPX-1 localization that is disproportionately in the cytoplasm as compared to other allelic variants. To further understand the effects of these variants on GPX-1 function, mutant GPX-1 with mitochondrial localization sequences were generated and the GPX-1 infused cells were analyzed for their response to oxidative stress, energy metabolism and cancer-associated signaling molecules. Ultimately, GPX-1 variants heavily influenced cellular biology, suggesting that different GPX-1 variants affect cancer risk differently.[19]

An analysis of GPX1 expression in oligodendrocytes from patients with major depressive disorder and control patients showed that GPX1 levels were significantly decreased in patients with the disorder, but not in their astrocytes. Shortening of telomeres and decreased expression of telomerase were also evident in these oligodendrocytes, but not in the astrocytes in these patients. This suggests that decreased oxidative stress protection, as observed by decreased GPX1 levels, and decreased telomerase expression may help give rise to telomere shortening in patients with MDD.[20]

Interactions

[edit]GPX1 has been shown to interact with ABL and GSH.[7][21]

A recently discovered suppressor for GPX1 is S-adenosylhomocysteine, which when accumulated in endothelial cells can cause tRNA(Sec) hypomethylation, reducing the expression of GPX1 and other selenoproteins. The decreased GPX-1 expression can then lead to inflammatory activating of endothelial cells, helping give rise to a proatherogenic endothelial phenotype.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000233276 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000063856 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Kiss C, Li J, Szeles A, Gizatullin RZ, Kashuba VI, Lushnikova T, Protopopov AI, Kelve M, Kiss H, Kholodnyuk ID, Imreh S, Klein G, Zabarovsky ER (Jun 1998). "Assignment of the ARHA and GPX1 genes to human chromosome bands 3p21.3 by in situ hybridization and with somatic cell hybrids". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 79 (3–4): 228–30. doi:10.1159/000134729. PMID 9605859.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Entrez Gene: GPX1 glutathione peroxidase 1".

- ^ a b c d e f g Brigelius-Flohé R, Maiorino M (May 2013). "Glutathione peroxidases". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1830 (5): 3289–303. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.020. hdl:11577/2548683. PMID 23201771.

- ^ a b c d e Higashi Y, Pandey A, Goodwin B, Delafontaine P (Mar 2013). "Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates glutathione peroxidase expression and activity in vascular endothelial cells: Implications for atheroprotective actions of insulin-like growth factor-1". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1832 (3): 391–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.005. PMC 3557755. PMID 23261989.

- ^ Hubert N, Walczak R, Sturchler C, Myslinski E, Schuster C, Westhof E, Carbon P, Krol A (1996). "RNAs mediating cotranslational insertion of selenocysteine in eukaryotic selenoproteins". Biochimie. 78 (7): 590–6. doi:10.1016/s0300-9084(96)80005-8. PMID 8955902.

- ^ a b Tan SM, Stefanovic N, Tan G, Wilkinson-Berka JL, de Haan JB (Jan 2013). "Lack of the antioxidant glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1) exacerbates retinopathy of prematurity in mice". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 54 (1): 555–62. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-10685. PMID 23287791.

- ^ Gouaze V, Andrieu-Abadie N, Cuvillier O, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Frisach MF, Mirault ME, Levade T (Nov 2002). "Glutathione peroxidase-1 protects from CD95-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (45): 42867–74. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203067200. PMID 12221075.

- ^ Straif D, Werz O, Kellner R, Bahr U, Steinhilber D (Jul 2000). "Glutathione peroxidase-1 but not -4 is involved in the regulation of cellular 5-lipoxygenase activity in monocytic cells". The Biochemical Journal. 349 (Pt 2): 455–61. doi:10.1042/bj3490455. PMC 1221168. PMID 10880344.

- ^ Thu VT, Kim HK, Ha SH, Yoo JY, Park WS, Kim N, Oh GT, Han J (Jun 2010). "Glutathione peroxidase 1 protects mitochondria against hypoxia/reoxygenation damage in mouse hearts". Pflügers Archiv. 460 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1007/s00424-010-0811-7. PMID 20306076. S2CID 2922452.

- ^ Oelze M, Kröller-Schön S, Steven S, Lubos E, Doppler C, Hausding M, Tobias S, Brochhausen C, Li H, Torzewski M, Wenzel P, Bachschmid M, Lackner KJ, Schulz E, Münzel T, Daiber A (Feb 2014). "Glutathione peroxidase-1 deficiency potentiates dysregulatory modifications of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vascular dysfunction in aging". Hypertension. 63 (2): 390–6. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.01602. PMID 24296279.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Cengiz M, Bayoglu B, Alansal NO, Cengiz S, Dirican A, Kocabasoglu N (Mar 2015). "Pro198Leu polymorphism in the oxidative stress gene, glutathione peroxidase-1, is associated with a gender-specific risk for panic disorder". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 19 (3): 201–207. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1016973. PMID 25666858. S2CID 41231004.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Nalkiran I, Turan S, Arikan S, Kahraman ÖT, Acar L, Yaylim I, Ergen A (Jan 2015). "Determination of gene expression and serum levels of MnSOD and GPX1 in colorectal cancer". Anticancer Research. 35 (1): 255–9. PMID 25550558.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Gan X, Chen B, Shen Z, Liu Y, Li H, Xie X, Xu X, Li H, Huang Z, Chen J (2014). "High GPX1 expression promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invasion, migration, proliferation and cisplatin-resistance but can be reduced by vitamin D". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 7 (9): 2530–40. PMC 4211756. PMID 25356106.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Vats P, Sagar N, Singh TP, Banerjee M (Jan 2015). "Association of Superoxide dismutases (SOD1 and SOD2) and Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1) gene polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Free Radical Research. 49 (1): 17–24. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.971782. PMID 25283363. S2CID 21960657.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Bera S, Weinberg F, Ekoue DN, Ansenberger-Fricano K, Mao M, Bonini MG, Diamond AM (Sep 2014). "Natural allelic variations in glutathione peroxidase-1 affect its subcellular localization and function". Cancer Research. 74 (18): 5118–26. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-14-0660. PMC 4167490. PMID 25047527.

- ^ [unreliable medical source] Szebeni A, Szebeni K, DiPeri T, Chandley MJ, Crawford JD, Stockmeier CA, Ordway GA (Oct 2014). "Shortened telomere length in white matter oligodendrocytes in major depression: potential role of oxidative stress". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (10): 1579–89. doi:10.1017/s1461145714000698. PMID 24967945.

- ^ Cao C, Leng Y, Huang W, Liu X, Kufe D (Oct 2003). "Glutathione peroxidase 1 is regulated by the c-Abl and Arg tyrosine kinases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (41): 39609–14. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305770200. PMID 12893824.

- ^ Barroso M, Florindo C, Kalwa H, Silva Z, Turanov AA, Carlson BA, de Almeida IT, Blom HJ, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL, Michel T, Castro R, Loscalzo J, Handy DE (May 2014). "Inhibition of cellular methyltransferases promotes endothelial cell activation by suppressing glutathione peroxidase 1 protein expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (22): 15350–62. doi:10.1074/jbc.m114.549782. PMC 4140892. PMID 24719327.

Further reading

[edit]- Moscow JA, Morrow CS, He R, Mullenbach GT, Cowan KH (Mar 1992). "Structure and function of the 5'-flanking sequence of the human cytosolic selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase gene (hgpx1)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (9): 5949–58. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42647-6. PMID 1556108.

- Chada S, Le Beau MM, Casey L, Newburger PE (Feb 1990). "Isolation and chromosomal localization of the human glutathione peroxidase gene". Genomics. 6 (2): 268–71. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(90)90566-D. PMID 2307470.

- Mullenbach GT, Tabrizi A, Irvine BD, Bell GI, Hallewell RA (Jul 1987). "Sequence of a cDNA coding for human glutathione peroxidase confirms TGA encodes active site selenocysteine". Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (13): 5484. doi:10.1093/nar/15.13.5484. PMC 305979. PMID 2955287.

- Mullenbach GT, Tabrizi A, Irvine BD, Bell GI, Tainer JA, Hallewell RA (Sep 1988). "Selenocysteine's mechanism of incorporation and evolution revealed in cDNAs of three glutathione peroxidases". Protein Engineering. 2 (3): 239–46. doi:10.1093/protein/2.3.239. PMID 2976939.

- Sukenaga Y, Ishida K, Takeda T, Takagi K (Sep 1987). "cDNA sequence coding for human glutathione peroxidase". Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (17): 7178. doi:10.1093/nar/15.17.7178. PMC 306203. PMID 3658677.

- Ishida K, Morino T, Takagi K, Sukenaga Y (Dec 1987). "Nucleotide sequence of a human gene for glutathione peroxidase". Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (23): 10051. doi:10.1093/nar/15.23.10051. PMC 306556. PMID 3697069.

- Moscow JA, Schmidt L, Ingram DT, Gnarra J, Johnson B, Cowan KH (Dec 1994). "Loss of heterozygosity of the human cytosolic glutathione peroxidase I gene in lung cancer". Carcinogenesis. 15 (12): 2769–73. doi:10.1093/carcin/15.12.2769. PMID 8001233.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (Jan 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Chu FF, Doroshow JH, Esworthy RS (Feb 1993). "Expression, characterization, and tissue distribution of a new cellular selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase, GSHPx-GI". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (4): 2571–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53812-6. PMID 8428933.

- Esworthy RS, Ho YS, Chu FF (Apr 1997). "The Gpx1 gene encodes mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase in the mouse liver". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 340 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.9901. PMID 9126277.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (Oct 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Opalenik SR, Ding Q, Mallery SR, Thompson JA (Mar 1998). "Glutathione depletion associated with the HIV-1 TAT protein mediates the extracellular appearance of acidic fibroblast growth factor". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 351 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.0566. PMID 9501919.

- Forsberg L, de Faire U, Morgenstern R (1999). "Low yield of polymorphisms from EST blast searching: analysis of genes related to oxidative stress and verification of the P197L polymorphism in GPX1". Human Mutation. 13 (4): 294–300. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:4<294::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 10220143. S2CID 23075151.

- Choi J, Liu RM, Kundu RK, Sangiorgi F, Wu W, Maxson R, Forman HJ (Feb 2000). "Molecular mechanism of decreased glutathione content in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-transgenic mice". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (5): 3693–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.5.3693. PMID 10652368.

- Legault J, Carrier C, Petrov P, Renard P, Remacle J, Mirault ME (Jun 2000). "Mitochondrial GPx1 decreases induced but not basal oxidative damage to mtDNA in T47D cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 272 (2): 416–22. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.2800. PMID 10833429.

- Straif D, Werz O, Kellner R, Bahr U, Steinhilber D (Jul 2000). "Glutathione peroxidase-1 but not -4 is involved in the regulation of cellular 5-lipoxygenase activity in monocytic cells". The Biochemical Journal. 349 (Pt 2): 455–61. doi:10.1042/bj3490455. PMC 1221168. PMID 10880344.

- Richard MJ, Guiraud P, Didier C, Seve M, Flores SC, Favier A (Feb 2001). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein impairs selenoglutathione peroxidase expression and activity by a mechanism independent of cellular selenium uptake: consequences on cellular resistance to UV-A radiation". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 386 (2): 213–20. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.2197. PMID 11368344.

- Ishibashi N, Prokopenko O, Reuhl KR, Mirochnitchenko O (Feb 2002). "Inflammatory response and glutathione peroxidase in a model of stroke". Journal of Immunology. 168 (4): 1926–33. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1926. PMID 11823528.

- Gouaze V, Andrieu-Abadie N, Cuvillier O, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Frisach MF, Mirault ME, Levade T (Nov 2002). "Glutathione peroxidase-1 protects from CD95-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (45): 42867–74. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203067200. PMID 12221075.