Fatherland (novel)

Cover of the first UK edition | |

| Author | Robert Harris |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Thriller, alternate history |

| Publisher | Hutchinson |

Publication date | 7 May 1992 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 372 (first edition, hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-09-174827-5 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 26548520 |

Fatherland is a 1992 alternative history detective novel by English writer and journalist Robert Harris. Set in a world where the Axis won World War II, the story's protagonist- Xavier March- is an officer of the Kripo, the criminal police, who is investigating the murder of a Nazi government official who participated at the Wannsee Conference. A plot is thus discovered to eliminate all of those who attended the conference, to help improve German relations with the United States.

The novel subverts some of the conventions of the detective novel. It begins with a murder and diligent police detective investigating and eventually solving it. However, since the murderer is highly placed in the Nazi regime, solving the mystery does not result in the detective pursuing and arresting the murderer. The contrary occurs: the murderer pursuing and arresting the detective.

The novel was an immediate best-seller in the UK and has sold over three million copies and been translated into 25 languages.

Plot

[edit]The novel opens in Nazi Germany in April 1964 during the week leading up to the 75th birthday of Adolf Hitler,[note 1] Detective Xavier March is an investigator working for the Kriminalpolizei (Kripo), as he investigates the suspicious death of a high-ranking Nazi, Josef Bühler, in the Havel on the outskirts of Berlin. As March uncovers more details, he realises that he is caught up in a political scandal involving senior Nazi Party officials, who are apparently being systematically murdered under staged circumstances. As soon as the body is identified, the Gestapo claims jurisdiction and orders the Kripo to close its investigation, but March continues to investigate. When the SS and Gestapo try to force him to shut down his investigation, March is only saved by the personal intervention of Kripo Chief Arthur Nebe, who instructs him to continue investigating with only his limited protection. Nebe, a veteran of the pre-Nazi period, suggests that he is engaged in a power struggle against Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the SS, a potential successor to the elderly Hitler.

March meets with Charlotte 'Charlie' Maguire, an American journalist of German descent, who was secretly contacted by one of the victims, Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart, and discovered his body. Maguire tells March that Stuckart had wanted to defect to the United States and claimed to possess important information that would help his case. Both are determined to investigate further and follow the trail of Bühler, Stuckart and a missing former diplomat named Martin Luther to Zürich to investigate a private Swiss bank account they set up. They find no papers but only stolen treasure and return empty handed. Upon their return to Berlin, March eventually discovers that several documents related to all victims have been removed from the Reich archives, but that an initial invitation for a political conference centered around 'resolving' the Jewish question in 1941 was overlooked by the Gestapo. Luther eventually reaches out to Maguire in the same way Stuckart did, but when March and Magurie try to reclaim him, he is shot by a sniper.

Nevertheless, March determines that Luther hid the documents he had taken from Zurich at the airport before disappearing. Recovering them, March and Maguire discover the truth: in 1942, Heydrich has summoned dozens of officals to a conference in Wannsee to plan the Final Solution, the extermination of all the Jews which few Germans are aware other beyond rumours. Since the war ended, Heydrich had secretly started to elimiate the attendees, though so infrequently that no suspicion could be elicited. The elimination was hurried however due to an upcoming meeting of Hitler and US President Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., by ensuring that the fate of the missing Jews can never be revealed. Nebe reveals to March that Germany needs the Americans to stop supporting the Soviet guerillas in the east due to the abject failure of Hitler's 'Lebensraum' policy. With German colonists desperate to return to Germany to escape the constant war and harsh economic conditions, the Nazis are trying to prevent a human, economic and political catastrophe. Bühler, Stuckart and Luther had realised in 1942 that Heydrich's refusal to produce a signed order from Hitler authorising the Final Solution was meant to shield him politically and let them take the blame if needed. As a result, they hid all the documents they could find to cover themselves before Heydrich targeted them for elimination.

Armed with the documents, but unable to use offical diplomatic channels which would be dominated by Kennedy officials desperate to achieve détente with Germany, Maguire heads for Switzerland and hopes to expose the evidence of the extermination to the world. March plans to join her, but first goes to see his estranged ten-year-old son, who denounces him to the Gestapo. In the cellars of Gestapo headquarters at Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, March is tortured but does not reveal Maguire's location, aware that the longer he holds out is the more time she has to get away with the story. Odilo Globocnik, Heydrich's right-hand man who had been responsible for the assassinations, boasts that Auschwitz and the other camps have been totally razed and that March will never know the truth for certain. Nebe stages a rescue with the intention of tracking March as he meets with Maguire at their rendezvous. Realising what is happening, March heads for Auschwitz to lead the authorities in the wrong direction.

The Gestapo catches up with March at the unmarked site of the camp near Auschwitz. Knowing that Maguire had enough time to cross the border into Switzerland, March searches for some sign that the camp existed. As Gestapo agents close in on him in a helicopter, March uncovers bricks in the undergrowth. Satisfied, he pulls out his gun and continues to walk towards the birch woods.

Characters

[edit]Fictional

[edit]- Xavier March: A detective in the Kriminalpolizei with the concurrent honorary rank of Sturmbannführer (Major) in the SS, March (nicknamed "Zavi"- although his name, Xavier, begins with an 'x'- by his friends) is a 42-year-old divorcé living in Berlin. He has one son, Pili (Paul), who lives with March's ex-wife, Klara. March commanded a U-boat[note 2] in World War II and was decorated for bravery and promoted. He married his nurse after the war, but the marriage steadily deteriorated afterward. His military service helped him rise through the police ranks to detective. By 1964, however, he is secretly under Gestapo surveillance since it correctly perceives him to have an intense dislike of the Nazi regime. For example, March refuses to donate to the 'winter-relief', shows "insufficient enthusiasm" for his son's involvement in the Jungvolk, has rebuffed all incentives to join the Nazi Party, tells "jokes about the Party" and, worst of all, has shown some curiosity about what happened to a Jewish family that used to live in his present apartment.

- Charlotte "Charlie" Maguire: A 25-year-old American journalist, Maguire has been assigned to Berlin by the fictional news service World European Features. Midway through the novel, she and March fall in love and begin a relationship. Maguire comes from a prominent Irish-American political family but is something of a renegade. The daughter of a US State Department official and German actress who left with him before the war, Maguire speaks fluent German without an accent.[2]

- Hermann Jost: A 19-year-old cadet in an SS academy[note 3], Jost was out running when he discovered the corpse that triggered March's investigation. March is certain that Jost witnessed more than he is willing to disclose and at first believes him to be covering up a homosexual relationship with a fellow cadet, which (in Germany) is punishable by internment in a concentration camp. March, however, persuades Jost to admit the truth: Jost witnessed the dumping of the body and recognized SS General Odilo Globocnik at the scene. To deny March his key witness, Globocnik arranges Jost's transfer 'east'[note 4] for 'special training'.

- Paul "Pili" March: The ten-year-old son of March, Pili lives with his mother and her partner in the suburbs of Berlin. Pili is a fully-indoctrinated member of the Jungvolk, the junior section of the Hitler Youth for boys between 10 and 14. Later in the novel, Pili denounces his father to the Gestapo, all the while unaware of what it will really do to him.

- Max Jaeger: March's friend and Kripo partner, Jaeger is 50; lives with his wife, Hannelore, and four daughters in Berlin; and is disinclined to question 'the system'. At the end of the novel, he drives the getaway car that rescues March, but it is revealed that he had been informing against March since before the novel began and that March's "rescue" was arranged by the Gestapo as a ruse to find Maguire.

- Walther Fiebes: A detective working in VB3, the Kripo's sexual crimes division, along the corridor from March's office, Fiebes is a man with a deeply prurient nature and relishes his work investigating sexual crimes, including rape, adultery and interracial relationships between "Aryan" people and their Slavic servants.

- Rudolf "Rudi" Halder: March's friend and a crewman on his U-boat, Rudi is now a historian working at the immense Reich Central Archives and helping to compile an official history of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS on the Eastern Front.

- Karl Krebs: An officer in the Gestapo, Krebs is an example of the younger, university-trained SS-men hated by Globocnik.

Based on historical figures

[edit]Harris, in the Author's notes of the novel, explains that many characters are based on the real people with the same names and that the biographical details are accurate until 1942. Afterward, the narrative is fictional.[1] The following descriptions follow what is in the novel.

- Odilo Globocnik: An aging Obergruppenführer in the Gestapo and right-hand man of Reichsführer-SS Reinhard Heydrich, nicknamed "Globus". He is a principal antagonist of the book who is personally responsible for the assassinations of the Wannsee officials. After March's apprehension by the Gestapo, Globus takes over March's interrogation and administers several brutal beatings.

- Arthur Nebe: The chief of the Kripo and Oberstgruppenführer, Nebe is an old man in 1964 and has a sumptuous office in Berlin.[3] Initially appearing to support March's investigation for political reasons, despite the Gestapo's involvement, Nebe ultimately weaves a ruse to March to make him reveal the whereabouts of the evidence after meeting with Heydrich several times.

- Josef Bühler: A former secretary and deputy governor to the Nazi-controlled General Government in Kraków, retired in 1951 after losing his leg in a partisan attack.[4] The discovery of his dead body is the starting point of the novel.

- Wilhelm Stuckart: A Nazi Party lawyer, official and retired state secretary in the German Interior Ministry. At the beginning of the novel he has already died the day before Bühler.

- Martin Luther: An advisor to Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop until retirement, and last surviving participant of the Wannsee Conference.

- Reinhard Heydrich: The current head of the SS and considered a likely successor to Hitler, Heydrich is a principal antagonist of the book although he never appears in person. He ordered the assassinations of the Wannsee officials to eradicate all first-hand evidence of the Final Solution.

Others mentioned

[edit]In each case, the description after the name describes how the characters appear in the novel, again by following reality until 1942.[1]

- Adolf Hitler: The elderly and increasingly-reclusive Führer of the Greater German Reich, since the end of the war, Hitler has toned down his image by eschewing his uniform in favour of civilian clothing. His speeches are now at a rate that is calm, rather than furious.

- Heinrich Himmler: Dying in a plane crash in 1962, Himmler was succeeded as Reichsführer-SS by Heydrich.[5]

- Hermann Göring: Died in 1951, years before the book storyline, of an undisclosed illness.[5] Berlin's international airport is named after him, and his estate of Carinhall is a museum.

- Joseph Goebbels: still alive in 1964 and remaining Minister of Propaganda.

- Hanna Reitsch: Germany's leading aviatrix. A statue of her made of melted-down Spitfire and Lancaster aircraft stands in front of Berlin's international airport.

- Winston Churchill: The former British Prime Minister, Churchill fled the country upon Britain's peace agreement with the Reich and now lives in Canada.[6]

- Elizabeth II: Living in Canada like Winston Churchill, she claims the throne from her uncle.

- Edward VIII: Originally reigned as the King of the United Kingdom until his abdication in 1936. He was reinstalled as King (with his wife, Wallis Simpson, becoming Queen) following the Axis victory in Europe.[7]

- Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.: The President of the United States, he is mentioned as standing for re-election and preparing to visit Berlin on a state visit in September[note 5].

- The Beatles are also referenced, though not by name. Their recent appearances in Hamburg and their great popularity with young Germans have been condemned in the German press.[7]

The people in the book who are named as attending the Wannsee Conference all did so in real life. Some are central to the plot, but the others had already died before the events of the novel.[1]

Backstory

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Alternative World War II history

[edit]

Throughout the novel, Harris gradually explains, in a fictional backstory, the developments that allowed Germany to prevail in World War II. The author explains in the Author's notes that except for the backstories of the fictitious characters, the narrative describes reality up to 1942, after which it is fictional.[1] A significant early point of divergence is that Heydrich survived the assassination attempt by Czechoslovak fighters in May 1942 (he was killed in reality) and later became head of the SS. The Nazi offensives on the Eastern Front ultimately pushed back the Soviet forces, with the Case Blue operation succeeding in capturing the Caucasus and cutting the Red Army off from its petroleum reserves by 1943.[6] The Nazis also found that the Enigma machine code had been broken, recalling the entire U-boat fleet for a time to discontinue its use. A subsequent massive U-boat campaign against Britain then succeeded in starving the British into surrender by 1944.[6]

In the novel Princess Elizabeth and the Prime Minister Winston Churchill fled into exile in Canada.[6] Elizabeth now claims the throne from her uncle Edward VIII, who regained the British throne soon afterwards, with Wallis Simpson as his queen.[8][7][6] The US defeated Japan and used nuclear weapons, as in real life.[6] Germany in return fired a non-nuclear "V-3" missile to explode in the skies over New York City to demonstrate its ability to attack the Continental United States with long-range missiles.[6] Thus, after a peace treaty in 1946, the US and Germany are the novel's two superpower opponents in a Cold War.[note 6][6]

There is a reference to a brutal regime having taken power in China, though its ideology and leader are never stated.

Alternative postwar history

[edit]The fictional backstory describes how, after victory is achieved, Germany reorganises Europe east of Poland into Reichskommissariats. After the Treaty of Rome is signed, both Western Europe and Northern Europe are corralled into a trade bloc, the European Community (EC)[note 7]. By 1964, the United States and the Greater German Reich are involved in a Cold War.[6]

The action of the novel takes place from 14 to 20 April 1964, as Germany prepares for Hitler's 75th birthday celebrations, which are to take place on the latter date. A visit by US President Joseph P. Kennedy is planned as part of a gradual détente between the United States and Germany. The Holocaust has been officially explained away as merely the relocation of the Jews 'east', where infrastructure and communications remain far more primitive than in central Europe.

Many in 1960s Germany suspect the government to have eliminated the Jews, but are generally too unconcerned about the event or too afraid of the authorities to say or to do anything. The outside world is aware of the Holocaust, but some doubt has been sown thanks to educated German diplomats offering various explanations for any proof or witnesses that have escaped German territory. Kennedy, however, remains neutral to avoid further damaging relations and refers only to vague "human rights violations" that he wishes to investigate when he visits Berlin.

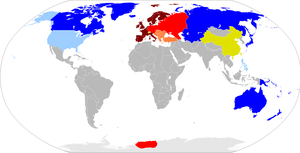

Greater German Reich and international politics

[edit]

The first few pages of the novel feature two maps: one of the city centre of Berlin and another of the extent of the massively expanded Greater German Reich, which stretches from Alsace-Lorraine ("Westmark") in the west to the Ural Mountains and lower Caucasus in the east, with specific locations mentioned in the novel marked.[9]

The Reich has retained Austria (now called "Ostmark"), Slovenia, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Luxembourg (now called "Moselland"). In the east, most of Poland is still ruled as a colony as the General Government, and the former Soviet territories west of the Urals have been divided into four Reichkommissariats:

- Ostland (Belarus and the Baltic states)

- Ukraine, including Odessa, the Generalkommissariat Taurida (Southern Ukraine) and the Crimea, now called Gotenland

- Muscovy (from Moscow to the Urals)

- Caucasus.

Also mentioned is a German naval base in Trondheim, Norway, where the Reich's nuclear submarines are based.[7] Berlin is a city with a population of ten million inhabitants. It is the largest city in the German Reich and the capital of Germany and has been extensively redeveloped by Albert Speer.

A greatly reduced Soviet rump state— presumably composed of Siberia, the Russian Far East and Central Asia—still exists, with its capital in Omsk. The US covertly supplies it with weapons and funds, which allow the Soviets to tie down German forces in the Urals. Although German propaganda plays down the war on the Eastern Front, the war there is taking its toll.

The countries of western and northern Europe have formed the European Community (EC), a pro-German economic bloc with its parliament located in Berlin. It is made up of Portugal, Spain, France, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland. The EC countries, despite being nominally free nations under their own governments and leaders, are politically subordinate to Germany in all but name. This is symbolized by the German flag flown over the Berlin headquarters being twice as large as those of the other member states. The Balkan states remain independent outside of the EC, but are still subject to German diktats. These include Croatia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and Serbia.

The Reich had initially planned to annex Switzerland, but because of Cold War tensions, Switzerland became a convenient neutral spot for diplomacy and for American and German intelligence agents to spy on each other. It is one of the last states in Europe with a foreign policy that is independent of Berlin.

The United States is locked in a Cold War with Germany. Since the end of WWII, both superpowers have developed nuclear and space technologies. The United States is said not to have participated in the Olympic Games since 1936, but is expected to return in 1964. The stalemate between Germany and the United States seems to overshadow international relations. New German buildings are constructed with mandatory bomb shelters, and the Reichsarchiv claims to have been built to withstand a direct missile hit.[10][11]

Nazi society

[edit]German foreign policy concentrates on ending the Cold War. Hitler has taken some steps to soften his image over the years and now usually wears civilian clothes, instead of the party uniform. Nonetheless, no substantive changes have taken place in the regime's basic character. The Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act of 1933, the legal basis for Hitler's dictatorship, remain in effect, and the press, radio and television are all tightly controlled.

The bedrock of Nazi ideology is still the policy of blaming subversive and minority groups for Germany's economic and social problems. Christianity is still permitted in the German Reich, but the Gestapo keeps record of all who attend church services. Homosexuals are sent to labour camps, and Judaism is totally eradicated. Propaganda has previously depicted the United States to be corrupt, degenerate and poor. However, the imminent diplomatic meeting between Hitler and Kennedy forces German propaganda to shift to a more positive image of the United States and its people.

Despite its ideological and moral decline, Germany maintains a high standard of living, having built an empire at the expense of the rest of Europe. European satellite states export high-quality consumer goods to Germany (noted imports are domestic electronics from Britain) and also provide services, such as an SS academy in Oxford and imported domestic staff. Hitler's personal tastes in art and music remain the norm for German society.

Military service remains compulsory, as Germany is still at war with a rump Soviet Union east of the Urals.[12] As the first generation of Nazi leaders who founded the party and came to power alongside Hitler begins to die off, Nazi officials are increasingly well-educated technocrats in the mould of Albert Speer. The police force (the Orpo, or uniformed police, and the Kripo, or criminal investigation bureau) is integrated with the SS, with police officers having honorary SS ranks.[note 8]

According to the main characters, however, German society in the early 1960s is becoming more and more rebellious. The younger generation has no memory of the instability that paved the way for Hitler's rise to power. American and British cultural influence and growing pacifism have taken hold among German youth. Jazz music is still popular, and the German government claims to have come up with a version which is free from "Negroid influence". In spite of the general repression, the Beatles' real-life Hamburg engagements occur in the novel and have already been denounced in the state-controlled press.[7] Germany is periodically attacked by resistance terrorists, with officials assassinated and civilian airliners bombed in-flight. Universities are centres of student dissent, with opposition movements such as the White Rose being once again active.

Nazi organisations such as Kraft durch Freude still exist and fulfill their original roles such as providing holidays to resort areas under German control. German citizens are still encouraged to contribute to the Winterhilfswerk. A sprawling transport network covers the entire Reich, including a vast autobahn and railway network in the manner of the real-life proposed Breitspurbahn system, which carries immense trains.

Technology

[edit]The level of technology in the novel's 1960s is much the same as in real life. The German military uses jet aircraft, nuclear submarines,[7] and aircraft carriers; civilian technology has also advanced considerably. Jet airliners,[13] televisions,[14] coffee machines and photocopiers[15] are used in Germany. The use of photocopiers is restricted to track their use in case they are utilized by dissidents.

Both the United States and Germany appear to have sophisticated space technology. Germany's space program is based at the old rocket-testing facility at Peenemünde, on the Baltic coast. The extent of space exploration is not specified, but a conversation between March and Maguire suggests that Germany is justified in boasting about being ahead of the US in the Space Race.[16]

Critical evaluations

[edit]The British scholar Nancy Browne noted the similarities between the ending of Fatherland and that of Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls: "Both novels end with the protagonist about to embark on a single-handed armed confrontation with a large number of Fascists or Nazis, of whose outcome there can be no doubt - but the reader does not witness the moment of his presumed death.... Like Hemingway's Robert Jordan, Xavier March is facing this last moment with an exhilaration born of having no further doubts and dilemmas, no more crucial decisions which need to be made, nothing but going through on his chosen course and dying in a just cause. And like Jordan, in sacrificing himself March is ensuring the safe escape of the woman he loves".[17]

The review by The Guardian, written by John Mullan, noted that Harris had acknowledged a debt to Len Deighton's SS-GB (1978), an earlier postwar alternative or "counter-factual" history, which was set in Great Britain in late 1941 after the (fictional) British surrender.[18] Part 2 of the review stated that Harris's "invention of a nightmarish alternative history is... compelling".[19]

In other media

[edit]Film

[edit]A TV film of the book was made in 1994 by HBO, starring Rutger Hauer as March and Miranda Richardson as Maguire for which she received a Golden Globe Award in 1995 for Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Series, Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for TV. Rutger Hauer's performance was also nominated, as well as the film itself. The film also received an Emmy nomination in 1995 for Special Visual Effects.[20]

In January 2009 German movie company UFA planned another film adaption of the novel.[21] By March 2012, Dennis Gansel and Matthias Pachte had teamed up to write the screenplay, with Gansel as a candidate for director.[22]

Radio

[edit]The novel was serialised on BBC radio, starring Anton Lesser as March and Angeline Ball as Charlie Maguire. It was dramatised, produced and directed by John Dryden and was first broadcast on 9 July 1997. The ending is changed slightly to allow for the limitations of the medium: the entire Auschwitz camp is discovered in an abandoned state, and Maguire's passage into Switzerland is confirmed to have occurred.

Audiobook

[edit]The unabridged audiobook version of the novel was released by Random House Audio in 1993, read by Werner Klemperer, a refugee from Nazi Germany [citation needed] who is best remembered for his two-time Emmy Award-winning role of bumbling Colonel Klink on the 1960s TV series Hogan's Heroes.

Release details

[edit]- 1992, UK, Hutchinson (ISBN 0-09-174827-5), Pub date 7 May 1992, hardback (First edition)

- 1992, USA, Random House (ISBN 0-679-41273-5), Pub date June 1992, hardback (First USA edition)

- 1993, UK, Arrow (ISBN 0-09-926381-5), Pub date 12 May 1993, paperback

- 2012, 20th Anniversary edition, UK, Arrow (ISBN 978-0-09-957157-5), Pub date 26 April 2012, paperback

The novel is in seven parts, each consisting of several chapters. The first six parts describe the fictitious events of Tuesday, 14 April, to Sunday, 19 April 1964, and are named after the individual days. The last part, Führertag is set on Hitler's 75th birthday, on Monday, 20 April 1964.[23]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As with the other "real" characters in the novel, he is described factually until 1942, when its treatment of him becomes fictional.[1]

- ^ The novel names the real U-174 as the boat March commanded.

- ^ The academy in the novel is named after real life SS commander Sepp Dietrich. Sepp Dietrich commanded the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler for most of the war. Jost's father was a founding member of the Leibstandarte.

- ^ The extermination of the Jews in the novel is also referred to as sending them 'east', suggesting Jost was killed.

- ^ The 1964 United States presidential election was held in November.

- ^ It is not explicitly stated in the novel whether Germany and the US are the only nuclear powers in the world.

- ^ A proposed European Confederation was ultimately rejected in reality by Hitler.

- ^ The real-life integration occurred in 1936.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Harris (2000), pp. 385–386; Author's Note

- ^ Harris (2000), pp. 206–207; Part 3, chapter 7

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 138; Part 3, chapter 2

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 51-52; Part 2, chapter 1

- ^ a b Harris (2000), p. 86; Part 2, chapter 5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harris (2000), p. 85; Part 2, chapter 5

- ^ a b c d e f Harris (2000), p. 40; Part 1, chapter 4

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 5; Part 1, chapter 1

- ^ Harris (2000), Introduction.

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 112; Part 2, chapter 7

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 244; Part 4, chapter 3

- ^ Harris (2000), p. ?; Part 3, chapter 3

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 26; Part 1, chapter 3

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 168; Part 3, chapter 3

- ^ Harris (2000), pp. 251–252; Part 4, chapter 4

- ^ Harris (2000), p. 209; Part 3, chapter 7

- ^ "Dr. Nancy Browne, "In the perspective of a half a century after the event: Anti-Fascist and Anti-Nazi Resistance in English-language Popular Culture" in Tamara Baxter (ed.) "Multi-Disciplinary Round Table on the Lasting Heritage of the Twentieth Century"

- ^ Mullan, John (30 March 2012). "Fatherland by Robert Harris – Week one: speculative fiction". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Mullan, John (6 April 2012). "Fatherland by Robert Harris – Week two: discoveries". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "47th Emmy Awards Nominees and Winners: outstanding individual achievement in special visual effects - 1995". Emmys. Television Academy. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Blasina, Niki (16 January 2009). "UFA adopts 'Fatherland' project". Variety. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (7 March 2012). "UFA moves ahead with Fatherland adaptation | News | Screen". Screendaily.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ Harris (2000), pp. 1–386.

Works cited

[edit]- Harris, Robert (2000). Archangel; Fatherland. Cresset Editions. ISBN 0-09187-209-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Although this cited edition is an omnibus volume of two novels, the page numbering is apparently the same as in the earlier single editions. The 2012 edition is numbered differently.

External links

[edit]- Fatherland (1994 film) at IMDb

- Fatherland, movie trailer on YouTube

- John Mullan, Fatherland by Robert Harris, The Guardian, 30 March 2012

- Graeme Shimmin, Fatherland by Robert Harris: Book Review

- Evelyn Robinson, Review: Fatherland by Robert Harris, Alternate History Weekly Update, 20 November 2012

- Fatherland title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Fatherland at the Internet Book List

- 1992 British novels

- Dystopian novels

- British novels adapted into films

- Alternate Nazi Germany novels

- Novels by Robert Harris

- 1992 science fiction novels

- British thriller novels

- British detective novels

- Fiction set in 1964

- Novels set in the 1960s

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Detective novels

- English novels

- Hutchinson (publisher) books

- Novels set in Berlin

- Crime and thriller fiction set in alternate histories

- Cultural depictions of George VI

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth II

- Cultural depictions of Winston Churchill

- Cultural depictions of Adolf Hitler

- Cultural depictions of Joseph Goebbels

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- Cultural depictions of Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson