Nun

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2021) |

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation,[1] typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.[2] The term is often used interchangeably with religious sisters who do take simple vows[3] but live an active vocation of prayer and charitable work.

In Christianity, nuns are found in the Catholic, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, and Anglican and some Presbyterian traditions, as well as other Christian denominations.[1] In the Buddhist tradition, female monastics are known as Bhikkhuni, and take several additional vows compared to male monastics (bhikkhus). Nuns are most common in Mahayana Buddhism, but have more recently become more prevalent in other traditions.

Christianity

[edit]Catholicism

[edit]

In the Catholic tradition, there are many religious institutes of nuns and sisters (the female equivalent of male monks or friars), each with its own charism or special character. Traditionally, nuns are members of enclosed religious orders and take solemn religious vows, while sisters do not live in the papal enclosure and formerly took vows called "simple vows".[4]

As monastics, nuns living within an enclosure historically commit to recitation of the full Divine Office throughout the day in church, usually in a solemn manner. They were formerly distinguished within the monastic community as "choir nuns", as opposed to lay sisters who performed upkeep of the monastery or errands outside the cloister. This last task is still often entrusted to women, called "externs", who live in the monastery, but outside the enclosure. They were usually either oblates or members of the associated Third Order, often wearing a different habit or the standard woman's attire of the period.

Membership and vows

[edit]In general, when a woman enters a religious order or monastery she first undergoes a period of testing life for six months to two years called a postulancy. If she, and the order, determine that she may have a vocation to the life, she receives the habit of the order (usually with some modification, normally a white veil instead of black, to distinguish her from professed members) and undertakes the novitiate, a period (that lasts one to two years) of living the life of the religious institute without yet taking vows.[5] Upon completion of this period she may take her initial, temporary vows.[6] Temporary vows last one to three years, typically, and will be professed for not less than three years and not more than six.[7] Finally, she will petition to make her "perpetual profession", taking permanent, solemn vows.[8]

In the branches of the Benedictine tradition, (Benedictines, Cistercians, Camaldolese, and Trappists, among others) nuns take vows of stability (that is, to remain a member of a single monastic community), obedience (to an abbess or prioress), and conversion of life (which includes poverty and celibacy). In other traditions, such as the Poor Clares (the Franciscan Order) and the Dominican nuns, they take the threefold vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. These are known as the 'evangelical counsels' as opposed to 'monastic vows' proper. Most orders of nuns not listed here follow one of these two patterns, with some Orders taking an additional vow related to the specific work or character of their Order (for example, to undertake a certain style of devotion, praying for a specific intention or purpose).[9][10]

Cloistered nuns (Carmelites, for example) observe "papal enclosure"[11] rules, and their nunneries typically have walls separating the nuns from the outside world. The nuns rarely leave (except for medical necessity or occasionally for purposes related to their contemplative life) though they may receive visitors in specially built parlors, often with either a grille or half-wall separating the nuns from visitors. They are usually self-sufficient, earning money by selling jams, candies or baked goods by mail order, or by making liturgical items (such as vestments, candles, or hosts to be consecrated at Mass for Holy Communion).

They often undertake contemplative ministries – that is, a community of nuns is often associated with prayer for some particular good or supporting the missions of another order by prayer (for instance, the Dominican nuns of Corpus Christi Monastery in the Bronx, New York, pray in support of the priests of the Archdiocese of New York). Yet religious sisters can also perform this form of ministry, e.g., the Maryknoll Missionary Sisters have small houses of contemplative sisters, some in mission locations, who pray for the work of the priests, brothers, and other sisters of their congregation, and since Vatican II have added retreat work and spiritual guidance to their apostolate;[12] the Sister Disciples of the Divine Master are also cloistered sisters who receive visitors and pray in support of their sister congregation,[13] the Daughters of St. Paul in their media ministry.

Leadership

[edit]A canoness is a nun who corresponds to the male equivalent of canon, usually following the Rule of St. Augustine. The origin and rules of monastic life are common to both. As with the canons, differences in the observance of rule gave rise to two types: the canoness regular, taking the traditional religious vows, and the secular canoness, who did not take vows and thus remained free to own property and leave to marry, should they choose. This was primarily a way of leading a pious life for the women of aristocratic families and generally disappeared in the modern age, except for the modern Lutheran convents of Germany.

A nun who is elected to head her religious house is termed an abbess if the house is an abbey, a prioress if it is a monastery, or more generically may be referred to as "Mother Superior" and styled "Reverend Mother". The distinction between abbey and monastery has to do with the terms used by a particular order or by the level of independence of the religious house. Technically, a convent is any home of a community of sisters – or, indeed, of priests and brothers, though this term is rarely used in the United States. The term "monastery" is often used by The Benedictine family to speak of the buildings and "convent" when referring to the community. Neither is gender specific. 'Convent' is often used of the houses of certain other institutes.

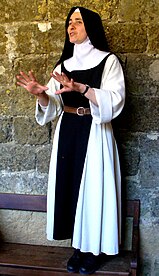

The traditional dress for women in religious communities consists of a tunic, which is tied around the waist with a cloth or leather belt. Over the tunic some nuns wear a scapular which is a garment of long wide piece of woolen cloth worn over the shoulders with an opening for the head. Some wear a white wimple and a veil, the most significant and ancient aspect of the habit. Some orders – such as the Dominicans – wear a large rosary on their belt. Benedictine abbesses wear a cross or crucifix on a chain around their neck.

After the Second Vatican Council, many religious institutes chose in their own regulations to no longer wear the traditional habit and did away with choosing a religious name. Catholic Church canon law states: "Religious are to wear the habit of the institute, made according to the norm of proper law, as a sign of their consecration and as a witness of poverty."[14]

Distinction between a nun and a religious sister

[edit]Although usage has varied throughout church history, typically "nun" (Latin: monialis) is used for women who have taken "solemn" vows, and "sister" (Latin: soror) is used for women who have taken "simple" vows (that is, vows other than solemn vows).

During the first millennium, nearly all religious communities of men and women were dedicated to prayer and contemplation. These monasteries were built in remote locations or were separated from the world by means of a precinct wall. The mendicant orders, founded in the 13th century, combined a life of prayer and dedication to God with active works of preaching, hearing confessions, and service to the poor, and members of these orders are known as friars rather than monks. At that time, and into the 17th century, Church custom did not allow women to leave the cloister if they had taken religious vows. Female members of the mendicant orders (Dominican, Augustinian and Carmelite nuns and Poor Clares) continued to observe the same enclosed life as members of the monastic orders.[15]

Originally, the vows taken by profession in any religious institute approved by the Holy See were classified as solemn.[11][16] This was declared by Pope Boniface VIII (1235–1303).[17] The situation changed in the 16th century. In 1521, two years after the Fourth Lateran Council had forbidden the establishment of new religious institutes, Pope Leo X established a religious Rule with simple vows for those tertiaries attached to existing communities who undertook to live a formal religious life. In 1566 and 1568, Pope Pius V rejected this class of congregation, but they continued to exist and even increased in number. After at first being merely tolerated, they afterwards obtained approval.[16] Finally in the 20th century, Pope Leo XIII recognized as religious all men and women who took simple vows.[18] Their lives were oriented not to the ancient monastic way of life, but more to social service and to evangelization, both in Europe and in mission areas. Their number had increased dramatically in the upheavals brought by the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic invasions of other Catholic countries, depriving thousands of religious of the income that their communities held because of inheritances and forcing them to find a new way of living the religious life. But members of these new associations were not recognized as "religious" until Pope Leo XIII's Constitution "Conditae a Christo" of 8 December 1900.[19]

The 1917 Code of Canon Law reserved the term "nun" (Latin: monialis) for religious women who took solemn vows or who, while being allowed in some places to take simple vows, belonged to institutes whose vows were normally solemn.[20] It used the word "sister" (Latin: soror) exclusively for members of institutes for women that it classified as "congregations"; and for "nuns" and "sisters" jointly it used the Latin word religiosae (women religious). The same religious order could include both "nuns" and "sisters", if some members took solemn vows and others simple vows.

The new legal code of the Catholic Church which was adopted in 1983, however, remained silent on this matter. Whereas previously the code distinguished between orders and congregations, the code now refers simply to religious institutes.

Since the code of 1983, the Vatican has addressed the renewal of the contemplative life of nuns. It produced the letter Verbi Sponsa in 1999,[21] the apostolic constitution Vultum Dei quaerere in 2016, and the instruction Cor Orans in 2018[22] "which replaced the 1999 document Verbi Sponsa and attempted to bring forward the ideas regarding contemplative life born during the Second Vatican Council".[23]

-

Sister Rosália Sehnem of the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity

-

A sister of the Theresienne Sisters of Basankusu wearing a brightly coloured habit, riding a motor-bike, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2013[24]

-

A Ugandan nun teaching during a community service day

United States

[edit]Nuns and sisters played a major role in American religion, education, nursing and social work since the early 19th century.[25] In Catholic Europe, convents were heavily endowed over the centuries, and were sponsored by the aristocracy. There were very few rich American Catholics, and no aristocrats. Religious orders were founded by entrepreneurial women who saw a need and an opportunity, and were staffed by devout women from poor families. The numbers grew rapidly, from 900 sisters in 15 communities in 1840, 50,000 in 170 orders in 1900, and 135,000 in 300 different orders by 1930. Starting in 1820, the sisters always outnumbered the priests and brothers.[26] Their numbers peaked in 1965 at 180,000 then plunged to 56,000 in 2010. Many women left their orders, and few new members were added.[27] Since the Second Vatican Council the sisters have directed their ministries more to the poor, working more directly among them and with them.[28]

Canada

[edit]Nuns have played an important role in Canada, especially in heavily Catholic Quebec. Outside the home, Canadian women had few domains which they controlled. An important exception came with Catholic nuns, especially in Québec. Stimulated by the influence in France, the popular religiosity of the Counter Reformation, new orders for women began appearing in the seventeenth century. In the next three centuries women opened dozens of independent religious orders, funded in part by dowries provided by the parents of young nuns. The orders specialized in charitable works, including hospitals, orphanages, homes for unwed mothers, and schools.[29]

Early modern Spain

[edit]Prior to women becoming nuns during early modern Spain, aspired nuns underwent a process. The process was ensured by the Council of Trent, which King Philip II (1556–1598) adopted within Spain.[30] King Phillip II acquired the aid of the Hieronymite order to ensure that monasteries abided by the decrees of the Council of Trent.[30] This changed the way in which nuns would live.[31] One edict of the Council of Trent was that female monasteries be enclosed in order to limit nuns' relationship with the secular world.[31] Enclosure of monasteries during this time was associated with chastity.[31] Another decree issued by the Council of Trent was that religious devotion be "true and voluntary".[31] A male clergy member would ask the aspiring nuns if whether or not their vocation was "true and voluntary" in order to ensure no enforced conversion.[31]

To be considered as a nun, one must have the economic means to afford the convent dowry.[32] During this time convent dowries were affordable, compared to secular marriages between a man and a woman.[33] Typically during early modern Spain many nuns were from elite families who had the means to afford the convent dowry and "maintenance allowances", which were annual fees.[32] Monasteries were economically supported through convent dowries.[32] Convent dowries could be waived if the aspiring nun had an artistic ability benefiting the monastery.[34]

Once an aspiring nun has entered the convent and has the economic means to afford the dowry, she undergoes the process of apprenticeship known as the novitiate period.[35] The novitiate period typically lasts 1–2 years, and during this time the aspiring nun lives the life of a nun without taking the official vows.[36] As she lives in the convent she is closely monitored by the other women in the community to determine if her vocation is genuine. This would be officially determined by a vote from the choir nuns.[32] If the aspiring nun passes the scrutiny of the women of the religious community, she then can make her solemn vows.[32] Prior to making the vows, the family of the nun is expected to pay the convent dowry.[32] Nuns were also expected to renounce their inheritance and property rights.[32]

Religious class distinctions:

- Choir nuns: Usually from elite families, they held office, could vote within the convent, and were given the opportunity to read and write.[37]

- Lay-sisters: Lower-class women, assigned tasks related to the labour of the convent, generally were not given the opportunities to read and write, and paid a lower dowry.[37]

Eastern Orthodox

[edit]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church there is no distinction between a monastery for women and one for men. In Greek, Russian, and other languages of primarily Christian Orthodox nations, both domiciles are called "monasteries" and the ascetics who live therein are "monastics". In English, however, it is acceptable to use the terms "nun" and "convent" for clarity and convenience. The term for an abbess is the feminine form of abbot (hegumen) – Greek: ἡγουμένη (hegumeni); Serbian: игуманија (igumanija); Russian: игумения (igumenia). Orthodox monastics do not have distinct "orders" as in Western Christianity. Orthodox monks and nuns lead identical spiritual lives.[38] There may be slight differences in the way a monastery functions internally but these are simply differences in style (Gr. typica) dependent on the abbess or abbot. The abbess is the spiritual leader of the convent and her authority is absolute (no priest, bishop, or even patriarch can override an abbess within the walls of her monastery). Abbots and Abbesses rank in authority equal to bishops in many ways and were included in ecumenical councils. Orthodox monasteries are usually associated with a local synod of bishops by jurisdiction, but are otherwise self-governing. Abbesses hear confessions (but do not absolve) and dispense blessings on their charges, though they still require the services of a presbyter (i.e., a priest) to celebrate the Divine Liturgy and perform other priestly functions, such as the absolution of a penitent.

In general, Orthodox monastics have little or no contact with the outside world, especially family. The pious family whose child decides to enter the monastic profession understands that their child will become "dead to the world" and therefore be unavailable for social visits.

There are a number of different levels that the nun passes through in her profession:

- Novice – When one enters a monastery the first three to five years are spent as a novice. Novices may or may not (depending on the abbess's wishes) dress in the black inner robe (Isorassa); those who do will also usually wear the apostolnik or a black scarf tied over the head (see photo, above). The isorassa is the first part of the monastic "habit" of which there is only one style for Orthodox monastics (this is true in general, there have been a few slight regional variations over the centuries, but the style always seems to precipitate back to a style common in the 3rd or 4th century). If a novice chooses to leave during the novitiate period no penalty is incurred.

- Rassaphore – When the abbess deems the novice ready, the novice is asked to join the monastery. If she accepts, she is tonsured in a formal service during which she is given the outer robe (Exorassa) and veil (Epanokamelavkion) to wear, and (because she is now dead to the world) receives a new name. Nuns consider themselves part of a sisterhood; however, tonsured nuns are usually addressed as "Mother" (in some convents, the title of "Mother" is reserved to those who enter into the next level of Stavrophore).

- Stavrophore – The next level for monastics takes place some years after the first tonsure when the abbess feels the nun has reached a level of discipline, dedication, and humility. Once again, in a formal service the nun is elevated to the "Little Schema" which is signified by additions to her habit of certain symbolic articles of clothing. In addition, the abbess increases the nun's prayer rule, she is allowed a stricter personal ascetic practice.

- Great Schema – The final stage, called "Megaloschemos" or "Great Schema" is reached by nuns whose Abbess feels they have reached a high level of excellence. In some monastic traditions the Great Schema is only given to monks and nuns on their death bed, while in others they may be elevated after as little as 25 years of service.

|

|

Protestantism

[edit]

After the Protestant Reformation, some monasteries in Lutheran lands (such as Amelungsborn Abbey near Negenborn and Loccum Abbey in Rehburg-Loccum) and convents (such as Ebstorf Abbey near the town of Uelzen and Bursfelde Abbey in Bursfelde) adopted the Lutheran Christian faith.[39] Other convents, especially those in Reformed areas, closed after the Reformation, with some sisters deciding to marry.

A modern resurgence of the early Christian Deaconess office for women began in Germany in the 1840s and spread through Scandinavia, Britain and the United States, with some elements of the religious life, such as simple vows, and a daily obligation of prayer. Lutherans were especially active, and within both Lutheranism and Anglicanism some Deaconesses formed religious communities, with community living, and the option of life vows in religion.[40] The modern movement reached a zenith about 1910, then slowly declined as secularization undercut religiosity in Europe, and the professionalization of nursing and social work offered better career opportunities for young women. A small movement still exists, and its legacy is seen in the names of numerous hospitals.[41]

The example of the Deaconess communities eventually led to the establishment of religious communities of monks and nuns within some Protestant traditions,[42] particularly those influenced by the more liturgical Protestant reformers (such as Martin Luther) rather than the more extreme reformers (such as John Calvin). This has allowed for communities of nuns (or, in some cases, mixed communities of nuns and monks) to be re-established in some Protestant traditions. Many of these are within the episcopal Lutheran tradition and the closeness of Lutheranism with Anglicanism in its belief and practice has led to local arrangements of inter-Communion between the two traditions, such as the Porvoo Communion.[43]

Lutheranism

[edit]

There are a plethora of religious orders within the Lutheran Churches, such as the Order of Lutheran Franciscans and Daughters of Mary. Nearly all active Lutheran orders are located in Europe.

The Evangelical Sisterhood of Mary, an order of Lutheran nuns, operates a guesthouse for Holocaust survivors in Jerusalem.[43]

Anglicanism

[edit]

Religious communities throughout England were destroyed by King Henry VIII when he separated the Church of England from papal authority during the English Reformation (see Dissolution of the Monasteries). Monasteries and convents were deprived of their lands and possessions, and monastics were forced to either live a secular life on a pension or flee the country. Many Catholic nuns went to France.

Anglican religious orders are organizations of laity or clergy in the Anglican Communion who live under a common rule. The term "religious orders" is distinguished from Holy Orders (the sacrament of ordination which bishops, priests, and deacons receive), though many communities do have ordained members.

The structure and function of religious orders in Anglicanism roughly parallels that which exists in Catholicism. Religious communities are divided into orders proper, in which members take solemn vows and congregations, whose members take simple vows.

With the rise of the Oxford Movement in Anglicanism in the early 19th century came interest in the revival of "religious life" in England. Between 1841 and 1855, several religious orders for nuns were founded, among them the Community of St. Mary at Wantage and the Society of Saint Margaret at East Grinstead.

In the United States and Canada, the founding of Anglican religious orders of nuns began in 1845 with the Sisterhood of the Holy Communion (now defunct) in New York.

Whilst there is no single central authority for all religious orders, and many member churches of the Anglican Communion have their own internal structures for recognising and regulating religious orders, some central functions are performed by the Anglican Religious Communities Department at Church House, Westminster, the headquarters of the Church of England's Church Commissioners, General Synod, Archbishops' Council, and National Society. This department publishes the biennial Anglican Religious Life, a world directory of religious orders, and also maintains an official Anglican Communion website for religious orders. Anglican Religious Life defines four categories of community.[44]

- "Traditional celibate religious orders and communities": Members take a vow of celibacy (amongst other vows) and follow a common Rule of life. They may be enclosed and contemplative or open and engaged in apostolic works.

- "Dispersed communities": These are orders or communities whose members, whilst taking vows (including celibacy), do not live together in community. In most cases the members are self-supporting and live alone, but follow the same Rule of life, and meet together frequently in assemblies often known as 'Chapter meetings'. In some cases some members may share a common life in very small groups of two or three.

- "Acknowledged communities": These communities live a traditional Christian life, including the taking of vows, but the traditional vows are adapted or changed. In many cases these communities admit both single and married persons as members, requiring celibacy on the part of those who are single, and unfailing commitment to their spouse on the part of married members. They also amend the vow of poverty, allowing personal possessions, but requiring high standards of tithing to the community and the wider church. These communities often have residential elements, but not full residential community life, as this would be incompatible with some elements of married family life.

- "Other communities": This group contains communities that are ecumenical (including Anglicans) or that belong to non-Anglican churches that have entered into relationships of full communion with the Anglican Church (particularly, but not only, certain Lutheran churches).

In the United States (only), there is a clear distinction between "orders" and "communities", as the Episcopal Church has its own two-fold definition of "religious orders" (equivalent to the first two groups above) and "Christian communities" (equivalent to the third group above).[45] The Anglican Religious Life directory affirms this, stating "This distinction in not used in other parts of the Anglican Communion where 'communities' is also used for those who take traditional vows."[46]

In some Anglican orders, there are sisters who have been ordained and can celebrate the Eucharist.[47]

Presbyterian

[edit]The Emmanuel Sisterhood in Cameroon, Africa, is part of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon (PCC).[48][better source needed]

Methodism

[edit]The Saint Brigid of Kildare Benedictine Monastery is a United Methodist double monastery with both monks and nuns.[49]

Buddhism

[edit]

| People of the Pāli Canon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All Buddhist traditions have nuns, although their status is different among Buddhist countries. The Buddha is reported to have allowed women into the sangha only with great reluctance, predicting that the move would lead to Buddhism's collapse after 500 years, rather than the 1,000 years it would have enjoyed otherwise. (This prophecy occurs only once in the Canon and is the only prophecy involving time in the Canon, leading some to suspect that it is a late addition.)[50] Fully ordained Buddhist nuns (bhikkhunis) have more Patimokkha rules than the monks (bhikkhus). The important vows are the same, however.

As with monks, there is quite a lot of variation in nuns' dress and social conventions between Buddhist cultures in Asia. Chinese nuns possess the full bhikkuni ordination, Tibetan nuns do not. In Theravada countries it is generally believed that the full ordination lineage of bhikkunis died out, though in many places they wear the "saffron" colored robes, observing only ten precepts like novices.

Thailand

[edit]In Thailand, a country which never had a tradition of fully ordained nuns (bhikkhuni), there developed a separate order of non-ordained female renunciates called mae chi. However, some of them have played an important role in dhamma-practitioners' community. There are in Thai Forest Tradition foremost nuns such as Mae Ji Kaew Sianglam, the founder of the Nunnery of Baan Huai Saai, who is believed by some to be enlightened[51] as well as Upasika Kee Nanayon.[52] At the beginning of the 21st century, some Buddhist women in Thailand have started to introduce the bhikkhuni sangha in their country as well, even if public acceptance is still lacking.[53] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni,[54] formerly the successful academic scholar Dr. Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, established a controversial monastery for the training of Buddhist nuns in Thailand.[55]

Taiwan

[edit]The relatively active roles of Taiwanese nuns were noted by some studies. Researcher Charles Brewer Jones estimates that from 1951 to 1999, when the Buddhist Association of the ROC organized public ordination, female applicants outnumbered males by about three to one. He adds:

All my informants in the areas of Taipei and Sanhsia considered nuns at least as respectable as monks, or even more so. [...] In contrast, however, Shiu-kuen Tsung found in Taipei county that female clergy were viewed with some suspicion by society. She reports that while outsiders did not necessarily regard their vocation as unworthy of respect, they still tended to view the nuns as social misfits.[56]

Wei-yi Cheng studied the Luminary (Hsiang Kuang 香光) order in southern Taiwan. Cheng reviewed earlier studies which suggest that Taiwan's Zhaijiao tradition has a history of more female participation, and that the economic growth and loosening of family restriction have allowed more women to become nuns. Based on studies of the Luminary order, Cheng concluded that the monastic order in Taiwan was still young and gave nuns more room for development, and more mobile believers helped the order.[57]

Tibet

[edit]The August 2007 International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha, with the support of the XIVth Dalai Lama, reinstated the Gelongma (Dharmaguptaka vinaya bhikkhuni) lineage, having been lost, in India and Tibet, for centuries. Gelongma ordination requires the presence of ten fully ordained people keeping exactly the same vows. Because ten nuns are required to ordain a new one, the effort to establish the Dharmaguptaka bhikkhu tradition has taken a long time.

It is permissible for a Tibetan nun to receive bhikkhuni ordination from another living tradition, e.g., in Vietnam. Based on this, Western nuns ordained in Tibetan tradition, like Thubten Chodron, took full ordination in another tradition.

The ordination of monks and nuns in Tibetan Buddhism distinguishes three stages: rabjung-ma, getshül-ma and gelong-ma. The clothes of the nuns in Tibet are basically the same as those of monks, but there are differences between novice and gelong robes.

Japan

[edit]Hokke-ji in 747 was established by the consort of the Emperor. It took charge of provincial convents, performed ceremonies for the protection of the state, and became the site of pilgrimages. Aristocratic Japanese women often became Buddhist nuns in the premodern period. Originally it was thought they could not gain salvation because of the Five Hindrances, which said women could not attain Buddhahood until they changed into men. However, in 1249, 12 women received full ordination as priests.[58]

See also

[edit]- Catholic religious order

- Consecrated virgin

- Deaconess, Protestant religious women

- Miko, a Japanese priestess

- Monasticism

- Monk, the male monastic

- Category:Nunsploitation films

- Priest

- Religious sister

- Sādhvī, Hinduist religious women

References

[edit]- ^ a b "What is a Nun? (with pictures)". www.wise-geek.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary, vol. X, page 599.

- ^ "Sister". Merriam-Webster. 26 May 2024.

[A] member of a women's religious order (as of nuns or deaconesses); especially : one of a Roman Catholic congregation under simple vows

- ^ "What is the difference between a sister and a nun?". anunslife.org. Archived from the original on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ Canon 648 Archived 2020-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, CIC 1983

- ^ Canon 656 Archived 2017-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, CIC 1983

- ^ Canon 655 Archived 2017-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, CIC 1983

- ^ Canon 657 Archived 2017-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, CIC 1983

- ^ a b "Mother Teresa, who becomes a saint on Sunday, began her life as a nun in Dublin". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ a b "Nun in iconic Italy quake photo shares her story of survival". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ a b Canon 667 Archived 2020-03-12 at the Wayback Machine §3, CIC 1983, SCRIS instruction, "Venite seorsum" August 15, 1969, in AAS 61 (1969) 674–690

- ^ "Sister Grace Corde Myerjack – Maryknoll Sisters". Maryknoll Sisters. Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Vocation: Sister Disciples Of The Divine Master". www.pddm.us. Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law – IntraText". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2018-02-20. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Mary Ward". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2021-09-04. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ a b Arthur Vermeersch, "Religious Life" Archived 2012-01-15 at the Wayback Machine in The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. Accessed 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Illud solum votum debere dici solemne ... quod solemnizatum fuerit per suceptionem S. Ordinis aut per professionem expressam vel tacitam factam alicui de religionibus per Sedem Apostolicam approbatis" (C. unic. de voto, tit. 15, lib. III in 6, quoted in Celestine Anthony Freriks, Religious Congregations in Their External Relations, p. 17).

- ^ Constitution "Conditae a Christo" of 8 December 1900, cited in Mary Nona McGreal, Dominicans at Home in a New Nation, chapter 11 Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cited in Mary Nona McGreal, Dominicans at Home in a New Nation, chapter 11 Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "CIC 1917: text – IntraText CT". www.intratext.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Verbi Sponsa (13 May 1999)". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ^ ""Cor Orans" – Implementing Instruction of the Apostolic Constitution "Vultum Dei quaerere" on women's contemplative life, of the Congregation for the Institutes of Consecrated Life and the Societies of Apostolic Life (1 April 2018)". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2018-11-02. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ^ "Contemplative nuns roll with the changes under Pope Francis". Crux. 2018-11-22. Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ^ "The Theresienne Sisters of Basankusu (La congrégation des soeurs thérésiennes de Basankusu)". Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- ^ Margaret M. McGuinness, Called to Serve: A History of Nuns in America (2015) excerpt Archived 2017-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Toole, James M. (2008). The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America. Harvard University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780674034884.

- ^ Margaret M. McGuinness, Called to Serve (2013), ch 8

- ^ "Sisters of Mercy: Spirituality, Resources, Prayer and Action". Sisters of Mercy. Archived from the original on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ Thomas Carr, Jr., "Writing the Convent in New France: The Colonialist Rhetoric of Canadian Nuns", Quebec Studies (2009), Issue 47, pp 3–23.

- ^ a b Schmitz, Timothy J. (2006-01-01). "The Spanish Hieronymites and the Reformed Texts of the Council of Trent". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 37 (2): 375–399. doi:10.2307/20477841. JSTOR 20477841.

- ^ a b c d e Lehfeldt, Elizabeth A. (1999-01-01). "Discipline, Vocation, and Patronage: Spanish Religious Women in a Tridentine Microclimate". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 30 (4): 1009–1030. doi:10.2307/2544609. JSTOR 2544609.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lehfeldt, Elizabeth A. (2000-01-01). "Convents as Litigants: Dowry and Inheritance Disputes in Early-Modern Spain". Journal of Social History. 33 (3): 645–664. doi:10.1353/jsh.2000.0027. JSTOR 3789215. S2CID 144464752. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ Evangelisti, Silvia (2007). Nuns: A history of convent life, 1450–1700. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press.

- ^ Taggard, Mindy Nancarrow (2000-01-01). "Art and Alienation in Early Modern Spanish Convents". South Atlantic Review. 65 (1): 24–40. doi:10.2307/3201923. JSTOR 3201923.

- ^ Lavrin, Asuncion (2008). Brides of Christ: Conventual life in colonial Mexico. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008. p. 49.

- ^ Lavrin, Asuncion (2008). Brides of Christ: Conventual life in colonial Mexico. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. p. 48.

- ^ a b Evangelisti, Silvia (2007). Nuns: A history of convent life, 1450–1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 30.

- ^ Archpriest Seraphim Slobodskoy, The Law of God (Printshop of St. Job of Pochaev, Jordanville, NY, ISBN 0884650448), p. 618.

- ^ "Kloster Ebstorf". Medieval Histories. 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

The monastery is mentioned for the first time in 1197. It belongs to the group of so-called Lüneklöstern (monasteries of Lüne), which became Lutheran convents following the Protestant Reformation. […] It is currently one of several Lutheran convents maintained by the Monastic Chamber of Hanover (Klosterkammer Hannover), an institution of the former Kingdom of Hanover founded by its Prince-Regent, later King George IV of the United Kingdom, in 1818, in order to manage and preserve the estates of Lutheran convents.

- ^ See CSA history here Archived 2011-06-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cynthia A. Jurisson, "The Deaconess Movement", in Rosemary Skinner Keller et al., eds. Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America (Indiana U.P., 2006). pp. 821–33 online

- ^ One example of a Protestant religious order Archived 2014-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Israeli press report concerning one German Lutheran order Archived 2014-08-24 at the Wayback Machine of nuns.

- ^ Anglican Religious Life 2012–13, published Canterbury Press, Norwich, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84825-089-5, pp. iii, iv, 19, 147, 151, 171.

- ^ See Title III, Canon 24, sections 1 and 2 of the Canons of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, also quoted at Anglican Communion Religious Communities Archived 2015-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Anglican Religious Life 2012–13, Canterbury Press, Norwich, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84825-089-5, p. 151.

- ^ What We Do Archived 2010-06-16 at the Wayback Machine sisters of St. Margaret, (Episcopal religious community of women)

- ^ "Ihre Homepage - HOME PAGE". www.emmanuel-sisterhood.org (in German). Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Patricia Lefevere. Methodist woman founds monastery. National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

St. Brigid's oblate group has grown to 16 members since the dedication of the monastery on St. Brigid's feast in 2000. Besides Stamps, it counts another 13 United Methodists, one Catholic and one Disciples of Christ member. The ages of group members range from 23 to 82. One-third of them are men; half are ordained. The community continues to grow.

- ^ Hellmuth Hecker, [1] Archived 2007-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Mae Chee Kaew – Her Journey to Spiritual Awakening & Enlightenment e-book" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Upasika Kee Nanayon and the Social Dynamic of Theravadin Buddhist Practice". Archived from the original on October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Issues | Authoritarianism of the holy kind". www.buddhistchannel.tv. Archived from the original on 2022-12-14. Retrieved 2022-12-14.

- ^ "Bhikkhuni Dhammananda". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ Thai Bhikkhunis – Songdhammakalyani Monastery Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles Brewer Jones, Buddhism in Taiwan: Religion and the State, 1660–1990; University of Hawaii Press, 1999; pp. 154–155

- ^ Cheng, Wei-yi. "Luminary Buddhist Nuns in Contemporary Taiwan: A Quiet Feminist Movement". Journal of Buddhist Ethics (V. 10 (2003)). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-06-05.

- ^ Lori Meeks, Hokkeji and the Reemergence of Female Monastic Orders in Premodern Japan (2010) excerpt and text search Archived 2017-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Arai, Paula Kane Robinson (1999). Women Living Zen: Japanese Soto Buddhist Nuns.

- Bechert, Heinz; Gombrich, Richard Francis (1991). The World of Buddhism: Buddhist Monks and Nuns in Society and Culture.

- Lohuis, Elles (2013). Glocal Place, Lived Space: Everyday Life in a Tibetan Buddhist Monastery for Nuns in Northern India.

- Catholics

- Chadwick, Owen (1981). The Popes and European Revolution. Clarendon Press. pp. 211–52. ISBN 9780198269199. also online[permanent dead link]

- Curtis, Sarah A. (2016). "The Double Invisibility of Missionary Sisters". Journal of Women's History. 28 (4): 134–143. doi:10.1353/jowh.2016.0037. S2CID 151828886. Deals with French nuns in the 19th century.

- Kennedy, Teresa (1991). Women Religious in the Church: a directory of individual orders / institutes. Southport: Gowland. ISBN 1-872480-14-4.

- McGuinness, Margaret M. (2013). Called to Serve: A History of Nuns in America. New York University Press. 266 pages

- McNamara, Jo Ann Kay (1998). Sisters in Arms: Catholic Nuns through Two Millennia. Excerpt and text search

- O’Brien, Anne (2016). "Catholic nuns in transnational mission, 1528–2015". Journal of Global History. 11 (3): 387–408. doi:10.1017/S1740022816000206.

- Power, Eileen (1922). Medieval English Nunneries c. 1275 to 1535. Cambridge University Press – via Internet Archive.

- Roberts, Rebecca (2013). "Le Catholicisme au féminin: Thirty Years of Women's History". Historical Reflections. 39 (1): 82–100. On France, especially research on Catholic nuns by Claude Langlois

- Shank, Lillian Thomas; Nichols, John A., eds. (1987). Medieval Religious Women: Peaceweavers.

- Veale, Ailish (2016). "International and Modern Ideals in Irish Female Medical Missionary Activity, 1937–1962". Women's History Review. 25 (4): 602–618. doi:10.1080/09612025.2015.1114330. S2CID 148045770.

- Williams, Maria Patricia (2015). "Mobilising Mother Cabrini's educational practice: the transnational context of the London school of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus 1898–1911". History of Education. 44 (5): 631–650. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2015.1063711. S2CID 148067468.

External links

[edit]- Monastic Matrix: A Scholarly Resource for the Study of Women's Religious Communities 400–1600 C.E. Archived 2007-06-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Full text + illustrations, The Hermits and Anchorites of England by Rotha Mary Clay

- Nuns of Medieval England, full text + illustrations

- Religious Orders including Female Religious, full text + illustrations

- Medieval Shrines of British Saints, including sainted women religious, full text + illustrations

- Nuns article from The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Instruction on the Contemplative Life and on the Enclosure of Nuns Verbi Sponsa of the Vatican's Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and for Societies of Apostolic Life

- A Biography of a Vajrayana Buddhist Nun

- Martin Luther's letter To Several Nuns, August 6, 1524 Archived December 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (two reasons life at the convent and vows may be forsaken)

- Sakyadhita – The International Association of Buddhist Women

- The Carmelite Sisters

![A sister of the Theresienne Sisters of Basankusu wearing a brightly coloured habit, riding a motor-bike, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2013[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/Nun_on_a_motor-bike_2_-_by_Francis_Hannaway.jpg/200px-Nun_on_a_motor-bike_2_-_by_Francis_Hannaway.jpg)