French battleship Strasbourg

Strasbourg in port

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Strasbourg |

| Namesake | City of Strasbourg |

| Ordered | 16 July 1934 |

| Builder | Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire |

| Laid down | November 1934 |

| Launched | December 1936 |

| Commissioned | 15 September 1938 |

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Dunkerque-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 214.5 m (703 ft 9 in) (loa) |

| Beam | 31.08 m (102 ft) |

| Draft | 8.7 m (28 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 Shafts; 4 geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph) |

| Range | 13,900 km (7,500 nmi; 8,600 mi) |

| Crew | 1,381–1,431 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 2 floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities | 1 catapult |

Strasbourg was the second and final member of the Dunkerque class of fast battleships built for the French Navy in the 1930s. She and her sister ship Dunkerque were designed to defeat the German Deutschland class of heavy cruisers that had been laid down beginning in the late 1920s, and as such were equipped with a battery of eight 330 mm (13 in) guns to counter the six 280 mm (11 in) guns of the Deutschlands. Strasbourg was laid down in November 1934, was launched in December 1936, and was commissioned in September 1938 as the international situation in Europe was steadily deteriorating due to Nazi Germany's increasingly aggressive behavior.

Strasbourg was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet upon entering service; her only significant peacetime activities consisted of visits to Portugal in May 1939 and a tour of Great Britain in May and June that year. She spent the next two months training with other units of the fleet and in September, France and Britain declared war on Germany over its invasion of Poland, starting World War II. The two Dunkerque-class ships formed the core of the Force de Raid (Raiding Force), tasked with protecting Allied merchant shipping in the central Atlantic. The unit was quickly divided into two groups, with Strasbourg and other units being detached as Force X, based in Dakar. With an increasingly belligerent Italy threatening to enter the war in April 1940, Force X was recalled to the Mediterranean to act as a deterrent, though the defeat of French forces in the Battle of France rendered the situation moot.

The armistice specified that Strasbourg and the rest of the French fleet would be demilitarized, and she and several other battleships were stationed in Mers-el-Kébir at the time. Mistakenly under the impression that the Germans sought to seize the ships, the British Force H was sent to either force the ships to continue fighting or to destroy them. When the French refused the ultimatum, the British opened fire, but Strasbourg evaded the British and escaped to Toulon. There, she served as the flagship of the newly established Forces de haute mer until the Germans attempted to seize the fleet during Case Anton, leading to its destruction in the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon in November 1942. The wreck was seized by the Italians, who raised Strasbourg and then started dismantling the ship, and was later taken by the Germans. The vessel was bombed and sunk a second time by American bombers in August 1944, and was sold for scrap in 1955.

Development

[edit]

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty attempting to produce a satisfactory design which would allow several ships to be built within the 70,000-ton limit allowed by the treaty.[1] Initially, the French sought a reply to the Italian Trento-class cruisers of 1925, but all proposals were rejected. A 17,500-ton cruiser, which could have handled the Trentos, was inadequate against the old Italian battleships, however, and the 37,000-ton battlecruiser concepts were prohibitively expensive and would jeopardize further naval limitation talks. These attempts were followed by an intermediate design for a 23,690-ton protected cruiser in 1929; it was armed with 305 mm (12 in) guns, armored against 203 mm (8 in) guns, and had a speed of 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph). Visually, it bore a profile strikingly similar to the final Dunkerque-class design.[2][3]

The German Deutschland-class cruisers became the new focus for French naval architects in 1929. The design had to respect the 1930 London Naval Treaty, which limited the French to two 23,333-ton ships until 1936. Drawing upon previous work, the French developed a 23,333-ton design armed with 305 mm guns, armored against the German cruisers' 280 mm (11 in) guns, and with a speed of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). As with the final Dunkerque-class design, the main artillery was concentrated entirely forward. The design was rejected by the French parliament in July 1931 and sent back for revision. The final revision grew to 26,500 tons; the 305 mm guns were replaced by 330 mm (13 in) /50 Modèle 1931 guns, the armor was slightly improved, and the speed slightly decreased.[4][5] Parliamentary approval was granted for the first member of the class in early 1932,[6] and Strasbourg was ordered on 16 July 1934 with the design unchanged but with greater armor thicknesses and increased weight.[5]

Characteristics

[edit]

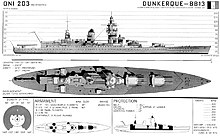

Strasbourg displaced 27,700 long tons (28,100 t) standard and 35,500 long tons (36,100 t) fully loaded, with an overall length of 214.5 m (703 ft 9 in), a beam of 31.08 m (102 ft) and a maximum draft of 8.7 m (28 ft 7 in). She was powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and six oil-fired Indret boilers, which developed a total of 112,500 shaft horsepower (83,900 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph).[7] Her crew numbered between 1,381 and 1,431 officers and men.[Note 1] The ship carried a pair of spotter aircraft on the fantail, and the aircraft facilities consisted of a steam catapult and a crane to handle the floatplanes.[7]

She was armed with eight 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns arranged in two quadruple gun turrets, both of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward of the superstructure. Her secondary armament consisted of sixteen 130 mm (5.1 in) /45 dual-purpose guns; these were mounted in three quadruple and two twin turrets. The quadruple turrets were placed on the stern, with one on the centerline on the superstructure and the other two on either side on the upper deck, and the twin turrets were located amidships, just forward of the funnel. Close range antiaircraft defense was provided by a battery of eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns in twin mounts and thirty-two 13.2 mm (0.52 in) guns in quadruple mounts.[7] The ship's belt armor was 283 mm (11.1 in) thick amidships, and the main battery turrets were protected by 360 mm (14.2 in) of armor plate on the faces, both thicker than installed in Dunkerque. The main armored deck was 127 mm (5 in) thick, and the conning tower had 270 mm (10.6 in) thick sides.[10]

Service history

[edit]Prewar service

[edit]Strasbourg was ordered on 16 July 1934 in response to the Italian Littorio-class battleships.[5] The keel for the ship was laid down in November 1934 in the No. 1 slipway of the civilian Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire shipyard in Saint-Nazaire. After her launching in December 1936, she was moored along the fitting-out quay, where her armament, propulsion system, and other equipment were installed. Strasbourg departed Saint-Nazaire on 15 June 1938, bound for Brest, France; while en route she conducted brief speed tests. The ship arrived on 16 June and departed again on 21 June to begin official acceptance trials. Modifications were done from 22 to 30 June, followed by more sea trials that continued into August. Gunnery trials were performed on 24–25 August off the island of Ushant, and the ship was formally commissioned on 15 September. That day, she was drydocked so that her propulsion system could be inspected after the trials. On 15 December, Strasbourg went to sea to resume working up for active service, including more gunnery testing. By this time, the international situation in Europe had begun to worsen as Nazi Germany began making increasingly hostile demands on its neighbors.[11]

On 24 April 1939, the ship was finally ready for active service, joining the Atlantic Fleet with her sister ship Dunkerque; the two ships were designated the 1st Battle Division. The ships received identification stripes on their funnels, one for Dunkerque as division leader, and two for Strasbourg.[12][13] Strasbourg joined Dunkerque on 1 May for the first time for a cruise to Lisbon, Portugal on 1 May, arriving there two days later for a celebration of the anniversary of Pedro Álvares Cabral's discovery of Brazil. The ships left Lisbon on 4 May and arrived in Brest three days later. There, they met a British squadron of warships that were visiting the port at the time. The two Dunkerque-class ships sortied on 23 May in company with the 4th Cruiser Division and three destroyer divisions for maneuvers held off the coast of Great Britain. Dunkerque and Strasbourg then visited a number of British ports, including Liverpool from 25 to 30 May, Oban from 31 May to 4 June, Staffa on 4 June, Loch Ewe from 5 to 7 June, Scapa Flow on 8 June, Rosyth from 9 to 14 June, before stopping in Le Havre, France from 16 to 20 June. The ships arrived back in Brest the next day. The squadron conducted more training off Brittany through July and into early August.[14]

World War II

[edit]

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the Gulf of Guinea in central Africa. To protect shipping from German commerce raiders, the French created the Force de Raid (Raiding Force), with Strasbourg and Dunkerque as its core. The group, which was under the command of Vice-amiral d'Escadre (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, also included three light cruisers and eight large destroyers, and was based in Brest. British observers informed the French Navy that the German "pocket battleships" of the Deutschland class had gone to sea in late August, bound for the Atlantic, and that contact with the vessels had been lost. On 2 September, the day after Germany invaded Poland, but before France and Britain declared war, the Force de Raid sortied from Brest to guard against a possible attack by the Deutschlands. Upon learning that the German ships had been spotted in the North Sea, Gensoul ordered his ships to return to port after they met the French passenger liner Flandre in the Azores. The Force de Raid escorted the liner back to port and arrived in Brest on 6 September.[15][16]

By this time, the German raiders had broken out into the Atlantic, so the British and French fleets formed hunter groups to track them down; the Force de Raid was split, with Dunkerque and Strasbourg operating individually as Force L and Force X, respectively. Dunkerque, the aircraft carrier Béarn, and three cruisers remained in Brest while Strasbourg and two French heavy cruisers joined the British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, based in Dakar, French West Africa. Strasbourg left Brest on 7 October in company with the destroyer Volta and a division of torpedo boats, meeting Hermes off Camaret-sur-Mer later that day. The ships then steamed south to meet the heavy cruisers off Casablanca, ultimately arriving in Dakar on 14 October. The ships went on a patrol in the central Atlantic from 23 to 29 October, during which they captured the German merchant ship Santa Fe on the 25th. Another sweep followed from 7 to 13 November to the west of Cape Verde; the ships found four Germans aboard a Belgian passenger liner and took them prisoner. Other warships arrived in Dakar on 21 November to relieve Strasbourg; she left that day along with the cruiser Algérie and an escort of torpedo boats. Ordered to return to Brest, it was feared that German aircraft had dropped naval mines in the harbor entrance, so the ships were temporarily diverted to Quiberon Bay until a search revealed no mines on 29 November.[17][18]

Faced with increasingly hostile posturing by Italy during the spring of 1940, the Force de Raid was dispatched to Mers-el-Kébir on 2 April. Strasbourg, Dunkerque, two cruisers, and five destroyers left that afternoon and arrived three days later. The squadron was quickly ordered to return to Brest just a few days later in response to the German landings in Norway on 9 April. The Force de Raid left Mers-el-Kébir that day and arrived in Brest on the 12th, with the intention that the ships would cover convoys to reinforce Allied forces fighting in Norway. But the threat of Italian intervention continued to weigh on the French command, which reversed the ships' orders and transferred them back to Mers-el-Kébir on 24 April; Strasbourg and the rest of the group left that day and arrived on 27 April. They conducted training exercises in the western Mediterranean from 9 to 10 May but saw little activity for the next month. On 10 June, Italy declared war on France and Britain.[19]

Two days later, Strasbourg and Dunkerque sortied to intercept reported German and Italian ships that were incorrectly reported to be in the area. The French had received faulty intelligence that had indicated that the Germans would attempt to force a group of battleships through the Strait of Gibraltar to strengthen the Italian fleet. After the French fleet got underway, reconnaissance aircraft reported spotting an enemy fleet steaming toward Gibraltar. Supposing the aircraft to have spotted the Italian battle fleet steaming to join the Germans, the French increased speed to intercept them, only to realize that the aircraft had in fact located the French fleet. The fleet then returned to port, marking the end of Strasbourg's last wartime operation.[20] On 22 June, France surrendered to Germany following the Battle of France.[13][21][22] Under the terms of the Armistice, Strasbourg and Dunkerque would remain at Mers-el-Kébir.[23]

Mers-el-Kébir

[edit]

The only test in battle for Strasbourg came in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July. The British, misinterpreting the terms of the armistice as providing the Germans with access to the French fleet, feared that the ships would be seized and pressed into service against them despite assurances from François Darlan, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, that if the Germans attempted to take the vessels, their crews would scuttle them. Prime Minister Winston Churchill then convinced the War Cabinet that the fleet must be neutralized or forced to re-join the war on the side of Britain.[24] The British Force H, commanded by Admiral James Somerville and centered on the battlecruiser HMS Hood and the battleships Resolution, and Valiant, arrived off Mers-el-Kébir to coerce the French battleship squadron to join the British cause or scuttle their ships. The French Navy refused, as complying with the demand would have violated the armistice signed with Germany. To ensure the ships would not fall into Axis hands, the British warships opened fire at 17:55. Strasbourg was tied alongside the mole with her stern facing the sea, so she could not return fire.[25][26]

Immediately after the British started shooting, Gensoul issued the order to get underway and return fire. Strasbourg, at that time commanded by Capitaine de vaisseau (Ship of the line captain) Collinet, was the first large warship to slip her mooring, following four destroyers on their way out of the harbor. Debris from near misses showered the ship as she made her way through the port; some of these fragments dented or punched holes in her hull, and burning debris scorched her deck. A salvo of 15-inch (380 mm) shells near-missed the ship at 18:00. As the vessels cleared the jetty, the destroyers steamed first ahead of Strasbourg to engage British destroyers off the harbor entrance and then arrayed themselves to her port side as the ships steamed east. Heavy smoke in the harbor from the destroyed battleship Bretagne, which had suffered a magazine explosion, masked the escape of Strasbourg and the destroyers, and Somerville was initially unaware that she had evaded his attack. Somerville had received a report from a patrolling Fairey Swordfish pilot that a Dunkerque-class battleship had left the harbor, but he refused to believe it, as he believed that a field of naval mines that had been laid earlier that morning would have prevented any escape.[27]

Upon clearing the harbor, the British destroyer HMS Wrestler, which had been tasked with watching the entrance, turned to lay a smoke screen to protect Force H from what appeared to be a destroyer attack. The effect was to help to obscure Strasbourg, which, as she increased speed from 15 to 28 knots (28 to 52 km/h; 17 to 32 mph), let out a large cloud of black smoke. The French ships steered for a gap in the defensive minefield to bring themselves under the protection of a battery of 240 mm (9.4 in) coastal guns on Cape Canastel. By this time, the destroyers Tigre and Lynx had arrayed themselves ahead of the ship while Le Terrible and Volta covered her to the rear. At 18:40, the two leading destroyers depth charged the British submarine Proteus, forcing her to take evasive action. At 19:00, the destroyers Bordelais and Trombe and the torpedo boat La Poursuivante arrived from Oran to help cover her withdrawal.[28]

By this time, Somerville had realized that Strasbourg had escaped and turned east in pursuit; he launched an air strike from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, hoping to slow Strasbourg, while he steamed ahead with Hood, two light cruisers, and several destroyers. The first wave of aircraft, six bombers carrying 250 lb (110 kg) bombs, attacked at 19:45; all of the aircraft missed and two were shot down by the heavy anti-aircraft fire from Strasbourg and the destroyers. Strasbourg was still belching thick, black smoke, the result of damage to one of her air intakes from fragments of the jetty; the problem could only be corrected by shutting down boiler room No. 2. This would have reduced her speed to 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), which was not an acceptable solution with Hood now in pursuit. By 20:25, Somerville broke off the chase, but a second flight from Ark Royal, armed with torpedoes, attacked at 20:45. As with the first strike, all of the aircraft missed. With night having fallen and Hood having disengaged, the boilers could be turned off. The thirty crewmen in the boiler room were found to have succumbed to the heat and fumes, five of whom died. Repairs to the intake were effected while still underway, and within an hour, the boilers could be used again.[29]

Collinet was still unsure whether Somerville was still pursuing him, so rather than head directly for Toulon, he steered for the south of Sardinia. Under strict radio silence to prevent Somerville from discovering his intentions, Collinet waited until Strasbourg was some 60 nmi (110 km; 69 mi) from San Pietro Island off the coast of Sardinia at 10:00 on 4 July before turning northwest to Toulon. The ship entered the harbor there at 21:10; her crew lined the deck and she was greeted with the crews from several heavy cruisers in the harbor who cheered and played "La Marseillaise", the French national anthem.[30]

Forces de haute mer

[edit]

On 6 July, the French naval command ordered Gensoul to return to Toulon; he arrived and raised his flag aboard Strasbourg later that day. Repairs to the damage incurred during the attack were completed quickly, and in August the command reorganized the fleet. The prewar units were dissolved between 8 and 12 August; during this period, Gensoul left the vessel on the 10th. Strasbourg was assigned to the 3rd Squadron and on 14 August she was taken into the shipyard in Toulon to have screens installed to protect the anti-aircraft gun crews. She emerged from the yard on 11 September and two weeks later, the naval command created the Forces de haute mer (High Seas Forces), with Strasbourg serving as its flagship under Amiral Jean de Laborde. At the time, the fleet also included the heavy cruisers Algérie, Foch, and Dupleix and the light cruisers Marseillaise and La Galissonnière.[31]

On 5 November, Strasbourg and all of the cruisers except Algérie sortied to receive the old battleship Provence, which had been damaged during the attack on Mers-el-Kébir and then repaired. Provence was escorted by a group of five destroyers, and the two units met off the Balearic Islands and arrived back in Toulon on 8 November. The next two years passed uneventfully, in large part due to the restrictions on French naval activities under the armistice with Germany. Training operations were limited to two per month, and the cruisers and destroyers had to alternate between periods of active service and reserve status with skeleton crews. Strasbourg went into drydock from 15 April to 3 May 1941 for periodic maintenance, and in December she steamed to visit Marseille for four days. The ship was drydocked again on 31 January 1942 for a major refit that included the installation of radar. Her anti-aircraft battery was also modified. The work was completed on 25 April and she returned to service on the 27th. She had to be drydocked for repairs that lasted for five days to her rudder motors in mid-July.[32]

Sinking at Toulon

[edit]

Following Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa on 8 November, Germany launched Case Anton in retaliation, moving to seize all of the so-called "Zone libre", the part of Vichy France that had up to that point remained unoccupied. Early on 27 November, elements of the German 7th Panzer Division approached the city with the intention of seizing the ships of the Forces de haute mer. At 05:30, de Laborde issued orders to his ships' crews to scuttle their vessels. Sabotage teams had already been preparing to destroy their ships, including stuffing the gun barrels with explosives, and once the order was given, teams passed through each ship with sledgehammers, smashing equipment that might be salvaged by the Germans and Italians including rangefinders, gyrocompasses, radios, and other valuable equipment. Boiler room personnel lit the boilers and shut off the water feeds to cause them to overheat and explode.[33]

The Germans reached the port at 05:50 and issued orders to de Laborde to hand over his ships; he informed them that they were already sunk. Strasbourg appeared to be undamaged, leading to confusion among the German officers, but the ship's seacocks had been opened and she was in the process of sinking to the harbor bottom. At 06:20, de Laborde ordered the sabotage team aboard Strasbourg to detonate the scuttling charges that would destroy the ship and prevent her from being simply sealed and re-floated. Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to scrap those that were too badly damaged to quickly return to service. The Italians deemed Strasbourg to be a total loss after she was re-floated on 17 July; they accordingly began to dismantle the vessel in port.[34]

The armistice between Italy and the Allies in September 1943 stopped these activities and the ship was then seized by the Germans. On 1 April 1944 they handed her back to the Vichy French authorities. Her wreck was then towed to the Bay of Lazaret, where she was placed in a "state of conservation". She was heavily bombed and sunk by US forces—including the battleship USS Nevada on 18 August, three days after Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France. She was raised for the second time on 1 October 1944 but found to be beyond repair, and used as a testbed for underwater explosions until condemned and renamed Q45 on 22 March 1955, to be sold for scrapping on 27 May that year.[35][34][36]

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Whitley's Battleships of World War II provides the 1,381 figure, while Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships states the crew numbered 1,431.[7][8] Garzke & Dulin confirm the 1,381 number, and further clarify that the crew was composed of 56 officers, 1,319 enlisted men, and six civilian crew members.[9]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Labayle-Couhat, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 19–22, 24–26.

- ^ Dumas, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c Dumas, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Breyer, p. 433.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, p. 259.

- ^ Whitley, p. 45.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 73.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Dumas, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Whitley, p. 50.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 66.

- ^ Rohwer, p. 2.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 66, 68.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Rohwer, pp. 6, 9.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 70.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Rohwer, pp. 21, 27, 29–30.

- ^ Dumas, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 72.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Rohwer, p. 31.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 75, 77.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 77, 79, 82.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 83.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, p. 84.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Jordan & Dumas, pp. 92–92.

- ^ a b Jordan & Dumas, p. 93.

- ^ Dumas, p. 75.

- ^ Havern.

References

[edit]- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and battle cruisers 1905–1970. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 978-0-356-04191-9.

- Dumas, Robert (2001). Les cuirassés Dunkerque et Strasbourg [The Battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg] (in French). Paris: Marine Éditions. ISBN 978-2-909675-75-6.

- Garzke, William H. Jr. & Dulin, Robert O. Jr. (1980). British, Soviet, French, and Dutch Battleships of World War II. London: Jane's. ISBN 978-0-7106-0078-3.

- Havern, Christopher B. (12 December 2016). "Nevada II (Battleship No. 36): 1916–1948". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Jordan, John & Dumas, Robert (2009). French Battleships 1922–1956. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-034-5.

- Labayle-Couhat, Jean (1974). French Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0445-0.

- Roberts, John (1980). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 255–279. ISBN 978-0-85177-146-5.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945 – The Naval History of World War Two. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Strasbourg (ship, 1936) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Strasbourg (ship, 1936) at Wikimedia Commons

- Dunkerque-class battleships

- World War II battleships of France

- Ships built in France

- Battleships sunk by aircraft

- Shipwrecks of France

- World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

- 1936 ships

- World War II warships scuttled at Toulon

- Ships sunk by US aircraft

- Maritime incidents in November 1942

- Maritime incidents in August 1944