Flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World War II as a tactical weapon against fortifications.

Most military flamethrowers use liquid fuel, typically either heated oil or diesel, but commercial flamethrowers are generally blowtorches using gaseous fuels such as propane. Gases are safer in peacetime applications because their flames have less mass flow rate and dissipate faster, and often are easier to extinguish.

Apart from the military applications, flamethrowers have peacetime applications where there is a need for controlled burning, such as in sugarcane harvesting and other land-management tasks. Various forms are designed for an operator to carry, while others are mounted on vehicles.

Military use

[edit]

Modern flamethrowers were first used during the trench warfare conditions of World War I and their use greatly increased in World War II. They can be vehicle-mounted, as on a tank, or man-portable.

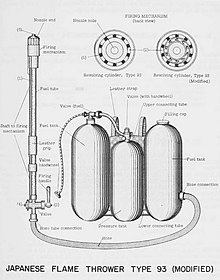

The man-portable flamethrower consists of two elements—the backpack and the gun. The backpack element usually consists of two or three cylinders. In a two-cylinder system, one cylinder holds compressed, inert propellant gas (usually nitrogen), and the other holds flammable liquid, typically some form of petrochemical. A three-cylinder system often has two outer cylinders of flammable liquid and a central cylinder of propellant gas to maintain the balance of the soldier carrying it. The gas propels the liquid fuel out of the cylinder through a flexible pipe and then into the gun element of the flamethrower system. The gun consists of a small reservoir, a spring-loaded valve, and an ignition system; depressing a trigger opens the valve, allowing pressurized flammable liquid to flow and pass over the igniter and out of the gun nozzle. The igniter can be one of several ignition systems: A simple type is an electrically heated wire coil; another used a small pilot flame, fueled with pressurized gas from the system.

Flamethrowers were primarily used against battlefield fortifications, bunkers, and other protected emplacements. A flamethrower projects a stream of flammable liquid, rather than flame, which allows bouncing the stream off walls and ceilings to project the fire into unseen spaces, such as inside bunkers or pillboxes. Typically, popular visual media depict the flamethrower as short-ranged and only effective for a few metres (due to the common use of propane gas as the fuel in flamethrowers in movies, for the safety of the actors). Contemporary flamethrowers can incinerate a target some 50–100 metres (160–330 ft) from the operator; moreover, an unignited stream of flammable liquid can be fired and afterwards ignited, possibly by a lamp or other flame inside the bunker.

Flamethrowers pose many risks to the operator. The first disadvantage is the weapon's weight and length, which impairs the soldier's mobility. The weapon is limited to only a few seconds of burn time, since it uses fuel very quickly, requiring the operator to be precise and conservative. Flamethrowers using a fougasse-style explosive propellant system also have a limited number of shots. The weapon is very visible on the battlefield, which causes operators to become immediately singled out as prominent targets, especially for snipers and designated marksmen. Flamethrower operators were rarely taken prisoner, especially when their target survived an attack by the weapon; captured flamethrower users were in some cases summarily executed.[1]

The flamethrower's effective range is short in comparison with that of other battlefield weapons of similar size. To be effective, flamethrower soldiers must approach their target, risking exposure to enemy fire. Vehicular flamethrowers also have this problem; they may have considerably greater range than a man-portable flamethrower, but their range is still short compared with that of other infantry weapons.

The risk of a flamethrower operator being caught in the explosion of their weapon due to enemy hits on the tanks is exaggerated in films.[2] In some cases, the pressure tanks have exploded and killed the operator when hit by bullets or grenade shrapnel. In the documentary Vietnam in HD, platoon sergeant Charles Brown tells of how one of his men was killed when his flamethrower was hit by grenade shrapnel during the battle for Hill 875.[3]

The pressurizer is filled with a non-flammable gas that is under high pressure. If this tank ruptures, it might knock the operator forward as it was expended in the same way a pressurized aerosol can bursts outward when punctured. The fuel mixture in the containers is difficult to light, which is why magnesium-filled igniters are required when the weapon is fired. When pierced by a bullet, a metal can filled with diesel or napalm will merely leak unless the round is an incendiary type that may ignite the mixture inside.[4]

The best way to minimize the disadvantages of flame weapons was to mount them on armoured vehicles. The Commonwealth and the United States were the most prolific users of vehicle-mounted flame weapons; the British and Canadians fielded "Wasps" (Universal Carriers fitted with flamethrowers) at infantry battalion level, beginning in mid-1944, and eventually incorporating them into infantry battalions. Early tank-mounted flamethrower vehicles included the "Badger" (a converted Ram tank) and the "Oke", used first at Dieppe.[2]

Operation

[edit]A propane-operated flamethrower is a straightforward device. The gas is expelled through the gun assembly by its own pressure and is ignited at the exit of the barrel through piezo ignition.

Liquid-operated flamethrowers use a smaller tank with a pressurized gas to expel the flammable liquid fuel. The propellant gas is fed to two tubes. The first opens in the fuel tanks providing the pressure necessary for expelling the liquid.[5] The other tube leads to an ignition chamber behind the exit of the gun assembly, where it is mixed with air and ignited through piezo ignition. This pre-ignition line is the source of the flame seen in front of the gun assembly in movies and documentaries. As the fuel passes through the flame, it is ignited and propelled towards the target.

History

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]

The concept of projecting fire as a weapon has existed since ancient times. During the Peloponnesian War, Boeotians used some kind of a flamethrower trying to destroy the fortification walls of the Athenians during the Battle of Delium.[6]

Roman Empire

[edit]In 107 AD the Romans used a flamethrower against the Dacians; the device was similar to the one used at Delium.[7]

Later, during the Byzantine era, sailors used rudimentary hand-pumped flamethrowers on board their naval ships. Greek fire, extensively used by the Byzantine Empire, is said to have been invented by Kallinikos of Heliopolis, probably about 673 AD. Byzantine texts described weapons, used by Byzantine land forces, which were shooting Greek fire and called cheirosiphona (χειροσίφωνα, meaning hand-held siphons, singular χειροσίφωνο).[8][9] The flamethrower found its origins in a device consisting of a hand-held pump that shot bursts of Greek fire via a siphon-hose and a piston which ignited it with a match, similar to modern versions, as it was ejected.[10] An illustration in Poliorcetica of Hero of Byzantium display a soldier with a portable flamethrower.[11][12] Byzantines also used ceramic hand grenades filled with Greek fire.[13][14] Greek fire, used primarily at sea, gave the Byzantines a substantial military advantage against enemies such as members of the Arab Empire (who later adopted the use of Greek fire). An 11th-century illustration of its use survives in the John Skylitzes manuscript.

China

[edit]

The Pen Huo Qi ("fire spraying device") was a Chinese piston flamethrower that used a substance similar to petrol or naphtha, invented around 919 AD during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The earliest reference to Greek fire in China was made in 917, written by Wu Renchen in his Spring and Autumn Annals of the Ten Kingdoms.[15] In 919, the siphon projector-pump was used to spread the 'fierce fire oil' that could not be doused with water, as recorded by Lin Yu (林禹) in his Wu-Yue Beishi (吳越備史), hence the first credible Chinese reference to the flamethrower employing the chemical solution of Greek fire.[16] Lin Yu mentioned also that the 'fierce fire oil' derived ultimately from China's contact in the 'southern seas', with Arabia (大食國 Dashiguo).[17] In the Battle of Langshan Jiang (Wolf Mountain River) in 919, the naval fleet of the Wenmu King of Wuyue defeated the fleet of the Kingdom of Wu because he had used 'fire oil' to burn his fleet; this signified the first Chinese use of gunpowder in warfare, since a slow-burning match fuse was required to ignite the flames.[18] The Chinese applied the use of double-piston bellows to pump petrol out of a single cylinder (with an upstroke and a downstroke), lit at the end by a slow-burning gunpowder match to fire a continuous stream of flame (as referred to in the Wujing Zongyao manuscript of 1044).[17] In the suppression of the Southern Tang state by 976 AD, early Song naval forces confronted them on the Yangtze River in 975. Southern Tang forces attempted to use flamethrowers against the Song navy, but were accidentally consumed by their own fire when violent winds swept in their direction.[19] Documented also in later Chinese publications, illustrations and descriptions of mobile flamethrowers on four-wheel push carts appear in the Wujing Zongyao, written in 1044 (its illustration redrawn in 1601 as well).[20] Advances in military technology aided the Song dynasty in its defense against hostile neighbours to the north, including the Mongols.

Islamic World

[edit]Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Khwārazmī in Mafātīḥ al-ʿUlūm (“Keys to the Sciences”) ca. 976 AD mentions the bāb al-midfa and the bāb al-mustaq which he said were parts of naphtha-throwers and projectors (al-naffātāt wa al-zarāqāt). Book of Ingenious Mechanical Device (Kitāb fī ma 'rifat al-ḥiyal al-handasiyya) of 1206 by Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari mentioned about ejectors of naphtha (zarāqāt al-naft).[21]: 582

18th century

[edit]In 1702, the Prussian Army tested P. Lange's "serpent-fire-spray'' (Schlangen-Brand-Spritze) who produced a jet of fire 4 metres (12 ft) wide and 40 m (120 ft) long; two years later it was rejected as useless.[22]

Peter the Great's chief engineer Vasily Dmitrievich Korchmin designed various incendiary weapons.such as incendiary rockets and furnaces for heating cannonball; two Russian ships the “Svyatoy Yakov” and “Landsou” were armed with flamethrower tubes designed by him. He also developed instructions for their use together with the Tsar.[23]

In the 1750s a French engineer named Dupre, developed a new flammable mixture; it was tested in LeHavre and set fire to a sloop. During the British shelling of LeHavre in 1759, the French War Minister tried to obtain authorization to use this fuel.[22]

19th century

[edit]Although flamethrowers were never used in the American Civil War, "Greek Fire" shells were produced and used by Union troops during the Second Battle of Charleston Harbor.[24][25]

During the 1871 siege of Paris, French chemist Marcellin Berthelot suggested pumping flaming petroleum at Prussian troops.[22]

In 1898 Russian captain Sigern-Korn experimented with burning jets of kerosene for defensive use; in theory in they would be fired from parapets of fortifications. The idea was abandoned due to technical issues[26]

Early 20th century

[edit]

During the siege of Port Arthur, Japanese combat engineers used hand pumps to spray kerosene into Russian trenches. Once the Russians were covered with the flammable liquid, the Japanese would throw bundles of burning rags at them.[27]

Before WW1 German pioneers used the Brandröhre M.95 a weapon consisting of a sheet metal tube (125 mm (4.9 in) wide and 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long) filled with an incendiary mixture, and a friction igniter activated by a lanyard. The Brandröhre was designed to be used against enemy casemates; a long pole was used to reach the target and the lanyard was pulled to ignite the fuel; producing a 2-metre (7 ft) long stream of fire. Those weapons were deployed in six-man teams and were limited by their short range. In theory the Brandröhre was replaced by the flamethrower in 1909 but it was still in use in WW1; it was used during the assaults on Fort du Camp-des-Romains in 1914 and Fort Vaux in 1916.[28][29]

Bernhard Reddeman, a German military officer and former fireman, converted steam powered fire engines into flamethrowers; his design was demonstrated in 1907.[28][30]

The English word flamethrower is a loan-translation of the German word Flammenwerfer, since the modern flamethrower was invented in Germany. The first flamethrower, in the modern sense, is usually credited to Richard Fiedler. He submitted evaluation models of his Flammenwerfer to the German Army in 1901. The most significant model submitted was a portable device, consisting of a vertical single cylinder 1.2 metres (4 ft) long, horizontally divided in two, with pressurized gas in the lower section and flammable oil in the upper section. On depressing a lever the propellant gas forced the flammable oil into and through a rubber tube and over a simple igniting wick device in a steel nozzle. The weapon projected a jet of fire and enormous clouds of smoke some 18 metres (20 yd). It was a single-shot weapon—for burst firing, a new igniter section was attached each time. In 1905 Fiedler's flamethrower was demonstrated to the Prussian Committee of Engineers. In 1908 Fiedler started working with Reddeman and made some adjustments to the design; an experimental pioneer company was created to further test the weapon.[28][30]

It was not until 1911 that the German Army accepted their first real flamethrowing device, creating a specialist regiment of twelve companies equipped with Flammenwerfer Apparent.[31] Despite this, use of fire in a World War I battle predated flamethrower use, with a petrol spray being ignited by an incendiary bomb in the Argonne-Meuse sector in October 1914.[32]

The flamethrower was first used in World War I on 26 February 1915 when it was briefly used against the French outside Verdun.[33] On 30 July 1915 it was first used in a concerted action, against British trenches at Hooge, where the lines were 4.5 m (4.9 yd) apart—even there, the casualties were caused mainly by soldiers being flushed into the open and then shot rather than from the fire itself.[32] After two days of fighting the British had suffered casualties of 31 officers and 751 other ranks.[34]

The success of the attack prompted the German Army to adopt the device on all fronts. Flamethrowers were used in squads of six during battles, at the start of an attack destroying the enemy and to the preceding the infantry advance.[34]

The flamethrower was useful at short distances[34] but had other limitations: it was cumbersome and difficult to operate and could only be safely fired from a trench, which limited its use to areas where the opposing trenches were less than the maximum range of the weapon, namely 18 m (20 yd) apart—which was not a common situation; the fuel would also only last for about a minute of continuous firing.[32]

The German deployed flamethrowers during the war in more than 650 attacks.[34]

The Ottoman Empire received 30 flamethrowers from Germany during the war.[35][36]

German flamethrowers were also used by Bulgarian forces.[35]

Austria-Hungary adopted German designs; but also developed its own flamethrowers in 1915. These included the 50 litres (13 US gal) M.15 Flammenwerfer, which required a crew of three men and was too unwieldy for offensive use; a defensive 200 litres (53 US gal) model and a more portable 22 litres (5.8 US gal) model were also produced. Austro-Hungarian flamethrowers were unreliable and long hoses were used to prevent the shooter from igniting the fuel tank[35][37]

The British experimented with flamethrowers in the Battle of the Somme, during which they used experimental weapons called "Livens Large Gallery Flame Projectors", named for their inventor, William Howard Livens, a Royal Engineers officer.[38] This weapon was enormous and completely non-portable. The weapon had an effective range of 80 metres (90 yd), which proved effective at clearing trenches, but with no other benefit the project was abandoned.[34]

Two Morriss static flamethrowers were mounted in HMS Vindictive and several Hay portable flamethrowers were deployed by the Royal Navy during the Zeebrugge Raid on 23 April 1918. A British newspaper report of the action referred to the British flamethrowers only as flammenwerfer, using the German word.[39]

The French Army deployed the Schilt family of flamethrowers, which were also used by the Italian Army.[40]

In 1931 the São Paulo Public Force created an assault car section. The first vehicle to be incorporated was a tank built from a Caterpillar Twenty Two tractor, featuring a turret mounted flamethrower and four Hotchkiss machineguns on the hull. It was used in combat during the Constitutionalist Revolution, routing federal troop from a bridge in an engagement in Cruzeiro.[41]

In the interwar period, at least four flamethrowers were used in the Chaco War by the Bolivian Army, during the unsuccessful assault on the Paraguayan stronghold of Nanawa in 1933.[42] During the battle of Kilometer 7 to Saavedra, Major Walther Kohn rode in a flamethrower equipped tankette; due to heat he exited the tank to fight on foot and was killed in combat.[43]

World War II

[edit]The flamethrower was used extensively during World War II. In 1939, the Wehrmacht first deployed man-portable flamethrowers against the Polish Post Office in Danzig. Subsequently, in 1942, the U.S. Army introduced its own man-portable flamethrower. The vulnerability of infantry carrying backpack flamethrowers and the weapon's short range led to experiments with tank-mounted flamethrowers (flame tanks), which were used by many countries.

Axis use

[edit]Germany

[edit]-

A German soldier operating a flamethrower in 1944

-

A German soldier using a flamethrower in Russia

-

Belgian soldier wounded by a flamethrower (World War I)

The Germans made considerable use of the weapon (Flammenwerfer 35) during their invasion of the Netherlands and France, against fixed fortifications. World War II German army flamethrowers tended to have one large fuel tank with the pressurizer tank fastened to its back or side. Some German army flamethrowers occupied only the lower part of its wearer's back, leaving the upper part of his back free for an ordinary rucksack.

Flamethrowers soon fell into disfavour. Flamethrowers were extensively used by German units in urban fights in Poland, both in 1943 in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and in 1944 in the Warsaw Uprising (see the Stroop Report and the article on the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising). With the contraction of the Third Reich during the latter half of World War II, a smaller, more compact flamethrower known as the Einstossflammenwerfer 46 was produced.

Germany also used flamethrower vehicles, most of them based on the chassis of the Sd.Kfz. 251 half track and the Panzer II and Panzer III tanks, generally known as Flammpanzers.

The Germans also produced the Abwehrflammenwerfer 42, a flame-mine or flame fougasse, based on a Soviet version of the weapon.[44] This was essentially a disposable, single use flamethrower that was buried alongside conventional land mines at key defensive points and triggered by either a trip-wire or a command wire. The weapon contained around 30 litres (8 US gal) of fuel, that was discharged within a second, to a second and a half, producing a flame with a 14-metre (15 yd) range.[44] One defensive installation found in Italy included seven of the weapons, carefully concealed and wired to a central control point.[44]

Finland

[edit]

During the Winter War Finland adopted the Italian Lanciafiamme Modello 35 as the Liekinheitin M/40; 176 flamethrowers were ordered but only 28 arrived before the end of the war.[45]

Those flamethrowers were not used in the Winter War; but were issued to engineers during the Continuation War along with captured ROKS-2 flamethrowers[45]

OT-130 and OT-133 flame tanks were captured from the Soviet Union and issued at the start of the Continuation War; they were considered impratical and later retrofitted with cannons.[46]

In 1944 they developed and adopted the Liekinheitin M/44.[47]

Italy

[edit]Italy employed man-portable flamethrowers and L3 Lf flame tanks during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935 to 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, and during World War II. The L3 Lf flame tank was a CV-33 or CV-35 tankette with a flamethrower operating from the machine gun mount. In the Northern Africa Theatre, the L3 Lf flame tank found little to no success.[48] An L6 Lf flametank was also developed using the L6/40 light tank platform.

Japan

[edit]

Japan used man-portable flamethrowers to clear fortified positions, in the Battle of Wake Island,[49] Corregidor,[50] Battle of the Tenaru on Guadalcanal[51] and Battle of Milne Bay.[52]

Romania

[edit]Flamethrowers were also used by the Royal Romanian Army. They were also planned to become self-propelled; the Mareșal tank destroyer was planned to have a command vehicle version armed with machine guns and a flamethrower.[53]

Allies

[edit]Britain and the Commonwealth

[edit]-

A British World War II–type "lifebuoy" flamethrower in 1944

-

A Churchill tank fitted with a Crocodile flamethrower in action.

-

An Australian soldier fires a flamethrower at a Japanese bunker

The British World War II army flamethrowers, "Ack Packs", had a doughnut-shaped fuel tank with a small spherical pressurizer gas tank in the middle. As a result, some troops nicknamed them "lifebuoys". It was officially known as Flamethrower, Portable, No 2.

Extensive plans were made in 1940–1941 by the Petroleum Warfare Department to use flame fougasse static flame projectors in the event of an invasion, with around 50,000 barrel-based incendiary mines being deployed in 7,000 batteries throughout Southern England.[54]

The British hardly used their man-portable systems, relying on Churchill Crocodile tanks in the European theatre. These tanks proved very effective against German defensive positions, and caused official Axis protests against their use.[citation needed] This flamethrower could produce a jet of flame exceeding 140 metres (150 yd). There are documented instances of German units summarily executing any captured British flame-tank crews.[55]

In the Pacific theatre, Australian forces used converted Matilda tanks, known as Matilda Frogs.

United States

[edit]-

A soldier from the 33rd Infantry Division uses an M2 flamethrower

-

Marines engaging Japanese positions on Guam with a flamethrower.

-

2nd Marine tank Battalion "Satan" incinerates Japanese pillbox on Saipan

-

An American flamethrower operator runs under fire

-

Front and rear views of a man with an M2A1-7 United States Army flamethrower

In the Pacific theatre, the U.S. Army used M-1 and M-2 flamethrowers to clear stubborn Japanese resistance from prepared defenses, caves, and trenches. Starting in New Guinea, through the closing stages on Guadalcanal and during the approach to and reconquest of the Philippines and then through the Okinawa campaign, the Army deployed hand-held, man-portable units.

Often flamethrower teams were made up of combat engineer units, later with troops of the chemical warfare service. The Army fielded more flamethrower units than the Marine Corps, and the Army's Chemical Warfare Service pioneered tank mounted flamethrowers on Sherman tanks (CWS-POA H-4). All the flamethrower tanks on Okinawa belonged to the 713th Provisional Tank Battalion, which was tasked with supporting all U.S. Army and Marine infantry. All Pacific mechanized flamethrower units were trained by Seabee specialists with Col. Unmacht's CWS Flamethrower Group in Hawaii.

The U.S. Army used flamethrowers in Europe in much smaller numbers, though they were available for special employments. Flamethrowers were deployed during the Normandy landings in order to clear Axis fortifications.[56][57] Also, most boat teams on Omaha Beach included a two-man flamethrower team.[58]

The Marine Corps used the backpack-type M2A1-7 and M2-2 flamethrowers, finding them useful in clearing Japanese trench and bunker complexes. The first known USMC use of the man portable flamethrower was against the formidable defenses at Tarawa in November 1943. The Marines pioneered the use of Ronson-equipped M-3 Stuart tanks in the Marianas. These were known as SATAN flame tanks. Though effective, they lacked the armour to safely engage fortifications and were phased out in favour of the better-armoured M4 Sherman tanks. USMC Flamethrower Shermans were produced at Schofield Barracks by Seabees attached to the Chemical Warfare Service under Col. Unmacht. CWS designated M4s with "CWS-POA-H" for "Chemical Warfare Service Pacific Ocean Area, Hawaii" plus a flamethrower number. The Marines had previously deployed large Navy flamethrowers mounted on LVT-4 AMTRACs at Peleliu. Late in the war, both services operated LVT-4 and −5 amphibious flametanks in limited numbers. Both the Army and the Marines still used their infantry-portable systems, despite the arrival of adapted Sherman tanks with the Ronson system (cf. flame tanks).

In cases where the Japanese were entrenched in deep caves, the flames often consumed the available oxygen, suffocating the occupants. Many Japanese troops interviewed post war said they were terrified more by flamethrowers than any other American weapon. Flamethrower operators were often the first U.S. troops targeted.

Soviet Union

[edit]

The FOG-1 and −2 flamethrowers were stationary devices used in defense. They could also be categorized as a projecting incendiary mine. The FOG had only one cylinder of fuel, which was compressed using an explosive charge and projected through a nozzle. The November 1944 issue of the US War Department Intelligence Bulletin refers to these "Fougasse flame throwers" being used in the Soviet defense of Stalingrad. The FOG-1 was directly copied by the Germans as the Abwehrflammenwerfer 42.

Unlike the flamethrowers of the other powers during World War II, the Soviets were the only ones to consciously attempt to camouflage their infantry flamethrowers. With the ROKS-2 flamethrower this was done by disguising the flame projector as a standard-issue rifle, such as the Mosin–Nagant, and the fuel tanks as a standard infantryman's rucksack. This was to try to stop the flamethrower operator from being specifically targeted by enemy fire.[59] This "rifle" had a working action which was used to cycle blank igniter cartridges.

1945–1980

[edit]US military

[edit]

The United States Marines used flamethrowers in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. The M132 armored flamethrower, an M113 armored personnel carrier with a mounted flamethrower, was successfully used in the conflict.[60]

Flamethrowers have not been in the U.S. arsenal since 1978, when the Department of Defense unilaterally stopped using them — the last American infantry flamethrower was the Vietnam-era M9-7. They have been deemed of questionable effectiveness in modern combat, though some have made the case for their tactical employment.[61]

U.S. army flamethrowers developed up to the M9 model. In the M9 the propellant tank is a sphere below the left fuel tank and does not project backwards.

Israel

[edit]Crude homemade flamethrowers were built by Irgun in the late 1940s.[62]

China

[edit]The PLA adopted the Type 74 flamethrower, a copy of the Soviet LPO-50. It was later used in the Sino-Vietnamese War.[63][64]

Vietnam

[edit]LPO-50[65] and Type 74 flamethrowers were used by NVA forces during the Vietnam War.[64]

Iraq

[edit]The Iraqi army used LPO-50 flamethrowers during the Iran-Iraq War.[66]

Post-1980s

[edit]Non-flamethrower incendiary weapons remain in modern military arsenals. Thermobaric weapons may have been fielded in Afghanistan by the United States (2008)[67][68] and have been used by Russia in Ukraine (2022).[69] The U.S. and U.S.S.R. both developed a rocket launcher specifically for the deployment of incendiary munitions, respectively the M202 FLASH and the RPO "Rys" ancestor of the RPO-A Shmel.

Vietnam

[edit]The Type 74 is still being used by the Vietnamese Army.[64]

French assault on Ouvéa cave (1988)

[edit]On 22 April 1988, Kanak rebels took 36 French hostages in Ouvéa island, New Caledonia, most of them gendarms and military personnel. On 5 May, after weeks of fruitless negotiations, a team of gendarms and paratroopers from the French Army launched a rescue operation. During the assault, a rebel machine gun position was neutralized using a flamethrower. All hostages were eventually set free.[70]

Provisional IRA

[edit]In 1981 the FBI foiled an attempt by New York-based gun runner George Harrison to smuggle an M2 flamethrower to Ireland for the IRA.[71][72] In the last stages of the Troubles, during the mid-1980s, the IRA smuggled in Soviet LPO-50 military flamethrowers (supplied to them by the Libyan government) into Northern Ireland.[73] An IRA team riding on an improvised armoured truck used one of these flamethrowers, among other weapons, to storm a British Army permanent checkpoint in Derryard, near Rosslea, on 13 December 1989.[74] Some months later, on 4 March 1990, the IRA attacked an RUC station in Stewartstown, County Tyrone, using an improvised flamethrower consisting of a manure-spreader towed by a tractor to spray 2,700 L (590 imp gal; 710 US gal) of a petrol/diesel mix to engulf the base in flames, and then opened fire with rifles and an anti-tank rocket launcher.[75][76][77][78] Another IRA unit carried two attacks in less than a year with another improvised flamethrower towed by a tractor on a British Army watchtower, the Borucki sangar, in Crossmaglen, County Armagh, also in the early 1990s. The first incident occurred on 12 December 1992,[79] when the bunker was manned by Scots Guards, and the second on 12 November 1993. The device used as launcher was also a manure spreader, which doused the facility with fuel, ignited few seconds later by a small explosion. In the 1993 action, a nine-metre-high fireball engulfed the tower for seven minutes. The four Grenadier Guards inside the outpost were rescued by a Saxon armoured vehicle.[80] Incendiary improvised devices were also proven by the republican paramilitaries, such as an IRA grenade attack on a British Army patrol on 4 April 1993 in Carrickmore, County Tyrone; the device consisted of 0.9 kg (2 lb) of semtex and 22.5 litres (4.9 imp gal; 5.9 US gal) of petrol; the bomb exploded, but the fuel failed to ignite. A soldier was thrown several metres across the road by the blast.[81]

Brazil

[edit]As of 2003 the locally made Hydroar T1M1 flamethrower was still being used by the 1º Batalhão de Forças Especiais.[82]

China

[edit]The Chinese Army still issues the Type 74 flamethrower.[64]

During an operation to hunt down the militant group responsible for the 2015 Aksu colliery attack, after using tear gas and flash grenades to no avail, Chinese paramilitary forces resorted to flamethrowers to root out suspected militants who were hiding in a cave.[83][84]

Iraq conflict

[edit]Captain Shannon Johnson requested colonel John A. Toolan to supply his company with flamethrowers during the Battle of Fallujah; however no flamethrowers were issued.[85]

The People's Mujahedin of Iran claimed flamethrowers were used in the 2013 Camp Ashraf massacre[86]

Myanmar

[edit]Flamethrowers have been used by the Tatmadaw during attacks on Rohingya villages during the Rohingya genocide.[87][88]

Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]On 8 February 2017, separatist leader Mikhail 'Givi' Tolstykh was killed when an RPO-A Shmel rocket-assisted flamethrower was fired at his office in Donetsk.[89]

On 21 November 2022, nine months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian sources claim that artillery and "heavy flamethrowers" were employed against a Ukrainian concentration of troops near Kupyansk, Kharkiv Oblast.[69] Russian sources use the term "heavy flamethrowers" to describe TOS-1 multiple thermobaric rocket launchers.[90]

International law

[edit]Despite some assertions, flamethrowers are not generally banned. However the United Nations Protocol on Incendiary Weapons forbids the use of incendiary weapons (including flamethrowers) against civilians. It also forbids their use against forests unless they are used to conceal combatants or other military objectives.

Owning a personal flamethrower

[edit]In the United States, private ownership of a flamethrower is not restricted by federal law, because a flamethrower is a tool, not a firearm. Flamethrowers are legal in 48 states and restricted in California and Maryland.[91][92]

In California, unlicensed possession of a flame-throwing device—statutorily defined as "any non-stationary and transportable device designed or intended to emit or propel a burning stream of combustible or flammable liquid a distance of at least 10 feet (3.0 m)" H&W 12750 (a)—is a misdemeanor punishable with a county jail term not exceeding one year or with a fine not exceeding $10,000 (CA H&W 12761). Licenses to use flamethrowers are issued by the state fire marshal, and they may use any criteria for issuing or not issuing that license which is deemed fit, but must publish those criteria in the California Code of Regulations, Title 11, Section 970 et seq.[93][94][95][96]

In the United Kingdom, flamethrowers are "prohibited weapons" under section 5(1)(b) of the Firearms Act 1968[97] and article 45(1)(f) of the Firearms (Northern Ireland) Order 2004 and possession of a flamethrower would carry a sentence of up to ten years' imprisonment.[98] On 16 June 1994, a man attacked school pupils at Sullivan Upper School, just outside Belfast, with a home-made flamethrower.[99]

A South African inventor brought the Blaster car-mounted flamethrower to market in 1998 as a security device to defend against carjackers.[100] It has since been discontinued, with the inventor moving on to pocket-sized self-defence flamethrowers.[101]

Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, Inc. and owner of SpaceX, developed a "not a flamethrower" for public sale through his business, The Boring Company, selling 20,000 units. This device uses liquid propane gas rather than a stream of gasoline, making it more akin to a torch, like those commonly available at home and garden centers.[102]

Other uses

[edit]Flamethrowers are occasionally used for igniting controlled burns for land management and agriculture. For example, in the production of sugar cane, where canebrakes are burned to get rid of the dry dead leaves which clog harvesters, and incidentally kill any lurking venomous snakes. More commonly, a driptorch or a flare (fusee) is used.[103]

U.S. troops allegedly used flamethrowers on the streets of Washington, D.C. (mentioned in a December 1998 article in the San Francisco Flier), as one of several clearance methods used for the surprisingly large amount of snow that fell before the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy.[104] A history article on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers notes, "In the end, the task force employed hundreds of dump trucks, front-end loaders, sanders, plows, rotaries, and allegedly flamethrowers to clear the way".[104]

Flamethrowers were employed by U.S. combat engineers during the Iraq War; they were used to clear brush and eliminate hiding spots for insurgents[105]

A squad armed with backpack flamethrowers had an important part in the 2012 Summer Paralympics closing ceremony. They had one big tank each. They could make a flame about 4 metres (12 ft) long.

In April 2014 it was reported by South Korea's Chosun Ilbo newspaper without confirmation that a North Korean government official, O Sang-Hon, Deputy Minister at the Ministry of Public Security, was executed by flamethrower.[106]

In August 2016 it was reported that the Islamic State used flamethrowers to execute six of its commanders in Tal Afar as punishment for their attempt to escape to Syria[107]

It has been known for police to fill a "flamethrower", not with flammable liquid, but rather with tear gas dissolved in water as a riot-control device; see Converted Flamethrower 40.

See also

[edit]- Dragon's breath

- Early thermal weapons

- Flame gun

- Huo Long Jing

- Le Prieur rocket

- List of flamethrowers

- M202A1 FLASH

- Meng Huo You

- Molotov cocktail

- Petroleum Warfare Department

- Technology of Song dynasty

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Why Has the US Military Discontinued Use of Flamethrowers?". Archived from the original on July 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "Flamethrower". canadiansoldiers.com. Archived from the original on 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Vietnam in HD", Wikipedia, 2024-07-11, retrieved 2024-10-21

- ^ Gordon, David. Weapons of the WWII Tommy

- ^ Harris, Tom (25 October 2001). "HowStuffWorks "How Flamethrowers Work"". Science.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ "History of the Peloponnesian War" – via Wikisource.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ Dr. Ilkka Syvänne (2017). Caracalla: A Military Biography. Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1473895249.

In later Byzantine texts, the syringe was replaced by cheirosiphona (hand-held siphons) that were also used to shoot Greek Fire.

- ^ John W Nesbitt (2003). Byzantine Authors: Literary Activities and Preoccupations. Brill. p. 189. ISBN 978-9004129757.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, 77.

- ^ John Pryor; Elizabeth M Jeffreys (2006). The Age of the DROMON: The Byzantine Navy ca 500–1204. Brill. p. 619. ISBN 978-9004151970.

- ^ Vatican Library - Manuscript - Vat.gr.1605

- ^ Byzantine Hand Grenade with Circular Designs

- ^ Byzantine Clay Hand Grenade

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, 80.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, 81.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, 82.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 81–83.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, 89.

- ^ File:Battle of kedah.jpg

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c McKinney, Leonard L. Chemical Corps Historical Studies - Portable Flame Thrower Operations in World War II.

- ^ "Интересные факты из истории флота". www.navy.su. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- ^ Hasegawa, Guy R. (5 May 2008). "Proposals for Chemical Weapons during the American Civil War". Military Medicine. 173 (5). Oxford University Press: 499–506. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.5.499. PMID 18543573. S2CID 25643354.

- ^ Symonds, Craig L. (2012). The Civil War at Sea. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-19-993168-2.

- ^ "Огнеметное оружие Великой войны. Ч. 1. В поисках "огнедышащего дракона"". btgv.ru. Retrieved 2023-12-16.

- ^ ""These Hideous Weapons"". HistoryNet. 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ a b c McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ Wictor, Thomas (2012-05-25), German Fire Tube, retrieved 2023-12-13

- ^ a b "The Soldier at the Western Front – The Use of Flamethrower - Source 4: Bernhard Reddemann: History of the German Flamethrower troop". www.hi.uni-stuttgart.de. Retrieved 2023-12-16.

- ^ The New Shell Book of Firsts – Patrick Robertson (Headline)

- ^ a b c First World War, Willmott, H. P., Dorling Kindersley, 2003, p. 106

- ^ Clodfelter 2017, p. 394.

- ^ a b c d e "First World War.com – Weapons of War: Flamethrowers". www.firstworldwar.com.

- ^ a b c McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ "Weaponry". Turkey in the First World War. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ Copping, Jasper (9 May 2010). "Secret terror weapon of the Somme battle 'discovered'". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 26 April 1918, reprinted in the Daily Telegraph, 26 April 2018

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ "Blindados em 1932". netleland.net. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's, p. 97. ISBN 1-57488-452-2.

- ^ Sigal Fogliani, Ricardo (1997). Blindados Argentinos, de Uruguay y Paraguay (in Spanish). Buenos Aires.: Ayer y Hoy. pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c "Fougasse Flame Throwers from Intelligence Bulletin, November 1944". lonesentry.com. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ a b "FINNISH ARMY 1918 - 1945: PORTABLE FLAME-THROWERS". www.jaegerplatoon.net. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ "FINNISH ARMY 1918 - 1945: FLAME TANKS". www.jaegerplatoon.net. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "Flames in Ice and Snow: Flamethrowers of the Finnish Army - Small Arms Review". June 6, 2023.

- ^ World War II, Willmott, H.P., Dorling Kindersley, 2004, Page 165, ISBN 1-4053-0477-4

- ^ Devereux, Col. James P. F. "There are Japanese in the Bushes..." in The United States Marine Corps in World War II compiled and edited by S. E. Smith, Random House, 1969, p.50.

- ^ World War II, Willmott, H.P., Dorling Kindersley, 2004, Page 121, ISBN 1-4053-0477-4

- ^ p.108 Hinton, David R. Letters from the Dead: Guadalcanal 2005 Hinton Publishing

- ^ Boettcher, Brian Eleven Bloody Days: The Battle for Milne Bay self published 2009

- ^ Scafeș, Cornel (2004). "Buletinul Muzeului Național Militar, Nr. 2/2004" [Bulletin of the National Military Museum, No. 2/2004]. National Military Museum (in Romanian). Bucharest: Total Publishing., p. 229

- ^ "Yeovil's Virtual Museum, the A-to-Z of Yeovil's History - by Bob Osborn". www.yeovilhistory.info. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ Jarymowycz, Roman Johann (2001). Tank Tactics: From Normandy to Lorraine. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 199. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- ^ Holderfield, Randy (2001). D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy, June 6, 1944. Da Capo Press. p. 76. ISBN 1-882810-46-5.

- ^ Drez, Ronald (1998). Voices of D-Day: The Story of the Allied Invasion, Told by Those Who Were There. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 35, 201–211. ISBN 0-8071-2081-2.

- ^ Balkoski, Joseph (2004). Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944. Stackpole Books. p. 368. ISBN 0-8117-0079-8.

- ^ Chris Bishop (2002). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. Sterling Publishing Company. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-58663-762-0.

- ^ Renquist, Capt. John (Summer 2008). "U.S Army Flamethrower Vehicles (Part Three of a Three-Part Series)" (Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine). CML Army Chemical Review. Wood.army.mil.

- ^ Keller, Jared (2018-01-26). "A Vietnam War veteran explains the tactical case for the flamethrower". Business Insider. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ "Type 74 Flamethrower still in Active Use, Chinese PLA Police Scorch some O2 -". The Firearm Blog. 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ a b c d "North Vietnam's Type 74 Flamethrower". HistoryNet. 2022-04-26. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ Olofsson, Magnus (2020-05-16). "Iran-Irakkriget i bilder". Militarhistoria.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (3 December 2015). "The American Military's Deadly Thermobaric Arsenal". The National Interest. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Hambling, David (May 15, 2009). "U.S. Denies Incendiary Weapon Use in Afghanistan". Wired.com. Accessed 27 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Russian troops wipe out four command posts in Ukraine operation — top brass". TASS. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ Waddell, Eric (2008-08-31). Jean-Marie Tjibaou, Kanak Witness to the World: An Intellectual Biography. University of Hawaii Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8248-3314-5.

- ^ Alexander, Shana. "The Patriot Game". _New York_, 22 November 1982. pg 58+. Retrievable from

- ^ World in Action (Television documentary). ITN. 22 February 1982.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin, Syracuse University Press, p. 279. ISBN 0-8156-0597-8

- ^ Moloney, Ed (2003). A secret story of the IRA. W.W. Norton & co., p. 333. ISBN 0-393-32502-4

- ^ Fortnight, No. 283, pp. 20–21. Fortnight Publications, 1990.

- ^ Irish Independent, 6 March 1990.

- ^ Dundee Courier, 6 March 1990.

- ^ Derby Daily Telegraph, 5 March 1990.

- ^ "Loyalists fire rocket at prison canteen". The Independent. 1992-12-14. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Harnden, Toby (2001). Bandit Country: The IRA & South Armagh. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 123–24. ISBN 0-340-71736-X.

- ^ "War News". indianamemory.contentdm.oclc.org. The Irish People. 17 April 1993. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ Miller, David (2002). The illustrated directory of special forces. St Paul, MN: MBI. ISBN 0-7603-1419-5. OCLC 51555045.

- ^ "Flamethrower used to flush out militants in China's Xinjiang region, says state media". South China Morning Post. 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ "China forces used flamethrower to hunt Xinjiang 'terrorists': army newspaper". Reuters. 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ West, Bing (2006). No True Glory: A Frontline Account of the Battle for Fallujah. p. 176.

- ^ "Iraq, attacco agli esuli iraniani". La Stampa (in Italian). 2013-09-01. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "Rohingya experienced 'extreme' violence in Myanmar". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ Beech, Hannah; Nang, Saw; Simons, Marlise (2020-09-08). "'Kill All You See': In a First, Myanmar Soldiers Tell of Rohingya Slaughter". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ "Site of "DPR" militant chief Givi assassination". www.unian.info. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ "Heavy flamethrower system TOS-1A | Rosoboronexport". roe.ru. Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- ^ "See the terrifying personal flamethrower that's apparently legal in 48 states". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ^ http://xm42.com/volusion/mapRestricted.png [bare URL image file]

- ^ CA Regs (CA H&W 12756)

- ^ "Definitions and scope".

- ^ "Administration". leginfo.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-01-17. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ "Enforcement and penalties". leginfo.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ "Firearms Act 1968". www.opsi.gov.uk.

- ^ "Firearms Act 1968". www.opsi.gov.uk.

- ^ "Pupils hurt in 'flame-thrower' attack". The Independent. October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Flamethrower now an option on S. African cars". CNN. December 11, 1998. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ Fourie, Charl (2001-02-13). "Personal Flame Thrower". AM (ABC Radio) (Interview). Interviewed by Sara Sally.

- ^ "Elon Musk sells all 20,000 Boring Company 'flamethrowers'". The Guardian. London. February 1, 2018. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ "FAQ". throwflame.com. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b "Inauguration Weather: The Case of Kennedy". The Washington Post, Capital Weather Gang, January 5, 2009.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- ^ "North Korean official 'executed by flame-thrower'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ^ "Flamethrowers used to execute ISIS leaders in Tal Afar after their attempts to escape towards Syria fail". Iraqi News. 2016-08-23. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

General bibliography

[edit]- Clodfelter, Micheal (May 9, 2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th Ed. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 9780786474707. - Total pages: 824

- McNab, Chris (2015). The Flamethrower. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-1472809049.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 5, Part 7. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Wictor, Thomas (2010). Flamethrower Troops of World War I. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd (USA). ISBN 978-0764335266.

External links

[edit]- First World War.com: Weapons of War: Flamethrowers

- Fire Against the Enemy – The Flaming Bayonet for Trench Warfare

- Weapons of the World War II gyrene: Flamethrowers

- Howstuffworks "How Flamethrowers Work"

- Jaeger Platoon: Portable flame-throwers

- A history of flamethrowers

- Image of flamethrower in use

- Images, including a tank-mounted flamethrower's nozzle

- The Pen Huo Qi

- History and images of Australian flamethrowers

- WWII German army flamethrowers

- Modern Russian Flamethrowers, page in Russian

- USA-type flamethrower in use

- M42B1 Flamethrower Sherman Tank at U.S. Veterans Memorial Museum