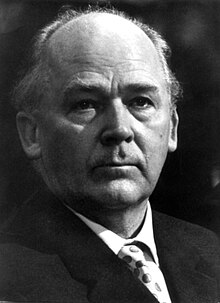

Fritz Strassmann

Fritz Strassmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann 22 February 1902 |

| Died | 22 April 1980 (aged 78) |

| Alma mater | Technical University of Hannover (PhD) |

| Known for | Discovery of nuclear fission |

| Awards | Enrico Fermi Award (1966) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Kaiser Wilhelm Institute University of Mainz |

| Doctoral advisor | Hermann Braune |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

| By country |

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (German: [fʁɪt͡s ˈʃtʁasˌman] ⓘ; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key piece of evidence necessary to identify the previously unknown phenomenon of nuclear fission, as was subsequently recognized and published by Lise Meitner and Robert Frisch. In their second publication on nuclear fission in February 1939, Strassmann and Hahn predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

Personal life and education

[edit]Friedrich Wilhelm (Fritz) Strassmann was born in Boppard, Germany, to Richard Strassmann and Julie Strassmann (née Bernsmann). He was the youngest of nine children. Growing up in Düsseldorf, he developed an interest in chemistry at a young age and conducted chemistry experiments in his parents' home. His family was of modest means, and his father died at a young age, worsening the family's financial situation. Financial considerations limited Strassmann's initial choices of where to pursue his higher education and what subjects they should be.[1][2]

Strassmann began his formal chemistry studies in 1920 at the Technical University of Hannover, supporting himself financially by working as a tutor for other students. He received a diploma in chemical engineering in 1924, and his PhD in physical chemistry in 1929.[1][2] His doctoral research was on the solubility and reactivity of iodine in carbonic acid in the gas phase, which gave him experience in analytical chemistry. Strassmann's doctoral advisor was Hermann Braune.[1]

Subsequently, Strassmann received a partial scholarship to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin-Dahlem, beginning in 1929.[3] There he studied radiochemistry with Otto Hahn, who arranged twice for his scholarship to be renewed. When his scholarship expired in September 1932, Strassmann continued to work as a research student in Hahn's laboratory, without a stipend but without having to pay tuition.[1]

On 20 July 1937 Strassmann married Maria Heckter, also a chemist. Strassmann was a self-taught violinist. He met Maria Heckter through a group of young musicians that they both belonged to. They had a son, Martin.[1]

Maria died of cancer in 1956. In 1959, Strassmann married journalist Irmgard Hartmann. He had known Hartmann for many years, as she was a member of the same group of young musicians that Strassmann and his wife Maria had belonged to.[1]

Activities during Nazi rule

[edit]In 1933 Strassmann resigned from the Society of German Chemists when it became part of a Nazi-controlled public corporation. He was blacklisted by the Nazi regime. As a result, he could not work in the chemical industry nor could he receive his habilitation, as required to be an independent researcher in Germany at the time.[1][4] Lise Meitner encouraged Otto Hahn to find an assistantship for Strassmann at half pay, and he eventually became a special assistant to Meitner and Hahn.[1] Strassmann considered himself fortunate, for "despite my affinity for chemistry, I value my personal freedom so highly that to preserve it I would break stones for a living."[4]

Strassman's wife Maria supported his refusal to join the Nazi Party.[1][4] During World War II they concealed a Jewish woman, musician Andrea Wolfenstein, in their apartment for months, putting themselves and their three-year-old son at risk.[5][4] Strassmann continued his research in radiochemistry during World War II, although he did not work on weapons development. He disdained the Nazi regime and is reported to have said, "If my work would lead to Hitler having an atomic bomb I would kill myself."[6]

Discovery of nuclear fission

[edit]Hahn and Meitner made use of Strassmann's expertise in analytical chemistry in their investigations of the products resulting from bombarding uranium with neutrons. Of these three scientists, only Strassmann was able to remain focused on their joint experimental investigations. Meitner, being Jewish, was forced to leave Nazi Germany, and Hahn had extensive administrative duties.[1]

In 1937 and 1938, scientists Irène Joliot-Curie and Paul Savič reported results from their investigations on irradiating uranium with neutrons. They were unable to identify the substances that formed as a result of the uranium irradiation. Strassmann, with Hahn, was able to identify the element barium as a major end product in the neutron bombardment of uranium, through a decay chain. The result was surprising because of the large difference in atomic number of the two elements, uranium having atomic number 92 and barium having atomic number 56.[1]

In December 1938, Hahn and Strassmann sent a manuscript to Die Naturwissenschaften reporting the results of their experiments on detection of barium as a product of neutron bombardment of uranium.[9] Robert Frisch confirmed Strassman and Hahn's report experimentally on 13 January 1939.[10] Frisch and Meitner explained Strassman's and Hahn's findings as being from nuclear fission, which they named.[11] In 1944, Hahn received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission, although Fritz Strassmann had been acknowledged as an equal collaborator in the discovery.[12]

World War II

[edit]Working at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute from 1939 to 1946, Strassman contributed to research on the fission products of thorium, uranium, and neptunium. In this way, he contributed to the understanding of the radiochemistry of the actinide elements. He developed methods for the dating of the age of minerals and other inorganic substances based on the half-life of radioactive elements and the enrichment of decay products. Strassmann and Ernst Walling developed the rubidium-strontium method of radiometric dating in 1936 and 1937, and Strassmann continued this work in 1942 and 1943. His methods are known as emanation methods, and Strassmann's research in this area was fundamental to the field of geochronology.[1]

"Zur Folge nach der Entstehung des 2,3 Tage-Isotops des Elements 93 aus Uran" ["Following the formation of the 2.3-day isotope of element 93 from uranium"] G-151 (27 February 1942) by Hahn and Strassmann was published in Kernphysikalische Forschungsberichte [Research Reports in Nuclear Physics], an internal publication of the German Uranverein. Reports in this publication were classified as "Top Secret" and therefore had very limited distribution, and the authors were not allowed to keep copies. They were confiscated by the Allied Operation Alsos in 1945. In 1971, the reports were declassified and returned to Germany. They are available at the Karlsruhe Nuclear Research Center and the American Institute of Physics.[13][14]

On 15 February 1944 and again on 24 March 1944, the Institute suffered severe bombing damage. For this reason, the institute was temporarily relocated to Tailfingen (now Albstadt) in the Württemberg district, in a textile factory belonging to the Ludwig Haasis company.[15][16]

Post-war

[edit]Administrative responsibilities

[edit]In April 1945, Hahn and other German physicists were taken into custody as part of Operation Epsilon and interned at Farm Hall, Godmanchester, near Cambridge, England.[17] In Hahn's absence, Strassmann became director of the chemistry section of the institute.[15] Strassman became professor of inorganic chemistry and nuclear chemistry at the University of Mainz in 1946.[2]

The Institute consisted of two departments: Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Physics was Josef Mattauch's department, while Nuclear Chemistry was Strassmann's department. Mattauch was appointed director of the institute. Mattauch developed tuberculosis, and, in his absence, Strassman became acting director in 1948. As of 1949, the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute was renamed the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, and moved from Tailfingen to Mainz, Germany.[16] In 1950 Strassmann became the official director of the institute.[15][16] After Mattauch returned in 1951, there was considerable conflict over the allocation of resources to their respective departments.[1]

Renewed research

[edit]

In 1953, Strassmann gave up the directorship, choosing instead to focus on his research and scholarship at the University of Mainz. He succeeded in building up the department's capabilities, and he worked directly with students. Strassmann began these undertakings at the University of Mainz with a few scattered rooms and very little money. He negotiated with the university and with Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabriken (BASF) to fund an institute for the chemical sciences at the university with a focus on nuclear chemistry. He also lobbied the German federal government to fund a neutron generator, a nuclear reactor for research purposes, and a special institute for nuclear chemistry. Strassman's creation, the Institute for Nuclear Chemistry, officially opened on 3 April 1967.[2][1]

In 1957, Strassmann was one of the Göttinger Achtzehn (Göttingen eighteen), a group of leading nuclear researchers of the Federal Republic of Germany who wrote a manifesto (Göttinger Manifest, Göttinger Erklärung) opposing chancellor Konrad Adenauer and defense secretary Franz-Josef Strauß's plans to equip the Bundeswehr, Western Germany's army, with tactical nuclear weapons.[18]

Strassmann retired in 1970.[2][1] He died on 22 April 1980 in Mainz.[2]

Honors and recognition

[edit]In 1966, United States President Lyndon Johnson honored Hahn, Meitner and Strassmann with the Enrico Fermi Award.[19] The International Astronomical Union named an asteroid after him: 19136 Strassmann.[20]

In 1985, Fritz Strassmann was recognized by Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations (חסיד אמות העולם).[5]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Krafft, Fritz. "Strassmann, Friedrich Wilhelm (Fritz)". Encyclopedia.com / Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Friedlander, Gerhart; Herrmann, Günter (April 1981). "Fritz Strassmann". Physics Today. 34 (4): 84–86. Bibcode:1981PhT....34d..84F. doi:10.1063/1.2914536. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann". Science History Institute. June 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Sime, Ruth Lewin (1996). Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-520-08906-8. OCLC 32893857.

- ^ a b "Strassmann Fritz". The Righteous Among the Nations Database. Yad Vashem. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Fritz Strassmann". spartacus-educational.com. Spartacus Educational Publishers. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ "Originalgeräte zur Entdeckung der Kernspaltung, 'Hahn-Meitner-Straßmann-Tisch'" [Original equipment for the discovery of nuclear fission, 'Hahn-Meitner-Straßmann table'] (in German). Deutsches Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Sime, Ruth Lewin (15 June 2010). "An Inconvenient History: The Nuclear-Fission Display in the Deutsches Museum". Physics in Perspective. 12 (2): 206–210. Bibcode:2010PhP....12..190S. doi:10.1007/s00016-009-0013-x. ISSN 1422-6944. S2CID 120584702.

- ^ Hahn, O.; Strassmann, F. "Über den Nachweis und das Verhalten der bei der Bestrahlung des Urans mittels Neutronen entstehenden Erdalkalimetalle" [On the detection and characteristics of the alkaline earth metals formed by irradiation of uranium with neutrons]. Naturwissenschaften (in German). 27 (1): 11–15.

- ^ Frisch, O. R. "Physical Evidence for the Division of Heavy Nuclei under Neutron Bombardment". Nature. 143 (3, 616): 276–276. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Hitler and the Bomb". New York Times. 11 December 1988.

- ^ Bowden, Mary Ellen (1997). Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of the Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 76–80. ISBN 9780941901123.

- ^ Hentschel, Klaus; Hentschel, Ann M. (1996). Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources. Birkhäuser. p. XVI, XLVIII. ISBN 9783034802031., See Appendix E; entry for Kernphysikalische Forschungsberichte.

- ^ Walker, Mark (1993). German national socialism and the quest for nuclear power, 1939-1949. Cambridge University Press. pp. 268–274. ISBN 0-521-43804-7.

- ^ a b c "Chronik des Kaiser-Wilhelm- / Max-Planck-Instituts für Chemie" (PDF). Max-Planck-Instituts für Chemie. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Palme, Herbert (2018). "Cosmochemistry along the Rhine" (PDF). Geochemical Perspectives. 7 (1): 4–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Walker, Mark (1993). German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-521-36413-2. OCLC 722061969.

- ^ Castell, Lutz; Ischebeck, Otfried, eds. (2003). Time, Quantum and Information. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-3-662-10557-3. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Scientific and Technology Division, Library of Congress (1967). Astronautics and Aeronautics. Washington, D.C.: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 259.

- ^ "19136 Strassmann (1989 AZ6)". JPL Small-Body Database Browser. NASA. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Braune, H.; Strassmann, Fritz (1929). "Über die Löslichkeit von Jod in gasförmiger Kohlensäure". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (in German). 143A (1): 225–243. doi:10.1515/zpch-1929-14321.

- Krafft, Fritz (1981). Im Schatten der Sensation. Leben und Wirken von Fritz Strassmann (in German). Weinheim: Verlag Chemie. OCLC 7948505.

External links

[edit]- Otto Hahn, 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Fritz Strassmann – his activity to save Jews' lives during the Holocaust, at Yad Vashem website

- Enrico Fermi Award recipients

- 20th-century German chemists

- German Righteous Among the Nations

- Nuclear chemists

- Nuclear program of Nazi Germany

- Otto Hahn

- Scientists from the Rhine Province

- Academic staff of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

- 1902 births

- 1980 deaths

- Rare earth scientists

- German people of World War II

- Max Planck Institute directors