Early history of the IRT subway

The first regularly operated line of the New York City Subway was opened on October 27, 1904, and was operated by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). The early IRT system consisted of a single trunk line running south from 96th Street in Manhattan (running under Broadway, 42nd Street, Park Avenue, and Lafayette Street), with a southern branch to Brooklyn. North of 96th Street, the line had three northern branches in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. The system had four tracks between Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall and 96th Street, allowing for local and express service. The original line and early extensions consisted of:

- The IRT Eastern Parkway Line from Atlantic Avenue–Barclays Center to Borough Hall

- The IRT Lexington Avenue Line from Borough Hall to Grand Central–42nd Street

- The IRT 42nd Street Shuttle from Grand Central–42nd Street to Times Square

- The IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line from Times Square to Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street

- The IRT Lenox Avenue Line from 96th Street to 145th Street

- The IRT White Plains Road Line from 142nd Street Junction to 180th Street–Bronx Park

Planning for a rapid transit line in New York City started in 1894 with the enactment of the Rapid Transit Act. The plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission. The city government started construction on the first IRT subway in 1900, leasing it to the IRT for operation under Contracts 1 and 2. After the initial line was opened, several modifications and extensions were made in the 1900s and 1910s.

The designs of the underground stations are inspired by those of the Paris Métro; with few exceptions, Parsons's team designed two types of stations for Contracts 1 and 2. Many stations were built just below or above street level, as Parsons wished to avoid using escalators and elevators as the primary means of access to the station. Heins & LaFarge designed elaborate decorative elements for the early system, which varied considerably between each station, and they were also responsible for each station's exits and entrances. Most tunnels used cut-and-cover construction, although deep-level tubes were used in parts of the system; elevated structures were used in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. The lines used third rail power supplied by the IRT Powerhouse, as well as rolling stock made of steel or of steel–wood composite.

The city could only afford one subway line in 1900 and had hoped that the IRT would serve mainly to relieve overcrowding on the existing transit system, but the line was extremely popular, accommodating 1.2 million riders a day by 1914. Although the subway had little impact on retail in Lower and Midtown Manhattan, the completion of the IRT subway helped encourage other development, including residential growth in outlying areas and the relocation of Manhattan's Theater District. The Dual Contracts, signed in 1913, provided for the expansion of the subway system; as part of the Dual Contracts, a new H-shaped system was placed in service in 1918, splitting the original line into several segments. Most of the original IRT continues to operate as part of the New York City Subway, but several stations have been closed.

History

[edit]

Earlier plans

[edit]The New York State Legislature granted a charter to the New York City Central Underground Company to give it power to construct a subway line in 1868. However, the charter made it impossible for the company to raise adequate money to fund the line's construction. Cornelius Vanderbilt and some associates had the New York City Rapid Transit Company chartered in 1872 to build an underground line from Grand Central station to City Hall as an extension of the Park Avenue main line.[1]: 104 The line would have run from Broadway's east side at City Hall Park east to Chatham or Centre Street, then to Park Street, Mott Street, the Bowery, Third Avenue, and Fourth Avenue to connect with the existing line between 48th Street and 59th Street. The line was estimated to cost $9.1 million.[2]

While Cornelius Vanderbilt had indicated his intent to continue the underground line to City Hall, there was speculation that he did not intend to build the section south of 42nd Street. William Henry Vanderbilt stated the line would not be as dark as the Metropolitan Railway (now part of the London Underground), and that there would be stations every eight blocks, or every .5 miles (0.80 km). In January 1873, he expected the cost of the work to City Hall to be $8 to $10 million, and that the whole project would be completed by January 1, 1875.[3] The line was expected to have 400,000 daily passengers, and trains would have traversed the line from City Hall to Grand Central in twelve minutes, and from there to the Harlem River in ten minutes.[4] Although plans and surveys for the line were completed by January 1873, and proposals for the project were being received,[5] Vanderbilt elected not to follow through on the project due to public criticism for the grant, opposition to the project[1]: 104 from business people and homeowners in the Bowery and due to the Panic of 1873.[6]: 82 [7]

The State Legislature granted other applications for the incorporation of companies to construct a subway in New York, including the Arcade Railroad, which would have been built by the Beach Pneumatic Railroad Company. Since none of these companies could obtain enough capital to fund construction, proposals to construct a subway line died by 1875. That year, the Rapid Transit Act of 1875 was passed, allowing for the construction of multiple elevated rail lines in the city, which reduced demand for a subway line until 1884.[6]: 82 In 1874, the New York State Legislature passed a bill allowing for the creation of a rapid transit commission in New York City, which was formed in 1875.[8][9]

In April 1877, the New York City Board of Alderman passed a resolution requesting that Commissioner Campbell assess the feasibility of constructing an underground line from City Hall to the existing line by private enterprise. The Commissioner was strongly in support of such a plan, and predicted that such a line would have a daily ridership of 100,000, would make $1.8 million annually and would cost $9 to $10 million to build–in his mind, a financial success.[10] William Vanderbilt was criticized for not following through on the plans of his father to extend the line to City Hall.[11]

In 1880, the New York Tunnel Railway was incorporated to construct a railroad from Washington Square Park under Wooster Street and University Street to 13th Street, and then under Fourth Avenue and 42nd Street to connect to the Fourth Avenue Improvement.[12] On October 2, 1895, the Central Tunnel Company, the New-York and New-Jersey Tunnel Railroad Company, and the Terminal Underground Railroad Company of New York were consolidated into the Underground Railroad Company of the City of New York. Together, they planned to build a line running from City Hall Park to the Fourth Avenue Improvement. The line would have run north under Chambers Street and Reade Street, before going up Elm Street to Spring Street, Marion Street and Mulberry Streets, before continuing through blocks and Great Jones Street, Lafayette Place, Astor Place and Eighth Street, and then under Ninth Street to Fourth Avenue, before heading under 42nd Street to Grand Central Depot to connect with the Fourth Avenue Improvement. The line would have had three connecting branches.[13]

In January 1888, Mayor Abram Hewitt, in his message to the New York City Common Council, conveyed his belief that a subway line could not be built in New York City without the use of credit from the city government, and that if city funding were used, the city should own the subway line. He stated that a private company would likely be needed to undertake the construction of the line, and would have to provide a sufficient bond to complete the work to protect the city against loss. Hewitt said that the company would be able to operate the line, but would need to do so under rent, which would pay off the interest on the city bonds used to finance the construction of the line, and a sinking fund to pay off the payment of the bonds. Furthermore, the company should fund the real estate needed for buildings, such as power houses, the rolling stock to operate subway service, and a fund to protect the city against losses if the company failed to build and operate the subway line. Though the Mayor in the message also suggested encouraging the New York Central Railroad to construct and operate a subway line, the company was unwilling to start such a venture. Legislation was drafted and submitted to the State Legislature in 1888 to allow for competition among companies and people willing to start work on a subway line. However, due to opposition from the Common Council, and Tammany Hall, it was hard to find any legislator to sponsor the bill. The bill failed after the Committee of the Legislature elected not to report the bill back to the New York State Senate.[6]: 82–83

New mayor Hugh J. Grant appointed a five-member Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners in April 1889 to lay out planned subway lines across the city.[8] The Board held its first meeting on April 23, 1890, and elected August Belmont as its President. The Board sent a letter to Mayor Grant on June 20, telling him that state law made it illegal to construct a rail line on many streets in the city, making it impossible to provide routes for a subway line that would benefit the public. The Board later adopted a route that would avoid these restrictions, with the section of the route between 42nd Street and City Hall being identical to the route of the first subway line that would be built.[6]: 83

As a result of the worsening transportation situation in the city, and requests for action by the public, the State Legislature passed the Rapid Transit Act of 1891, allowing all cities with a population of over one million, of which New York City was the only one, to create a board of "rapid transit railroad commissioners." This Board would determine whether it was necessary to build a rapid transit system, and if this were the case, would adopt a route for the construction of a railroad and obtain permission for its construction from local authorities, and local property owners, or from the General Term of the New York Supreme Court. The Board would then approve detailed plans for the operation and construction of the railroad and sell the right to operate and construct the rail line. The government could issue bonds in order to fund rapid transit for the city.[14][15][16] The year, a five-member rapid transit board for the city, called the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners, was appointed. After a series of hearings, it unanimously concluded that a rapid transit system was needed in New York City and that it should be completed through an underground system. The board released a plan for a mostly underground rapid transit line on October 20, 1891, and obtained consent from local authorities and the General Term of the New York Supreme Court. The Board adopted detailed plans for the railroad, and opened bidding for the contract on December 29, 1892. While it received bids for the municipal rail line, no bids were selected as no responsible bidder was willing to take on the project.[8] Following this failed attempt, the plan was essentially scrapped, and the Board lacked the power to act further.[6]: 83–84

As a result of this failure, a proposition was made requesting that the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York construct a subway system if New York City loaned it money to undertake the work. A committee of the most influential members of the Chamber came out in support of the proposition, but former Mayor Hewitt stated it was not wise to present the public with a proposal in which public money would be used by the private sector. Hewitt's opinion was unanimously approved by the Chamber of Commerce, and a new committee was created to write a bill, based in part on the legislation Hewitt proposed in 1888, to submit to the State Legislature.[6]: 83

Planning

[edit]The new bill, known as the Rapid Transit Act of 1894, was signed into law on May 22, 1894, creating a new Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners, which included the Mayor of New York City. Planning for the system that was built began with this law.[8] The act provided that the commission would lay out routes with the consent of property owners and local authorities, either build the system or sell a franchise for its construction, and lease it to a private operating company for fifty years.[17]: 139–161 The law made it possible for the city to own the rapid transit system, and therefore borrow money to fund its construction. It also expected the new Board to continue the work of the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners from the 1891 law.[6]: 83

The subway plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission. It called for a subway line from New York City Hall in lower Manhattan to the Upper West Side, where two branches would lead north into the Bronx.[18]: 3 As part of the project, Parsons investigated other cities' transit systems to determine features that could be used in the new subway.[19] Later in 1894, voters approved by referendum a city policy that future rapid transit lines should be operated by the city instead of franchised to private operators.[14]: 1

A line through Lafayette Street (then Elm Street) to Union Square was considered, but at first, a more costly route under lower Broadway was adopted. A legal battle with property owners along the route led to the courts denying permission to build through Broadway in 1896. The Elm Street route was chosen later that year, cutting west to Broadway via 42nd Street. This new plan, formally adopted on January 14, 1897, consisted of a line from City Hall north to Kingsbridge and a branch under Lenox Avenue and to Bronx Park, to have four tracks from City Hall to the junction at 103rd Street. The "awkward alignment...along Forty-Second Street", as the commission put it, was necessitated by objections to using Broadway south of 34th Street. Legal challenges were finally taken care of near the end of 1899.[17]: 139–161 Elm Street would be widened and cut through from Centre Street and Duane Street to Lafayette Place to provide a continuous thoroughfare for the subway to run under.[20]: 227

Construction

[edit]Contract awards

[edit]On November 15, 1899, contract for the construction of the subway and for its operation were advertised. It called for a line beginning with a loop at Broadway and Park Row around the General Post Office, before continuing as a four-track line via Park Row, Centre Street, Elm Street, Lafayette Place, Fourth Avenue, 42nd Street and Broadway to 103rd Street. Then the line would diverge, with a western branch running under Broadway to Fort George before continuing via a viaduct over Ellwood Street and Kingsbridge Road to Bailey Avenue.[21] The intermediate section would be largely underground, except for the Manhattan Valley Viaduct between 122nd Street and 135th Street, which would cross a deep valley there.[22] The eastern branch was to run under private property to 104th Street, under that street, Central Park, Lenox Avenue, the Harlem River and 149th Street. At Third Avenue, the line would emerge onto a viaduct, continuing over Westchester Avenue, Southern Boulevard and Boston Road to Bronx Park. Both branches were to be two-track lines. Bids were opened on January 15, 1900, and the contract, later known as Contract 1, was executed on February 21, 1900,[21] between the commission and the Rapid Transit Construction Company, organized by John B. McDonald and funded by August Belmont Jr., for the construction of the subway and a 50-year operating lease from the opening of the line.[17]: 162–191 As part of the agreement, $35 million would be provided for the total cost of the line, and the Rapid Transit Construction Company would provide the cost of necessary equipment, including signals, rolling stock, and power plants. A formal groundbreaking ceremony was done City Hall on March 24, pursuant to the contract's requirements.[17]: 162–191 [21]

Shortly afterwards, the Rapid Transit Construction Company began preparing for the actual construction of the line, divided the route up into fifteen sections, and invited bids from subcontractors for each of these segments.[21][23]: 235 Degnon-McLean Contracting Company was awarded the contract for Section 1, from Post Office Loop to Chambers Street, and the contract for section 2, from Chambers Street to Great Jones Street. Work began on Section 1 on March 24, 1900, and work began on Section 2 on July 10, 1900. On May 14, 1900, L. B. McCabe & Brother commenced work on Section 13, the segment between 133rd Street and a point 100 feet (30 m) north of 182nd Street. Construction began on the section from 104th Street to 125th Street on June 18, 1900. Work on this section, Section 11 was awarded to John Shields. Work began on Section 6A, from 60th Street to 82nd Street, and for Section 6B, from 82nd Street to 104th Street, on August 22, 1900. These sections had been awarded to William Bradley. Construction on the portion from 110th Street to a point 100 feet (30 m) north of 135th Street, Section 8, was begun on August 30, 1900, by Farrell & Hopper. On September 12, 1900, work began on the line from Great Jones Street and 41st Street. The first section, from Great Jones Street to a point 100 feet (30 m) north of 33rd Street, Section 3, had been awarded to Holbrook, Cabot & Daly Contracting Company, while the remaining section to 41st Street, Section 4 was to be done by Ira A. Shaler. A week later, on September 19, Naughton & Company began work on Section 5-B, which stretched from 47th Street to 60th Street. On October 2, 1900, Farrell & Hopper started work on Section 7, from 103rd Street to 110th Street and Lenox Avenue.[21]

Degnon-McLean began work on the section along Park Avenue from 41st Street and 42nd Street, along 42nd Street, and then Broadway to 47th Street, Contract 5-A, on February 25, 1901. Construction was begun on Section 14, the portion for a point 100 feet (30 m) north of 182nd Street to Hillside Avenue, by L. B. McCabe & Brother on March 27, 1901. On June 1, 1901, work began on the viaduct over Manhattan Valley from 125th Street to 133rd Street, Section 12. Work on the stone piers and foundations for the viaduct was done by E. P. Roberts, while other work was done by Terry & Tench Construction Company. Work on Section 9-B, between Gerard Avenue on 149th Street and a point past Third Avenue where the viaduct begins, was started on June 13, 1901, by J.C. Rogers. Work on Section 11, from 104th Street to 135th Street, which had been awarded to John Shields, began on June 18, 1901. On August 19, 1901, E. P. Roberts and Terry & Tench Construction Company began work on Section 10, from Brook Avenue to Bronx Park and 182nd Street. McMullan & McBean began work on the section from 135th Street and Lenox Avenue to Gerard Avenue and 149th Street, Section 9-A, on September 10, 1901. Work began on the final section, the West Side Viaduct from Hillside Avenue to Bailey Avenue, Section 15 on January 19, 1903. E. P. Roberts and Terry & Tench Construction Company completed this work.[21] In addition, contracts for 74,326 tons of structural steel and 4,000 tons of rail were awarded to the Carnegie Steel Company. United Building Materials Company was to supply 1.5 million barrels of cement, which would be used to make 400,000 cubic yards of concrete. These were said to be "the largest ever undertaken by an individual firm for supplying cement and steel for a single engineering work".[23]: 236

On February 26, the Board instructed the Chief Engineer to evaluate the feasibility of extending the subway south to South Ferry, and then to Brooklyn. To ensure that the RTC was legally permitted to construct the subway into areas of the city that were added as part of Consolidation in 1898, which occurred after the Act of 1894 was passed, a bill was passed and became law on April 23, 1900. In May 1900, two routes were examined for the Brooklyn extension. One route would have run under Broadway to Whitehall Street, under the East River, Joralemon Street, Fulton Street, and Flatbush Avenue to Atlantic Avenue. The second route would have followed the first route but would have gone to Hamilton Avenue before going towards Bay Ridge and South Brooklyn. On January 24, 1901, the Board adopted the first route, which would extend the subway 3.1 miles (5.0 km) from City Hall to the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s Flatbush Avenue terminal station (now known as Atlantic Terminal) in Brooklyn. The line's cost was expected to be no greater than $8 million, and added 8 miles (13 km) of trackage.[20]: 83–84 Two contracts were received to construct the line and its terminals. John L. Wells of the Brooklyn Rapid Railroad Company submitted a bid of $1 million for terminals, and $7 million for construction, while the Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company, which completed Contract 1, bid $1 million for terminals, and $2 million for construction. As such,Contract 2, giving a lease of only 35 years, was executed between the commission and the Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company on September 11, with construction beginning at State Street in Manhattan on November 8, 1902.[4] Belmont incorporated the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in April 1902 as the operating company for both contracts; the IRT leased the Manhattan Railway Company, operator of the four elevated railway lines in Manhattan and the Bronx, on April 1, 1903.[17]: 162–191

Progress

[edit]On July 12, 1900, the contract was modified to widen the subway at Spring Street to allow for the construction of 600 feet (183 m) of a fifth track, and to lengthen express station platforms to 350 feet (107 m) to accommodate longer trains.[20]: 82, 249 On June 21, 1900, the route of Contract 1 was modified at Fort George in Upper Manhattan. The route was changed to run over Nagle Avenue and Amsterdam Avenue instead of over Ellwood Street, between Eleventh Avenue and Kingsbridge Avenue or Broadway. The route of the terminal loop at City Hall was shortened to only be constructed between City Hall and the Post Office instead of passing completely around the Post Office as a result of a change issued on January 10, 1901.[24]: 189–190 In addition, the loop was changed from being double-tracked to single tracked. The loop was designed to allow local trains to be turned around, and to pass under the express tracks under Park Row without an at-grade crossing, and to allow for a possible future extension south under Broadway. To allow for the switching back of express trains, a relay track was constructed under Park Row, allowing for a future southern extension under Broadway.[20]: 226, 249

On December 20, 1900, the contractor requested that the plans for the Manhattan Valley Viaduct be modified to allow for a three-track structure and for the construction of a third track at the 145th Street, 116th Street, and 110th Street stations. The Board adopted the request on January 24, 1901. Some time after, the contractor requested permission to construct a third track for storage. The Board authorized the construction of a third track from 103rd Street to 116th Street on March 7, 1901. The contractor petitioned the board once more for the permission to build a third track continuously from 137th Street to 103rd Street, some of which was already authorized, and to build a storage yard between 137th Street and 145th Street, with three tracks on either side of the main line to allow for the storage of 150 cars. The Board authorized the request on May 2, 1901, and rescinded the March 7 resolution. The new resolution specified that the third track would be for express trains.[20]: 93 [24]: 189–190 However, construction on the section between 104th Street and 125th Street had already begun prior to the design change, requiring that a portion of the work be undone.[20]: 240–241 As part of the modifications for a third track, a third track was to be added to both the upper and lower levels of the subway directly north of 96th Street, immediately to the east of the originally planned two tracks.[25]: 14

In 1902, the contractor requested permission to build an additional third track from Fort George to Kingsbridge. The Board authorized the construction of the track on January 15, 1903,[26]: 35 and it was formally approved on March 24, 1904.[24]: 191

The contractor for the subway purchased a large area of land on the Harlem River near 150th Street for the construction of a terminal for the East Side Line. On October 24, 1901, the Board voted to extend the line from 143rd Street to the terminal. As part of the plan, a station would be built at 145th Street instead of at 141st Street and Lenox Avenue.[27]: 781 Some trains would originate at 145th Street instead of Bronx Park. This change was expected to promote the benefits of using the subway for travel to Harlem.[20]: 94 On April 28, 1902, Mayor Low signed the ordinance providing for the extension.[28] On January 16, 1903, a modification to Contract 1 was made to allow for the extension of the Lenox Avenue Line from 142nd Street to 148th Street with a stop between 142nd Street and Exterior Street. The stop was placed at 145th Street along tracks that were only intended to lead to Lenox Yard.[29][30]: 387–415

Also in 1903, residents in the vicinity of 104th Street and Central Park West urged the board to build a station at this location. They cited the long distance between the two nearest subway stations, and the need to serve Central Park West. The Board declined to construct the station after serious consideration. They found that the station's construction would have delayed the opening of the line, and would have slowed service for passengers using the Lenox Avenue Line coming from the Bronx.[26]: 43 Residents of the area requested the construction of a station at this location again in 1921.[31]

The soil excavated during construction went to various places.[32] In particular, Ellis Island in New York Harbor was expanded from 2.74 acres (1.11 ha) to 27.5 acres (11.1 ha), partially with soil from the excavation of the IRT line,[33] while nearby Governors Island was expanded from 69 acres (28 ha) to 172 acres (70 ha).[34] The excavated Manhattan schist was also used to construct buildings for the City College of New York.[32]

Opening

[edit]

On New Year's Day 1904, mayor George B. McClellan Jr. and a group of wealthy New Yorkers gathered at the City Hall station and traveled 6 miles (9.7 km) to 125th Street using handcars.[35][36] The IRT conducted several more handcar trips afterward. The first train to run on its own power traveled from 125th Street to City Hall in April 1904.[37]

Operation of the subway began on October 27, 1904,[38] with the opening of all stations from City Hall to 145th Street on the West Side Branch.[17]: 162–191 [24]: 189 Express trains originally were eight cars long.[4] Service was extended to 157th Street for a football game on November 12, 1904, before the station had fully opened. The 157th Street station officially opened on December 4.[24]: 191 On November 23, 1904, the East Side Branch, or Lenox Avenue Line, opened to 145th Street.[24]: 191 The line was extended to Fulton Street on January 16, 1905,[39] to Wall Street on June 12, 1905,[40] and to Bowling Green and South Ferry on July 10, 1905.[41]

The initial segment of the IRT White Plains Road Line opened on November 26, 1904, between Bronx Park/180th Street and Jackson Avenue. Initially, trains on the line were served by elevated trains from the IRT Second Avenue Line and the IRT Third Avenue Line, with a connection running from the Third Avenue local tracks at Third Avenue and 149th Street to Westchester Avenue and Eagle Avenue. Once the connection to the IRT Lenox Avenue Line opened on July 10, 1905, trains from the newly opened IRT subway ran via the line.[42] Elevated service on the White Plains Road Line via the Third Avenue elevated connection was resumed on October 1, 1907, when Second Avenue locals were extended to Freeman Street during rush hours.[43]

The West Side Branch was extended northward to a temporary terminus of 221st Street and Broadway on March 12, 1906.[24]: 191 [44] This extension was served by shuttle trains operating between 157th Street and 221st Street.[45] On April 14, 1906, the shuttle trains started stopping at 168th Street. On May 30, 1906, the 181st Street station opened, and the shuttle operation ended.[46]: 71, 73 Through service began north of 157th Street, with express trains terminating at 168th Street or 221st Street.[46]: 175–176 The original system as included in Contract 1 was completed on January 14, 1907, when trains started running across the Harlem Ship Canal on the Broadway Bridge to 225th Street,[44] meaning that 221st Street could be closed.[24]: 191 Once the line was extended to 225th Street, the structure of the 221st Street station was dismantled and was moved to 230th Street for a new temporary terminus. Service was extended to the temporary terminus at 230th Street on January 27, 1907.[24]: 191 The 207th Street station was completed, but did not open until April 1, 1907, because the bridge over the Harlem River was not yet completed.[40]

The original plan for the West Side Branch had called for it to turn east on 230th Street, running to the New York Central Railroad's Kings Bridge station at a point just west of Bailey Avenue.[47] An extension of Contract 1, officially Route 14, north to 242nd Street at Van Cortlandt Park was approved on November 1, 1906.[17]: 204 This change also called for the abandonment of the route along 230th Street.[24]: 191 This extension opened on August 1, 1908.[24]: 191 [48] When the line was extended to 242nd Street the temporary platforms at 230th Street were dismantled, and were rumored to be brought to 242nd Street to serve as the station's side platforms. There were two stations on the line that opened later; 191st Street and 207th Street. The 191st Street station did not open until January 14, 1911, because the elevators and other work had not yet been completed.[40]

To complete Contract 2, the subway had to be extended under the East River to reach Brooklyn. The tunnel was named the Joralemon Street Tunnel, which was the first underwater subway tunnel connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn, and it opened on January 9, 1908, extending the subway from Bowling Green to Borough Hall.[49] On May 1, 1908, the construction of Contract 2 was completed when the line was extended from Borough Hall to Atlantic Avenue near the Flatbush Avenue LIRR station.[50] With the opening of the IRT to Brooklyn, ridership fell off on the BRT's elevated and trolley lines over the Brooklyn Bridge as Brooklyn riders chose to use the new subway.[51]

Proposed expansion

[edit]In 1903, the New York Rapid Transit Board ordered Chief Engineer Parsons to create a plan for a comprehensive subway system to serve all of New York City. Parsons presented his plan to the Board on February 19, 1904, for his proposals in Manhattan and the Bronx, and released his proposals for Brooklyn and Queens on March 12.[4]

Modifications

[edit]On June 27, 1907, a modification called the 96th Street Improvement was made to Contract 1, which would add tracks at 96th Street in order to remove the at-grade junction north of the 96th Street station. Here, trains from Lenox Avenue and Broadway would switch to get to the express or local tracks and would delay service.[52] The tracks would have been constructed with the necessary fly-under tracks and switches.[25]: 14 The work was partially completed in 1908, but was stopped because the introduction of speed-control signals made the remainder of the project unnecessary. Provisions were left to allow the work to be completed later on. The signals were put into place at 96th Street on April 23, 1909. The new signals allowed trains approaching a station to run more closely to the stopped train, eliminating the need to be separated by hundreds of feet. The new signals were also installed at Grand Central, 14th Street, Brooklyn Bridge, and 72nd Street by November 1909, allowing the IRT to run two or three more trains during peak hours.[24]: 85–87, 191 [53]: 166–167

On June 18, 1908, a modification to Contract 2 was made to add shuttle service between Bowling Green and South Ferry. At the time, of the trains that continued south of City Hall, some trains ran through to Brooklyn, with the rest running to South Ferry before returning to uptown service. It was determined that the operation of trains via the South Ferry Loop impeded service to Brooklyn, prohibiting a doubling of Brooklyn service. In order to increase Brooklyn service, it was decided to continue serving South Ferry via shuttle service. An additional island platform and track were constructed on the west side of the Bowling Green station to allow for the shuttle's operation. The cost was estimated to be $100,000. While the change inconvenienced South Ferry riders, it stood to benefit the greater number of Brooklyn riders.[54] Though work on the project was not fully completed, shuttle service began on February 23, 1909, allowing all Broadway express trains to run to Brooklyn, instead of having some of them terminate at South Ferry, increasing express service to Brooklyn by about 100 percent.[55][56]

On August 9, 1909, a modification to Contract 1 was made, allowing for the construction of an infill station on the West Farms Branch at Intervale Avenue. The station would have an escalator to the mezzanine, where the ticket office would be located.[56] Construction of the station began in December 1909. The station opened on April 30, 1910, even though work on the station was not completed until July. In February 1910, work began on the construction of a permanent terminal for the West Farms Branch at Zoological Park at 181st Street and Boston Road, replacing the temporary station at this location. The new station cost $30,000[24]: 10 and opened on October 28, 1910.[57]: 105–106

To address overcrowding, the New York State Public Service Commission proposed to lengthen platforms to accommodate ten-car express and six-car local trains.[53]: 168 On January 18, 1910, a modification was made to Contracts 1 and 2 to lengthen station platforms to increase the length of express trains to eight cars from six cars, and to lengthen local trains from five cars to six cars. In addition to $1.5 million spent on platform lengthening, $500,000 was spent on building additional entrances and exits. It was anticipated that these improvements would increase capacity by 25 percent.[57]: 15 In September 1910, it was estimated that work to lengthen express platforms to fit ten-car trains would be sufficiently complete to allow for ten-car expresses by February 1, 1911, and that work to lengthen local platforms to fit six-car trains would be sufficiently complete to allow for six-car locals by November 1, 1910.[58] On January 23, 1911, ten-car express trains began running on the Lenox Avenue Line, and on the following day, ten-car express trains were inaugurated on the Broadway Line. The platforms at all but three express stations were extended to accommodate ten-car trains. The platforms at 168th Street and 181st Street, and the northbound platform at Grand Central, were not extended. Until the platform extensions were completed, the first two cars of trains overshot the platform, and the doors did not open in these cars. All southbound stations on the Broadway Line north of 96th Street and on the White Plains Road Line north of 149th Street, as well as at Mott Avenue, Hoyt Street, and Nevins Street, were only eight cars long.[53]: 168 [59]

Service pattern

[edit]Initially, express service ran every two minutes, running at an average speed of 30 miles per hour (48 km/h), with service alternating between the east and west branches. Express trains were eight cars long, with three trailer cars, and five motor cars. Local trains ran at an average speed of 16 miles per hour (26 km/h), and also alternated between the east and west branches. Service was provided with five-car trains, of which two cars were trailers, and three were motors.[4]

Express trains began at South Ferry in Manhattan or Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, while local trains typically began at South Ferry or City Hall, both in Manhattan. Local trains to the West Side Branch (242nd Street) ran from City Hall during rush hours and continued south at other times. East Side local trains ran from City Hall to Lenox Avenue (145th Street). All three branches were initially served by express trains; no local trains used the East Side Branch to West Farms (180th Street).[60]

Beginning on June 18, 1906, Lenox Avenue express trains no longer ran to 145th Street; all Lenox Avenue express trains ran to the West Farms Line.[46]: 78 When the Brooklyn branch opened, all West Farms express trains and rush-hour Broadway express trains operated through to Brooklyn.[61] Essentially each branch had a local and an express, with express service to Broadway (242nd Street) and West Farms, and local service to Broadway and Lenox Avenue (145th Street).[62] In November 1906, some southbound express trains on the West Side branch began skipping the four stations between 137th and 96th Streets during rush hours;[63] however, Upper Manhattan residents reported that these express services did not save time and operated inconsistently.[64]

When the "H" system opened in 1918, all trains from the old system were sent south from Times Square–42nd Street along the new IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. Local trains (Broadway and Lenox Avenue) were sent to South Ferry, while express trains (Broadway and West Farms) used the new Clark Street Tunnel to Brooklyn.[65] These services became 1 (Broadway express and local), 2 (West Farms express), and 3 (Lenox Avenue local) in 1948. The only major change to these patterns was made in 1959, when all 1 trains became local and all 2 and 3 trains became express.[66][67][68] The portion south of Grand Central–42nd Street became part of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, and now carries 4 (express), 5 (express), 6 (local), and <6> (local) trains; the short piece under 42nd Street is now the 42nd Street Shuttle.[65]

Design

[edit]Underground stations

[edit]Platform layouts

[edit]

The designs of the underground stations are inspired by those of the Paris Métro,[18]: 5 whose design had impressed Parsons.[19]: 46–47 With few exceptions, Parsons's team designed two types of stations for Contracts 1 and 2. Local stations, which serve only local trains, have side platforms on the outside of the tracks.[18]: 4 [69]: 8 Local stations were spaced .25 miles (0.40 km) apart on average.[4][70]: 3 Express stations, which serve both local and express trains, have island platforms between each direction's pair of local and express tracks. There were five express stations: Brooklyn Bridge, 14th Street, Grand Central, 72nd Street, and 96th Street,[18]: 4 [69]: 8 which were spaced 1.5 miles (2.4 km) apart on average.[4][70][71]: 3 The Brooklyn Bridge, 14th Street, and 96th Street stations also had shorter side platforms for local trains, though these platforms have since been abandoned at all three stations.[69]: 8 [72]: 4 There was not enough space for side platforms at the Grand Central and 72nd Street stations.[71]: 3 Stations north of 96th Street and south of Brooklyn Bridge, which served both local and express trains, typically had two side platforms and two or three tracks.[18]: 4 [69]: 8

Some exceptions were made to the standard platform design. The now-closed City Hall station contains one balloon loop and was designed in a much more ornate style than all of the other stations.[18]: 4–5 [69]: 8 The City Hall station originally only served passengers entering the system; passengers had to disembark at the Brooklyn Bridge station.[71]: 4 The Bowling Green station, opened as part of Contract 2, was built with one island platform and two tracks, although a third track and a second island platform was built in 1908 for the Bowling Green–South Ferry shuttle.[73] The South Ferry loops, also part of Contract 2, had two balloon loops with a platform on the outer loop.[74] The Central Park North–110th Street station, north of 96th Street, had a single island platform.[72]: 4 Other nonstandard platform layouts included a Spanish solution (two side platforms, one island platform, and two tracks), used at the terminal stations at Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street[75] and 180th Street–Bronx Park.[76]

Generally, local platforms south of 96th Street were originally 200 feet (61 m) long and between 10 and 20 feet (3.0 and 6.1 m) wide. Express platforms, all platforms north of 96th Street, and all Contract 2 platforms were originally 350 feet (110 m) long and between 15.5 and 30 feet (4.7 and 9.1 m) wide.[18]: 4–5 [69]: 8 The 200-foot local platforms could fit five cars of the IRT's original rolling stock, while the 350-foot platforms could fit eight original cars.[71]: 2 [77] Both the local and express trains were slightly longer than the platforms, as each car was about 51 feet (16 m) long; thus, the frontmost and rearmost doors of each train did not open.[77]

Passenger circulation and structural features

[edit]One major consideration was the avoidance of escalators and elevators as the primary means of access to the station. Many of the local stations are just below ground level and have a fare control (turnstile) area at the same level as the platform.[69]: 8 [18]: 4 The local stations are generally 17 feet (5.2 m) under the street. Platform-level control areas generally measured 30 by 45 feet (9.1 by 13.7 m) and contained an oak ticket booth and two restrooms.[69]: 8–9 Every station, apart from City Hall, had a restroom.[72]: 5 Local stations from Worth Street to 50th Street were designed symmetrically on either side of their respective cross street. To provide space for the ticket offices and waiting rooms, an area of the cross street was excavated. At platform level, separate entrances and exits were installed on either end of each platform, and short wide stairways were installed on each platform. The entrance stairway for each platform was placed at the back of the waiting room, while the exit stairway was at the back of the platform directly to the street. North of 59th Street, Broadway is wide enough that stations' platforms generally did not extend under the sidewalk; at these stations, access to the platforms was provided by a single wide staircase. Most stations in which the tracks were not under the middle of the street, with only a single platform under the sidewalks, were supplied with a pair of wide staircases due to their location in Harlem's business district.[4]

Among stations with two side platforms, the Times Square and Astor Place stations had underpasses connecting the platforms, while the 103rd Street, 116th Street, 168th Street, 181st Street, and Mott Avenue stations had overpasses linking the platforms.[71]: 2–3 [6]: 146 Crossovers and crossunders were not provided at other stations,[6]: 146 although underpasses were installed at 28th Street and 66th Street after the original IRT opened.[71]: 3 A slight modification to the standard local station design was also done at 116th Street–Columbia University,[4] which was designed with a station house in the median of Broadway. The ticket office for the station was at street level. A stairway led from the station house to an overpass over the tracks, which provided access to both platforms.[6]: 146

Access to express stations was provided by overpasses, underpasses, and stairways directly leading to the street.[4] The Brooklyn Bridge, 14th Street, and Grand Central stations were 25 feet (7.6 m) below street level;[69]: 8–9 all three stations had mezzanines above the platform.[69]: 8–9 [71]: 2–3 The 72nd Street station was only 14 feet (4.3 m) beneath the street, since its entrance was through a control house directly above the platform, while the 96th Street station had an underpass because a large trunk sewer made a mezzanine impractical.[69]: 8–9

Three stations, 168th Street, 181st Street, and Mott Avenue, were built at a deep level and contain arched ceilings; they were only reachable by elevators.[69]: 8 [78][a] The 191st Street station was also built at a deep level, but contains a passageway in addition to its elevator entrance.[80] Deep stations had their ticket offices directly under the sidewalk, and had a stairway and elevators that could accommodate 3,500 riders per hour leading down to the station. These stations were constructed with large arches extending over the tracks and platforms. The elevators led down to an overpass crossing the tracks to provide access to both platforms.[4] The 168th Street, 181st Street, 191st Street, and Mott Avenue stations contained double-deck elevators, all of which have since been removed or replaced. The lower deck carried passengers from the platform to the mezzanine, while the upper deck carried passengers from a mezzanine to an overpass above the platforms.[71]: 3

In the majority of underground stations, excluding the deep-level stations, the roofs of the platforms are supported by round cast iron columns placed every 15 feet (4.6 m). Additional columns between the tracks, placed every 5 feet (1.5 m), support the jack-arched concrete station roofs. Each platform consists of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which are drainage basins.[18]: 5 [69]: 9 Bronze ventilation grates were placed in the lowest portions of the station walls, as well as in the cornices. At twenty stations where the platforms were beneath the sidewalk, overhead vault lights were installed to provide light to stations; incandescent bulbs provided artificial lighting. The ceilings were finished in plaster, applied to wire lath.[69]: 9–11 [72]: 5 The walls of the station were built with brick, and were covered by plaster ceilings and enameled tiles.[4] The City Hall station, the only one whose decorative treatment was explicitly part of its structure, contains vaulted ceilings with Guastavino tile.[18]: 6 [69]: 14–15

Decorations

[edit]

Heins & LaFarge were commissioned to design the stations' decorations;[71]: 2 while some of these original designs remain intact, others have been modified or removed over the years.[18]: 3, 5 At stations with side platforms, wainscoting and wall surfaces are generally given a similar treatment. The lowermost 2.5 feet (0.8 m) of the walls are wainscoted in either Roman brick or marble to resist heavy wear.[4] The rest of the walls are made of white glass or glazed tiles measuring 3 by 6 inches (76 mm × 152 mm). The walls are generally divided at 15-foot (4.6 m) intervals by colorful tile or mosaic pilasters.[18]: 5 [69]: 10 [81]: 67 Architectural critic Christopher Gray wrote that "the stations were meant not only to appear sanitary and healthful but also to constitute a major public work like the automobile parkways of the 1920s".[82]

Under the IRT's contract with the city, the company was theoretically allowed to place advertisements on the blank walls between the pilasters.[83]: 46, 48 Belmont had tried to pare down the stations' decorations in 1902 so he could increase his advertising revenue, although this did not become widely known until late 1904.[82] In practice, the Rapid Transit Commission had banned the IRT from displaying advertisements or adding objects such as slot machines to stations.[84] The public initially opposed advertisements in stations.[83]: 46, 48 [82] The Real Estate Record and Guide wrote that the advertisements "irretrievably mar the appearance of a very appropriate and admirable piece of interior decoration",[85] while the New-York Tribune said "it was a scandal to have the stations of a road owned by the city used in such vulgar and offensive fashion for advertising purposes".[86] Legal disputes over the advertisements continued until 1907, when a New York Supreme Court judge ruled that the IRT could display advertising at stations.[82]

Decorative details in each station varied considerably to give each station a distinct identity, to improve the appearance of the stations, and to make it easier for passengers to recognize a station through the windows of a subway car.[4] There are friezes atop each station's walls, which are generally interspersed with plaques signifying the street name or number, as well as plaques with a symbol that is associated with a local landmark or another object of local significance.[18]: 5 [69]: 10 Such plaques may have been installed to provide a visual aid to the large immigrant populations who were expected to ride the subway, many of whom did not read English,[83]: 46 [87]: 5347 although a writer for The New York Times said in 1957 that "non-English readers would have had to be rich in associative powers".[88] Heins & LaFarge worked with the ceramic-producing firms Grueby Faience Company of Boston and Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati to create the ceramic plaques.[89][90] Mosaic tablets with the name of the station are put at regular intervals within the stations' walls.[18]: 5 The bright colors were intended to catch the attention of the casual observer,[69]: 11 [91][92] and each station used a different color scheme.[92] Other architectural details were made of glazed terracotta or, in more important stations, of faience. These materials were of high quality but were also expensive, requiring Heins & LaFarge to limit their use of such materials in the IRT stations.[69]: 11

Entrances and exits

[edit]Heins & LaFarge also designed entrance and exit structures for the underground stations.[18]: 3 At stations with platform-level fare control areas, there were generally four staircases to the street, two each for entrance and exit.[69]: 8 A station could have between two and eight staircases in total.[72]: 5 At some stations, such as the 23rd Street station, the IRT made agreements with property owners to construct entrances into adjacent buildings.[83]: 48 [69]: 8 As part of Contract 2, an underground passageway was constructed to connect a large building with the Wall Street station.[4]

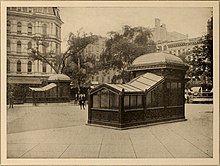

Most stations had entrance and exit kiosks, extremely ornate structures made of cast iron and glass, being inspired by those on the Budapest Metro, which themselves were inspired by ornate summer houses called "kushks".[83]: 443 [81]: 66–67 One hundred and thirty-three kiosks of varying width were made by Brooklyn-based manufacturer Hecla Iron Works. Exit kiosks were distinguished by their four-sided pyramidal wire-glass skylights, while entrance kiosks had domed roofs with cast-iron shingles. The kiosks also carried ventilation shafts for the stations' restrooms, which were generally directly underneath each kiosk.[69]: 13 The entrance and exit kiosks were considered obstructions to traffic, and were frequently vandalized and used as advertising boards. As a result, they were all removed by the late 20th century.[69]: 13 [81]: 67 One replica of an entrance kiosk exists at the Astor Place station.[93]

The 72nd Street, 103rd Street, 116th Street–Columbia University, and Mott Avenue stations were accessed via large brick control houses; those at 103rd and 116th Streets no longer exist.[69]: 8 [83]: 46 [94]: 2 At these stations, the ticket booths and restrooms were in the surface-level control houses rather than inside the station.[72]: 5 Control houses of a similar style were also built at Bowling Green and Atlantic Avenue.[83]: 46 [94]: 2 They were probably inspired by those on the Boston subway and, rather than using a specific historical style, were generally fanciful in design. The control houses were decorated with bricks, limestone, and terracotta, and contained details similar to the buildings at the Bronx Zoo's Astor Court, also designed by Heins & LaFarge.[69]: 11–13

Tunnels

[edit]McDonald's contract with the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners specified the methods of construction to be used for the subway. The board preferred a shallow tunnel as used on the Boston subway and on the Budapest Metro's Line 1. Cut-and-cover construction was permitted, although open excavations were not to exceed 400 feet (120 m) unless there were overpasses for pedestrian and vehicle traffic. Open excavation was permitted between City Hall and 34th Street; along 42nd Street; and along Broadway from 42nd to 60th Streets. Open excavation was prohibited between 34th and 40th Streets due to the presence of the Murray Hill Tunnel, as well as on the Lenox Avenue Line from 104th to 110th Streets, which ran under the North Woods of Central Park. North of 60th Street the contractor could choose "the most expeditious manner possible, having due regard to safety of persons and property and reasonable consideration for the accommodation of street traffic."[23]: 235–236 The tunnels had a minimum railway curve radius of 147 feet (45 m), at the City Hall station, and a maximum gradient of 3 percent, in the Harlem River tunnels.[71]: 2

For the most part, cut-and-cover construction was used. Cut-and-cover tunnels contain concrete foundations, and have steel beams supporting the ceiling arches, as in the stations.[71]: 2 [72]: 6 [23]: 237 Cut-and-cover tunnels are typically shallow, as the roofs of the tunnels are usually only 30 inches (760 mm) beneath the surface; this provided room for the underground conduits that were used by streetcars in New York City at the time. Each trackway measured about 12 feet 4 inches (3.76 m) from the center of the column to the outer wall of each tunnel, and 12 feet 6 inches (3.81 m) from the top of the rail to the top of the ceiling. A four-track tunnel typically measured 50 feet (15 m) wide; the outer walls of the tunnels did not have duct benches.[71]: 2 Flat-roof tunnels were used for short sections of the route, and about 4.6 miles (7.4 km) of concrete-lined tunnels were also built.[72]: 6 In the Brooklyn extension to Atlantic Avenue, the concrete floor is designed as a thick slab of unreinforced concrete (as in the Manhattan tunnels), but the walls and roof are primarily constructed of reinforced concrete and lack steel columns.[23]: 262–263

The city's topology and preexisting infrastructure precluded the use of the cut-and-cover construction method in parts of the original line. Concrete-lined tunnels were built in Murray Hill and under Central Park.[23]: 236, 256–257 In Murray Hill, the four-track line was divided into two double-track tunnels, providing space between the express tracks for a spur leading directly to the mainline railroad station at Grand Central Terminal. This spur was never built, and the space was instead used to extend the IRT Lexington Avenue Line's express tracks northward as part of the Dual Contracts.[71]: 7–8 On the West Side Line between 151st and 155th Streets, and between 158th Street and Fort George, a deep bore tunnel was used to cut through high, rocky hills.[23]: 236, 256–257 The Joralemon Street Tunnel under the East River, between the Bowling Green and Borough Hall stations, was dug as a pair of cast iron tubes.[23]: 261–262 [95]

Elevated segments

[edit]The topology of Manhattan and the Bronx also necessitated the construction of elevated viaducts, particularly on the West Side Line between 122nd and 135th Streets; on the West Side Line north of Fort George in Manhattan and the northwest Bronx; and on the East Side Line east of Melrose Avenue in the central Bronx.[23]: 236 Steel viaducts with open floors were used because they were generally cheaper than viaducts with solid floors, which were used in places such as Philadelphia.[71]: 2 On the original IRT elevated viaducts, the elevated structure is carried on pairs of bents, one on each side of the road, at locations where the rails are at most 29 feet (8.8 m) above the ground. There is zigzag lateral bracing at intervals of every four panels. Higher viaducts are carried on sets of four towers: those on opposite sides of the road (situated transversely) are 29 feet (8.8 m) apart from each other, while those on the same side (situated longitudinally) are 20 to 25 feet (6.1 to 7.6 m) apart. The tops of the towers have X-bracing, and the connecting spans have two panels of intermediate vertical sway bracing between the three pairs of longitudinal girders.[72]: 7 [96]: 60–61 [97]

Elevated stations were designed by Heins & LaFarge in a similar design to those on the existing elevated railway system. Contracts 1 and 2 only provided for local and terminal elevated stations. Generally, each elevated platform contains a Victorian style station house at platform level, with wood siding and a copper hip roof. The stairways from each station house to the street are decorated with elaborate iron work and are also covered by canopies. The platforms also contain canopies extending for a short distance in either direction from the station house, while the remaining sections of the platforms only contain iron guard rails interspersed with lampposts.[69]: 13–14 Elevated stations on a viaduct had their ticket offices and waiting rooms at street level, with access to the platforms provided by elevators or stairways.[4]

Two of the original IRT's elevated stations differ significantly in design from the others. The 125th Street station on the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line was carried on a steel-arch viaduct high across the street, with a smaller station house below the tracks, while the Dyckman Street station sat on a masonry embankment with a control area beneath the platforms.[69]: 13–14 Escalators were added at the 125th Street station on the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, as well as at the 177th Street station.[71]: 3

Tracks

[edit]The tracks themselves were made of 100-pound (45 kg) rails, which rested on wooden cross ties and were placed on ballasted trackbeds. Originally, the system was supposed to have used 80-pound (36 kg) rails, which would have been secured to longitudinal wooden ties embedded within concrete trackbeds. A 0.25-mile (0.40 km) section of track, consisting of 80-pound rails with longitudinal ties, was installed on the Long Island Rail Road near the Jamaica station, but this was found to be less effective than 100-pound rails with cross ties.[71]: 2

Equipment and mechanical features

[edit]Electrification

[edit]

The main powerhouse was the IRT Powerhouse, occupying an entire block bounded by 58th Street, 59th Street, 11th Avenue, and 12th Avenue. The structure was designed by a group of IRT engineers led by Paul C. Hunter, with a freestanding facade designed by Stanford White. It had an operating room on the north side and a boiler room on the south side.[69]: 15–16 [98] The powerhouse also served as an aboveground focal point for the IRT system, similar to Grand Central Terminal or St Pancras railway station, because the City Hall station was relatively small and not readily visible except from underground.[69]: 15 The building became unnecessary to the subway system in the 1950s, and since then, Consolidated Edison has used the space to supply the New York City steam system.[99]

Eight power substations were also erected, and were designed by Hunter with the assistance of IRT engineers; six of the substations were identical in design.[69]: 17 Most substations were up to half a block from the subway, but substations 17 and 18 are next to the subway itself, as they were built in neighborhoods that were sparsely populated at the time of the IRT's opening.[100]: 329 From the main powerhouse, 11,000 volts of alternating current passed through high tension feeder cables that ran under 58th Street eastward to the subway tunnel under Broadway, and were then carried through ducts to the substations. The ducts ran alongside the tunnels and underneath the platforms to the powerhouse.[100]: 330 The substations converted the alternating current to 600 volts of direct current for use by the trains.[100]: 330, 332

Power for the original IRT subway was provided to the trains via a 600-volt direct current third rail system.[100]: 341 [87]: 5347 Alternating current traction was comparatively unsuccessful at the IRT's opening, and existing elevated lines operated by the Manhattan Railway Company, which the IRT hoped to acquire, had also been electrified with third rail between 1899 and 1900.[100]: 341 The third rail runs along each of the two running rails. Electrical engineer Lewis B. Stillwell designed a wooden plank that was hung slightly above the third rail to prevent debris from falling onto it. Power to each track section was generally supplied by the nearest substation.[100]: 342 Rolling stock would collect current from the third rail via over-running contact shoes that glided over the top surface of the third rail.[100]: 344

Rolling stock

[edit]

John B. McDonald, the contractor in charge of building the first IRT subway, was also given specifications for the system's rolling stock, or trains. There were to be enough rolling stock for a three-car local train to arrive every two minutes and a four-car express train every five minutes on the trunk lines. The cars had to allow easy passenger boarding and alighting, be attractive in appearance, seat at least 48 persons, and contain thorough ventilation.[100]: 341

The first rolling stock ordered for the IRT was the 500-car Composite, which arrived from 1903 to 1904, and manufactured by the Jewett, St. Louis, Wason, and John Stephenson companies. This count excluded two prototype cars. The Composites were so named because they were made of a wood and steel composite.[100]: 346–347 [101]: 56–58 In 1904, an order was placed with American Car and Foundry (ACF) for 300 Gibbs Hi-V cars, the first production all-steel passenger cars in the world. These were named after their designer, George Gibbs.[101]: 59 [102]: 27 Transit officials were initially reluctant to use the Composite and steel cars in the same train set because of the risk that could be posed if the mixed trains were involved in a crash.[101]: 59 The IRT decided to order only steel cars after a collision between a Composite and steel train in 1906, which led to both cars burning; the steel train was mostly intact but the Composites were almost completely destroyed.[100]: 348 The Composite fleet was ultimately transferred to the elevated lines with the arrival of additional steel subway cars.[100]: 348 [101]: 59 ACF built fifty steel Deck Roof Hi-V cars for the IRT in 1907 and 1908.[101]

The original subway cars, designed with two doors at the ends of each side, were inefficient, causing delays of up to fifty seconds during rush hours. In response, the Public Service Commission started to order cars with two end doors and a center pair of doors on each side, and converted existing rolling stock to accommodate center doors. The first center-door fleet, the Hedley Hi-V, was ordered in 1909 and started to arrive the next year.[53]: 167–168

Impact

[edit]Ridership

[edit]The IRT was instantly popular upon its opening, with the New-York Tribune proclaiming the "birth of [the] subway crush".[53]: 146 However, within a week of its opening, the first subway line became overburdened by the sheer number of passengers using it.[83]: 46 The first line, designed to accommodate up to 600,000 passengers a day, was already accommodating half that amount by December 1904 and was nearing its capacity by the first anniversary of its opening. With subsequent expansions, the IRT's average daily traffic increased to 800,000 by 1908, and to 1.2 million by 1914. Consulting engineer Bion J. Arnold wrote in 1908 that "the number of patrons is increasing yearly and the maximum carrying capacity is therefore taxed to the utmost limit".[53]: 146–147 Express services were more popular than IRT planners had expected. At 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), the express trains were the fastest form of urban transportation in the city when they were not delayed, but they were frequently delayed because many passengers wished to transfer to and from local services.[53]: 151

The city could only afford one subway line in 1900 and had hoped that the IRT would serve mainly to relieve overcrowding on the existing transit system. However, crowds on existing transportation modes did not decrease significantly: elevated ridership in 1907 was one percent less than in 1904, while streetcar ridership declined four percent from 1904 to 1910.[53]: 146–147 A report in 1906, published by the New York State Railroad Commission, stated that Greater New York's growth was exceeding the development of its rapid transit.[103] In general, this could be attributed to huge growth in the years just prior to the subway's opening, with elevated ridership having increased by fifty percent from 1901 to 1904.[53]: 148 Between 1904 and 1914, the total number of passengers in New York City increased by more than 60 percent to 1.753 billion.[53]: 153 The technical modifications made in the late 1900s and early 1910s, including signaling system upgrades and platform extension, allowed the IRT to run a train on the express and local tracks once every 108 seconds, or 33 trains per hour.[53]: 168

City development

[edit]South of 42nd Street, the opening of the subway had little impact on retail. While high-end retailers and middle-class department stores were moving northward at the beginning of the 20th century, they chose to remain further west on Sixth and Fifth Avenues.[53]: 182 Union Square, and Fourth Avenue between 14th and 25th Streets (now Park Avenue South), was becoming a major wholesaling district with several loft and office buildings by 1909.[104][105] The subway had a more visible impact north of 42nd Street, where it switched from Manhattan's east side to its west side. Just north of 42nd Street and Broadway was Longacre Square, which saw an increase in development after the IRT subway was announced, including the new headquarters of The New York Times.[53]: 182 Longacre Square was renamed Times Square in 1904, after the Times, in part because the IRT subway station there necessitated a unique station name.[106] The subway's opening prompted the relocation of Manhattan's theater district to the stretch of Broadway surrounding Times Square.[53]: 183–184

In the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the opening of the subway resulted in residential development along Broadway, which in the late 19th century was unevenly developed with low-rise buildings. The presence of Central Park had previously limited the extent of development in the Upper West Side, since not many people from the more densely developed Upper East Side were willing to cross the park. The subway's opening brought about an increase in land values around it, as apartment buildings of over 10 stories and smaller business structures were erected on Broadway.[53]: 185–186 Further north, around the West Side Branch in Morningside Heights, developers started constructing middle-class apartment buildings when the subway opened.[107] Around the East Side Branch in central Harlem, commercial developments such as theaters and banks moved to Lenox Avenue, under which the subway ran.[53]: 190

When the IRT subway opened, the Bronx and the northern end of Manhattan were largely rural. Real estate speculators quickly bought up tracts around subway stations, subdivided the land into smaller lots, and sold these lots to small-scale builders. Tenement housing was the most prevalent type of development in these neighborhoods, as they were cheap to construct and many speculators intended to sell their land for profit. The tenements were almost exclusively developed within two blocks of the subway and were largely concentrated north of 130th Street.[53]: 195–196 The construction of tenement housing in these neighborhoods allowed greater mobility for lower-class residents of the Lower East Side and other neighborhoods. From 1900 to 1920, the population of Upper Manhattan and the Bronx increased at a greater rate than in the rest of the city. The development of tenements caused a change in reformers' views of the subway, and zoning regulations such as the 1916 Zoning Resolution were enacted to regulate haphazard development, such as that caused by the construction of subway lines.[53]: 200–201

After the Dual Contracts

[edit]

The Dual Contracts, signed in 1913, called for the splitting of the original Manhattan trunk line into an East Side Line under Lexington Avenue and a West Side Line under Broadway and Seventh Avenue.[108] The first portion of the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line south of Times Square–42nd Street opened on June 3, 1917, and was extended to South Ferry on July 1, 1918.[109] The new portion of the Lexington Avenue Line from Grand Central to 125th Street opened on July 17, 1918.[110] The new "H" system was implemented on August 1, 1918, joining the two halves of the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, and the two halves of the Lexington Avenue Line.[111] The portion of the original trunk line between Times Square and Grand Central was turned into the 42nd Street Shuttle. The completion of the "H" system doubled the capacity of the IRT system.[112] The IRT was also extended to Queens through the construction of the Flushing Line, the first part of which would open in 1915.[113]

By the 1950s and 1960s, almost all of the original IRT stations had been lengthened to fit ten 51.4-foot (15.7 m) cars.[114][115][b] Several stations were closed during this time. The first of these was City Hall, once the architectural showpiece of the system, which shuttered in 1945 after it was deemed too expensive to modernize.[118] 18th Street closed three years later because it was near the 14th Street station.[119] The 180th Street–Bronx Park terminal was closed and demolished in 1952 as a result of a program to improve service on the White Plains Road Line.[120] 91st Street shuttered in 1959 after platforms at the 86th Street and 96th Street stations were lengthened,[115] and Worth Street was closed in 1962 after platforms at the Brooklyn Bridge station were lengthened.[121] The original South Ferry loop station remained operational until 2009, when it was replaced by a new station on the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line.[122][c]

Although many design elements on the original IRT have been removed or modified over the years,[123] some parts of the system have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) or designated as New York City designated landmarks (NYCL).[124][125] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the interiors of twelve original IRT stations as New York City landmarks in 1979.[18][126] The LPC has also protected other parts of the original IRT, including control houses at Bowling Green[127] and 72nd Street.[128] In addition, the MTA nominated many of these structures for NRHP status in 1999.[123]

Station listing

[edit]| Station | Structure | Tracks[d] | Opened | Notes[e] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Branch | ||||

| Atlantic Avenue | Underground | 2 | May 1, 1908[50] | Station and original control house on NRHP[124] |

| Nevins Street | Underground | 2 | May 1, 1908[50] | |

| Hoyt Street | Underground | 2 | May 1, 1908[50] | |

| Borough Hall | Underground | 2 | January 9, 1908[41][49] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| South Ferry | Underground | 1 (loop) | July 10, 1905[41] | Closed March 16, 2009[c] |

| Bowling Green | Underground | 2 | July 10, 1905[41] | Original control house on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Wall Street | Underground | 2 | June 12, 1905[131] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Fulton Street | Underground | 2 | January 16, 1905[132] | Original portions of station listed as NYCL[125] |

| City Hall | Underground | 1 (loop) | October 27, 1904[133] | Closed December 31, 1945.[118] Station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Brooklyn Bridge | Underground | 4 (all) | October 27, 1904[133] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| Worth Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Closed September 1, 1962[121] |

| Canal Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| Spring Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| Bleecker Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Astor Place | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 14th Street–Union Square | Underground | 4 (all) | October 27, 1904[133] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 18th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Closed November 8, 1948[119] |

| 23rd Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 28th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 33rd Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Grand Central–42nd Street | Underground | 4 (all) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| Times Square | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 50th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 59th Street–Columbus Circle | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 66th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 72nd Street | Underground | 4 (all) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station and control house on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 79th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 86th Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 91st Street | Underground | 4 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Closed February 2, 1959[115] |

| 96th Street | Underground | 4 (all) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| West Side Branch (splits at 96th Street) | ||||

| 103rd Street | Underground | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 110th Street | Underground | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 116th Street | Underground | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Original portions of station on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| Manhattan Street | Elevated (steel arch) | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | Viaduct on NRHP and NYCL[124][125] |

| 137th Street | Underground | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 145th Street | Underground | 3 (local) | October 27, 1904[133] | |

| 157th Street | Underground | 2 | November 12, 1904[134] | |

| 168th Street | Underground (deep level) | 2 | April 14, 1906[135] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 181st Street | Underground (deep level) | 2 | May 30, 1906[136][40] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 191st Street | Underground (deep level) | 2 | January 14, 1911[137] | |

| Dyckman Street | Elevated (masonry) | 2 | March 12, 1906[138] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| 207th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | April 1, 1907[40] | |

| 215th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | March 12, 1906[138] | |

| 221st Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | March 12, 1906[138] | Closed January 14, 1907[40] |

| 225th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | January 14, 1907[44] | |

| 231st Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | January 27, 1907[40] | |

| 238th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | August 1, 1908[139] | |

| Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street | Elevated | 2 | August 1, 1908[139] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| West Side Branch to Lenox Avenue (splits at 96th Street) | ||||

| 110th Street | Underground | 2 | November 23, 1904[140] | |

| 116th Street | Underground | 2 | November 23, 1904[140] | |

| 125th Street | Underground | 2 | November 23, 1904[140] | |

| 135th Street | Underground | 2 | November 23, 1904[140] | |

| 145th Street | Underground | 2 | November 23, 1904[140] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| West Side Branch to West Farms (splits from branch to Lenox Avenue at 142nd Street Junction) | ||||

| Mott Avenue | Underground (deep level) | 2 | July 10, 1905[41] | Original control house on NRHP[124] |

| 149th Street | Underground | 2 | July 10, 1905[41] | |

| Jackson Avenue | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| Prospect Avenue | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | Station on NRHP[124] |

| Intervale Avenue | Elevated | 3 (local) | April 30, 1910[57] | |

| Simpson Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | |

| Freeman Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | |

| 174th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | |

| 177th Street | Elevated | 3 (local) | November 26, 1904[41] | |

| 180th Street | Elevated | 2 | November 26, 1904[41] | Closed August 4, 1952; only part of the original subway to be completely demolished[120] |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The elevators at Mott Avenue were removed in 1975.[79]

- ^ As of 2019[update], three stations from Contracts 1 and 2 remain operational but cannot fit ten 51-foot-long cars. The platforms at 145th Street and Lenox Avenue are 348 feet (106 m) long and can fit six-and-a-half 51-foot IRT subway cars.[116] The Times Square and Grand Central stations, now part of the 42nd Street Shuttle, were extended in 2021 to fit six 51-foot cars.[117]

- ^ a b The original portions of station was the outer of two loops, which became part of the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line in 1918. It was closed on March 16, 2009,[122] but was returned to service from April 4, 2013, to June 26, 2017, while its replacement was being repaired.[129] An inner loop, not part of the original IRT subway, was in service from 1918 to 1977.[130]

- ^ The number of tracks in the station prior to the implementation of the "H" system in 1918. Stations marked "Local" could only be served by local trains on the outermost tracks. Stations marked "All", with 3 or 4 tracks, could be served by both local and express trains.

- ^ Official landmark designations: NRHP stands for National Register of Historic Places and NYCL stands for New York City Landmark.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners Of The City of New York 1900–1901. New York City Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1902. pp. 6 v. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2023.