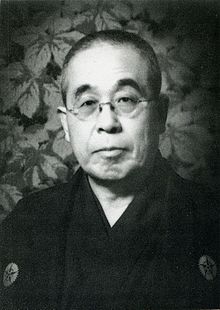

Fusanosuke Kuhara

Fusanosuke Kuhara 久原 房之助 | |

|---|---|

Fusanosuke Kuhara | |

| Born | 12 July 1869 |

| Died | 29 January 1965 (aged 95) |

| Occupation(s) | entrepreneur, politician, cabinet minister |

Fusanosuke Kuhara (久原 房之助, Kuhara Fusanosuke, 12 July 1869 – 29 January 1965) was an entrepreneur, politician and cabinet minister in the pre-war Empire of Japan.

Biography

[edit]Kuhara was born in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture into a family of sake brewers. His brother was the founder of Nippon Suisan Kaisha and his uncle Fujita Densaburō was the founder of the Fujita zaibatsu. He studied in 1885 at the Tokyo Commercial School (the predecessor of Hitotsubashi University) and went on to graduate from Keio University. After graduation, he joined the Morimura-gumi, but on the recommendation of ex-Chōshū politicians Inoue Kaoru, he joined his uncle’s company, the Fujita-gumi (current Dowa Holdings), and in 1891 was assigned management of the Kosaka mine in Kosaka, Akita, one of the largest lead, copper and zinc mines in Japan. He introduced new technologies and made the mine very profitable.

In 1903, he left the Fujita-gumi, and acquired the Akazawa Copper Mine in Ibaraki Prefecture in 1905, renaming it the Hitachi Copper Mine. He established Hitachi Seisakusho in 1910, merging his operations into Kuhara Kōgyō in 1912. The mine became the second largest producer of copper in Japan in 1914 through mechanization and improved production techniques.

During World War I, Kuhara expanded his operations into a vast array of enterprises, ranging from shipbuilding to fertilizer production, petrochemical, life insurance, trading and shipping, creating the Kuhara zaibatsu. However, the overextended company experienced severe financial difficulties in the post-war depression, and Kuhara turned to his brother-in-law, Yoshisuke Aikawa, who created a holding company called Nihon Sangyō, or Nissan for short. Kuhara went on to a career in politics, forging ties with future Prime Minister Giichi Tanaka and other political and military leaders, which Aikawa would later use to his advantage.[1]

In 1928, Kuhara was elected to the lower house of the Diet of Japan as a member of the Rikken Seiyūkai from the Yamaguchi 1st Electoral District, and was made Minister of Communications the same year in the Tanaka administration[2]

He served as secretary-general of the Rikken Seiyūkai in 1931 under Inukai Tsuyoshi. Politically, Kuhara supported a hard-line approach against China, and was a vocal supporter of a constitutional reform intended to transform Japan into a one-party state. However, Kuhara was briefly arrested after the February 26 incident and forced to resign from the party after it was discovered that he had made a financial contribution to the rebels.[3]

After the Rikken Seiyūkai party split, Kuhara was invited back into politics by Ichirō Hatoyama, leading the faction opposed to Chikuhei Nakajima, and rising to the post of president of the party in 1939.[4]

In 1940, he presided over the absorption of the party into Fumimaro Konoe’s Taisei Yokusankai, thus fulfilling his ambition of creating a one-party state. Under the Hiranuma administration, he served as an advisor to the cabinet. He was one of the key organizers of the League of Diet Members Carry Through the Holy War.

After World War II, Kuhara was purged by the American occupation authorities. After the end of the occupation, he was elected to the post-war House of Representatives of Japan from the Yamaguchi 2nd Electoral District in the 1952 General Election. He played an important role in the restoration of Russo-Japanese relations and Sino-Japanese relations.

Kuhara died at his home in Shirokanedai, Minato, Tokyo in January 1965. His home is now the Happo-en, a hotel with a noted Japanese garden.

Residence and Bridge

[edit]

One of his residences, which was in Sumiyoshi village in Kobe〈now, near Sumiyoshi Station (JR West), to which it is said that he crossed his private bridge shown above on his private carriage with chauffeur from the main gate of his residence also shown above to go, and Nada High School〉had a hospital, electric power plant and the custom-made air-conditioning tunnel from Mount Rokkō for itself in the era without air conditioning. He was also running true locomotives in the garden for his children.[5][6]

References

[edit]- ^ Samuels, Rich Nation, Strong Army. p.102

- ^ Hunter, Janet (1984). Concise Dictionary of Modern Japanese History. University of California Press. p. 278. ISBN 0520045572.

- ^ Shillony, Ben-Ami (2007). Ben-Ami Shillony - Collected Writings. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-1134252305.

- ^ Itoh, Mayumi (2003). The Hatoyama Dynasty: Japanese Political Leadership Through the Generations. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 67. ISBN 1403981523.

- ^ …学校の川向かい、現在のオーキッドコート一帯に大邸宅を構えていた鉱山王・久原房之助… | 神戸の社会に尽くしたサムライ紳士 平生 釟三郎|今も神戸に生きる 平生釟三郎の精神 : 神戸っ子 KOBECCO(2018年5月号)〈"Mine King" Fusanosuke Kuhara who had mansion… (KOBECCO, May, 2018)〉

- ^ 財界の名士が次々邸宅 神戸に「日本一の富豪村」(神戸新聞NEXT)〈Prominent persons in Business Circle building residences in succession. The wealthiest village in Kobe (Kobe Shimbun NEXT)〉

External links

[edit]- 1869 births

- 1965 deaths

- People from Yamaguchi Prefecture

- Government ministers of Japan

- Japanese mining businesspeople

- Japanese prisoners and detainees

- Keio University alumni

- Hitotsubashi University alumni

- Imperial Rule Assistance Association politicians

- Rikken Seiyūkai politicians

- Members of the House of Representatives (Empire of Japan)

- Prisoners and detainees of Japan