Fort Saint-Privat

| Fort Saint-Privat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 49°27′14″N 6°49′59″E / 49.454°N 6.833°E |

| Type | Von Biehler fort |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1872–1875 |

| Fate | Unused |

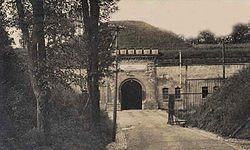

Fort Saint-Privat (Feste Prinz August von Württemberg before 1919) is a fortification near Metz. Part of the forts of Metz, it had its baptism of fire in late 1944 during the Battle of Metz.

History

[edit]Fort Saint-Privat is part of Metz' first fortified belt, designed during the Second French Empire by Napoléon III. The belt consists of Fort Saint-Privat (1870), Fort de Queuleu (1867), Fort des Bordes (1870), Fort de Saint-Julien (1867), Fort Gambetta, Fort Déroulède, Fort Decaen, Fort de Plappeville (1867) and the St. Quentin fortifications (1867). Most of the forts were unfinished in 1870, when the Franco-Prussian War began. Under German control, Metz initially had a German garrison of 15,000 to 20,000 men,[1] exceeded 25,000 before World War I[2] and gradually became the premier stronghold of the German Reich.[3]

Construction and facilities

[edit]The fort, built by German engineers from 1872 to 1875, was designed in a style similar to the "detached fort" concept developed by Hans Alexis von Biehler in Germany. The goal was to form an enclosure around Metz of forts and artillery, with a variety of guns and spaces between them.

Assignments

[edit]In 1890, the forts were staffed by German Corps XVI troops from Metz and Thionville. The 145th King's Infantry Regiment (6th Lorrain) garrisoned the fort before 1914. Invested by the French army in 1919, the Prinz August von Württemberg Fort was renamed Fort Saint-Privat. It was soon encompassed by the perimeter of the Metz-Frescaty Air Base, which was developed after World War I. The fort was captured in 1940 by the Wehrmacht, which held it until 1944. It is no longer in use.

Second World War

[edit]On September 2, 1944, Metz was declared a Reich fortress by Adolf Hitler. The fortress was to be defended to the last by German troops, whose leaders had sworn allegiance to Hitler.[4] Faced with the 5th American Division, the German 462nd Infantry Division defended the Reich. When fighting began in September, its defense was commanded by Waffen-SS Colonel Ernst Kemper. During the Battle of Metz, several units succeeded each other in the fort.

On November 9, 1944 (before to the attack on Metz) the United States Air Force sent 1,299 heavy bombers, B-17s and B-24s, dumping 3,753 tons of bombs and 1,000 to 2,000 pounds of ammunition on fortifications and strategic points in the combat zone of the US Third Army.[5] Most of the bombers dropped their payloads blind from over 20,000 feet, and military targets were often missed. In Metz 689 loads of bombs hit the seven forts identified as priority targets, causing collateral damage and demonstrating the practical inadequacy of massively bombing military targets.[6]

The final attack arrived from the south and west on November 16, 1944. Facing the 11th Infantry Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division, the 462nd Infantry Division resisted with German MG 34 and MG 42 machine guns. Troops commanded by Lieutenant General Heinrich Kittel defended the airfield's hangars and air raid shelters before falling back towards Fort Saint-Privat and the last hangars. During the cold, wet night of November 16, 1944, the 11th Infantry regiment lost four officers and 118 men on the ground;[7] German losses were also heavy. Fighting resumed northeast of the base (where a German section clung to the last buildings) the following day, with shots fired primarily from Fort Saint-Privat.

The fort was commanded by Werner Matzdorff (1912–2010), a Waffen-SS Sturmbannführer and a Schutzpolizei major.[8] Matzdorff commanded his troops with an iron fist, knowing that he could not hold out for long. Entrenched in the fort, he refused to surrender. On November 20, Matzdorff emerged from the fort with a white flag. The 11th Infantry commander thought that he was surrendering, but Matzdorff said that he and his men were ready to fight to the death "if necessary" and only wanted to evacuate twenty of his most severely-wounded men.[9] On November 21, General Kittel (who was wounded in the Riberpray barrack) was captured, and Metz was liberated at 14:35 the following day. That evening, the troops at Fort Saint-Privat began surrendering to the Americans. Although morale in the fort was low, resistance was fierce.[9]

After a week the situation became critical, with shortages of food and ammunition. On November 29, Matzdorff agreed to surrender unconditionally with 22 officers and 488 men (80 of whom were wounded and without care for over a week).[10] The swastika no longer flew over the air base.[note 1] The German General Staff objective, to play for time by stalling US troops as long as possible ahead of the Siegfried Line, was largely achieved.[citation needed]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ René Bour (1950), Histoire de Metz, p. 227.

- ^ Philippe Martin (October 18, 2007), "Metz en 1900", L'Express, no. 2937.

- ^ François Roth, "Metz annexée à l’Empire allemand", in François-Yves Le Moigne, Histoire de Metz, Toulouse, Privat, 1986, p.350.

- ^ René Caboz [in French] (1984), Éditions Pierron (ed.), La bataille de Metz, Sarreguemines, p. 132

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ Général Jean Colin (1963), Académie nationale de Metz (ed.), Contribution à l'histoire de la libération de la ville de Metz ; Les combats du fort Driant (septembre-décembre 1944), p. 13.

- ^ (Cole 1950, p. 424).

- ^ (Cole 1950, p. 442).

- ^ Hans Stöber; Helmut Günther (1976), Osnabrück, Munin (ed.), Die Sturmflut und das Ende. Die Geschichte der 17. SS-Panzerdivision "Götz von Berlichingen" (in German), vol. 2, pp. 141–156

- ^ a b (Kemp 1994, pp. 340–341).

- ^ (Kemp 1994, p. 400).

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Cole, Hugh M. (1950), The Lorraine Campaign, Washington, Center of Military History

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kemp, Anthony (1994), Heimdal (ed.), Lorraine – Album mémorial – Journal pictorial : 31 août 1944 – 15 mars 1945.