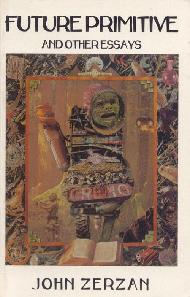

Future Primitive and Other Essays

| |

| Author | John Zerzan |

|---|---|

| Subject | Anarcho-primitivism |

| Genre | Anthropology, political economy |

| Publisher | Autonomedia, Anarchy: a Journal of Desire Armed |

Publication date | December 1, 1994 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Paperback |

| Pages | 192 pages |

| ISBN | 1-57027-000-7 |

| OCLC | 30630861 |

| Preceded by | Elements of Refusal |

| Followed by | Running on Emptiness |

Future Primitive and Other Essays is a collection of essays by anarcho-primitivist philosopher John Zerzan published by Autonomedia in 1994. The book became the subject of increasing interest after Zerzan and his beliefs rose to fame in the aftermath of the trial of fellow thinker Theodore Kaczynski and the 1999 anti-WTO protests in Seattle.[1] It was republished in 1996 by Semiotext(e), and has since been translated into French (1998), Turkish (2000), Spanish (2001), and Catalan (2002). As is the case with Zerzan's previous collection of essays, Elements of Refusal, Future Primitive is regarded by Anarcho-Primitivists and technophobes as an underground classic.[2]

Thesis

[edit]Future Primitive is an unequivocal assertion of the superiority of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[3] Zerzan rejects the thesis that time and technology are neutral scientific realities, arguing instead that they are carefully constructed means of enslaving people.[4] He cites as examples the computer and the Internet, which he maintains have an atomizing effect on society, creating novel divisions of labour, demanding ever increasing efficiency and portions of leisure time.[4] Life prior to domestication and agriculture, Zerzan argues, was predominantly one of "leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality and health".[5] In the Paleolithic era, as The Wall Street Journal summarized Zerzan's thesis, "people roamed free, lived off the land and knew little or nothing of private property, government, money, war, even sexism. In the wild, the shackles of civilization weren't necessary, as people were instinctively munificent and kind, the primitivist argument goes."[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Campbell, Duncan (April 18, 2001). "Anarchy in the United States". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ^ Noble, Kenneth B. (May 7, 1995). "Prominent Anarchist Finds Unsought Ally in Serial Bomber". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ^ Gowdy, John (1998). Limited Wants, Unlimited Means. Washington: Island Press. p. 220. ISBN 1-55963-555-X.

- ^ a b Veseth, Michael (2002). The New York Times Twentieth Century in Review: the Rise of the Global Economy. New York: Routledge. pp. 515. ISBN 1-57958-369-5.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (1995). Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism. Stirling: AK Press. p. 39. ISBN 1-873176-83-X.

- ^ Waldman, Peter (December 6, 1999). "An Anarchist Looks to Provide Logic To Coterie Leading WTO Vandalism". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Alt URL

External links

[edit]- Future Primitive and Other Essays (PDF) – Libcom.org