Florence Bravo

Florence Bravo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Florence Campbell 5 September 1845 Darlinghurst, Colony of New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 17 September 1878 (aged 33) |

| Other names | Florence Ricardo Florence Turner |

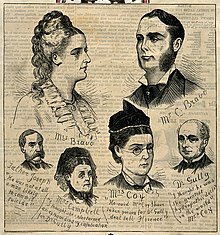

Florence Bravo (née Campbell; 5 September 1845 – 17 September 1878), previously known as Florence Ricardo, was an Australian-born British heiress and widow who was linked to the unsolved murder of her second husband, Charles Bravo. On 21 April 1876, after three days of agonising illness, Charles died of antimony poisoning. Although there was widespread innuendo in the press about Florence's role his death, she was never indicted and the case never reached the courts due to lack of evidence.[1][2]

During the Coroner's inquest, the lurid details of Florence's past affair with Dr James Manby Gully, a married man thirty-seven years her senior, became a topic of intense fascination, covered by newspapers ranging from The Times and The Daily Telegraph to The Illustrated Police News,[1][3] as well as publications overseas.[4]: 93

Florence had previously inherited £40,000 after her first husband, Alexander Ricardo, an alcoholic who drank himself to death. Florence herself lived for only two years after Charles' death and died at the age of 33.

Early life and family

[edit]Florence Bravo was born Florience Campbell on 5 September 1845 in the settlement of Darlinghurst in what was then the Colony of New South Wales. She was the eldest daughter of land speculator, merchant and future politician Robert "Tertius" Campbell and his wife Ann (née Orr).[5][4]: 10 Florence's father had made a considerable fortune buying and selling gold.[6][7] The family's affluence them to move with their eight children, a governess and three servants to England in 1852.[7] In 1859 Robert purchased Buscot Park, a large estate near Faringdon and historically in Berkshire; he also had homes in Belgravia and Brighton.[8][4] Whilst growing up in England, Florence took elocution lessons, learned French and some German and did needlework.[8][4]: 11 She was very fond of animals, especially horses.[4]: 10

As a teenager, Florence traveled with her family to Canada, where she met Alexander Ricardo, a young British military officer stationed at the Royal Military College.[8] Ricardo was the grandnephew of economist David Ricardo; the only son of International Telegraph Company founder John L. Ricardo, who had served as Member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent; and the nephew of James Duff, the Fifth Earl of Fife, through his mother, Lady Catherine.[8][4]

First marriage

[edit]

On 21 September 1864, at the age of nineteen, Florence married Ricardo at Buscot Park, following a brief courtship.[8] Newspapers hailed their marriage as "the union of two great families of Europe" – the Campbells, who had been landowners of Scottish descent, and the Ricardos, descendants of a prominent Dutch Jewish family.[4]: 11 Their lavish wedding was officiated by the local vicar, as well as Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford.[7][4] Florence received a generous marriage settlement of £1,000 a year from her father.[4][a] After a honeymoon in the Rhineland, the couple returned to England and lived in the West Country.[4]

Problems

[edit]Seven months into their marriage, Florence informed her father that she and Ricardo were having problems.[4] They were at odds over Ricardo's military career with the Grenadier Guards; she wanted to have a large family, and feared that he would be sent to war and killed in conflict.[4]: 11–12 Florence finally prevailed, and in the spring of 1868 Ricardo received an honourable discharge and left the service with the rank of captain.[9][4]: 12 The couple moved to Gatcombe Park in Gloucestershire, where they took part in aristocratic pursuits such as hunting, fishing and horseriding, and regularly hosted parties.[4] Ricardo tried to get involved in their families' businesses, but quickly lost interest and grew depressed.[4]

Florence soon found out about Ricardo's infidelity.[4] He had a mistress who lived in the West End of London, and had been seen with women in hotels in Sussex and in the West Country.[4] When confronted, Ricardo eventually confessed, but persisted with his extramarital affairs.[4] He became an alcoholic, and his health started to deteriorate.[9] When drunk, he was verbally abusive and at times violent toward Florence.[9][4]: 13 Florence herself became ill and eventually found herself on the verge of a nervous breakdown.[4]: 14 In late 1869 she wrote to her mother that she wanted a separation from Ricardo,[8] but her father regarded the failure of their marriage as "morally offensive";[4] both parents were determined to avoid the scandal that would result.[8]

Treatment by Dr Gully

[edit]

As an alternative to separation, Florence's mother advised the couple to visit the spa town of Malvern, where their family friend Dr James Gully, a homeopathic hydrotherapist, had been successfully treating Victorian celebrity patients including Benjamin Disraeli, Charles Darwin, Alfred Tennyson and Florence Nightingale.[8] In 1870, Florence became the patient of 62-year-old Dr Gully, who had once treated her for a throat infection when she was aged 12.[9][4]: 16 To the alarm of her parents, Gully recommended that Florence separate from her husband for the sake of her own health and wellbeing.[8] She went ahead with the separation, with help from Gully, despite her father's threat to cut her off financially.[8][10]: 32

Death of Alexander Ricardo

[edit]Ricardo made a final attempt to reconcile with Florence before the separation papers were finalised in March 1871,[10]: 31 and decided to go abroad after she refused.[4]: 17–18 Several weeks later, on 20 April 1871, Florence received a telegram from London saying that Ricardo had been found dead in Cologne, Germany,[4]: 22 in lodgings he shared with a "female companion."[8] The cause of death was haematemesis, triggered by a final alcohol binge.[8][4] Because Ricardo had neglected to change his will, Florence inherited a fortune of £40,000.[8][4]

Affair with doctor

[edit]

In the years that followed, Florence and Gully had an affair which they tried to keep secret, while maintaining the outward appearance of propriety.[4]: 20–22 Florence's parents disapproved of her "infatuation" with Gully and insisted that she cut all ties with him.[10]: 33–34 Florence refused and became estranged from them, but because of the inheritance from her late husband, she was now independently wealthy.[4] Florence later admitted that she and Gully had had "conversations about marriage."[8] Although Gully was technically married, he had been separated from his wife, who was seventeen years his senior, for thirty years.[8] Gully promised to marry Florence after his wife died, to avoid scandal, and planned to move with her abroad.[4]

Florence moved to South London and leased a large mansion called The Priory in Balham, where she could keep two horses and a garden.[4]: 137 Gully retired and leased a house called Orwell Lodge, which was a five-minute walk away.[8][4] According to their servants, Florence and Gully frequently visited each other, went shopping and went riding, but never spent the night together.[8]

Author James Ruddick states, however, that the relationship was exposed in May 1872 when Florence was invited to stay at the family home of her solicitor, Henry Brookes, in Surrey.[4]: 27 Mr and Mrs Brookes returned home from a walk to pick up an umbrella, when they discovered Florence and Gully having sex in their drawing room.[4] A heated exchange ensued, overheard by the servants, and their relationship quickly became the subject of widespread gossip.[4] Gully instructed his solicitor to sue Mrs Brookes for slander, but soon withdrew the instruction.[4] The social consequences were devastating to Florence: two servants threatened to quit, some grocers refused to serve her staff and the invitations she sent out for afternoon tea and dinner were returned without explanation.[4]: 28 Within a week, the news had reached Florence's parents in Buscot Park.[4] According to Alison Harris, a descendant of Florence's eldest brother William, her father was "incensed and outraged" but also "broken" by the scandal.[4] Florence's telegrams to her parents and her letters to her sister Edith went unanswered.[4]

Abortion

[edit]In 1873, Florence traveled with Gully to Bad Kissingen, a spa town in rural Bavaria.[10]: 41 Later, she discovered she was pregnant.[10] Fearing further scandal, Florence allowed Gully to perform an abortion, which went badly.[4][b] She became seriously ill, and later stated that Jane Cannon Cox, her "lady's companion", had saved her life by attending to her around the clock for six days and six nights.[4] The ordeal effectively ended Florence's affair with Gully.[4][11] She refused to see him for two weeks, ended their physical relationship and started to distance herself.[4][9] Weary of social ostracism and longing for reconciliation with her parents, Florence started to seek a way out of the relationship.[9][8]

Friendship with Jane Cox

[edit]When she was moving into the Priory, Florence had decided to hire Cox to oversee day-to-day management of the household, including her large staff.[4]: 24 Cox was a widow who had lived in Jamaica and returned to England with her three young sons after the death of her husband.[4]: 25 Florence said she was "very impressed by her, particularly her kindness and her excellent manners."[4] According to author James Ruddick:

Neighbours in Balham would later recall the sight of Florence and Mrs Cox travelling together in their open-top carriage, and comment on the attraction of opposites: Florence, the beautiful young widow, with her jewellery and flowing hair; Mrs Cox, the small, shy woman, draped in black, with the hardness and the sheen of a strange insect.[4]: 26

By all accounts, Florence and Cox grew very close. During this period when Florence was cut off from her family—and from society—Cox became a maternal figure and confidante.[4]: 26–27 Florence later stated, "I called her Janie and she called me Florrie. At one time she was my only friend."[4]

Second marriage

[edit]

In 1874, Cox engineered a series of "accidental" meetings between Florence and Charles Bravo in Kensington, where he lived with his parents, and in Brighton.[4]: 33–34 Charles was the stepson of Joseph Bravo, a business associate of Cox's late husband, and the same age as Florence.[8][4] Educated at King's College London and Trinity College at Oxford University, Charles had been admitted to the bar as a barrister in 1870.[8] His friendship with Florence quickly blossomed, and although she joked to her mother that his letters were "cold and undemonstrative" and that he wrote "tersely, as all barristers do,"[8] he wrote to her regularly and not without affection.[4]: 35

In October 1875, Charles proposed marriage.[4] For Florence, this prospect offered the chance to restore her respectability in society.[11] She wrote a letter to Gully from Brighton that their relationship had to end because she wanted to reconcile with her family.[8][4]: 36 Gully went to Brighton, where they met in a hotel dining room, and Florence admitted that she was expecting a marriage proposal from Charles.[10]: 51–52 In November 1875, she told Charles about her past affair with Gully, knowing that she risked rejection.[10]: 61–62 According to Florence, after some thought, Charles said she "had acted nobly and generously in telling him" and that her confession made him "more certain" that it was unlikely she would "err" again.[10]: 52 The following day, Charles confessed to Florence that he had also had an affair for four years with a mistress in Maidenhead, who had a daughter by him.[10] They agreed not to mention their past affairs to each other ever again.[10]

On 7 December 1875, Florence and Charles were married at All Saints Church in Kensington.[4]: 41 Charles' main motivation for marrying Florence, despite her chequered past and against the wishes of his mother,[8] was financial.[11][9][10] Prior to the wedding she had decided to retain control over her fortune rather than have it transfer to her new husband, a legal option that had become available after Parliament had passed the Married Women's Property Act of 1870.[11] Upon finding out, Charles threatened to call the wedding off, saying to Brookes, "Damn your congratulations! I've come about the money!"[10] He urged Florence's father to intervene, writing in a letter: "I cannot contemplate a marriage that does not make me master in my own house. I cannot sit upon a chair or eat from a table which does not belong to me."[4]: 40 Florence was so upset by Charles' behaviour that she sought advice from Gully, who "advised her not to squabble about the furniture" and wished her happiness.[10]: 69 Florence ultimately agreed to a compromise: she would allow Charles to take over the lease to the Priory, as well as all furnishings, and put him in her will, while she retained control of her money.[4]

By all accounts, during the first month of their marriage, the new couple seemed genuinely happy.[8][4]: 45 After a brief honeymoon in Brighton, they returned to London.[4] In letters to their parents, they described going riding together, playing lawn tennis, going into town and entertaining relatives and friends, including "local aristocrats."[8] Florence planned a Christmas party with thirty-one invited guests, including the mayor of Streatham.[4] That Christmas, she apologised to her parents for all the pain she had caused.[4]: 46 On 9 January, she sent them a telegram informing them she was pregnant.[4] Charles jokingly referred to the baby as "Charles the Second".[4]

Problems

[edit]By February 1876, it was clear that a power struggle had developed within the marriage.[4][11] Charles was particularly critical of Florence's extravagance, often saying that his mother disapproved.[10]: 78 Florence had a butler, a footman, a "lady's maid", two housemaids, a cook, a kitchenmaid, three gardeners, a coachman, a groom and a stable boy, in addition to Cox.[10] Two weeks before the wedding, Charles fired George Griffiths, Florence's coachman of four years.[4]: 44 Once they were married, Charles pressured Florence to curb expenses, saying that he would fire her "lady's maid" and transfer her duties to another maid, Mary Ann Keeber; dismiss one of the gardeners; landscape the flower beds so they could fire yet another gardener; and sell her horses.[4]: 48 Florence later stated, "I told him that he had no right to interfere in my arrangements...I reminded him that I had always lived within my means – and I was accustomed to looking after my own affairs."[4] Charles then became agitated and lost his temper—the first of many heated arguments between the couple.[4]

Charles also developed a jealous "obsession" with Gully, who continued to live nearby,[4]: 51–52 despite Florence's offer to buy out his lease.[10]: 53 In December 1875 and January 1876, Charles received three anonymous letters, all in the same handwriting, accusing him of marrying Florence for her money and referring to her as Gully's mistress.[4][10]: 73 Although Cox told him that the handwriting did not appear to be Gully's,[10] Charles made up his mind that it was and started reprimanding Florence for her past relationship, constantly questioning whether she was going to see him and saying that he wanted to "annihilate" Gully.[4]

Florence left the Priory to stay at Buscot Park, complaining to her parents about Charles' "violent ebullitions of temper" and saying that his "meanness disgusted her."[4]: 51 Charles sent her a series of apologetic letters, begging her to return home and promising, "If you come back, I will so take care of you that you will never leave me again."[10]: 82–83 During her absence, however, staff at the Priory reported that Charles had called Florence "a selfish pig" who had been spoilt all her life and that, as her husband, he was right to stand up to her.[4]: 54 According to Ruddick, Charles also took the opportunity to tell Cox that he was dismissing her, but would give her enough time to find a new position.[4]: 56 Although he was grateful to Cox for bringing them together, Charles was jealous of her closeness with, and influence over, Florence, and had wanted to fire her for some time to reduce expenses.[4]: 54–55

Miscarriages

[edit]Sadly, shortly after returning to Balham, Florence suffered a miscarriage.[4]: 57 She became very weak, was bedridden and grew depressed.[4]: 58–59 After her doctor recommended "a change of air", Florence planned a holiday in Worthing, but Charles and his mother opposed the trip due to the expense.[10]: 84 When Florence said she would confront his mother for interfering, Charles lost his temper, shouting, "I will go and cut my throat!"[10] He then struck Florence and stormed off.[10] In March, Charles told Florence that he felt it was time for her to get pregnant again.[4]: 61 By then she doubted whether she would be able to carry a child to term, but a few weeks later she telegraphed her parents to inform them that she was pregnant for a second time.[4]: 62–63 As she had feared, the second pregnancy also ended in miscarriage on 6 April 1876.[9][10]: 96 Considerably weakened, she planned once more to travel to Worthing to rest and recover.[4]: 66

Death of Charles Bravo

[edit]

Charles died less than five months after marrying Florence.[4]: 41 On 18 April 1876, he and Florence went into town together, briefly quarrelling when their carriage passed Orwell Lodge.[10]: 115 They stopped at the bank and at the jewellers on Bond Street before going their separate ways.[10]: 116 Florence went shopping on Haymarket and bought hair lotion and premium tobacco for Charles as a "peace offering."[10] Charles went to the Turkish bath at 76 Jermyn Street and met Florence's uncle, James Orr, for lunch at St James's Hall.[10]: 116, 143

Florence was resting in the morning room when Charles returned to the Priory.[10]: 116 He decided to go riding, ignoring the groom's warning not to take any of the horses out since they had already exercised that day.[4]: 66–67 The horse then bolted for four miles, taking Charles on a long and unpleasant ride.[8] When he returned, Charles was stiff and exhausted.[10]: 117 According to the butler, Frederick Rowe, Charles was "in great pain" and looked "exceedingly pale"; Florence said she had to help him to his feet when his bath was ready.[10]

At dinner, Charles was extremely irritable toward both Florence and Cox, complaining that he was sore from the horse ride and that a previous toothache had returned.[4] During the meal, Charles was angered to receive a letter from Joseph Bravo criticising him for playing the stock market; his stepfather had opened a letter from Charles' stockbroker showing that he had sold shares at a loss.[10]: 118–120 Before going to bed, Charles went into Florence's bedroom to scold her in French for drinking too much that day, as she had since the miscarriage; she had had champagne at lunch, a bottle of sherry at dinner and had asked for two glasses of wine upstairs.[4]: 67

After Florence had fallen asleep, Charles suddenly burst out of his bedroom, shouting, "Florence! Florence! Hot water!"[8][4]: 69 The maid, Mary Ann Keeber, was halfway down the stairs, waited for Florence to emerge, went back up the stairs, knocked on Florence's bedroom door and alerted Cox .[4]: 70–71 Cox ran to the other bedroom and found Charles vomiting out the window.[10]: 123 He fainted, but Cox stayed with him and rubbed his chest, sending Mary Ann downstairs for mustard and hot water.[10] They poured it down Charles' throat, which caused him to vomit again, but he remained unconscious.[4]: 71 Cox told Mary Ann to tell the butler to send the coachman out to Streatham for Dr George Harrison.[10]: 124 Mary Ann then woke Florence, who got up saying, "What's the matter? What's the matter?"[10] Alarmed to see Charles not moving, Florence held his hand, sobbing, and asked whether a doctor had been sent for.[10]: 125 When Cox replied that she had sent for Harrison, Florence was "horrified" and screamed for Rowe to get another doctor—any doctor—who was closer.[10]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Leading up to his death on 21 April 1876, Charles was seen by six medical professionals, including one of the most highly regarded physicians in England.[10]: xvi, 66 The first two doctors were Dr Joseph Moore of Balham, who arrived first, and Dr George Harrison of Streatham, who arrived after midnight.[4]: 73 Moore and Harrison conferred and agreed that Charles had been the victim of a serious case of poisoning and would soon die.[4]: 74 They asked Florence, Cox and Mary Ann if they had any idea what could have caused his symptoms. Florence suggested that Charles had had a heart attack after the horse ride, and also mentioned that he was "prone to fainting fits" and that he had been "worried about stocks and shares."[4] Harrison told Cox that she was wrong when she suggested that Charles had ingested chloroform, and that the symptoms had likely been caused by arsenic, to which Florence responded, "Arsenic?"[4]: 75 When he asked if there was any poison in the house, Florence answered, "Only rat poison, in the stables."[4] She also stated that Charles had no reason to take poison.[4]

Florence suggested sending for Royes Bell, Charles' cousin and best friend, who was an assistant surgeon at King's College Hospital in London, with his own practice on Harley Street.[12][4]: 75 Bell brought with him his superior, Dr George Johnson, who would later become vice-president of the Royal College of Physicians.[13][4]: 75 Johnson, in turn, brought in Henry Smith, another assistant surgeon at King's College Hospital and an in-law of Charles' mother.[14][10]: 142 Charles awoke after Bell arrived, and upon questioning insisted to Bell and Johnson that the only substance he may have swallowed was laudanum, which he had rubbed onto his own gums to treat his toothache.[10]: 131–133 Cox took Bell aside and told him that before he fainted, Charles had said, "I have taken poison – don't tell Florence."[4]: 78 She repeated the claim in front of Johnson and Harrison; Johnson asked if it was true, but Charles said he did not remember mentioning poison.[4][10]: 132 Florence telegraphed Charles' parents to come at once.[4]: 80 Her father-in-law, Joseph Bravo, later stated that Florence "did not seem much grieved" and that she gave contradictory explanations for his condition.[4] She told Charles' former nanny that she thought it was food poisoning from lunch, while she said to Bell that what had happened to Charles would "always remain a mystery."[8][4]: 81

Finally, Florence wrote to Sir William Gull, a "leading English physician of his time",[15] and requested that he see her husband who was "dangerously ill."[10]: 142–143 Gull had become famous for saving the life of the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) by diagnosing and treating typhoid.[10][16] Florence later explained, "I believed that if anyone could save Charles, it was Sir William. I knew that he had saved people when others had given up all hope for them."[4]: 81 Gull knew her father "very well as a patient and an acquaintance";[10]: 200 they had dined together at the Reform Club.[4]: 82 After examining Charles, Gull told Florence that nothing could be done to save his life.[10]: 147 He pushed Charles repeatedly to reveal the name of the poison he had taken, but until the end, Charles insisted that he had only applied laudanum in his mouth, on his lower jaw, for neuralgia.[4]: 82–83

In his final hours, Florence offered to send for the rector of Streatham, but Charles declined.[4]: 83 Instead, he recited the Lord's Prayer with his family.[8] To Florence, he said, "Make no fuss when you bury me."[4] He made a will favourable to Florence, witnessed by his cousin Bell and the butler Rowe.[4] To his mother, he said, "Take care of my poor, dear wife."[8] Charles was pronounced dead by Bell at 5:20 am, fifty-five hours after he had collapsed.[4]: 84

Investigation

[edit]First inquest

[edit]The first coroner's inquest into Charles' death took place on 25 and 28 April 1876.[10]: 150, 155 Impressed by the credentials of the many doctors and surgeons who had examined him, the Coroner for East Surrey, William Carter, stated that the cause of death was likely suicide and sought to "spare the feelings of the family" by keeping the inquiry private, perfunctory and not calling Florence as a witness.[10]: 150, 158 Carter accepted Florence's request, written by Cox at the request of Florence's father-in-law, to hold the inquest at the Priory, where she would provide refreshments—a practice which was not unusual at the time.[10]: 151 The post mortem concluded that Charles had ingested thirty to forty grains—ten times the lethal dose—of tartar emetic, a derivative of antimony.[4]: 86 Based on the evidence and testimony of the witnesses, the jury returned an open verdict, stating that there was "not sufficient evidence under what circumstances" the antimony had "entered his body".[10]: 158

Escalation

[edit]Friends and family of Charles objected to the implication that he had committed suicide, saying he had been "in his usual health and spirits."[10]: 158 Troubled with how the inquest was handled, Barrister Carlyle Willoughby, a friend and colleague of Charles, contacted Scotland Yard to voice his concerns.[10]: 160 Charles' father-in-law also spoke to the Metropolitan Police, and hired criminal lawyer George Lewis.[10]: 160–161 Detective Chief Inspector George Clarke was assigned to investigate.[4]: 85 On 8 May 1876, Florence, who was staying in Brighton, consented to Clarke's search of the Priory.[10]: 171

On 11 May 1876, The Daily Telegraph first brought national attention to the mystery surrounding Charles' death, denouncing the inquest as having been conducted in a "secret and unsatisfactory manner."[17][10]: 168 The sensational article named some of the doctors, gave details about the dinner menu on the night of Charles' death and speculated that the Burgundy wine which he alone had drunk had been poisoned.[10]: 168–169 On the advice of the Buscot Park physician and her father, for one week, Florence had her solicitor advertise a reward of £500 for anyone who could produce evidence of selling antimony to a member of the Priory household staff.[10]: 171 At first, suspicion fell on Griffiths, the coachman fired by Charles, who had reportedly shouted in a pub that "Mr Bravo would be dead in five months."[10]: 169 Police found that a large quantity of tartar emetic had been sold by a chemist in Streatham to Griffiths in the summer of 1875, which he used on horses to eliminate worms and stored in the Priory's stables.[4]: 88–89 However, press interest in Griffiths subsided after it turned out he had moved to Kent and was not in the area when Charles was poisoned.[10]: 169

Newspapers were soon filled with gossip about Florence's past affair with Gully and recent sightings of Gully together with Cox, as well as rumours that Cox had been fired, thus providing a motive.[10]: 169–170 The accounts of Harrison and Moore were published in the Telegraph, while Johnson shared his perspective in The Lancet, noting that Cox had initially claimed that Charles admitted to swallowing poison before fainting—a claim which Charles himself questioned when he woke up.[10]: 170 On 18 May 1876, Serjean Simon, MP, asked Home Secretary R. A. Cross in the House of Commons whether he was aware of the "unsatisfactory" nature of the coroner's inquest into Charles' death.[10] Increasingly, suspicions were raised both publicly and privately about Cox.[10]: 171–172 Florence suffered a collapse and "brain fever", while Cox abruptly left for the Priory to collect her belongings and move to other accommodations in London.[10]: 174

On 27 May 1876, the Telegraph reported that the Treasury Solicitor, Augustus Keppel Stephenson, had concluded a preliminary inquiry of thirty witnesses, but that this did not include Florence and Cox, implying that they were both suspects.[10]: 175–176 Anxious to demonstrate their innocence, Florence and Cox each submitted written statements through their solicitor.[10][c] Cox stated in writing that she had perjured herself and suppressed evidence during the first inquest, leading the Lord Chief Justice Sir Alexander Cockburn to grant the Attorney General Sir John Holker's application to open a fresh inquiry.[10]: 176 Florence received a torrent of anonymous hate mail through her letter box in Brighton, and could no longer look out the window toward the Promenade without seeing passersby gazing up at her window.[10]: 190 She paid her servants a month's wages and left Brighton for Buscot Park before returning to the Priory.[10]

Second inquest

[edit]

The second coroner's inquest took place from 11 July through 11 August 1876, in the Bedford Hotel in Balham.[10]: 189, 275 It was attended by Holker himself, with "eminent members of the Bar" holding briefs,[10]: xvii and was covered extensively by members of the press.[4]: 92 Over an unprecedented twenty-three days of testimony,[1] members of the public crowded the streets to try to catch a glimpse of the witnesses giving evidence and find out the latest news each day.[3][4]

Gull, "the most celebrated physician in England",[4]: 81 appeared on the fourth day of the inquest.[10]: 199 He stated that Charles "did not behave like a man who thought he was being murdered" and that "he had showed no surprise" that he was dying of poison.[10][4]: 88 Gull believed that Charles had swallowed antimony intentionally but lost his nerve and had asked for hot water to flush out his system,[4] and remained convinced of Florence's complete innocence.[17]

Interest in the case reached its peak when Florence testified for three days starting 3 August 1876.[3][10]: 248 According author James Ruddick, "For Florence Bravo, the Coroner's inquest was the worst experience of her life."[4]: 92 Rather than focusing on the circumstances leading up to Charles' death, his family's lawyers became fixated with proving that Florence had continued her affair with Gully during their marriage, and subjected Florence, Gully and other witnesses to repeated questions about her past "sexual conduct."[3][4]: 92–93 The lurid details of her "criminal intimacy" with Gully before marrying Charles were covered in depth, in national newspapers such as the Telegraph and The Times, as well as penny newspapers such as The Illustrated Police News,[1][3] and telegraphed by correspondents to newspapers overseas.[4] Florence broke down repeatedly, but on the third day of questioning about details of her sexual history with Gully, she finally objected.[10]: 264 According to The Times, she said "part with tragic force and part tearfully" and with "perfectly just indignation":[10]

"That attachment to Dr Gully has nothing to do with this case—the death of Mr Bravo... I have been subjected to sufficient pain and humiliation already, and I appeal to the Coroner and the jury, as men and Britons, to protect me. I think it is great shame that I should be thus questioned, and I will refuse to answer any further questions with regard to Dr Gully."[3][10]: 264–265

The Saturday Review reported that the audience was sympathetic, and "moved their feet as if applauding."[10]: 265 Other commentators remarked ironically that Charles' own counsel had managed to "let the dead man's own 'criminal intimacy' with a prostitute at Maidenhead remain in decent obscurity."[10] Nevertheless, the coroner allowed lawyer George Lewis to continue this line of questioning, unchecked.[10]

Over the course of the inquest, the likely method of transmission of poison was identified as Charles' water jug, which he drank from each night before going to bed.[4]: 86–87 Although considerable suspicion of Florence remained, there was no direct evidence against her.[4]: 90–91 Florence had not prepared food or given medicine to her husband, and had not signed for any poison in her name.[4]

In the end, the inquest failed to produce any meaningful new evidence.[4]: 94 The Coroner's jury ruled out suicide and "death by misadventure" and found that Charles had been "wilfully murdered by the administration of tartar emetic" by an unknown person or persons.[1][4]

Later life

[edit]Although Florence had avoided being indicted, the public shame and suspicion which persisted destroyed her life.[3][4]: 94 Cox was the first to pack her bags and leave the Priory, followed by her other servants, and Florence received notice that the landlord was taking steps to evict her.[4]: 178 Her eldest brother William urged her to move to Australia with him, but she refused.[4] At the end of September 1876, Florence returned to the Priory and arranged for all its furnishings to be sold by auctioneers Bonham and Son.[4]: 179 She changed her name to Florence Turner and left London permanently on 3 April 1877.[4] She settled in Southsea, Hampshire, where she bought a property called Lumps Villa, which she renamed Coombe Lodge, and hired a housekeeper, two maids and a coachman.[4]: 179–180 Florence rarely went out and eventually drank herself to death, much like her first husband, and died on 17 September 1878 at the age of 33.[3][4]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As part of the settlement, Robert had agreed to pay Florence the annual interest on a £20,000. See Bridge, Yseult (1957), How Charles Bravo Died: The Chronicle of a Cause Célèbre, p. 25.

- ^ During the inquest, the abortion was referred to as a "miscarriage". (Bridges, p. 41)

- ^ Florence Bravo and Jane Cox had offered to give evidence in person, but were informed that any statement they made had to be submitted in writing. (Bridges, p. 175)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Curtis, L. Perry (2008). "Chapter 5. Victorian Murder News". Jack the Ripper and the London Press. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 100–101. doi:10.12987/9780300133691-006. ISBN 978-0-300-13369-1. S2CID 246144449.

- ^ Knelman, Judith (2016). "4. Murder of Husbands, Lovers, or Rivals in Love". Twisting in the Wind: The Murderess and the English Press. University of Toronto Press. p. 115. doi:10.3138/9781442682818-006. ISBN 978-1-4426-8281-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Worsley, Lucy (2022). "1. Florence Bravo" in "Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley". BBC Radio 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz Ruddick, James (2001). Death at the Priory: Love, Sex, and Murder in Victorian England. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-832-8.

- ^ "Robert 'Tertius' Campbell, of Buscot". Clan MacFarlane and associated clans genealogy. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Steven, Margaret (1966). "Campbell junior, Robert (1789–1851)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Connolly, Pauline (1 May 2013). "Buscot Park and the Sydney born bride". Pauline Connolly. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Hartman, Mary S. (1977). Victorian Murderesses: A true history of thirteen respectable French and English women accused of unspeakable crimes. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 134–137. ISBN 0805236082.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hartman, Mary S. (1974). "Crime and the Respectable Woman: Toward a Pattern of Middle-Class Female Criminality in Nineteenth-Century France and England". Feminist Studies. 2 (1): 38–56. doi:10.2307/3177696. JSTOR 3177696.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca Bridges, Yseult (1957). How Charles Bravo Died: The Chronicle of a Cause Célèbre. London: Reprint Society. OL 24975431M.

- ^ a b c d e Worsley, Lucy (2013). A Very British Murder: The Story of a National Obsession. London: BBC Books. pp. 147–148. ISBN 9781849906340.

- ^ "Bell, Hutchinson Royes". King's College London – Victorian Lives. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Sir George Johnson". Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Plarr's Lives of the Fellows – Smith, Henry (1823–1894)". Royal College of Surgeons. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet". Britannica. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Hussey, Kristin (5 April 2019). "'Fools and savages explain: wise men investigate': Sir William Withey Gull". Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b Stewart, Victoria (2017). "Revisiting Victorian Sensations". Crime Writing in Interwar Britain: Fact and Fiction in the Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–44. doi:10.1017/9781108186124.002. ISBN 978-1-108-18612-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Bridges, Yseult (1957). How Charles Bravo Died: The Chronicle of a Cause Célèbre. London: Reprint Society.

- Ruddick, James (2001). Death at the Priory: Love, Sex, and Murder in Victorian England. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

External links

[edit]- Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley: Florence Bravo (BBC Sounds)

- Florence Bravo (née Campbell) (National Portrait Gallery)