Fortified wine

Fortified wine is a wine to which a distilled spirit, usually brandy, has been added.[1] In the course of some centuries,[2] winemakers have developed many different styles of fortified wine, including port, sherry, madeira, Marsala, Commandaria wine, and the aromatised wine vermouth.[3]

Production

[edit]

One reason for fortifying wine was to preserve it, since ethanol is also a natural antiseptic. Even though other preservation methods now exist, fortification continues to be used because the process can add distinct flavors to the finished product.[4][5]

Although grape brandy is most commonly added to produce fortified wines, the additional alcohol may also be neutral spirit that has been made from grapes, grain, sugar beets or sugarcane. Regional appellation laws may dictate the types of spirit that are permitted for fortification. For example, in the U.S. only spirits made from the same fruit as the wine may be added.[6]

The source of the additional alcohol and the method of its distillation can affect the flavour of the fortified wine. If neutral spirit is used, it is usually produced with a continuous still, rather than a pot still.[3]

When added to wine before the fermentation process is complete, the alcohol in the distilled beverage kills the yeast and leaves residual sugar behind. The result is a wine that is both sweeter and stronger, normally containing about 20% alcohol by volume (ABV).

During the fermentation process, yeast cells in the must continue to convert sugar into alcohol until the must reaches an alcohol level of 16–18%. At this level, the alcohol becomes toxic to the yeast and stalls its metabolism. If fermentation is allowed to run to completion, the resulting wine is (in most cases) low in sugar and is considered a dry wine. Adding alcohol earlier in the fermentation process results in a sweeter wine. For drier fortified wine styles, such as sherry, the alcohol is added shortly before or after the end of the fermentation.

In the case of some fortified wine styles (such as late harvest and botrytized wines), a naturally high level of sugar inhibits the yeast, or the rising alcohol content due to the high sugar kills the yeast. This causes fermentation to stop before the wine can become dry.[3]

Varieties

[edit]Commandaria wine

[edit]Commandaria is made in Cyprus' unique AOC region north of Limassol from high-altitude vines of Mavro and Xynisteri, sun-dried and aged in oak barrels. Recent developments have produced different styles of Commandaria, some of which are not fortified.

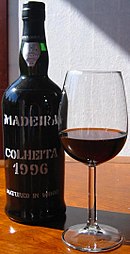

Madeira wine

[edit]

Madeira is a fortified wine made in the Madeira Islands. The wine is produced in a variety of styles ranging from dry wines which can be consumed on their own as an aperitif, to sweet wines more usually consumed with dessert. Madeira is deliberately heated and oxidised as part of its maturation process, resulting in distinctive flavours and an unusually long lifespan once a bottle is opened.

Marsala wine

[edit]Marsala wine is a wine from Sicily that is available in both fortified and unfortified versions.[7] It was first produced in 1772 by an English merchant, John Woodhouse, as an inexpensive substitute for sherry and port,[8] and gets its name from the island's port, Marsala.[7] The fortified version is blended with brandy to make two styles, the younger, slightly weaker Fine, which is at least 17% abv and aged at least four months; and the Superiore, which is at least 18%, and aged at least two years. The unfortified Marsala wine is aged in wooden casks for five years or more and reaches a strength of 18% by evaporation.[7]

Mistelle

[edit]Mistelle (Italian: mistella; French: mistelle; Spanish, Portuguese, Galician and Catalan: mistela, from Latin mixtella/mixtvm "mix") is sometimes used as an ingredient in fortified wines, particularly Vermouth, Marsala and Sherry, though it is used mainly as a base for apéritifs such as the French Pineau des Charentes.[9] It is produced by adding alcohol to non-fermented or partially fermented grape juice (or apple juice to make pommeau).[10] The addition of alcohol stops the fermentation and, as a consequence Mistelle is sweeter than fully fermented grape juice in which the sugars turn to alcohol.[11]

Moscatel de Setúbal

[edit]Moscatel de Setúbal is a Portuguese wine produced around the Setúbal Municipality on the Península de Setúbal. The wine is made primarily from the Muscat of Alexandria grape and is typically fortified with aguardente. The style was believed to have been invented by José Maria da Fonseca, the founder of the oldest table wine company in Portugal dating back to 1834.

Port wine

[edit]

Port wine (also known simply as port) is a fortified wine from the Douro Valley in the northern provinces of Portugal.[12] It is typically a sweet red wine, but also comes in dry, semi-dry and white or rosé styles.

Sherry

[edit]

Sherry is a fortified wine made from white grapes that are grown near the town of Jerez, Spain. The word "sherry" itself is an anglicisation of Jerez. In earlier times, sherry was known as sack (from the Spanish saca, meaning "a removal from the solera"). In the European Union "sherry" is a protected designation of origin; therefore, all wine labelled as "sherry" must legally come from the Sherry Triangle, which is an area in the province of Cádiz between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and El Puerto de Santa María.[13]

After fermentation is complete, sherry is fortified with brandy. Because the fortification takes place after fermentation, most sherries are initially dry, with any sweetness being added later. In contrast, port wine (for example) is fortified halfway through its fermentation, which stops the process so that not all of the sugar is turned into alcohol.

Sherry is produced in a variety of styles, ranging from dry, light versions such as finos to much darker and sometimes sweeter versions known as olorosos.[14] Cream sherry is always sweet.

Vermouth

[edit]

Vermouth is a fortified wine flavoured with aromatic herbs and spices ("aromatised" in the trade) using closely guarded recipes (trade secrets). Some of the herbs and spices used may include cardamom, cinnamon, marjoram, and chamomile.[15] Some vermouth is sweetened. Unsweetened or dry vermouth tends to be bitter. The person credited with the second vermouth recipe, Antonio Benedetto Carpano from Turin, Italy, chose to name his concoction "vermouth" in 1786 because he was inspired by a German wine flavoured with wormwood, an herb most famously used in distilling absinthe. Wine flavoured with wormwood goes back to ancient Rome. The modern German word Wermut (Wermuth in the spelling of Carpano's time) means both wormwood and vermouth. The herbs were originally used to mask raw flavours of cheaper wines,[16] imparting a slightly medicinal "tonic" flavor.

Vins doux naturels

[edit]

Vins doux naturels (VDN) are lightly fortified wines typically made from white Muscat grapes or red Grenache grapes in the south of France. As the name suggests, Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise, Muscat de Rivesaltes and Muscat de Frontignan are all made from the white Muscat grape, whilst Banyuls and Maury are made from red Grenache. Other wines, like those of Rivesaltes AOC, can be made from red or white grapes. Regardless of the grape, fermentation is stopped by the addition of up to 10% of a 190 proof (95% abv) grape spirit.[17] The Grenache vins doux naturels can be made in an oxidised or unoxidised style whereas the Muscat wines are protected from oxidation to retain their freshness.[18]

Vins de liqueur

[edit]A vin de liqueur is a sweet fortified style of French wine that is fortified by adding brandy to unfermented grape must. The term vin de liqueur is also used by the European Union to refer to all fortified wines. Vins de liqueur take greater flavour from the added brandy but are also sweeter than vin doux.

Examples include Floc de Gascogne which is made using 1/3 armagnac to 2/3 grape juice from the same vineyard, Pineau des Charentes in the Cognac zone, Macvin in Jura; there is also Pommeau similarly made by blending apple juice and apple brandy.

Low-end fortified wines

[edit]Inexpensive fortified wines, such as Thunderbird and Wild Irish Rose, became popular during the Great Depression for their relatively high alcohol content. The term wino was coined during this period to describe impoverished alcoholics of the time.[19]

These wines continue to be associated with the homeless, mainly because marketers have been aggressive in targeting low-income communities as ideal consumers of these beverages; organisations in cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland have urged makers of inexpensive fortified wine, including E & J Gallo Winery, to stop providing such products to liquor stores in impoverished areas.[20] In 2005, the Seattle City Council asked the Washington State Liquor Control Board to prohibit the sale of certain alcohol products in an impoverished "Alcohol Impact Area." Among the products sought to be banned were over two dozen beers, and six fortified wines: Cisco, Gino's Premium Blend, MD 20/20, Night Train, Thunderbird, and Wild Irish Rose.[21] The Liquor Control Board approved these restrictions on 30 August 2006.[22]

Gwaha-ju

[edit]Gwaha-ju is a fortified rice wine made in Korea.[23][24] Although rice wine is not made from grapes, it has a similar alcohol content to grape wine, and the addition of the distilled spirit, soju, and other ingredients like ginseng, jujubes, ginger, etc., to the rice wine, bears similarity to the above-mentioned fortified wines.

Terminology

[edit]Fortified wines are often termed dessert wines in the United States to avoid association with hard drinking.[25] The term "vins de liqueur" is used by the French.[26]

Under European Union legislation, a liqueur wine is a fortified wine that contains 15–22% abv, with Total Alcoholic Strength of no less than 17.5%, and that meets many additional criteria. Exemptions are allowed for certain quality liqueur wines.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lichine, Alexis (1987). Alexis Lichine's New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 236. ISBN 0-394-56262-3.

- ^ DuBose, Fred; Spingarn, Evan (2004). The Ultimate Wine Lover's Guide 2005. Barnes & Noble. p. 202. ISBN 9780760758328. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

Exactly when stronger wines or spirits began to be added to wine to preserve it is lost to history, but it worked — and fortified wine was born. History does record how the fortified wines Port and Madeira came to be.

- ^ a b c Robinson, Jancis, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ "Types of Fortified Wines You Might Enjoy Before or After Dinner". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Antonello, Biancalana. "DiWineTaste Report: Tasting Fortified Wines". DiWineTaste. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ "26 U.S. Code §5382 b(2)". Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Halley, Ned (2005). The Wordsworth Dictionary of Drink: An A–Z of Alcoholic Beverages. Wordsworth Editions. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-84022-302-6. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Hailman, John R. (2006). Thomas Jefferson on Wine. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 306. ISBN 978-1-57806-841-8. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

Marsala wine.

- ^ Robinson, Jancis, ed. (1999). "Mistela". The Oxford companion to wine (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866236-X. OCLC 41660699.

- ^ "mistelle Definition in the Wine Dictionary at Epicurious.com". epicurious.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Biancalana, Antonello. "Production of Fortified Wines". DiWineTaste. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Porter, Darwin; Price, Danforth (2000). Frommer's Portugal (16th ed.). IDG Books Worldwide. ISBN 0-02-863601-5.

- ^ "Spanish law". Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Sherry types". SherryNotes. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Paul (15 August 2008). "The Truth About Vermouth: The secret ingredient in today's top cocktails remains misunderstood". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Foley, Ray (2006). Bartending For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-470-10752-2. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Baxevanis, John J. (1987). The Wines of Champagne, Burgundy, Eastern and Southern France. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8476-7534-0. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "thewinedoctor.com". Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Zraly, Kevin (2006). Kevin Zraly's American Wine Guide. New York: Sterling. p. 238. ISBN 1-4027-2585-X.

- ^ Jorgensen, Janice (1993). Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands: Consumable Products. Detroit: St. James Press. p. 492. ISBN 1-55862-336-1.

- ^ Castro, Hector (7 December 2005). "City could soon widen alcohol impact areas". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. [dead link]

- ^ "Public Safety - Alcohol Impact Areas". Beacon Alliance of Neighbors. City of Seattle. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Yu, Tae-jong. "Gwaha-ju". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Park, Rock Darm (12 April 2012). "Gwaha-ju". Naver (in Korean). Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Charles L. (1998). A Companion to California Wine: An Encyclopedia of Wine and Winemaking from the Mission Period to the Present. University of California Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-520-92087-3. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Joseph, Robert (2006). Wine Travel Guide to the World. Footprint Handbooks. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-904777-85-4. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 479/2008; Annex IV, §3 (European Union document". p. 46.

External links

[edit]- Commandaria wine and its evolution.

- Dessert Wines (fortified wine production).

- Fortification calculator

- Fortified Wines