Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya

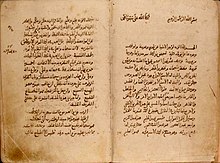

Opening pages of the Konya Manuscript of the Meccan Revelations, handwritten by Ibn Arabi. | |

| Original title | الفُتُوحَات المكّيّة |

|---|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Ibn 'Arabi |

|---|

The Meccan Revelations (Arabic: كِتَابُ الفُتُوحَاتِ المَكِّيَّة, romanized: Kitâb Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya)[1] is the major work of the philosopher and Sufi[2] Ibn Arabi, written between 1203 and 1240.

The Andalusi thinker exposes his spiritual journey, his theology, his metaphysics and his mysticism, using sometimes prose, sometimes poetry. The book contains autobiographical elements: encounters, events, and spiritual illuminations.

History

[edit]Ibn Arabi wrote two versions of al-Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah, his magnum opus.[3] He completed the first in the year 629 of the Hijra and worked on the second version between the years 632 and 636 of the Hijra.[3] The second version, called the Konya Manuscript (مخطوط قونية), exists in manuscripts in Ibn Arabi's own hand, with the exception of volume nine.[3] These manuscripts, once part of the waqf of Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, are known as the "Konya" manuscripts and they are now kept in Istanbul (Evkaf Muzesi 1845-1881).[3]

It was first published by the Bulaq Press in four volumes in Dhū al-Ḥijja 1269/1853.[3] The Bulaq Press published a second edition in 1293/1876, also in four volumes.[3] The third edition, the standard Cairo edition, printed 1329/1911, also published by the Bulaq Press in four volumes, is based on Ibn Arabi's second version completed in 636 H, thanks to the research of Emir Abdelkader.[3]

Structure

[edit]The Revelations is a book of 37 volumes, divided into 560 chapters.[4]

Content

[edit]

The book takes its title from the holy city of Mecca, to which Ibn Arabi travelled on pilgrimage in 1202, and in which he received a number of revelations of divine origin.

In the Illuminations Ibn Arabi develops a theory of the imagination and the imaginary world explained by Henry Corbin.[5] There is also a psychological and religious description of the effects of Allah's Love (in both the subjective and objective sense of expression).

According to Michel Chodkiewicz, this book occupies a particularly important place in Ibn Arabi's work because it represents "the ultimate state of his teaching in its most complete form".[6]

Aside from Ibn Taymiyyah, his many critics have included the historian Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Sufi Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624), members of the Wahhabi cult of Saudi Arabia and beyond, and an array of modern Muslim revivalists and modernists. Controversy over his teachings flared again in 1979 when the Egyptian parliament attempted to ban the republication of the print edition of The Meccan Revelations. The attempt failed due to public outcry.[7]

Women, poetry, religious love

[edit]Women are prominently featured in the book, particularly in Chapter 178 on love. Ibn Arabi is initiated into religious experience by a spiritual woman called Nizham, a young Persian woman whose name means "Harmony". He quotes the poems of the writer Rabia of Basra, who according to him is "the most prestigious interpreter" of love.[8] Ibn Arabi also recounts his encounter and service to mystic Fatima bint al-Muthanna, with whom he recites Al Fātiḥah (the first surah of the Quran) and whose degree of spiritual elevation he admires.[9]

Legacy

[edit]The Illuminations are a classic of Sufism, theology and Islamic philosophy. They influenced the "Spiritual Writings" of the emir Abd el-Kader, who published the book in 1857, and perhaps Dante.[10] Henry Corbin compared Dante's Béatrice, which leads the poet to paradise in the Divine Comedy and awakens him to love in the Vita Nuova, to Ibn Arabi's Nizhâm, a mystical woman who initiates the Andalusian philosopher to the experience of God's love.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Introduction to The Meccan Revelations on Ibnarabisociety

- ^ Read Secret Practices of the Sufi Freemasons Online by Baron Rudolf von Sebottendorff | Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g "al-Futuhat al-Makiyya Printed Editions". Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Constant Hamès, Ibn Arabî, Les Illuminations de La Mecque (compte rendu), Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 1990, Vol. 72, N°1, p. 266-267.

- ^ Henry Corbin, L'imagination créatrice dans le soufisme d'Ibn Arabi.

- ^ Michel Chodkiewicz (1997). Avant-propos in Les Illuminations de La Mecque (in French). Paris: Albin Michel. p. 10..

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ^ Treaty of Love, p. 247.

- ^ Traité de l'amour, p. 188-190.

- ^ The hypothesis of Ibn Arabi's influence on Dante comes from Miguel Asin Palacios See « After Ibn Arabi ».

- ^ Florian Besson, "Ibn Arabî", Les Clés du Moyen Orient, 1 April 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Partial editions

- Anthology: Les Illuminations de La Mecque, Paris, Éditions Albin Michel, 2008 (1988), Spiritualités vivantes , trans. Michel Chodkiewicz.

- Anthology: Les Révélations de La Mecque, Paris, Entrelacs, 2009, trans. Abdallah Penot.

- Two chapters in: Par-delà le miroir, Paris, Entrelacs, 2012, "Hikma", trans. Abdallah Penot.

- Chapters 61 to 65: De la mort à la résurrection, Paris, Albouraq, 2009, trans. Maurice Gloton.

- Chapter 167: L'Alchimie du Bonheur parfait, Paris, Berg International, 1981, trans. Stéphane Ruspoli.

- Chapitre 178 : Traité de l'amour, Paris, Albin Michel, 1986, "Spiritualités vivantes", trans. Maurice Gloton.

- Studies

- Claude Addas, Expérience et doctrine de l'amour chez Ibn Arabî, in Mystique musulmane (collective work), Paris, Cariscript, 2002.

- Henry Corbin, L'imagination créatrice dans le soufisme d'Ibn Arabi, Paris, Flammarion, 1958, reprint Flammarion-Aubier, 1993.

- George Grigore, Le concept d’amour chez Ibn 'Arabi, "Romano-Arabica", II, Bucharest: Center for Arab Studies. 2002; p. 119-134.