Flag of India

| |

| Tiraṅgā (meaning "Tricolour") | |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 22 July 1947 |

| Design | A horizontal triband of India saffron, white, and India green; charged with a navy blue Ashoka Chakra with 24 spokes in the centre. |

| Designed by | Pingali Venkayya[N 1] |

| Red Ensign | |

| |

| Use | Civil ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Design | A red ensign with the Indian Flag in the canton |

| Blue Ensign | |

| |

| Use | State ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Design | A blue ensign with the Indian Flag in the canton, and a yellow anchor horizontally in the fly |

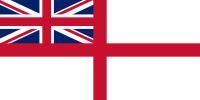

| White Ensign | |

| |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Design | A white ensign with the Indian Flag in the canton, and a blue octagon with golden borders encasing the national emblem atop an anchor superimposed on a shield with the naval motto "Śaṁ No Varuṇaḥ" in Devanagari in the fly |

| Air force Ensign | |

| |

| Use | Air force ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Design | A sky blue ensign with the Indian Flag in the canton and the Air Force roundel in the fly |

The national flag of India, colloquially called Tiraṅgā (the tricolour), is a horizontal rectangular tricolour flag, the colours being of India saffron, white and India green; with the Ashoka Chakra, a 24-spoke wheel, in navy blue at its centre.[1][2] It was adopted in its present form during a meeting of the Constituent Assembly held on 22 July 1947, and it became the official flag of the Union of India on 15 August 1947. The flag was subsequently retained as that of the Republic of India. In India, the term "tricolour" almost always refers to the Indian national flag.

The flag is based on the Swaraj flag, a flag of the Indian National Congress adopted by Mahatma Gandhi after making significant modifications to the design proposed by Pingali Venkayya.[3] This flag included the charkha which was replaced with the chakra in 1947 by Jawaharlal Nehru.[4]

Before the amendment of the flag code in 2021, the flag was by law only to be made of khadi; a special type of hand-spun cloth or silk, made popular by Mahatma Gandhi. The manufacturing process and specifications for the flag are laid out by the Bureau of Indian Standards. The right to manufacture the flag is held by the Khadi Development and Village Industries Commission, which allocates it to regional groups. As of 2023, there are 4 units in India that are licensed to manufacture the flag.

Usage of the flag is governed by the Flag Code of India and other laws relating to the national emblems. The original code prohibited use of the flag by private citizens except on national days such as the Independence day and the Republic Day. In 2002, on hearing an appeal from a private citizen, Naveen Jindal, the Supreme Court of India directed the Government of India to amend the code to allow flag usage by private citizens. Subsequently, the Union Cabinet of India amended the code to allow limited usage. The code was amended once more in 2005 to allow some additional use including adaptations on certain forms of clothing. The flag code also governs the protocol of flying the flag and its use in conjunction with other national and non-national flags.

History

Pre-independence movement

Civil Ensign of British India, 1880–1947

Civil Ensign of British India, 1880–1947A number of flags with varying designs were used in the period preceding the Indian independence movement by the rulers of different princely states; the idea of a single Indian flag was first raised by the British rulers of India after the rebellion of 1857, which resulted in the establishment of direct imperial rule. The first flag, whose design was based on western heraldic standards, was similar to the flags of other British colonies, including Canada and South Africa; its red field included the Union Jack in the upper-left quadrant and a Star of India capped by the royal crown in the middle of the right half. To address the question of how the star conveyed "Indianness", Queen Victoria created the Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India to honour services to the empire by her Indian subjects. Subsequently, all the Indian princely states received flags with symbols based on the heraldic criteria of Europe including the right to fly defaced British red ensigns.[5][6][7]

A proposed flag for India from 1904, as seen in an Anglo-Indian weekly. The dark blue band represented Hindus and Buddhists, the green band represented Muslims, and the light blue band represented Christians. The vertical purple band on the left side contained the stars from the Orion constellation, which represented the provinces and states. The surrounding red border symbolised India being kept united and whole by British rule.[8]

A proposed flag for India from 1904, as seen in an Anglo-Indian weekly. The dark blue band represented Hindus and Buddhists, the green band represented Muslims, and the light blue band represented Christians. The vertical purple band on the left side contained the stars from the Orion constellation, which represented the provinces and states. The surrounding red border symbolised India being kept united and whole by British rule.[8]In the early twentieth century, around the coronation of Edward VII, a discussion started on the need for a heraldic symbol that was representative of the Indian empire. William Coldstream, a British member of the Indian Civil Service, campaigned the government to change the heraldic symbol from a star, which he considered to be a common choice, to something more appropriate. His proposal was not well received by the government; Lord Curzon rejected it for practical reasons including the multiplication of flags.[9] Around this time, nationalist opinion within the realm was leading to a representation through religious tradition. The symbols that were in vogue included the Ganesha, advocated by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and Kali, advocated by Aurobindo Ghosh and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. Another symbol was the cow, or Gau Mata (cow mother). However, all these symbols were Hindu-centric and did not suggest unity with India's Muslim population.[10]

Early tricolour development

The Calcutta flag, design of the "Flag of Indian Independence" raised by Bhikaji Cama on 22 August 1907, at the International Socialist Conference in Stuttgart, Germany

The Calcutta flag, design of the "Flag of Indian Independence" raised by Bhikaji Cama on 22 August 1907, at the International Socialist Conference in Stuttgart, GermanyIn Europe, in 1579, during the Eighty Years' War, which established the independence of the Dutch Republic from the Spanish Empire, newly formed Netherlands adopted the first tricolour in the world, known as Prinsenvlag, an orange-white-blue flag. This flag symbolised independence. During the French Revolution, in 1790, Le Tricolore, a blue, white and red flag was adopted to symbolise republicanism (overthrow of monarchy). The flag of the Netherlands inspired the flag of France, which in turn inspired many further tricolour flags in countries around the world. Every country took to its own choice of colors to be represented in their tricolours.

The partition of Bengal (1905) resulted in the introduction of a new flag representing the Indian independence movement that sought to unite the multitude of castes and races within the country.

The Vande Mataram flag, part of the nationalist Swadeshi movement, comprised Indian religious symbols represented in western heraldic fashion. The tricolour flag included eight white lotuses on the upper green band representing the eight provinces, a sun and a crescent on the bottom red band, and the Vande Mataram slogan in Hindi on the central yellow band. The flag was launched in Calcutta bereft of any ceremony and the launch was only briefly covered by newspapers. The flag was not covered in contemporary governmental or political reports either but was used at the annual session of the Indian National Congress. A slightly modified version was subsequently used by Madam Bhikaji Cama at the second International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart in 1907. Despite the multiple uses of the flag, it failed to generate enthusiasm amongst Indian nationalists.[11]

Around the same time, another proposal for the flag was initiated by Sister Nivedita, a Hindu reformist and disciple of Swami Vivekananda. The flag consisted of a thunderbolt in the centre and a hundred and eight oil lamps for the border, with the Vande Mataram caption split around the thunderbolt. It was also presented at the Indian National Congress meeting in 1906.[12] Soon, many other proposals were initiated, but none of them gained attention from the nationalist movement.

In 1909, Lord Ampthill, former Governor of the Madras Presidency, wrote to The Times of London in the run-up to Empire Day pointing out that there existed "no flag representative of India as a whole or any Indian province... Surely this is strange, seeing that but for India there would be no Empire."[13]

Flag of the Indian Home Rule Movement adopted by Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Flag of the Indian Home Rule Movement adopted by Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar TilakIn 1916, Pingali Venkayya submitted thirty new designs, in the form of a booklet funded by members of the High Court of Madras. These many proposals and recommendations did little more than keep the flag movement alive. The same year, Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak adopted a new flag as part of the Home Rule Movement. The flag included the Union Jack in the upper left corner, a star and crescent in the upper right, and seven stars displayed diagonally from the lower right, on a background of five red and four green alternating bands. The flag resulted in the first governmental initiative against any nationalistic flag, as a magistrate in Coimbatore banned its use. The ban was followed by a public debate on the function and importance of a national flag.[14]

In the early 1920s, national flag discussions gained prominence across most British dominions following the peace treaty between Britain and Ireland. In November 1920, the Indian delegation to the League of Nations wanted to use an Indian flag, and this prompted the British Indian government to place renewed emphasis on the flag as a national symbol.

Gandhi's activism

In April 1921, Mahatma Gandhi wrote in his journal Young India about the need for an Indian flag, proposing a flag with the charkha or spinning wheel at the centre.[16] The idea of the spinning wheel was put forth by Lala Hansraj, and Gandhi commissioned Pingali Venkayya to design a flag with the spinning wheel on a red and green banner, the red colour signifying Hindus and the green standing for Muslims. Gandhi wanted the flag to be presented at the Congress session of 1921, but it was not delivered on time, and another flag was proposed at the session. Gandhi later wrote that the delay was fortuitous since it allowed him to realise that other religions were not represented; he then added white to the banner colours, to represent all the other religions. Finally, owing to the religious-political sensibilities, in 1929, Gandhi moved towards a more secular interpretation of the flag colours, stating that red stood for the sacrifices of the people, white for purity, and green for hope.[17]

On 13 April 1923, during a procession by local Congress volunteers in Nagpur commemorating the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, the Swaraj flag with the spinning wheel, designed by Pingali Venkayya, was hoisted. This event resulted in a confrontation between the Congressmen and the police, after which five people were imprisoned. Over a hundred other protesters continued the flag procession after a meeting. Subsequently, on the first of May, Jamnalal Bajaj, the secretary of the Nagpur Congress Committee, started the Flag Satyagraha, gaining national attention and marking a significant point in the flag movement. The satyagraha, promoted nationally by the Congress, started creating cracks within the organisation in which the Gandhians were highly enthused while the other group, the Swarajists, called it inconsequential.

Finally, at the All India Congress Committee meeting in July 1923, at the insistence of Jawaharlal Nehru and Sarojini Naidu, Congress closed ranks and the flag movement was endorsed. The flag movement was managed by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel with the idea of public processions and flag displays by common people. By the end of the movement, over 1500 people had been arrested across all of British India. The Bombay Chronicle reported that the movement drew from diverse groups of society including farmers, students, merchants, labourers and "national servants". While Muslim participation was moderate, the movement enthused women, who had hitherto rarely participated in the independence movement.[18]

While the flag agitation got its impetus from Gandhi's writings and discourses, the movement received political acceptance following the Nagpur incident. News reports, editorials and letters to editors published in various journals and newspapers of the time attest to the subsequent development of a bond between the flag and the nation. Soon, the concept of preserving the honour of the national flag became an integral component of the independence struggle. While Muslims were still wary of the Swaraj flag, it gained acceptance among Muslim leaders of the Congress and the Khilafat Movement as the national flag.

The Swaraj flag, officially adopted by the Indian National Congress in 1931

The Swaraj flag, officially adopted by the Indian National Congress in 1931Detractors of the flag movement, including Motilal Nehru, soon hailed the Swaraj flag as a symbol of national unity. Thus, the flag became a significant structural component of the institution of India. In contrast to the subdued responses of the past, the British Indian government took greater cognisance of the new flag and began to define a policy of response. The British parliament discussed public use of the flag, and based on directives from London, the British Indian government threatened to withdraw funds from municipalities and local governments that did not prevent the display of the Swaraj flag.[19] The Swaraj flag became the official flag of Congress at the 1931 meeting. However, by then, the flag had already become the symbol of the independence movement.[20]

Governor-General Louis Mountbatten's 1947 proposal for the flag of India, effectively the flag of the Congress but with a Union Jack in the canton. It was rejected by Jawaharlal Nehru, on the grounds that he felt that Congress' nationalist members would see the inclusion of the Union Jack as pandering to the British.[8]

Governor-General Louis Mountbatten's 1947 proposal for the flag of India, effectively the flag of the Congress but with a Union Jack in the canton. It was rejected by Jawaharlal Nehru, on the grounds that he felt that Congress' nationalist members would see the inclusion of the Union Jack as pandering to the British.[8]Final adoption

A few months before India gained its independence in August 1947, the Constituent Assembly was formed. To select a flag for independent India, on 23 June 1947, the assembly set up an ad hoc committee headed by Rajendra Prasad and including Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Sarojini Naidu, C. Rajagopalachari, K. M. Munshi and B. R. Ambedkar as its members.[21]

On 14 July 1947, the committee recommended that the flag of the Indian National Congress be adopted as the National Flag of India with suitable modifications, so as to make it acceptable to all parties and communities. It was also resolved that the flag should not have any communal undertones.[21] The spinning wheel of the Congress flag was replaced by the Ashoka Chakra from the Lion Capital of Ashoka. According to Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the chakra was chosen as it was representative of dharma and law. However, Jawaharlal Nehru explained that the change was more practical in nature, as unlike the flag with the spinning wheel, this design would appear symmetrical. Gandhi was not very pleased by the change, but eventually came around to accepting it.

The flag was proposed by Nehru at the Constituent Assembly on 22 July 1947 as a horizontal tricolour of deep saffron, white and dark green in equal proportions, with the Ashoka Chakra in blue in the centre of the white band. Nehru also presented two flags, one in Khadi-silk and the other in Khadi-cotton, to the assembly. The resolution was approved unanimously.[24] It served as the national flag of the Dominion of India between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950, and has served as the flag of the Republic of India since then.[25]

Timeline of official flags

State flags

Army flags

Navy flags

Air force flags

Civil and state ensigns

Design

Specifications

According to the Flag code of India, the Indian flag has a width:height aspect ratio of 3:2. All three horizontal bands of the flag (saffron, white and green) are equally sized. The Ashoka Chakra has twenty-four evenly spaced spokes.[21]

The size of the Ashoka Chakra is not specified in the flag code, but in section 4.3.1 of "IS1: Manufacturing standards for the Indian Flag", there is a chart that describes specific sizes of the flag and the chakra (reproduced alongside).[26]

| Flag size[27][28] | Width and height (mm) | Diameter of Ashoka Chakra (mm)[26] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6300 × 4200 | 1295 |

| 2 | 3600 × 2400 | 740 |

| 3 | 2700 × 1800 | 555 |

| 4 | 1800 × 1200 | 370 |

| 5 | 1350 × 900 | 280 |

| 6 | 900 × 600 | 185 |

| 7 | 450 × 300 | 90[29] |

| 8 | 225 × 150 | 40 |

| 9 | 150 × 100 | 25[29] |

Construction Sheets

Colours

Both the Flag code and IS1 call for the Ashoka Chakra to be printed or painted on both sides of the flag in navy blue.[26][21] Below is the list of specified shades for all colours used on the national flag, with the exception of navy blue, from "IS1: Manufacturing standards for the Indian Flag" as defined in the 1931 CIE Colour Specifications with illuminant C.[26] The navy blue colour can be found in the standard IS:1803–1973.[26]

| Colour | X | Y | Z | Brightness, Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India saffron | 0.538 | 0.360 | 0.102 | 21.5 |

| White | 0.313 | 0.319 | 0.368 | 72.6 |

| India green | 0.288 | 0.395 | 0.317 | 8.9 |

The values given in the table correspond to CIE 1931 colour space. Approximate RGB values for use may be taken to be: India saffron #FF671F, white #FFFFFF, India green #046A38, navy blue #06038D.[30] Pantone values closest to this are 165 C, White, 2258 C and 2735 C.

| Colour scheme | India saffron | White | India green | Navy blue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantone | 165 C | 000 C | 2258 C | 2735 C |

| CMYK | 0-60-88-0 | 0-0-0-0 | 96-0-47-58 | 96-98-0-45 |

| HEX | #FF671F | #FFFFFF | #046A38 | #06038D |

| RGB | 255,103,31 | 255,255,255 | 4,106,56 | 6,3,141 |

Symbolism

Gandhi first proposed a flag to the Indian National Congress in 1921. The flag was designed by Pingali Venkayya. In the centre was a traditional spinning wheel, symbolising Gandhi's goal of making Indians self-reliant by fabricating their own clothing, between a red stripe for Hindus and a green stripe for Muslims. The design was then modified to replace red with saffron and to include a white stripe in the centre for other religious communities (as well to symbolise peace between the communities) and provide a background for the spinning wheel. However, to avoid sectarian associations with the colour scheme, the three bands were later reassigned new meanings: courage and sacrifice, peace and truth, and faith and chivalry respectively.[31]

A few days before India became independent on 15 August 1947, the specially constituted Constituent Assembly decided that the flag of India must be acceptable to all parties and communities.[25] A modified version of the Swaraj flag was chosen; the tricolour remained the same saffron, white and green. However, the spinning wheel was replaced by the Ashoka Chakra representing the eternal wheel of law. The philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who later became India's first vice president and second president, clarified the adopted flag and described its significance as follows:

Bhagwa or the Saffron denotes renunciation or disinterestedness. Our leaders must be indifferent to material gains and dedicate themselves to their work. The white in the centre is light, the path of truth to guide our conduct. The green shows our relation to (the) soil, our relation to the plant life here, on which all other life depends. The "Ashoka Chakra" in the centre of the white is the wheel of the law of dharma. Truth or satya, dharma or virtue ought to be the controlling principle of those who work under this flag. Again, the wheel denotes motion. There is death in stagnation. There is life in movement. India should no more resist change, it must move and go forward. The wheel represents the dynamism of a peaceful change.[32]

Protocol

Correct horizontal and vertical display of the flag

Correct horizontal and vertical display of the flagDisplay and usage of the flag is governed by the Flag Code of India, 2002 (successor to the Flag Code – India, the original flag code); the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Improper Use) Act, 1950; and the Prevention of Insults to National Honor Act, 1971.[21] Insults to the national flag, including gross affronts or indignities to it, as well as using it in a manner so as to violate the provisions of the Flag Code, are punishable by law with imprisonment up to three years, or a fine, or both.[33]

Official regulation states that the flag must never touch the ground or water or be used as a drapery in any form.[21] The flag may not be intentionally placed upside down, dipped in anything, or hold any objects other than flower petals before unfurling. No sort of lettering may be inscribed on the flag.[27] When out in the open, the flag should always be flown between sunrise and sunset, irrespective of the weather conditions. Prior to 2009, the flag could be flown on a public building at night under special circumstances; currently, Indian citizens can fly the flag even at night, subject to the restriction that the flag should be hoisted on a tall flagpole and be well-illuminated.[21][34]

The flag should never be depicted, displayed or flown upside down. It is considered insulting to display the flag in a frayed or dirty state, and the same rule applies to the flagpoles and halyards used to hoist the flag, which should always be in a proper state of maintenance.[27]

The original flag code of India did not allow private citizens to fly the national flag except on national days such as Independence Day or Republic Day. In 2001, Naveen Jindal, an industrialist used to the more egalitarian use of the flag in the United States where he studied, flew the Indian flag on his office building. The flag was confiscated, and he was warned of prosecution. Jindal filed a public interest litigation petition in the High Court of Delhi; he sought to strike down the restriction on the use of the flag by private citizens, arguing that hoisting the national flag with due decorum and honour was his right as a citizen, and a way of expressing his love for the country.[35][36]

At the end of the appeals process, the case was heard by the Supreme Court of India; the court ruled in Jindal's favour, asking the Government of India to consider the matter. The Union Cabinet of India then amended the Indian Flag Code with effect from 26 January 2002, allowing private citizens to hoist the flag on any day of the year, subject to their safeguarding the dignity, honour and respect of the flag.[21] It is also held that the code was not a statute and restrictions under the code ought to be followed; also, the right to fly the flag is a qualified right, unlike the absolute rights guaranteed to citizens, and should be interpreted in the context of Article 19 of the Constitution of India.[21]

The original flag code also forbade use of the flag on uniforms, costumes and other clothing. In July 2005, the Government of India amended the code to allow some forms of usage. The amended code forbids usage in clothing below the waist and on undergarments, and forbids embroidering onto pillowcases, handkerchiefs or other dress material.[37]

Disposal of damaged flags is also covered by the flag code. Damaged or soiled flags may not be cast aside or disrespectfully destroyed; they have to be destroyed as a whole in private, preferably by burning or by any other method consistent with the dignity of the flag.[27]

Display

The rules regarding the correct methods to display the flag state that when two flags are fully spread out horizontally on a wall behind a podium, their hoists should be towards each other with the saffron stripes uppermost. If the flag is displayed on a short flagpole, this should be mounted at an angle to the wall with the flag draped tastefully from it. If two national flags are displayed on crossed staffs, the hoists must be towards each other, and the flags must be fully spread out. The flag should never be used as a cloth to cover tables, lecterns, podiums or buildings, or be draped from railings.[27]

Whenever the flag is displayed indoors in halls at public meetings or gatherings of any kind, it should always be on the right (observers' left), as this is the position of authority. So, when the flag is displayed next to a speaker in the hall or other meeting place, it must be placed on the speaker's right hand. When it is displayed elsewhere in the hall, it should be to the right of the audience. The flag should be displayed completely spread out with the saffron stripe on top. If hung vertically on the wall behind the podium, the saffron stripe should be to the left of the onlookers facing the flag with the hoist cord at the top.[27]

The flag, when carried in a procession or parade or with another flag or flags, should be on the marching right or alone in the centre at the front. The flag may form a distinctive feature of the unveiling of a statue, monument, or plaque, but should never be used as the covering for the object. As a mark of respect to the flag, it should never be dipped to a person or thing, as opposed to regimental colours, organisational or institutional flags, which may be dipped as a mark of honour. During the ceremony of hoisting or lowering the flag, or when the flag is passing in a parade or in a review, all persons present should face the flag and stand at attention. Those present in uniform should render the appropriate salute. When the flag is in a moving column, persons present will stand at attention or salute as the flag passes them. A dignitary may take the salute without a head dress. The flag salutation should be followed by the playing of the national anthem.[27]

The privilege of flying the national flag on vehicles is restricted to the President, the Vice President or the Prime Minister, Governors and Lieutenant Governors of states, Chief Ministers, Union Ministers, members of the Parliament of India and state legislatures of the Indian states (Vidhan Sabha and Vidhan Parishad), judges of the Supreme Court of India and High Courts, and flag officers of the Army, Navy and Air Force. The flag has to be flown from a staff affixed firmly either on the middle front or to the front right side of the car. When a foreign dignitary travels in a car provided by government, the flag should be flown on the right side of the car while the flag of the foreign country should be flown on the left side.[27]

The flag should be flown on the aircraft carrying the President, the Vice President or the Prime Minister on a visit to a foreign country. Alongside the National Flag, the flag of the country visited should also be flown; however, when the aircraft lands in countries en route, the national flags of the respective countries would be flown instead. When carrying the president within India, aircraft display the flag on the side the president embarks or disembarks; the flag is similarly flown on trains, but only when the train is stationary or approaching a railway station.[27]

When the Indian flag is flown on Indian territory along with other national flags, the general rule is that the Indian flag should be the starting point of all flags. When flags are placed in a straight line, the rightmost flag (leftmost to the observer facing the flag) is the Indian flag, followed by other national flags in alphabetical order. When placed in a circle, the Indian flag is the first point and is followed by other flags alphabetically. In such placement, all other flags should be of approximately the same size with no other flag being larger than the Indian flag. Each national flag should also be flown from its own pole and no flag should be placed higher than another. In addition to being the first flag, the Indian flag may also be placed within the row or circle alphabetically. When placed on crossed poles, the Indian flag should be in front of the other flag, and to the right (observer's left) of the other flag. The only exception to the preceding rule is when it is flown along with the flag of the United Nations, which may be placed to the right of the Indian flag.[27]

When the Indian flag is displayed with non-national flags, including corporate flags and advertising banners, the rules state that if the flags are on separate staffs, the flag of India should be in the middle, or the furthest left from the viewpoint of the onlookers, or at least one flag's breadth higher than the other flags in the group. Its flagpole must be in front of the other poles in the group, but if they are on the same staff, it must be the uppermost flag. If the flag is carried in procession with other flags, it must be at the head of the marching procession, or if carried with a row of flags in line abreast, it must be carried to the marching right of the procession.[27]

Half-mast

The flag should be flown at half-mast as a sign of mourning. The decision to do so lies with the president of India, who also decides the period of such mourning. When the flag is to be flown at half mast, it must first be raised to the top of the mast and then slowly lowered. Only the Indian flag is flown half mast; all other flags remain at normal height.

The flag is flown half-mast nationwide on the death of the president, vice president or prime minister. It is flown half-mast in New Delhi and the state of origin for the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and Union Ministers. On deaths of governors, lieutenant governors and chief ministers, the flag is flown at half-mast in the respective states and union territories.

The Indian flag cannot be flown at half-mast on Republic Day (26 January), Independence day (15 August), Gandhi Jayanti (2 October), or state formation anniversaries, except over buildings housing the body of the deceased dignitary. However, even in such cases, the flag must be raised to full-mast when the body is moved from the building.

Observances of State mourning on the death of foreign dignitaries are governed by special instructions issued from the Ministry of Home Affairs in individual cases. However, in the event of death of either the Head of the State or Head of the Government of a foreign country, the Indian Mission accredited to that country may fly the national flag at half-mast.

On occasions of state, military, central para-military forces funerals, the flag shall be draped over the bier or coffin with the saffron towards the head of the bier or coffin. The flag should not be lowered into the grave or burnt in the pyre.[27]

Manufacturing process

The design and manufacturing process for the national flag is regulated by three documents issued by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). All of the flags are made out of khadi cloth of silk or cotton. The standards were created in 1968 and were updated in 2008.[38] Nine standard sizes of the flag are specified by law.[27]

In 1951, after India became a republic, the Indian Standards Institute (now the BIS) brought out the first official specifications for the flag. These were revised in 1964 to conform to the metric system which was adopted in India. The specifications were further amended on 17 August 1968.[21] The specifications cover all the essential requirements of the manufacture of the Indian flag including sizes, dye colour, chromatic values, brightness, thread count and hemp cordage. The guidelines are covered under civil and criminal laws and defects in the manufacturing process can result in punishments that include fines or jail terms.[39][40]

Until 2021, Khadi or hand-spun cloth was the only material allowed to be used for the flag, and flying a flag made of any other material was punishable by law with imprisonment up to three years, besides a fine (although this was rarely enforced). Raw materials for khadi are restricted to cotton, silk and wool. There are two kinds of khadi used: The first is the khadi-bunting which makes up the body of the flag, and the second is the khadi-duck, which is a beige-coloured cloth that holds the flag to the pole. The khadi-duck is an unconventional type of weave that meshes three threads into a weave, compared to the two threads used in conventional weaving. This type of weaving is extremely rare, and there are fewer than twenty weavers in India professing this skill. The guidelines also state that there should be exactly 150 threads per square centimetre, four threads per stitch, and one square foot should weigh exactly 205 grams (7.2 oz).[21][39][40][41]

The woven khadi is obtained from two handloom units in the Dharwad and Bagalkot districts of northern Karnataka. As of 2022[update], there are four BIS flag production and supply units; namely Karnataka Khadi Gramodyoga Samyukta Sangha based in Hubli, Khadi Dyers & Printers (also known as Kore Gramodyog Kendra) based in Borivali, KDP Enterprises based in Vasai, and the Madhya Bharat Khadi Sangh based in Gwalior.[42][43][44][45][46] The unit in Gwalior in particular has a laboratory for testing the standard of the Khadi cloth used for making the flags.

Permission for setting up flag manufacturing units in India is allotted by the Khadi Development and Village Industries Commission, though the BIS has the power to cancel the licences of units that flout guidelines.[21] [40] The hand-woven khadi for the National Flag was initially manufactured at Garag, a small village in the Dharwad district. A Centre was established at Garag in 1954 by a few freedom fighters under the banner of Dharwad Taluk Kshetriya Seva Sangh and obtained the centre's licence to make flags.[21]

Once woven, the material is sent to the BIS laboratories for testing. After quality testing, the material, if approved, is returned to the factory. It is then separated into three lots which are dyed saffron, white and green. The Ashoka Chakra is screen printed, stencilled or suitably embroidered onto each side of the white cloth. Care also has to be taken that the chakra is completely visible and synchronised on both sides. Three pieces of the required dimension, one of each colour, are then stitched together according to specifications and the final product is ironed and packed. The BIS then checks the colours and only then can the flag be sold.[39][40]

In December 2021 the Government of India amended the flag code to allow machine manufacturing of flags as well as the use of alternative materials including polyester, non-khadi cotton or silk.[47]

See also

- Tiranga Point

- Indian Naval Ensign

- Jana Gana Mana

- Largest Human Flag of India

- List of Indian flags

- List of Indian state flags

- National Pledge

- Satyameva Jayate

- National Emblem of India

- Vande Mataram

Notes

- ^ The current flag is an adaptation of Venkayya's original design, but he is generally credited as the designer of the flag.

References

- ^ "National Symbols". www.india.gov.in. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "National Identity Elements - National Flag". knowindia.india.gov.in. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Kapoor, P. (2018). Gandhi: An Illustrated Biography (in Maltese). Roli Books. p. 121. ISBN 978-81-936009-1-7. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Goucher, C.; Walton, L. (2013). World History: Journeys from Past to Present. Taylor & Francis. p. 667. ISBN 978-1-135-08828-6.

- ^ Virmani 1999, p. 172

- ^ Roy 2006, p. 498

- ^ Volker Preuß. "British Raj Marineflagge" (in German). Archived from the original on 17 September 2005. Retrieved 4 September 2005.

- ^ Virmani 1999, p. 173

- ^ Virmani 1999, p. 174

- ^ Virmani 1999, pp. 175–176

- ^ Roy 2006, pp. 498–499

- ^ "A Flag for India". Luton Times and Advertiser. 21 May 1909. Retrieved 27 August 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Virmani 1999, pp. 176–177

- ^ Roy 2006, p. 504

- ^ Virmani 1999, pp. 177–178

- ^ Roy 2006, pp. 503–505

- ^ Virmani 1999, pp. 181–186

- ^ Virmani 1999, pp. 187–191

- ^ Roy 2006, p. 508

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Flag code of India, 2002". Fact Sheet. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 4 April 2002. Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ^ India Postage Stamps 1947–1988.(1989) Philately branch, Department of Posts, India.

- ^ Souvenir sheet of the Independence series of stamps, Indian Posts, 1948

- ^ Jha 2008, pp. 106–107

- ^ a b Heimer, Željko (2 July 2006). "India". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Bureau of Indian Standards (1968). IS 1 : 1968 Specification for the national flag of India (cotton khadi). Government of India. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Flag Code of India". Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 25 January 2006. Archived from the original on 10 January 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ^ "IS 1 (1968): Specification for The National Flag of India (Cotton Khadi, PDF version)" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b Bureau of Indian Standards (1979). IS 1 : 1968 Specification for the national flag of India (cotton khadi), Amendment 2. Government of India.

- ^ Wikipedia articles for the respective colour names

- ^ "Flag of India". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^ "Flag Code of India, 2002". Press Information Bureau. Government of India. 3 April 2002. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ "The Prevention of Insults To National Honour Act, 1971" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Press Trust of India (24 December 2009). "Now, Indians can fly Tricolour at night". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "My Flag, My Country". Rediff.com. 13 June 2001. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ "Union of India v. Navin Jindal". Supreme Court of India. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- ^ Chadha, Monica (6 July 2005). "Indians can wear flag with pride". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ "Indian Standards" (PDF). Bureau of Indian Standards. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ a b c Vattam, Shyam Sundar (15 June 2004). "Why all national flags will be 'Made in Hubli'". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d Aruna Chandaraju (15 August 2004). "The Flag Town". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ Chandaraju, Aruna (15 August 2004). "The flag town". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Specification for the national flag of India (Cotton khadi)". Bureau of Indian Standards. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Nitin Sreedhar (14 August 2016). "The tricolour story". The Financial Express. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "ग्वालियर खादी संघ बना रहा 4 गुना राष्ट्रीय ध्वज, पूरे देश में यहीं से होते हैं तिरंगे सप्लाई". zeenews.india.com (in Hindi). 30 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Manish Upadhyay (6 August 2022). "Indore: Amendment in Flag-Code made National Flag affordable, price came down from Rs 700 to Rs 25 per piece". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Tiranga of Gwalior: Tricolor made in Gwalior hoisted in half of the country". pipanews.com. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Har Ghar Tiranga: National flag can now be machine-made, in polyester". The Business Standard. 1 June 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

Cited Sources

- Virmani, Arundhati (2008). A National Flag for India: Rituals, Nationalism and the Politics of Sentiment. Delhi, Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-232-3.

- Virmani, Arundhati (August 1999). "National Symbols under Colonial Domination: The Nationalization of the Indian Flag, March–August 1923". Past & Present (164): 169–197. doi:10.1093/past/164.1.169. JSTOR 651278..

- Roy, Srirupa (August 2006). "A Symbol of Freedom: The Indian Flag and the Transformations of Nationalism, 1906–". Journal of Asian Studies. 65 (3). ISSN 0021-9118. OCLC 37893507.

- Jha, Sadan (25 October 2008). "The Indian National Flag as a site of daily plebiscite". Economic and Political Weekly: 102–111. ISSN 0012-9976. OCLC 1567377.

- "Indian Standards" (PDF). Bureau of Indian Standards. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- "India". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2005.

- "India: Historical Flags". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2005.

- "Flying the real tricolour". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- "My Flag, My Country". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- Royle, Trevor (1997). The Last Days of the Raj. John Murray. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7195-5686-9.

External links

- "National Flag". National Portal of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- "History of Indian Tricolour". National Portal of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Flag Code of India" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs (India). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- India at Flags of the World