Federal Reserve Bank

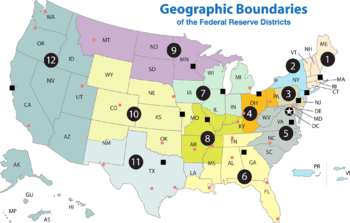

A Federal Reserve Bank is a regional bank of the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States. There are twelve in total, one for each of the twelve Federal Reserve Districts that were created by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.[1] The banks are jointly responsible for implementing the monetary policy set forth by the Federal Open Market Committee, and are divided as follows:

- Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

- Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

- Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

- Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Some banks also possess branches, with the whole system being headquartered at the Eccles Building in Washington, D.C.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

The Federal Reserve Banks are the most recent institutions that the United States government has created to provide functions of a central bank. Prior institutions have included the First (1791–1811) and Second (1818–1824) Banks of the United States, the Independent Treasury (1846–1920) and the National Banking System (1863–1935). Several policy questions have arisen with these institutions, including the degree of influence by private interests, the balancing of regional economic concerns, the prevention of financial panics, and the type of reserves used to back currency.[2]

A financial crisis known as the Panic of 1907 threatened several New York banks with failure, an outcome avoided through loans arranged by banker J. P. Morgan. Morgan succeeded in restoring confidence to the New York banking community, but the panic revealed weaknesses in the U.S. financial system, such that a private banker could dictate the terms of a bank's survival.[3] In other parts of the country, clearing houses briefly issued their own money notes to carry on business. In response, Congress formed the National Monetary Commission to investigate options for providing currency and credit in future panics. Based on the Commission's findings and other proposals, Congress established the Federal Reserve System in which several Federal Reserve Banks would provide liquidity to banks in different regions of the country.[2] The Federal Reserve Banks opened for business in November 1914.[4]

Legal status

[edit]The Reserve Banks are organized as self-financing corporations and empowered by Congress to distribute currency and regulate its value under policies set by the Federal Open Market Committee and the Board of Governors. Their corporate structure reflects the concurrent interests of the government and the member banks, but neither of these interests amounts to outright ownership.

Legal cases involving the Federal Reserve Banks have concluded that they are "private", but can be held or deemed as "governmental" depending on the particular law at issue. In United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation v. Western Union Telegraph Co.,[5] the U.S. Supreme Court stated, "Instrumentalities like the national banks or the federal reserve banks, in which there are private interests, are not departments of the government. They are private corporations in which the government has an interest." The United States has an interest in the Federal Reserve Banks as tax-exempt federally created instrumentalities whose profits belong to the federal government, but this interest is not proprietary.[6] In Lewis v. United States,[7] the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit stated that: "The Reserve Banks are not federal instrumentalities for purposes of the FTCA [the Federal Tort Claims Act], but are independent, privately owned and locally controlled corporations." The opinion went on to say, however, that: "The Reserve Banks have properly been held to be federal instrumentalities for some purposes," such as anti-bribery law. Another relevant decision is Scott v. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,[6] in which the distinction is made between Federal Reserve Banks, which are federally created instrumentalities, and the Board of Governors, which is a federal agency.

The original Federal Reserve Act provided starting capital for the Reserve Banks by requiring the participating banks to purchase stock in a Reserve Bank in proportion to their assets. This stock pays a dividend out of the Reserve Bank's earnings but otherwise is quite different from common stock in a private corporation. It may not be traded, transferred or borrowed against, and it grants no ownership of the Reserve Bank's surplus.[8] A bank's stock ownership does not give it proportional voting power to choose the Reserve Bank's directors; instead, each member bank receives three ranked votes for six of the Reserve Bank's nine directors, who are subject to qualifications defined in the Federal Reserve Act. If a Reserve Bank were ever dissolved or liquidated, the Act states that members would be eligible to redeem their stock up to its purchase value, while any remaining surplus would belong to the federal government.[9]

Regarding the structural relationship between the twelve Federal Reserve banks and the commercial (member) banks, political science professor Michael D. Reagan explains that,[10]

the "ownership" of the Reserve Banks by the commercial banks is symbolic; they do not exercise the proprietary control associated with the concept of ownership nor share, beyond the statutory dividend, in Reserve Bank "profits." ... Bank ownership and election at the base are therefore devoid of substantive significance, despite the superficial appearance of private bank control that the formal arrangement creates.

Function

[edit]The Federal Reserve Banks offer various services to the federal government and the private sector:[11][12]

- Acting as depositories for bank reserves

- Lending to banks to cover short-term fund deficits, seasonal business cycles, or extraordinary liquidity demands (i.e. runs)

- Collecting and clearing payments between banks

- Issuing banknotes for general circulation as currency

- Administering the deposit accounts of the federal government

- Conducting auctions and buybacks of federal debt

- Purchasing obligations of non-bank entities via emergency credit facilities authorized by the Board of Governors

Historically the Reserve Banks compensated member banks for keeping reserves on deposit (and therefore unavailable for lending) by paying them a dividend from earnings, limited by law to 6 percent. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA) of 2008 additionally authorized the Reserve Banks to pay interest on member bank reserves, while the FAST Act of 2015 imposed an additional dividend limit equal to the yield determined in the most recent 10-year Treasury Note auction.

Although all Reserve Banks have the legal authority to conduct open-market operations, in practice only the Reserve Bank of New York does so. It manages the System Open Market Account (SOMA), a portfolio of government-issued or government-guaranteed securities that is shared among all of the Reserve Banks.[13]

Finances

[edit]The Federal Reserve Banks fund their own operations, primarily by distributing the earnings from the System Open Market Account. Expenses and dividends paid are typically a small fraction of a Federal Reserve Bank's revenue each year.[14] The banks may retain part of their earnings in their own surplus funds that are limited to $7.5 billion, system-wide. The rest must be transferred via the Board of Governors to the Secretary of the Treasury, who then deposits it to the Treasury's general fund.[15][16] When a Reserve Bank's earnings are insufficient to cover its expenses and dividends, it introduces a deferred asset on its books to be realized from future earnings.[17]

The Reserve Banks were historically capitalized through deposits of gold, and in 1933 all privately held monetary gold was transferred to them under Executive Order 6102. This gold was in turn transferred to the Treasury under the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 in exchange for gold certificates that may not be redeemed under current law. The Reserve Banks continue to report these certificates as assets, but they do not represent direct gold ownership and the Board of Governors has stated that "the Federal Reserve does not own gold."[18]

Although the Reserve Banks operate as distinct financial entities, they participate each April in an interdistrict settlement process that has three purposes: settling the payment balances that the Reserve Banks owe each other; allocating ownership of the SOMA portfolio; and establishing uniform gold certificate backing for Federal Reserve Notes. This process connects the Reserve Banks' different functions – monetary policy, payment clearing and currency issue – as an integrated system.[19]

The Federal Reserve Banks conduct ongoing internal audits of their operations to ensure that their accounts are accurate and comply with the Federal Reserve System's accounting principles. The banks are also subject to two types of external auditing. Since 1978 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has conducted regular audits of the banks' operations. The GAO audits are reported to the public, but they may not review a bank's monetary policy decisions or disclose them to the public.[20] Since 1999 each bank has also been required to submit to an annual audit by an external accounting firm,[21] which produces a confidential report to the bank and a summary statement for the bank's annual report. Some members of Congress continue to advocate a more public and intrusive GAO audit of the Federal Reserve System,[22] but Federal Reserve representatives support the existing restrictions to prevent political influence over long-range economic decisions.[23][24]

Banks

[edit]

The Federal Reserve officially identifies Districts by number and Reserve Bank city.[25]

- 1st District (A): Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

- 2nd District (B): Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- 3rd District (C): Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

- 4th District (D): Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, with branches in Cincinnati, Ohio and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 5th District (E): Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, with branches in Baltimore, Maryland and Charlotte, North Carolina

- 6th District (F): Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, with branches in Birmingham, Alabama; Jacksonville, Florida; Miami, Florida; Nashville, Tennessee; and New Orleans, Louisiana

- 7th District (G): Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, with a branch in Detroit, Michigan.[26]

- 8th District (H): Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, with branches in Little Rock, Arkansas; Louisville, Kentucky; and Memphis, Tennessee

- 9th District (I): Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, with a branch in Helena, Montana

- 10th District (J): Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, with branches in Denver, Colorado; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and Omaha, Nebraska

- 11th District (K): Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, with branches in El Paso, Texas; Houston, Texas; and San Antonio, Texas

- 12th District (L): Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, with branches in Los Angeles, California; Portland, Oregon; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Seattle, Washington

The New York Federal Reserve district is the largest by asset value. San Francisco, followed by Kansas City and Minneapolis, represent the largest geographical districts. Missouri is the only state to have two Federal Reserve Banks (Kansas City and St. Louis). California, Florida, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas are the only states which have two or more Federal Reserve Bank branches seated within their states, with Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee having branches of two different districts within the same state. In the 12th District, the Seattle Branch serves Alaska, and the San Francisco Bank serves Hawaii. New York, Richmond, and San Francisco are the only banks that oversee non-U.S. state territories. The System serves these territories as follows: the New York Bank serves the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands; the Richmond Bank serves the District of Columbia; the San Francisco Bank serves American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. The Board of Governors last revised the branch boundaries of the System in February 1996.[25]

Assets

[edit]| Federal Reserve Bank | Total assets[27] in billions USD |

|---|---|

| New York City | 4,155 |

| San Francisco | 820 |

| Richmond | 651 |

| Atlanta | 493 |

| Chicago | 411 |

| Dallas | 336 |

| Cleveland | 288 |

| Boston | 183 |

| St. Louis | 114 |

| Philadelphia | 111 |

| Kansas City | 96 |

| Minneapolis | 54 |

| All banks | 7713 |

List of current presidents and CEOs of Federal Reserve Banks

[edit]| Federal Reserve Bank | Commonly known as | Incumbent president & CEO | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York City | New York Fed | John Williams | Vice Chairman, Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)[28]

Permanent FOMC Member |

| San Francisco | San Francisco Fed | Mary C. Daly | 2023 FOMC Alternate Member 2024 FOMC Member |

| Atlanta | Atlanta Fed | Raphael Bostic | 2023 FOMC Alternate Member 2024 FOMC Member |

| Richmond | Richmond Fed | Thomas Barkin | 2023 FOMC Alternate Member 2024 FOMC Member |

| Chicago | Chicago Fed | Austan Goolsbee | 2022 FOMC Alternate Member 2023 FOMC Member 2024 FOMC Alternate Member 2025 FOMC Member |

| Dallas | Dallas Fed | Lorie K. Logan | 2022 FOMC Alternate Member 2023 FOMC Member |

| Cleveland | Cleveland Fed | Beth M. Hammack | 2024 FOMC Member 2025 FOMC Alternate Member |

| Philadelphia | Philly Fed | Patrick Harker | 2022 FOMC Alternate Member 2023 FOMC Member |

| Boston | Boston Fed | Susan M. Collins | 2024 FOMC Alternate Member 2025 FOMC Member |

| St. Louis | St. Louis Fed | Alberto G. Musalem | 2024 FOMC Alternate Member 2025 FOMC Member |

| Kansas City | Kansas City Fed | Jeffrey R. Schmid | 2022 FOMC Member 2024 FOMC Alternate Member 2025 FOMC Member |

| Minneapolis | Minneapolis Fed | Neel Kashkari | 2022 FOMC Alternate Member 2023 FOMC Member |

See also

[edit]- Chair of the Federal Reserve

- Criticism of the Federal Reserve

- Federal funds rate

- Federal Reserve Act

- List of Federal Reserve branches

- List of regions of the United States#Federal Reserve Banks

Citations

[edit]- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 417. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ a b Wells, Donald R. (2004). The Federal Reserve System: A History. ISBN 9780786418800.

- ^ Carroso, Vincent P. The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913

- ^ The Founding of the Fed

- ^ "UNITED STATES SHIPPING BOARD EMERGENCY FLEET CORP. v. WESTERN U." Find Law. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Kennedy C. Scott v. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, et al., 406 F.3d 532 Archived May 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (8th Cir. 2005).

- ^ 680 F.2d 1239 Archived May 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (9th Cir. 1982).

- ^ "FRB: FAQs: Banking Information". Federalreserve.gov. February 12, 2006. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ : Use of earnings transferred to the Treasury

- ^ Michael D. Reagan, "The Political Structure of the Federal Reserve System," American Political Science Review, Vol. 55 (March 1961), pp. 64-76, as reprinted in Money and Banking: Theory, Analysis, and Policy, p. 153, ed. by S. Mittra (Random House, New York, 1970).

- ^ United States Government Manual: Federal Reserve System

- ^ Treasury Debt Auctions and Buybacks as Fiscal Agent

- ^ 2018 Combined Financial Statements (Note 5: System Open Market Account)

- ^ Annual reports

- ^ 12 U.S.C. § 289

- ^ See bank financial statements, e.g. 2018 Combined Financial Statements (Operating Expenses: Earnings remittances to the Treasury), and Treasury financial reports, e.g. 2018 Agency Financial Report (Sources of Custodial Revenue: Deposit of Earnings, Federal Reserve System)

- ^ Carpenter, Seth B.; Ihrig, Jane E.; Klee, Elizabeth C.; Quinn, Danel W.; Boote, Alexander H. (January 2013). The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and Earnings: A primer and projections (PDF) (Report). Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ "Does the Federal Reserve own or hold gold?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Wolman, Alexander L. (2013). "Federal Reserve Interdistrict Settlement". Economic Quarterly. 99 (2). Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ 31 U.S.C. § 714

- ^ 12 U.S.C. § 269b

- ^ Zumbrun, Joshua (July 21, 2009). "Bernanke Fights Audit Threat To The Fed". Forbes. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ "How the Federal Reserve is Audited". Federal Reserve Bank of New York. April 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ Powell, Jerome H. (February 9, 2015). "'Audit the Fed' and Other Proposals". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ a b "The Twelve Federal Reserve Districts". Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve Board. December 13, 2005. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "About Us - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago". www.chicagofed.org. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "Factors Affecting Reserve Balances". federalreserve.gov. December 28, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Fed - Federal Open Market Committee". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (May 1914). "The March of Events: The Federal Reserve Districts". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV (1): 10–11. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

The first new piece of machinery for the new currency system is now provided.