Fort Madison (Alabama)

| Fort Madison | |

|---|---|

| Suggsville, Alabama in United States | |

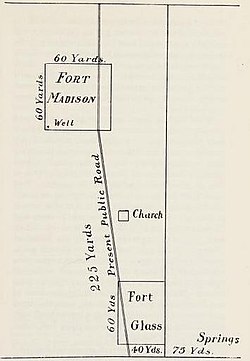

Sketch of Fort Madison and Fort Glass | |

| Coordinates | 31°31′27″N 87°43′14″W / 31.52417°N 87.72056°W[1] |

| Type | Stockade fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Controlled by | Private |

| Open to the public | No |

| Site history | |

| Built | July 1813 |

| Built by | Mississippi Territory settlers |

| In use | 1813 |

| Battles/wars | Creek War |

Fort Madison was a stockade fort built in August 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama (then Mississippi Territory), during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was built by the United States military in response to attacks by Creek warriors on encroaching American settlers. The fort shared many similarities to surrounding stockade forts in its construction but possessed a number of differences in its defenses. The fort housed members of the United States Army and settlers from the surrounding area, and it was used as a staging area for raids on Creek forces and supply point on further military expeditions. Fort Madison was subsequently abandoned at the conclusion of the Creek War and only a historical marker exists at the site today.[2]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The Creek War of 1813 was initially a civil war between two factions of the Creek nation, the Creek national government and the rebellious Red Sticks. The United States government was involved in the War of 1812 against Britain, but joined the Creek War in support of the government faction. The United States hoped to prevent the Red Sticks from becoming a British ally, to break the remaining Creek power in the southern United States, and to annex Creek territory.[3]

In retaliation, the Red Sticks began attacking American settlers and their homesteads. The settlers built protective stockades due to these attacks, since they were unsure if the United States military would offer them any assistance due to fact they were squatters on public lands. Many of these forts were named for the settlers who owned the land the stockade was built on. In addition to these protective stockades, the United States military constructed forts as staging areas for planned military action against the Creeks.[2]

Construction

[edit]In July 1813 Fort Glass was built as a protective stockade around the home of Zachariah Glass by local settlers in present-day Clarke County, Alabama.[4] After the Battle of Burnt Corn, General Ferdinand Claiborne feared retaliatory attacks by the Red Sticks against local settlers. Claiborne sent Colonel Joseph Carson with between 150-200 mounted soldiers from the Mount Vernon Cantonment to Fort Glass as reinforcements to protect the local settlers.[5][6][7] These soldiers arrived on August 10, 1813 and soon began constructing a new fort 225 yards northwest of Fort Glass to house themselves.[6][8][9] Some of these soldiers had joined soldiers from Fort Mims and participated in the Battle of Burnt Corn.[10] The fort differed from surrounding forts in that it was not named for a local landowner but was named after then-President James Madison.[11] Fort Madison was constructed on a dividing ridge between Alabama River and Tombigbee River.[12] The fort was located on a strategically important site as the first store in the area was located six miles due east, one of the first grist mills four miles north, and the first cotton gin was located two miles north.[13]

Fort Madison was made of 15-foot hewn pine logs that were sharpened at the top and buried three feet deep. The fort was square with each side being 60 yards in length.[2] Fort Madison additionally differed from surrounding forts in that it had blockhouses at each corner, providing additional protection from attackers.[14] Scattered throughout the walls were strategically placed gunholes to offer additional protection.[11] In addition, the blockhouses and roofs were covered with clay to hamper the wood from being caught on fire by attackers.[15]

Most forts and protective stockades at this time used fatwood placed on the top of the stockades to light the area surrounding the fort at night.[11] In addition to the traditional lighting method, Fort Madison employed a more-sophisticated lighting mechanism. Two differing descriptions exist of Fort Madison's lighting mechanism: Evan Austill's grandson (Austill reportedly helped design the lighting structure[16]), described the mechanism as "...a tall pine pole erected in the middle of the fort, and built around it a scaffolding with a hole in the center so that it could be raised by pushing it up the pole. On this, earth was placed so that the burning pine would not ignite the boards. On this a light was kept burning at night...."[17] Samuel Dale, who himself was an occupant of Fort Madison, described it as "two poles, fifty feet long, were firmly planted on each side of the fort; a long lever, upon the plan of a well-sweep, worked upon each of these poles; to each lever was attached a bar of iron about ten feet long, and to these bars we fastened, with trace-chains, huge fagots of light-wood".[15]

After construction, the fort held somewhere between 30-40 families to 700 overall inhabitants.[18][19]

Military use

[edit]

After completion of Fort Madison, Colonel Carson moved the headquarters of his military district (which included the area between the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers), from Fort Stoddert to Fort Madison.[21] Soldiers were moved between different forts in the area during this time—after the construction of Fort Mims, 40 soldiers under the command of a Lieutenant Bowen were sent by General Claiborne to garrison Fort Madison while 16 troops under the command of Lt. S. M. Osborne were transferred from Fort Madison to Fort Mims.[21][22]

On August 21, a Choctaw warrior brought news to Fort Easley that warned of 400 Red Stick warriors and a number of Choctaw warriors from the village of Turkey Town were planning to attack Fort Easley and Fort Madison in the coming days. This news proved to be false, as the actual attack occurred at Fort Mims on August 30 in what became known as the Fort Mims massacre.[23] Two days later, Red Stick warriors under the command of Josiah Francis (Hillis Hadjo) attacked settlers who had left the protection of Fort Sinquefield. The warriors killed 11-12 women and children in what became known as the Kimbell-James massacre.[24] When news of this second massacre reached Fort Madison, Colonel Carson sent a detachment of 11 troops to assist in the burial of the victims.[25] That night Jeremiah Austill (son of Evan Austill), left Fort Madison on horseback to deliver news of the massacre to General Claiborne at Mount Vernon—only stopping for rest at Fort Carney.[26] The next day, Red Stick warriors attacked Fort Sinquefield itself but after killing two of the occupants were driven off by some of the soldiers from Fort Madison.[24] After this second attack all the remaining occupants of Fort Sinquefield fled to Fort Madison, along with many of the occupants of Fort Glass and nearby Fort Lavier.[27]

Following the Fort Mims and Kimbell-James massacres, General Thomas Flournoy and General Claiborne decided to abandon the settler stockades and concentrate their forces in more defensible areas.[12][19] On September 8, General Claiborne sent Colonel Carson discretionary orders to abandon Fort Madison if he felt he could not properly protect it and fall back to Fort St. Stephens.[28] Carson debated abandoning the fort and reluctantly ordered his troops to leave Fort Madison on September 10.[8] The settlers were also given the recommendation to leave, but Evan Austill stated that if 50 people would remain at the fort he would command them in its defense.[19] Contrasting this, Dale later reported in interviews that he himself actually was in command of the only 80 persons who remained behind at Fort Madison.[12][17][28] Austill and Dale were each made captains of separate militia companies made up of men who remained behind at Fort Madison. Both captains had previous experience with American-Native American relations: Austill had served as an Indian agent with the Cherokee in Georgia prior to moving to the Mississippi Territory and Dale had recently been wounded at the Battle of Burnt Corn.[29][30] After Carson departed, Colonel John Haynes was left in overall command of the fort.[8]

While the small number of settlers remained in the fort, Red Stick warriors continually reconnoitered the fort's strength. William Weatherford even disguised himself as a local settler and gained access to Fort Madison, concluding it was too strong to attack.[31] Austill and Dale had women wear hats and uniforms to appear as if there were a larger number of soldiers in the fort along with using the lighting mechanism to provide constant aid in surveillance.[15] The settlers did not leave the fort for two weeks and shot any hogs or cattle that came within musket range for food.[15] Realizing the settlers were not abandoning the fort, Claiborne allowed Carson and 250 soldiers to return to Fort Madison.[19] After the soldiers' arrival, parties were sent out searching for Red Stick warriors who had destroyed surrounding farmsteads.[19][32] Other parties were sent to obtain food from their own farms, with some facing death at the hands of waiting Red Sticks.[33] One of these scouting expeditions led to the subsequently notable Canoe Fight, in which Dale, Jeremiah Austill, James Smith, and a free Black named Caesar killed ten Red Stick warriors.[19][34] In addition to military and militia members, friendly Choctaws also participated in scouting the Alabama River Valley.[35]

In November 1813, General Claiborne advanced his command from St. Stephens to Fort Madison. Soon after, he crossed to the east side of the Alabama River and began construction on Fort Claiborne.[36] Fort Madison was used as a stopover on journeys between Fort Claiborne and St. Stephens.[35] Pushmataha and his Choctaw warriors stopped at Fort Madison on their way to the Battle of Holy Ground and were given 20 new rifles in preparation for the battle.[37]

After the Battle of Holy Ground, militia from Fort Madison under the command of Austill joined with a cavalry company and formed a battalion under the command of Dale. This battalion marched under Colonel Gilbert C. Russell in his failed attempt to attack Creek towns along the Cahaba River.[38]

Postwar

[edit]Fort Madison lent its name to one of the early major neighborhoods of Clarke County. The community also had a local cemetery.[2] A subsequent community grew around the site of Fort Madison and was known as "Allen".[39]

The approximate site of Fort Madison has been identified and archaeological surveys have been made of the area, but no defining features or artifacts have been found.[40] A historical marker was placed by a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in the early 1900s and is located near the site of Fort Madison.[41][42] The burial site of Evan Austill is located a short distance away from the Fort Madison historical marker.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ "GNIS Detail - Fort Madison". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form". Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Braund, Kathryn. "Creek War of 1813-1814". Alabama Humanities Alliance. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Harris 1977, pp. 109.

- ^ Claiborne 1860, pp. 94.

- ^ a b Pickett 1878, pp. 526.

- ^ Waselkov 2006, pp. 104.

- ^ a b c Creagh 1847, pp. 4.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Claiborne 1860, pp. 72.

- ^ a b c Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 110.

- ^ a b c Claiborne 1860, pp. 116.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 109.

- ^ Stowe, Noel R.; Hoyt, Marvin (1975). Olsen, Susan C. (ed.). Archeological Investigations at Fort Mims (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

Archeological Completion Report Series, Number 4.

- ^ a b c d Claiborne 1860, pp. 117.

- ^ Bunn, Mike; Williams, Clay. "Evans Austill Gravesite". The Creek War and the War of 1812. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 203.

- ^ Ball 1994, pp. 318.

- ^ a b c d e f Austill 1847, pp. 2.

- ^ Lossing 1868, pp. 751.

- ^ a b Thrapp 1991, pp. 234.

- ^ Holmes 1847, pp. 5.

- ^ Claiborne 1860, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Bunn, Mike. "Fort Sinquefield". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 185.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 202.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 197.

- ^ a b Pickett 1878, pp. 547.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 131.

- ^ Ball 1994, pp. 459.

- ^ Weir 2016, pp. 262.

- ^ Pickett 1878, pp. 561.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 223.

- ^ Creagh 1847, pp. 5.

- ^ a b Gaines 2014, pp. 64.

- ^ Creagh 1847, pp. 6.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 241.

- ^ Eggleston 1878, pp. 227.

- ^ Foscue 1989, pp. 7.

- ^ Braund 2012, pp. 250.

- ^ Bunn, Mike; Williams, Clay. "Fort Madison". The Creek War and the War of 1812. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ "Fort Madison-Creek War 1812-13". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 205.

Sources

[edit]- Austill, Jeremiah (1847). Pickett, Albert James (ed.). Interesting Notes upon the History of Alabama. Vol. 1. Montgomery, Alabama: Alabama Department of Archives and History.

- Ball, Timothy Horton (1994) [1882]. A Glance into the Great South-East, or Clarke County, Alabama, and its surroundings, from 1540 to 1877. Grove Hill, Alabama: Clarke County Historical Society. OCLC 1009338180.

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (2012). Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War & the War of 1812. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5711-5.

- Claiborne, J. F. H. (1860). Life and Times of Gen. Sam Dale, the Mississippi Partisan. New York, New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 9781015473249.

- Creagh, G. W., Colonel (1847). Pickett, Albert James (ed.). Interesting Notes upon the History of Alabama. Vol. 2. Montgomery, Alabama: Alabama Department of Archives and History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eggleston, George Cary (1878). Red Eagle and the Wars with the Creek Indians of Alabama. New York, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 9780548127322.

- Foscue, Virginia (1989). Place Names in Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0410-X.

- Gaines, George Strother (2014). Pate, James P. (ed.). The Reminiscences of George Strother Gaines. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817388812.

- Halbert, Henry; Ball, Timothy (1895). The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Chicago, Illinois: Donohue & Henneberry. ISBN 9781375702775.

- Harris, W. Stuart (1977). Dead Towns of Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1125-4.

- Holmes, Thomas G., Dr. (1847). Pickett, Albert James (ed.). Interesting Notes upon the History of Alabama. Vol. 4. Montgomery, Alabama: Alabama Department of Archives and History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. New York, New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 9780781251136.

- Pickett, Albert James (1878). History of Alabama, and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Willo Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1363310845.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography. Vol. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9418-2.

- Waselkov, Gregory A. (2006). A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-1814. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama. ISBN 0-8173-1491-1.

- Weir, Howard (2016). A Paradise of Blood: The Creek War of 1813–14. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme. ISBN 1-59416-270-0.