Fort DuPont

39°34′17″N 75°35′01″W / 39.57139°N 75.58361°W

| Fort DuPont | |

|---|---|

| Part of Harbor Defenses of the Delaware | |

Parade grounds at Fort DuPont | |

| Type | Fortification |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Public - State of Delaware |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Fort DuPont Historic District | |

Fort DuPont aerial view 1927, Abbot Quad mortar battery in center | |

| Location | Delaware City, Delaware |

| Area | 350 acres (140 ha) |

| Built | 1863–1945 |

| Architect | Army Corps of Engineers Army Quartermaster Department |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 99001275[1] |

| Added to NRHP | 1999 |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1863–1864, 1870–1875, 1897–1904, 1941–1942 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1863–1875, 1899–1924, 1941–1945 |

| Materials | Reinforced concrete, earth |

Fort DuPont, named in honor of Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont, is located between the original Delaware City and the modern Chesapeake and Delaware Canal on the original Reeden Point tract, which was granted to Henry Ward in 1675. Along with two other forts of the Harbor Defenses of the Delaware, it defended the Delaware River and the water approach to Philadelphia from 1900 through 1942. In 1992 a portion was redesignated as Fort DuPont State Park, which became Delaware's 13th state park. In 2016, the acreage which is not in the state park system was annexed into Delaware City.

The first fortification built was the Ten Gun Battery, an auxiliary to nearby Fort Delaware during the American Civil War.[2] The Twenty Gun Battery was constructed on the reservation during the 1870s, later followed by a mine control casemate for an underwater minefield in 1876.[3] In 1897-1904, Endicott-era emplacements were constructed for long-range rifles, mortars, and rapid-fire guns.[4] In 1922 the post became headquarters for the 1st Engineer Regiment, which remained at the post until 1941. During World War II, Fort DuPont served as a mobilization station for deploying units, and contained a prisoner-of-war camp for captured German soldiers and sailors. After the war, Fort DuPont was declared surplus and offered to the Veterans Administration for use as a veterans hospital. After they declined, the state bought the site at a 100 percent discount and adapted existing structures for reuse. In 1948, it officially opened as the Governor Walter W. Bacon Health Center.

In 1999 the site was officially designated the Fort DuPont Historic District after it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[5] The historic district comprises Fort DuPont State Park and the Governor Bacon Health Center.[6][7] The site is currently being redeveloped by the Fort DuPont Redevelopment and Preservation Corporation.

Civil War through 1885

[edit]Ten Gun Battery, briefly called Fort Reynolds,[8] was built from 1863 to 1864 on the property of 1st Lt. Clement Reeves of the 5th Delaware Volunteer Infantry. The first soldiers to garrison the post were from Capt. John Jay Young's Independent Battery G, also called the Pittsburgh Heavy Artillery.[8] Sgt. Bishop Crumrine of Young's Battery wrote, "This fortification is not properly a Fort but rather a water battery. Situated just across the river from Fort Delaware on the Delaware City side, it has five sides. The two longest sides being next to the river is a heavy breast work on which six 10-inch and four 15-inch Rodman guns are mounted."[8] The battery was rebuilt as the Twenty Gun Battery in the 1870s. It was to house both heavy guns and coast defense mortars, but was not fully armed.[9] In 1876 a mine casemate was built for an underwater minefield.[3]

Plan by Lt. Col. Henry Brewerton

1885 through Spanish–American War

[edit]In 1885 the Board of Fortifications chaired by Secretary of War William C. Endicott made sweeping recommendations for new coast defenses. Most of these recommendations were adopted in what became known as the Endicott program. Before the Spanish–American War and continuing in the following few years, major construction took place to upgrade the defense capabilities of the three forts defending the major ports along the Delaware River. Fort Mott and Fort DuPont were built essentially from scratch, and a new heavy gun battery was constructed inside Fort Delaware. At all three forts, Endicott-era batteries were built that mounted long-range rifles, mortars, and rapid-fire guns. Construction at Fort DuPont began in 1897, with all but one battery completed by the end of 1900.[9]

Batteries Rodney and Best, with eight 12-inch (305 mm) mortars each, were the largest batteries at the fort. All sixteen mortars were named Battery Rodney in 1902, then split in 1906. These were in an "Abbot Quad" battery of four pits with four mortars each, arranged in a square and enclosed and separated by high walls of earth and concrete for maximum protection against enemy fire. This was typical of early Endicott mortar installations and was also intended to concentrate the mortars' fire. However, it was soon found to be too cramped for efficient reloading and later batteries had a linear, open-back arrangement. Batteries Read and Gibson mounted two 12-inch (305 mm) guns and two 8-inch (203 mm) guns, the former on barbette carriages and the latter on disappearing carriages. These were in an unusual combined battery, with the 12-inch guns of Battery Read on either side of the pair of 8-inch guns of Battery Gibson. Battery Ritchie had two 5-inch (127 mm) guns on pedestal mounts. Battery Elder, completed in 1910, had two 3-inch (76 mm) guns on pedestal mounts. These small-caliber guns were intended to protect the minefield from minesweepers, and were called "mine defense guns".[9][10][11]

Battery Rodney was named for Caesar Rodney, signer of the Declaration of Independence and a major general in the Delaware militia. Battery Best was named for Major Clermont L. Best, an artillery officer in the Spanish–American War who died in 1903. Battery Read was named for George Read, signer of the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution, and U.S. senator. Battery Gibson was named for Colonel James Gibson, killed in the War of 1812 at Fort Erie, Canada. Battery Ritchie was named for Captain John Ritchie, an artillery officer killed in the War of 1812 at Lundy's Lane, Canada. Battery Elder was named for Samuel S. Elder, an artillery officer in the Civil War who died in 1885.[9]

On July 22, 1899, Army General Orders, No. 134, officially designated the "battery at Delaware City" as Fort DuPont, named in honor of Rear Adm. Samuel Francis Du Pont.[12] During this time, according to the Fort DuPont Flashes, the post was garrisoned by soldiers of the 4th U.S. Artillery under the command of Maj. Van Arsdale Andruss. Fort DuPont included the headquarters for the three-fort complex, and had more barracks and administrative buildings than the other two forts. In 1901 the heavy artillery companies garrisoning forts were redesignated as coast artillery companies under the Artillery Corps, and in 1907 they became part of the new U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps. On completion Forts DuPont, Delaware, and Mott were an artillery district, redesignated in 1913 as the "Coast Defenses of the Delaware".[13]

World War I

[edit]The overcrowding situation in the mortar battery was relieved by transferring half the mortars (two mortars per pit) to batteries under construction elsewhere. Four of Battery Best's mortars were transferred to Fort Ruger, Hawaii in 1913, and four of Battery Rodney's mortars were transferred to Fort Rosecrans, San Diego, California in 1918. During World War I, Fort DuPont continued serving the role of coastal defense as well as training post for local draftees and deploying artillery units. In 1915, Batteries Read and Gibson were declared obsolete.[14] Following the American entry into World War I, in 1917 Battery Gibson's 8-inch (203 mm) guns were dismounted for potential use as railway artillery on the Western Front. The carriages were dismounted in 1918 and scrapped in 1922. In 1918 Battery Read's 12-inch (305 mm) guns were transferred to Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn, New York. One carriage was scrapped in 1918, one was sent to Fort Hancock, New Jersey. Battery Ritchie's pair of 5-inch (127 mm) guns were transferred to an "emergency battery" at Fisherman's Island, Virginia in 1917–1918. None of the removed guns were ever returned to the fort.[9] Units such as the 7th Trench Mortar Battalion used Fort DuPont for basic and advanced training before heading to France in October 1918.[15] A two-gun antiaircraft battery with M1917 3-inch (76 mm) AA guns was built at the fort in 1918.[3]

Between the wars

[edit]Fort Saulsbury near Slaughter Beach, Delaware, built 1917–1920 and accepted for service in 1924, effectively replaced the three forts near Delaware City, though these retained mortars, mines, and some guns through early World War II. Fort Saulsbury had four 12-inch (305 mm) guns on long-range barbette carriages and was sited to engage the enemy much further down the estuary than the earlier forts. The Harbor Defenses of the Delaware was one of the most extreme examples of coast defense forts being built further seaward as gun ranges increased.[16] Following World War I, Fort DuPont transitioned to a quartermaster depot and also became an engineer post with the arrival of the First Engineers in May 1922. During this time, Battery E, 7th Coast Artillery was the caretaker detachment for the Coast Artillery Corps facilities at Fort DuPont and the other Delaware River forts. On December 12, 1932, six sets of officers' quarters were floated to Fort DuPont from Fort Mott in Pennsville, N.J. One set of quarters was floated over the year prior. From 1934 until 1936, Fort DuPont and the 1st Engineer Regiment were commanded by Col. Ulysses S. Grant III, grandson of President Ulysses S. Grant. Some sources state the two 3-inch (76 mm) guns of Battery Elder were relocated to "Delaware Beach" in 1922 (location unclear), and in 1942 further relocated to Reedy Island to protect a US Navy defensive boom as Battery Liston or Battery Elder II, reportedly leaving service later that year.[9][3]

World War II

[edit]

November 1943

During World War II Fort DuPont served as a mobilization station for deploying units. In 1941, following re-designation, the 1st Engineer Battalion departed for overseas service. At the war's start, the post was the headquarters for the Harbor Defenses of the Delaware, with garrison units including the 21st Coast Artillery Regiment, 261st Coast Artillery Battalion, and the 122nd Separate Coast Artillery (Anti-Aircraft) Battalion.[17][18][19][20] In 1942, the headquarters for HD Delaware was transferred, along with artillery troops, to Fort Miles in Lewes, Delaware. Fort DuPont was disarmed with all weapons scrapped by this time, as Fort Miles had superseded the previous defenses of the Delaware.[10] Col. George Ruhlen was post commander from 1940 until 1944, and following retirement was succeeded by Col. Randolph Russell. In May 1944, the 1231st SCU prisoner-of-war camp was established using repurposed temporary buildings in the mobilization area.[21][22] During the war, roughly 3,000 German POWs were housed at Fort DuPont. These POWs included crew members of the submarine U-858 that surrendered off the coast of Lewes, Delaware along with the rest of German forces in May 1945. POWs worked as dishwashers, waiters, grocers, butchers, and other support roles on post as well as working on other local installations such as the New Castle Army Air Base. German POWs worked for civilian canneries, garbage companies and repaired sections of the boardwalk for the city of Rehoboth Beach. Following the war, effective December 31, 1945, Fort DuPont was placed "in the category of surplus" according to AG 602 (dated October 5, 1945) issued by the federal government.

After World War II

[edit]In 1948, the post reopened as the Governor Bacon Health Center[23] operated by the Delaware Division of Health and Social Services. In 1992, a large portion was rededicated as Fort DuPont State Park. In 1976, the Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Scannell Armory (named in 1992) was built on the site of the former POW camp. In 1996, this armory became the home station for the 153rd Military Police Company, a unit in the Delaware Army National Guard.[24] Fort DuPont was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999.[25] The Fort DuPont Historic District comprises roughly 350 acres and over 75 buildings, structures, and objects.[26]

Restoration and preservation

[edit]During WWII, about 300 buildings and structures lined the streets of Fort DuPont. By 2011, less than 80 historic buildings and structures remained.[27] In 1947, temporary mobilization barracks were torn down by the state prior to the opening of the health center. The mobilization hospital complex, recreation hall, and chapel were integrated into the health center's master plan. Today, only the chapel and one hospital building survive. The others have collapsed and were torn down. Most of the quarters on officers row were cannibalized and demolished by 1980. Sections of Fort DuPont are governed by six different state agencies, which often leads to confusion over who is responsible for maintaining specific roads, buildings, and structures. Since the health center downsized in the late 1970s, state funding is limited and doesn't allot for basic maintenance and care of the buildings. Houses built in the 1890s to 1900s are plagued by collapsed chimneys, damaged roofs, broken windows, rotting porches, and in desperate need of a simple coat of paint. The twenty-gun battery is barely visible in summer months due to reclamation by invasive species of vegetation. According to the Natural Lands Trust, most buildings/structures are at a point where they can be stabilized but waiting any longer could prove detrimental.[28] In 2011, the State of Delaware approved a $250,000 bond bill that will fund the creation of a master plan, which will focus on restoration, preservation, and adapting historic structures for modern use.

Resident curatorship program

[edit]

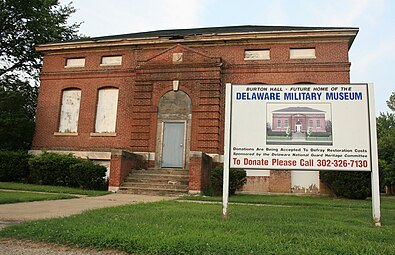

Currently, Delaware State Parks offers a resident curatorship program, which is an "opportunity for a public/private partnership in which the curator (which may be a couple) donates their own resources—time and/or money—to the restoration of an historic property in exchange for a long-term no-rent agreement. Because the cost to the curator is often much more than $100,000, the term of the lease is typically for the life of the curator(s)".[29] Almost a dozen historic properties on Fort DuPont are available for residency as part of this curatorship program. There are also several buildings/structures that are available under a similar program zoned for regular businesses and non-profit organizations. In 2006, the Fort Delaware Society became the first successful curator following the adaptive reuse of the quartermaster office (Building 113) on Staff Lane. Since then, the Delaware Military Heritage & Education Foundation has signed on with the program, pledging to restore the Post Exchange & gymnasium (Building 36) and a non-commissioned officer duplex (Building 91), both for use as part of the Delaware Military Museum. In 2007, the post movie theater's very existence was threatened by years of neglect.[30] State funding was scarce, due to the economy, but enough money was allocated to provide the 398-seat theater with a new roof, drains and gutters, stabilized marque, and minor window repair. In 2007, The News Journal published an article citing the theater's availability in the curatorship program. Delaware State Parks' historian, Lee Jennings said it would be "the perfect place for the community to gather..." and watch plays, musicals, vintage films, as well as modern movies.

Adaptive reuse

[edit]Although not part of the curatorship program, almost a dozen historic buildings are currently under adaptive reuse status. The Renewal Center (non-denominational) operates out of the post chapel (Building T-213), which was built in 1941. The center, which maintains and cares for the building, has a lease through the Delaware Division of Health and Social Services (DHSS).

The Delaware Wing of the Civil Air Patrol is headquartered out of the old post headquarters (Building 10) and has lease for the property through the Delaware Division of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC). The double-company barracks (Building 49) and band barracks (Building 48) serve as the main hospital buildings for the Governor Bacon Health Center (DHSS) at Fort DuPont. In fact, several other historic structures still serve their original purpose, including the carpenter shop (Building 61) and other maintenance buildings, which are utilized by DHSS.

The Delaware Division of Purchasing operates a surplus warehouse in the original commissary (Building 43), and the state's fleet vehicles are housed and maintained in the original motor pool. In 2008, Delaware State Parks (part of DNREC) restored one of the brick duplexes (Building 90), which according to Lee Jennings, will eventually contain 1930s furnishings and serve as a location for public programming.

Leisure

[edit]Fort DuPont State Park contains the home field of the Diamond State Base Ball Club, a vintage base ball team. The Diamond State Base Ball Club typically plays 4-6 games there per year. The Diamond State Base Ball Club also plays at least once per year at Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island and also at nearby Port Penn, Delaware. The Diamond State Base Ball Club is a non-profit amateur organization created for the purposes of providing physical fitness to its members, and educating the public on the history of baseball and local history.

See also

[edit]- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- Harbor Defense Command

- List of coastal fortifications of the United States

Gallery

[edit]-

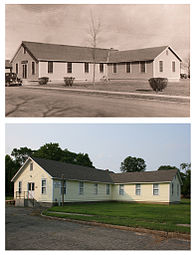

Noncommissioned Officer Duplex

-

Mine Control Casemate

-

War Department Theatre

-

Then: Quartermaster Office (Building 113)

Now: Fort Delaware Society Headquarters -

Post Exchange (Building 36)

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Fort Delaware Society". Fortdelaware.org. 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ a b c d Harbor Defenses of the Delaware at American Forts Network

- ^ Ames, David L., Dean A. Doerrfield, Allison W. Elterich, Caroline C. Fisher, and Rebecca J. Siders. Fort DuPont, Delaware: An Architectural Survey and Evaluation. Newark, DE: University of Delaware, Center of Historic Architecture and Engineering, 1994.

- ^ J., Siders (Sheppard), Rebecca; Anna, Andrzejewski (8 March 1999). "Fort Dupont Historic District". Retrieved 9 June 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Historic Fort Dupont Complex Redevelopment - Background" (PDF). Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Fort Dupont Historic District: Delaware City, Delaware Historical Places". Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Crumrine, Bishop. "Letters Sent 1862–1865." Washington and Jefferson College, U. Grant Miller Library, January 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f Fort DuPont at FortWiki.com

- ^ a b Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- ^ The Harbor Defenses of the Delaware at CDSG.org

- ^ Gaines, William C. "The Coastal and Harbor Defenses of the Delaware, Part III." The Coast Defense Journal, vol. 10, no. 2 (May 1996): 19-72.

- ^ Coast Artillery Organization: A Brief Overview at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ^ Gaines, William C.

- ^ Rinaldi, Richard A. (2004). The U. S. Army in World War I: Orders of Battle. General Data LLC. p. 151. ISBN 0-9720296-4-8.

- ^ Map of HD Delaware at FortWiki.com

- ^ Santeramo, Ralph J., My Years in the United States Army: January 25, 1941-December 8, 1945. San Diego, CA: Ralph J. Santeramo, 2006.

- ^ Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, 1917-1950, Regular Army regiments, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2, p. 14

- ^ Gaines, William C., Historical Sketches Coast Artillery Regiments 1917-1950, National Guard Army Regiments 197-265, 261st Coast Artillery entry

- ^ Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. pp. 459, 472, 487, 492. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.

- ^ Heimer, Harry. "Hits and Bits of the 1265th."Fort DuPont Flashes, May 1944: 5-8.

- ^ Trsisnar, Irena. "Leopold Gosnik: A Prisoner of War at Fort DuPont, 1944–1945," Fort Delaware Notes, vol. 58 (2007): 18-26.

- ^ "Fort DuPont State Park, Delaware City, Delaware". Destateparks.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "722nd Troop Command, 153rd MP Company (CS)". Delaware National Guard. 2011-04-07. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Fort Dupont Historic District". Dspace.udel.edu:8080. 1999-03-08. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "National Register of Historical Places - DELAWARE (DE), New Castle County". Nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Ames, David L., et al.

- ^ Williamson, Peter, D. Andrew Pitz, Richard Sprenkle, and Steven Kuter.Conceptual Master Plan: Fort DuPont State Park, Delaware City, Delaware. Media, PA: Natural Lands Trust, 1995.

- ^ "Resident Curatorship Program". Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ Frank, William P. "Weeds, Three Boys Playing Soldier Take Over at Forgotten Fort DuPont." Wilmington Morning News, June 28, 1957: 33.

Further reading

[edit]- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

External links

[edit]- Fort DuPont State Park

- Map of HD Delaware at FortWiki.com

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- Fort Delaware Society

- Images of America: Fort DuPont

- Delaware Military Heritage & Education Foundation

- 153rd Military Police Company

- 1864 establishments in Delaware

- Delaware City, Delaware

- American Civil War forts

- Forts in Delaware

- Delaware in the American Civil War

- Buildings and structures in New Castle County, Delaware

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Delaware

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Delaware

- National Register of Historic Places in New Castle County, Delaware

- State parks of Delaware

- Protected areas established in 1992

- Parks in New Castle County, Delaware

- 1992 establishments in Delaware