Four Great Mountains (Taiwan)

The Four Great Mountains of Taiwan refers to a group of four prominent organizations in Taiwanese Buddhism.[1][2] The term draws its name from the Four Sacred Mountains of China, four mountains in mainland China that each hold sacred Chinese Buddhist sites. The founders of the institutions are collectively referred to as the Four Heavenly Kings of Taiwanese Buddhism.[3] Each of the "Four Heavenly Kings" corresponds to one cardinal direction, based on where their organization is located in Taiwan. The institutions that make up the "Four Great Mountains" of Taiwanese Buddhism are:

- North (Jinshan): Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山) founded by Master Sheng-yen (聖嚴, d. 2009)

- South (Dashu): Fo Guang Shan (佛光山) founded by Master Hsing Yun (星雲, d. 2023)

- East (Hualien): Tzu Chi Foundation (慈濟基金會) founded by Master Cheng Yen (證嚴)

- West (Nantou): Chung Tai Shan (中台山) founded by Master Wei Chueh (惟覺, d. 2016)

With exception of Tzu Chi, all of them belong to the Linji school of Chan Buddhism.

Traditional Four Holy Mountains

[edit]During the Japanese rule of Taiwan, most Taiwan Buddhist temples came to affiliate with one of four central temples, called "Four Holy Mountains" (台灣四大名山):

- North (Keelung): Yueh-mei Mountain (月眉山), founded by Master Shan-hui (善慧, d. 1945)

- North (New Taipei): Kuan-yin Mountain (觀音山), founded by Master Ben-yuan (本圓, d. 1947)

- Center (Miaoli): Fa-yun Temple (法雲寺), founded by Master Chueh-li (覺力, d. 1933)

- South (Kaohsiung): Chao-feng Temple (超峰寺), also founded by Yi-min (義敏, d. 1947)

Dharma Drum Mountain

[edit]

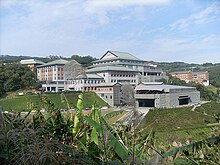

Dharma Drum Mountain is an international Buddhist spiritual, cultural, and educational foundation founded by Buddhist monk and scholar Master Sheng-yen (1930–2009).[4] The headquarters of the organization is located at Jinshan District, New Taipei City, Taiwan. Dharma Drum Mountain focuses on educating the public in Buddhism with the goal of improving the world and establishing a "Pure Land on Earth" through Buddhist education.[5]

The precursors to Dharma Drum Mountain were Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Culture (CHIBC) and Nung Chan Monastery founded by Dongchu, a prominent Chan monk and disciple of modernist monk, Grand Master Taixu.[6] CHIBC was founded in 1956 and was primarily active in promoting Buddhist culture through publishing journals. Nung Chan Monastery (literally: 'Farming Chan Monastery') was established in 1975. After Master Dongchu died in 1977, his Dharma heir, Sheng-yen became the new abbot of both Nung Chan and CHIBC. Both institutions grew rapidly, eventually overwhelming the building capacities.[7] In 1989, the institutions bought a plot of hilly land in Jinshan, New Taipei City, to build another monastery to expand to, which would become Dharma Drum Mountain.[8]

The architectural design of the monastery took seven years and followed and adjusted to the natural contour of the hills. Sheng-Yen personally oversaw the construction process.[9] The monastery broke ground in 1993 and was completed and inaugurated in 2001.[10] Dharma Drum Mountain at Jinshan is a complex of monasteries and education centers. Aside from being the international headquarters of Dharma Drum Mountain, it also serves as the campus of Dharma Drum Sangha University (DDSU),[11] Dharma Drum Buddhist College (DDBC)[12] and Dharma Drum University (DDU).[13]

The organization's main focus is on teaching Buddhism to the public with the goal of improving the world through Buddhist education and scholarship. The monastery describes its mission as including three types of education: education through academics, education through public outreach, and education through caring service. Dharma Drum Mountain also does charity work, but mostly does so indirectly through the funding of other charities.[8]

Dharma Drum Mountain has affiliated centers and temples in fourteen countries spread across North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania.[14]

Fo Guang Shan

[edit]

Fo Guang Shan monastery was founded in Dashu District, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, in 1967 by Buddhist monk Master Hsing Yun. The organization follows Humanistic Buddhism, which focuses on using Buddhism to improve the current world, as well as promotes Chinese culture, Buddhist education and charity.[5] The temple is known for its use of modern technology and teaching methods.[15][16] The organization's counterpart for laypeople is known as the Buddha's Light International Association.

In 1966, Hsing Yun purchased more than 30 hectares in Dashu Township, Kaohsiung County, as the site for the construction of a monastery. The groundbreaking ceremony was held on 16 May 1967.[17] In 2011, the monastery opened the Fo Guang Shan Buddha Museum (formerly called the Buddha Memorial Center), which was built with support from the Taiwanese government.[18][19]

The monastery is the largest Buddhist temple in Taiwan and is the most comprehensive of the "Four Great Mountains". The organization runs social and medical programs including a free medical clinic with mobile units that serve remote villages, local and international disaster and poverty relief, a children's and seniors' home, wildlife conservation areas, orphanages, and drug rehabilitation programs in prisons.[20] The monastery is best known for its education programs which include Buddhist colleges, full universities, various community colleges, and several primary schools. The monastery established several notable universities including Fo Guang University and Nanhua University in Taiwan and the University of the West in the United States.[21] Fo Guang Shan and Tzu Chi are the only "Four Great Mountains" that offer some form of strictly secular education, as opposed to purely religious.[20]

Fo Guang Shan's approach to Dharma propagation focuses on simplifying Buddhism in order to make it more appealing to the masses. The organization is known for utilizing modern marketing techniques and methods to preach such as the use of laser shows and multimedia displays.[16][20] Fo Guang Shan temples have no entrance fee, and do not allow many of the practices commonly found in other Chinese temples, such as fortune-telling or the presence of sales vendors.[16]

Fo Guang Shan entered mainland China in the early 21st century, focusing more on charity and Chinese cultural revival rather than Buddhist propagation in order to avoid conflict with the Chinese Communist Party, which opposes religion. In mainland China, Fo Guang Shan operates numerous cultural education programs and has built several libraries, publishing several books even through state controlled media.[16][22]

As of 2017, the order had over 1,000 monks and nuns, and over 1 million followers worldwide, with branches in fifty countries.[16]

Tzu Chi

[edit]

The Tzu Chi Foundation, known in full as the 'Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation', is a Taiwanese international humanitarian and non-governmental organization (NGO). The foundation was founded by Master Cheng Yen, a Taiwanese Buddhist nun, or bhikkhuni, in 1966 as a Buddhist humanitarian organization. The foundation has several sub-organizations such as the Tzu Chi International Medical Association (TIMA) and also the Tzu Chi Collegiate Youth Association (Tzu Ching). Although still Buddhist in nature, the organization focuses primarily on charity and humanitarian work rather than Buddhist propagation.[5] The foundation's work includes medical aid, disaster relief, and environmental work such as recycling. Tzu Chi is the largest Buddhist organization in Taiwan,[23] and also Taiwan's largest owner of private land.[24]

The Tzu Chi Foundation was founded as a charity organization with Buddhist origins by the Buddhist nun Master Cheng Yen on 14 May 1966 in Hualien, Taiwan, after Cheng Yen saw the humanitarian work of Christian missionaries in Taiwan in the post World War II period.[25] The organization began with a motto of "instructing the rich and saving the poor" as a group of thirty housewives who saved fifty cents (US$0.02) every day and stored them in bamboo savings banks to donate to needy families.[26][27]

The foundation expanded its work from helping needy families to medical aid in 1970, opening a medical clinic.[28][29] The foundation established its first hospital in Hualien in 1986 to serve the impoverished eastern coast of Taiwan.[28] The publicity from the extensive fundraising to build its first hospital is credited with helping Tzu Chi expand its membership rapidly during this period.[23][30] From 1987 to 1991, Tzu Chi membership doubled in size each year, by 1994, it boasted a membership of 4 million members.[23] Tzu Chi has since built hospitals in several more counties in Taiwan and built the Tzu Chi College of Nursing in 1989 which would become the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology and Tzu Chi College of Medicine in 1993 which would become Tzu Chi University.[31][32] In 1993, Tzu Chi began the first large scale bone marrow registry in the Taiwan.

Tzu Chi is most well known for its disaster relief programs. Although Buddhist in nature, Tzu Chi has a policy not preaching religion while giving aid.[30] One of the most iconic attributes of Tzu Chi disaster relief efforts is that volunteers not only provide short term aid but also partake in long term projects to rebuild the communities affected. Tzu Chi often builds new homes, schools, hospitals, and places of worship (including churches and mosques for non-Buddhists) for victims following a disaster.[33]

The foundation has policy of environmental protection and encourages the recycling of items such as water bottles as well as using reusable items or reusing items to reduce waste. As of 2014, the foundation operates over 5,600 recycling stations.[34] One of the foundation's projects is the recycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottles for the production of textiles.[35] Items made with the recycled resins include blankets, thermal underwear, T-shirts, hospital bed sheets, medical gowns, suitcases, stuffed animals and uniforms for Tzu Chi volunteers, these items are often used during its disaster relief programs.[36][37][34]

Tzu Chi is notably distinct from the other "Four Great Mountains" in respect to three main unique characteristics. First of all, the founder of the organization is a female. Secondly, the founder is not a Buddhist scholar who promotes a specific interpretation of Buddhism nor started any kind of religious movement. And finally, the organization is officially a charitable organization and Tzu Chi itself focuses primarily on humanitarianism and community service rather than Buddhist spiritual development.[38] Nuns at Tzu Chi practice spiritual contemplation only in the morning and evening, and spend the rest of the day doing charity or humanitarian work.[39]

Chung Tai Shan

[edit]

Chung Tai Shan is a Taiwan-based Buddhist monastic order founded in 1987 by the Chan meditation master and Buddhist monk Master Wei Chueh. Its headquarters is the Chung Tai Chan Monastery in Nantou, Taiwan, completed in 2001. Chung Tai Shan emphasizes meditation practice to purify the mind and encourages people to join the monastic life.[40]

Chung Tai Shan started in 1987, after Master Wei Chueh founded the Lin Quan Temple in Taipei County.[41] Due to the continuing growth of both lay disciples and monastic disciples, Master Wei Chueh founded Chung Tai Chan Monastery in Nantou, Taiwan, in 2001 and moved the order's headquarters to the new larger location.[41] Chung Tai Shan emphasizes meditation and strict adherence to the monastic lifestyle, the order follows a meditation technique developed by Master Wei Chueh known as "breath counting".[5]

Chung Tai Shan is the least socially engaged of the "Four Great Mountains", emphasizing purifying one's own mind and religious study over charity or disaster relief. It publishes a newspaper that is strictly religious in nature and its education programs are strictly Buddhist or highly laced by Buddhist content. The order also encourages lay members to adhere to the Eight Precepts on weekends.[5]

As of 2005, Chung Tai Shan's headquarters at Chung Tai Chan Monastery had about 1,600 monastics.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Ling, Haicheng (2005). Buddhism in China. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 9787508508405.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan S.; Tomatsu, Yoshiharu (2012-11-19). Buddhist Care for the Dying and Bereaved. Simon and Schuster. p. 111. ISBN 9781614290636.

- ^ Sakya, Madhusudan (2011). Current Perspectives in Buddhism: Buddhism today : issues & global dimensions. Cyber Tech Publications. pp. 64, 95, 98.

- ^ "The Founder of Dharma Drum Mountain". Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (2005-06-01). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives. 2005 (59). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. ISSN 2070-3449. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Dharma Drum Retreat Center: About Us: Meditation Classes, Meditation Retreat, Chan Meditation, Zen Retreat". Dharmadrumretreat.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ Sheng Yen, Footprints in the Snow: The Autobiography of a Chinese Buddhist Monk. Doubleday Religion, 2008. ISBN 978-0-385-51330-2

- ^ a b Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (2005-06-01). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives. 2005 (59). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. ISSN 1996-4617. Archived from the original on 2016-10-12. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ^ Drum of Life(documentary film). Dharma Drum Mountain Cultural Center

- ^ "Dharma Drum Mountain". www.dharmadrum.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ^ "瘜?曌?撅勗?找播憭批飛 | 擐???". Archived from the original on 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "www.ddbc.edu.tw | Home". Archived from the original on 2014-09-20. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "Dharma Drum University". Archived from the original on 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Dharma Drum Mountain: Global Affiliates Archived May 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harding, John S.; Hori, Victor Sōgen; Soucy, Alexander (2010-03-29). Wild Geese: Buddhism in Canada. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 283. ISBN 9780773591080. Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Ian (24 June 2017). "Is a Buddhist Group Changing China? Or Is China Changing It?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (1 June 2005). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives. 2005 (3). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. ISSN 2070-3449. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ "Regional Interfaith report". Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "佛光山佛陀紀念館". 佛光山佛陀紀念館. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (1 June 2005). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives. 2005 (59). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. ISSN 1996-4617. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE. p. 406. ISBN 9780761927297.

- ^ Johnson, Ian; Wu, Adam (24 June 2017). "A Buddhist Leader on China's Spiritual Needs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (2005). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives. 2005 (59). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "Why Tzu Chi is sparking resentment". Central News Agency. 6 March 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ O'Neill, Mark (2010-05-17). Tzu Chi: Serving with Compassion. John Wiley & Sons. p. 19. ISBN 9780470825679. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Wolkstein, Diane (2010). "THE DESIRE TO RELIEVE ALL SUFFERING". Parabola Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Biography of Dharma Master Cheng Yen". tw.tzuchi.org. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ a b Mark., O'Neill (2010-01-01). Tzu Chi: Serving with Compassion. John Wiley & Sons. p. 26. ISBN 9780470825679. OCLC 940634655. Archived from the original on 2017-03-19. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Jennings, Ralph (17 Nov 2014). "Taiwan Buddhists transform plastic waste". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ^ a b Mark., O'Neill (2010-01-01). Tzu Chi: Serving with Compassion. John Wiley & Sons. p. 28. ISBN 9780470825679. OCLC 940634655. Archived from the original on 2017-03-19. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Laliberté, André (2013-08-21). The Politics of Buddhist Organizations in Taiwan, 1989-2003: Safeguard the Faith, Build a Pure Land, Help the Poor. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 9781134353545.

- ^ "About Medicine Mission". Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Dharma Master Cheng Yen - Discovery Channel Documentary 證嚴法師 - Discovery 頻道 (中文字幕) 480p, 1 March 2014, archived from the original on 25 May 2017, retrieved 29 April 2017

- ^ a b Jennings, Ralph (17 November 2014). "Taiwan Buddhists transform plastic waste". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Tzu Chi Quarterly, Winter 2008

- ^ Foundation, Tzu Chi. "A Greener Blanket". Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Taiwan turns plastic junk into blankets, dolls". Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Hsin-Huang Michael, Hsiao; Schak, David (2005). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives (59). Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ MusicandCulture (2014-03-01), Dharma Master Cheng Yen - Discovery Channel Documentary 證嚴法師 - Discovery 頻道 (中文字幕) 480p, retrieved 2019-03-31

- ^ Schak, David; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (2005-06-01). "Taiwan's Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups". China Perspectives (in French). 2005 (59). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2803. ISSN 2070-3449. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ a b "Buddhist Grand Master Wei Chueh dies". Taipei Times. 10 April 2016. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.