Florida red-bellied cooter

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2011) |

| Florida red-bellied cooter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Pseudemys |

| Species: | P. nelsoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudemys nelsoni Carr, 1938

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

The Florida red-bellied cooter or Florida redbelly turtle (Pseudemys nelsoni) is a species of turtle in the family Emydidae.

Etymology

[edit]The specific name, nelsoni, is in honor of American biologist George Nelson (born 1873).[3]

Geographic range

[edit]P. nelsoni is native to Florida, and southern Georgia. Fossils of P. nelsoni have also been found along the coast of South Carolina from the Pleistocene Epoch, indicating that the historic range of this species used to extend farther north. Today, its northern counterpart, the Northern Red-bellied Cooter (Psuedemys rubriventris) occupies this region.[4]

Biology

[edit]The Florida red-bellied cooter is mainly herbivorous, and can be found in nearly any type of aquatic habitat. It feeds on a variety of aquatic plants including waterweed (Vallisneria and Elodea), duckweed (Lemna and Wolffia), and arrowhead (Sagittaria) species.[5] It has been documented consuming algae as well. Juveniles tend to primarily consume small insects. As juveniles age, they transition to a plant-dominated diet.[6] It reaches particularly high densities in spring runs, and occasionally can be found in brackish water. It appears to have an intermediate salinity tolerance compared to true freshwater forms and the highly specialized terrapin (Malachemys).[7] This species is active year-round and spends a large portion of the day basking on logs. It is noted for sometimes laying its eggs in the nest mounds of alligators. Sex is temperature-dependent with males being born at cooler temperatures and females being born at warmer temperatures with a pivotal temperature of about 28.5 °C (83.3 °F).[8] The Florida red-bellied cooter is closely related to the Peninsula cooter (Pseudemys floridana) and can often be found basking on logs together.

Description

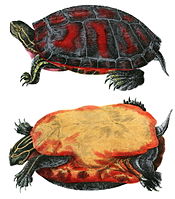

[edit]The Florida red-bellied cooter can be distinguished from other similar turtles by its distinctive red-tinged plastron (belly) and two cusps (like teeth) on its upper beak. Like most turtles of the genus Pseudemys, this species is a fairly large river turtle. Straight-line carapace length in mature turtles can range from 20.3 to 37.5 cm (8.0 to 14.8 in).[9] Females, which average 30.5 cm (12.0 in) in carapace length and weigh 4 kg (8.8 lb), are noticeably larger than males, which are around 25 cm (9.8 in) and 1.8 kg (4.0 lb) in mass.[1][10]

Export

[edit]The Florida red-bellied cooter is commonly exported for consumption and the pet trade, with about 50% wild caught individuals and 50% captive bred.

Most of US export statistics (as collected by the World Chelonian Trust in 2002–2005) simply describe exported turtles by the genus, Pseudemys, without identifying the species. They are exported by the million, and are mostly farm-raised.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Pseudemys nelsoni ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170495A97426506. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T170495A6782280.en. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 195. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Pseudemys nelsoni, pp. 188-189).

- ^ Ehret, Dana J.; Atkinson, Benjamin K. (September 2012). "The Fossil Record of the Diamond-backed Terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin (Testudines: Emydidae)". Journal of Herpetology. 46 (3): 351–355. doi:10.1670/11-085. ISSN 0022-1511. S2CID 86826329.

- ^ Jackson, Dale (2010-08-07), "Pseudemys nelsoni Carr 1938 – Florida Red-Bellied Turtle", Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises, Chelonian Research Foundation, pp. 041.1–041.8, doi:10.3854/crm.5.041.nelsoni.v1.2010, ISBN 978-0965354097

- ^ Pseudemys nelsoni (Florida Redbelly Turtle). Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pseudemys_nelsoni/

- ^ Dunson, William A.; Seidel, Michael E. (June 1986). "Salinity Tolerance of Estuarine and Insular Emydid Turtles (Pseudemys nelsoni and Trachemys decussata)". Journal of Herpetology. 20 (2): 237. doi:10.2307/1563949. JSTOR 1563949.

- ^ Valenzuela, Nicole; Valentine, Lance, eds. (2018-06-13). Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Vertebrates. Open Monographs. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. doi:10.5479/si.9781944466213. ISBN 978-1-944466-21-3. S2CID 83448966.

- ^ "Species Profile: Florida Redbelly Turtle (Pseudemys nelsoni) | SREL Herpetology".

- ^ "BREEDING TURTLES - Pseudemys nelsoni ".

- ^ Declared Turtle Trade From the United States - Pseudemys sp.

External links

[edit]- Florida red-bellied cooter Southeast Ecological Science Center.

Further reading

[edit]- Carr AF (1938). "Pseudemys nelsoni, a New Turtle from Florida". Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 8: 305–310. (Pseudemys nelsoni, new species).

- Ernst CH, Barbour RW, Lovich JE (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington, District of Columbia: Smithsonian Institution Press. 578 pp.

- Hubbs C (1995). "Springs and Spring Runs as Unique Aquatic Systems". Copeia 1995 (4): 989–991.

- Reed RN, Gibbons JW (2004). "Conservation status of live U.S. nonmarine turtles in domestic and international trade – a report to U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". Aiken, South Carolina: Savannah River Ecology Lab. 92 pp.