White Latin Americans

Eurolatinoamericanos | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 191.5 million – 220.6 million[1][2] 40.0% of Latin American population

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 88M[3] | |

| 18M–59M (52M)[4][5][6] | |

| 38M[2] | |

| 8.4M–13M (10.7M)[2][7] | |

| 12M[2] | |

| 4.1M–13M (8.55M)[2][8][9] | |

| 7.1M[10] | |

| 3.3M[2] | |

| 2.9M[11] | |

| 1.1M–2.1M (1.6M)[12] | |

| 1.6M[13] | |

| 1.3M[14] | |

| 1.2M[2] | |

| 0.812M[15] | |

| 0.71M[2][16] | |

| 0.56M[17] | |

| 0.455M[2] | |

| 0.37M[18][19] | |

| 0.366M[20] | |

| 0.09M[21] | |

| Languages | |

| Major languages Spanish and Portuguese Minor languages Italian, French, English, German, Dutch, and other languages[22] | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (mainly Roman Catholicism, with minority Protestantism),[23] Minority: Judaism[citation needed] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mestizos, Mulattoes, Spaniards, Portuguese, other European peoples[citation needed] | |

White Latin Americans or European Latin Americans (sometimes Euro-Latinos[24][25]) are Latin Americans who claim or being classified as white people with predominant European ancestry.[26]

Theoretically, notable or direct descendants of European settlers who arrived in the Americas during the colonial and post-colonial periods can be found throughout Latin America. Most immigrants who settled the region for the past five centuries were Spanish and Portuguese; after independence, the most numerous non-Iberian immigrants were French, Italians, and Germans, followed by other Europeans as well as West Asians (such as Levantine Arabs and Armenians).[27][28][29]

Composing from 33% of the population as of 2010[update], according to some sources,[1][2][30] White Latin Americans constitute the second largest racial-ethnic group after mestizo people (Amerindian and European mixed) in the region. Latin American countries have often tolerated interracial marriage since the beginning of the colonial period.[31][32] White (Spanish: blanco or güero; Portuguese: branco) is the self-identification of many Latin Americans in some national censuses. According to a survey conducted by Cohesión Social in Latin America, conducted on a sample of 10,000 people from seven countries of the region, 34% of those interviewed identified themselves as white.[33]

Being white

[edit]Being white is a term that emerged from a tradition of racial classification that developed as many Europeans colonized large parts of the world and employed classificatory systems to distinguish themselves from the local inhabitants. However, while most present-day racial classifications include a concept of being white that is ideologically connected to European heritage and specific phenotypic and biological features associated with European heritage, there are differences in how people are classified. These differences arise from the various historical processes and social contexts in which a given racial classification is used. As Latin America is characterized by differing histories and social contexts, there is also variance in the perception of whiteness throughout Latin America.[34]

According to Peter Wade, a specialist in race concepts of Latin America,

...racial categories and racial ideologies are not simply those that elaborate social constructions on the basis of phenotypical variation or ideas about innate difference but those that do so using the particular aspects of phenotypical variation that were worked into vital signifiers of difference during European colonial encounters with others.[35]

In many parts of Latin America, being white is more a matter of socio-economic status than specific phenotypic traits, and it is often said that in Latin America "money whitens".[36] Within Latin America there are variations in how racial boundaries have been defined. In Argentina, for example, the notion of mixture has been downplayed. Alternately, in countries like Mexico and Brazil mixture has been emphasized as fundamental for nation-building, resulting in a large group of bi-racial mestizos, in Mexico, or tri-racial pardos, in Brazil,[37][38] who are considered neither fully white nor fully non-white.[39]

Unlike in the United States (where ancestry may be used exclusively to define race), by the 1970s, Latin American scholars came to agree that race in Latin America could not be understood as the "genetic composition of individuals" but instead must be "based upon a combination of cultural, social, and somatic considerations". In Latin America, a person's ancestry may not be decisive in racial classification. For example, full-blooded siblings can often be classified as belonging to different races (Harris 1964).[40][41]

For these reasons, the distinction between "white" and "mixed", and between "mixed" and "black" and "indigenous", is largely subjective and situational, meaning that any attempt to classify by discrete racial categories is fraught with problems.[42]

History

[edit]

People of European origin began to arrive in the Americas in the 15th century since the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Most early migrants were male, but by the early and mid-16th century, more and more women also began to arrive from Europe.[43]

After the Wars of Independence, the elites of most of the countries of the region concluded that their underdevelopment was caused by their populations being mostly Amerindian, Mestizo or Mulatto;[44] so a major process of "whitening" was required, or at least desirable.[45][46] Most Latin American countries then implemented blanqueamiento policies to promote European immigration, and some were quite successful, especially Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, the number of European immigrants who arrived far surpassed the number of original colonists. Between 1821 and 1932, of a total 15 million immigrants who arrived in Latin America,[27] Argentina received 6.4 million, and Brazil 5.5 million.[47]

Historical demographic growth

[edit]The following table shows estimates (in thousands) of white, black/mulatto, Amerindian, and mestizo populations of Latin America, from the 17th to the 20th centuries. The figures shown are, for the years between 1650 and 1980, from the Arias' The Cry of My People...,[48] for 2000, from Lizcano's Composición Étnica....[2] Percentages are by the editor.

| Year | White | Black | Amerindian | Mestizo | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1650 | 138 | 67 | 12,000 | 670 | 12,875 |

| Percentages | 1.1% | 0.5% | 93.2% | 5.2% | 100% |

| 1825 | 4,350 | 4,100 | 8,000 | 6,200 | 22,650 |

| Percentages | 19.2% | 18.1% | 35.3% | 27.3% | 100% |

| 1950 | 72,000 | 13,729 | 14,000 | 61,000 | 160,729 |

| Percentages | 44.8% | 8.5% | 8.7% | 37.9% | 100% |

| 1980 | 150,000 | 27,000 | 30,000 | 140,000 | 347,000 |

| Percentages | 43.2% | 7.7% | 8.6% | 40.3% | 100% |

| 2000 | 181,296 | 119,055 | 46,434 | 152,380 | 502,784 |

| Percentages | 36.1% | 23.6% | 9.2% | 30.3% | 100% |

Admixture

[edit]

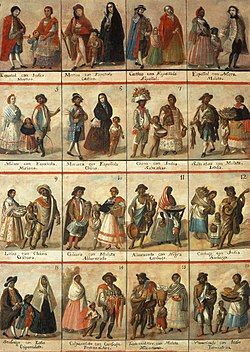

Since European colonization, Latin America's population has had a long history of intermixing. Today, many Latin Americans who have European ancestry, may have varying degrees of Indigenous or Sub-Saharan African ancestry as well. The casta categories used in 18th-century colonial Latin America designated people according to their ethnic or racial background, with the main classifications being indio (used to refer to Native American people), Spaniard, and mestizo, although the categories were rather fluid and inconsistently used. Under this system, those with one Indio great-grandparent but the remainder being Spaniards, were legally Spaniards. The offspring of a castizo and Spaniard was a Spaniard. The same was not true for African ancestry.

As in Spain, persons of Moorish or Jewish ancestry within two generations were generally not allowed to enroll in the Spanish Army or the Catholic Church in the colonies, although this prohibition was inconsistently applied. Applicants to both institutions, and their spouses, had to obtain a Limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) certificate that proved that they had no Jewish or Moorish ancestors, in the same way as those in the Peninsula did. However, being a medieval concept that was more of a religious issue rather than a racial issue, it was never a problem for the native or slave populations in the colonies of the Spanish Empire, and by law people from all races were to join the army, with openly practicing Roman Catholicism being the only prerequisite. One notable example was that of Francisco Menendez, a freed-black military officer of the Spanish Army during the 18th century at the Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose fort in St. Augustine, Florida.[49]

European DNA

[edit]| Country | European DNA average | |

|---|---|---|

| Native European | 99 | |

| Argentina[50] | 71 | |

| Bolivia[51] | 25 | |

| Brazil[52] | 59 | |

| Chile[53] | 54 | |

| Colombia[54] | 42 | |

| Costa Rica[52] | 58 | |

| Cuba[55] | 71 | |

| Ecuador[56] | 36 | |

| El Salvador[57] | 47 | |

| Guatemala[58] | 35 | |

| Haiti[59] | 11 | |

| Honduras[50] | 50 | |

| Mexico[60] | 50 | |

| Nicaragua[50] | 57 | |

| Panama[61] | 25 | |

| Paraguay[62] | 60 | |

| Peru[63] | 26 | |

| Puerto Rico[52] | 64 | |

| Dom. Rep.[64] | 57 | |

| Uruguay[65] | 77 | |

| Venezuela[50] | 56 | |

Self-identified Populations

[edit]The country with the largest number of self-identified Euro-Latino inhabitants in Latin America is Brazil, with 88 million out of 203.0 million total Brazilians,[66] or 43.4% of the total population, as of the 2022 census. Brazil's southern region contains the highest concentration, at 79% of the population self-identificated.[3] Argentina received the largest number of post-colonial European immigrants, with more than 7 million,[67] second only to the United States, which received 24 million.In terms of percentage of the total population, Uruguay has the highest concentrations of self-identified or classified whites, who constitute +70% of their total population, while Honduras and El Salvador have the smallest classified white population, in a range of 1-13%.

| Country | Self-identified (ethnic or skin color) | Classified (cultural perception) |

|---|---|---|

| 54[7] | 85[2] | |

| 5[68] | 15[2] | |

| 44[69][70] | ||

| 46[7] | 53[2] | |

| 23[7] | 21[2] | |

| 34[7] | 83[71][72] | |

| 64[73] | 37[2] | |

| 19[13] | ||

| 2[74] | 10[2] | |

| 13[75][76] | 1[2] | |

| 5[7] | 4[77] | |

| 5[78] | ||

| 8[79] | 1[80][81] | |

| 41[5][6] | 30[4] | |

| 9[82] | 17[83] | |

| 15[7] | 10[84] | |

| 23[7] | 20[2] | |

| 6[85] | 12[2] | |

| 17[17] | ||

| 58[7] | 88[2][86] | |

| 44[8][9] | 17[2] |

European influence by country

[edit]North America

[edit]Mexico

[edit]The European influence in Mexico has its origin on Spanish immigrants who arrived mainly from northern regions of Spain such as Cantabria, Navarra, Asturias, Burgos, Galicia and the Basque Country;[87] in the 19th and 20th century many non-Iberian immigrants arrived to the country aswell, either motivated by economic opportunity (Americans, Canadians, English), government programs (Italians, Irish, Germans) or political motives such as the French during the Second Mexican Empire.[88][89] In the 20th century, international political instability was a key factor to drive immigration to Mexico; in this era Greeks, Armenians, Poles, Russians, Lebanese, Palestinians and Jews,[89] along with many Spanish refugees fleeing the Spanish Civil War, also settled in Mexico[90] whereas in the 21st century, due to Mexico's economic growth, immigration from Europe has increased (mainly France and Spain), people from the United States have arrived as well, nowadays making up more than three-quarters of Mexico's roughly one million legal migrants. In that time, more people from the United States have been added to the population of Mexico than Mexicans to that of the United States, according to government data in both nations.[91]

Mexico's northern and western regions have the highest percentages of European population, according to the American historian Howard F. Cline the majority of Mexicans in these regions have no native admixture or are of predominantly European ancestry.[92] In the north and west of Mexico the indigenous tribes were substantially smaller and unlike those found in central and southern Mexico they were mostly nomadic, therefore remaining isolated from colonial population centers, with hostilities between them and Mexican colonists often taking place.[93] This eventually led the northeast region of the country to become the region with the highest proportion of whites during the Spanish colonial period albeit recent migration waves have been changing its demographic trends.[94]

Estimates of Mexico's white population differ greatly in both, methodology and percentages given, extra-official sources such as the World factbook which use the 1921 census results as the base of their estimations calculate Mexico's White population as only 9%[95] (the results of the 1921 census, however, have been contested by various historians and deemed inaccurate).[96] Other sources suggest higher percentages: Encyclopædia Britannica does not give an exact percentage, but estimates them at about 30% of the population,[4] field surveys that use the presence of blond hair as a reference to classify a Mexican as White found that 23% of the Metropolitan Autonomous University of Mexico institute's population could be classified as such,[97] with a similar methodology, the American Sociological Association obtained a percentage of 18.8% having its higher frequency on the North region (22.3%–23.9%) followed by the Center region (18.4%–21.3%) and the South region (11.9%).[98] Another study made by the University College London in collaboration with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History found that the frequencies of blond hair and light eyes in Mexicans are of 18% and 28% respectively,[99] surveys that use as reference skin color such as those made by Mexico's National Council to Prevent Discrimination and Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography report percentages that go from 27%[100][101] to around 47%.[102][103][104]

A study performed in hospitals of Mexico City suggests that socioeconomic factors influence the frequency of Mongolian spots among newborns, as evidenced by the higher prevalence of 85% in newborns from a public institution, typically associated with lower socioeconomic status, compared to a 33% prevalence in newborns from private hospitals, which generally cater to families with higher socioeconomic status.[105] The Mongolian spot appears with a very high frequency (85-95%) in Native American, and African children, but can be present in some individuals in the Mediterranean populations.[106] The skin lesion reportedly almost always appears on South American[107] and Mexican children who are racially Mestizos,[108] while having a very low frequency (5–10%) in European children.[109] According to the Mexican Social Security Institute (shortened as IMSS) nationwide, around half of Mexican babies have the Mongolian spot.[110]

Caribbeans

[edit]Cuba

[edit]Self-identified white people in Cuba make up 64.1% of the total population, according to the census of 2012,[111][112] with the majority being of Spanish descent. However, after the mass exodus resulting from the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuba's white population diminished. Today, the various records that claim to show the percentage of whites in Cuba are conflicting and uncertain; some reports (usually coming from Cuba) still report a similar-to-pre-1959 number of 65%, and others (usually from outside observers) report 40–45%. Although most white Cubans are of Spanish descent, others may have French, Portuguese, German, Italian, or Russian ancestry.[113] During the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, large waves of Canarians, Catalans, Andalusians, Castilians, and Galicians immigrated to Cuba. Between 1901 and 1958, more than a million Spaniards arrived in Cuba from Spain; many of these and their descendants left after Castro's Communist regime took power. The country also saw Jewish immigrants coming to the country.[114] Historically, Chinese descendants in Cuba were classified as white. Though more recent censuses would add a yellow (or amarilla) racial category before its removal in 21st century census results.[115][116]

An autosomal study from 2014 found the genetic makeup in Cuba to be 72% European, 20% African, and 8% Native American with different proportions depending on the self-reported ancestry (White, Mulatto or Mestizo, and Black). According to this study Whites are on average 86% European, 6.7% African and 7.8% Native American with European ancestry ranging from 65% to 99%. 75% of whites are over 80% European and 50% are over 88% European[117] According to a study in 2011 Whites are on average 5.8% African with African ancestry ranging from 0% to 13%. 75% of whites are under 8% African and 50% are under 5% African.[118] A study from 2009 analysed the genetic structure of the three principal ethnic groups from Havana City (209 individuals), and the contribution of parental populations to its genetic pool. A contribution from Indigenous peoples of the Americas was not detectable in the studied sample.[119]

| Self-reported ancestry | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 86% | 6.7% | 7.8% |

| White (Havana) | 86% | 14% | 0% |

| Mulatto/Mestizo | 50.8% | 45.5% | 3.7% |

| Mulatto/Mestizo (Havana) | 60% | 40% | 0% |

| Black | 29% | 65.5% | 5.5% |

| Black (Havana) | 23% | 77% | 0% |

Dominican Republic

[edit]The 1750 estimates show that there were 30,863 whites, or 43.7% out of a total population of 70,625, in the colony of Santo Domingo.[120][121] other estimates include 1790 with 40,000 or 32% of the population,[122][123] and in 1846 with 80,000 or 48.5% of the population.[124]

The first census of 1920 reported that 24.9% identified as white. The second census, taken in 1935, covered race, religion, literacy, nationality, labor force, and urban–rural residence.[125] The 2022 census reported that 1,611,752 or 18.7% of Dominicans 12 years old and above self identify as white.[13] This was the first census since 1960 to gather data on ethnic-racial identification.[126]

| Identifying as white 1920-2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % | Ref(s) | |

| 1920 | 223,144 | 24.9 | [127] | |

| 1935 | 192,732 | 13.0 | [128][129] | |

| 1950 | 600,994 | 28.14 | [127] | |

| 1960 | 489,580 | 16.1 | [130][131] | |

| 2022 | 1,611,752 | 18.7 | [13] | |

White Dominicans were estimated to be 17.8% of the Dominican Republic's population, according to a 2021 survey by the United Nations Population Fund.[132] with the vast majority being of Spanish descent. Notable other ancestries includes French, Italian, Lebanese, German, and Portuguese.[133][134][135]

The government of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo made a point of increasing the white population, or "whitening" the racial composition of the country, by rejecting black immigrants from Haiti and local blacks as foreigners.[136] He also welcomed Jewish refugees in 1938 and Spanish farmers in the 1950s as part of this plan.[137][138] The country's German minority is the largest in the Caribbean.[139]

Haiti

[edit]The white and the mulatto population of Haiti are classified about 5% of its population, while 95% is classified being African descent.[78]

That 5% minority group comprises people of many different ethnic and national backgrounds, who are French, Spanish, Polish and other European ancestry,[140][141] as well as the Jewish diaspora, arriving from the Polish legion and during the Holocaust,[140][142] Germans (18th century and World War I),[143][144] and Italian.

Puerto Rico

[edit]

An early census on the island was conducted by Governor Francisco Manuel de Lando in 1530. An exhaustive 1765 census was taken by Lieutenant General Alexander O'Reilly, which, according to some sources, showed 17,572 whites out of a total population of 44,883.[121][145] The censuses from 1765 to 1887 were taken by the Spanish government who conducted them at irregular intervals. The 1899 census was taken by the United States War Department. Since 1910, Puerto Rico has been included in every decennial census taken by the United States.

| Self identify as white 1765 - 2020 (census) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % | Ref(s) | Year | Population | % | Ref(s) |

| 1765 | 17,572 | - | [146] | 1887 | 474,933 | 59.5 | [147] |

| 1775 | 30,709 | 40.4 | [148] | 1897 | 573,187 | 64.3 | [147] |

| 1787 | 46,756 | 45.5 | [148] | 1899 | 589,426 | 61.8 | [147] |

| 1802 | 78,281 | 48.0 | [147] | 1910 | 732,555 | 65.5 | [149] |

| 1812 | 85,662 | 46.8 | [147] | 1920 | 948,709 | 73.0 | [149] |

| 1820 | 102,432 | 44.4 | [147] | 1930 | 1,146,719 | 74.3 | [149] |

| 1827 | 150,311 | 49.7 | [147] | 1940 | 1,430,744 | 76.5 | [150] |

| 1827 | 150,311 | 49.7 | [147] | 1950 | 1,762,411 | 79.7 | [150] |

| 1836 | 188,869 | 52.9 | [147] | 2000 | 3,064,862 | 80.5 | [151] |

| 1860 | 300,406 | 51.5 | [147] | 2010 | 2,825,100 | 75.8 | [152] |

| 1877 | 411,712 | 56.3 | [147] | 2020 | 560,592 | 17.1 | [153] |

In 2010, Self-identifierd white Puerto Ricans are said to comprise the majority of the island's population, with 75.8% of the population identifying as white.[154] Though in the 2020 U.S. census, this percentage dropped to 17.1%.[17] People of self-identified multiracial descent are now the largest demographic in the country, at 49.8%.[17]

In 1899, one year after the U.S invaded and took control of the island, 61.8% identified as white. In 2000, for the first time in fifty years, the census asked people to define their race and found the percentage of whites had risen to 80.5% (3,064,862); not because there has been an influx of whites to the island (or an exodus of non-White people), but a change of race perceptions, mainly because Puerto Rican elites wished to portray Puerto Rico as the "white island of the Antilles", partly as a response to scientific racism.[155][156]

Geologist Robert T. Hill published a book titled Cuba and Porto Rico, with the other islands of the West Indies (1899), wrote that the island was "notable among the West Indian group for the reason that its preponderant population is of the white race"[157] and "Porto Rico, at least, has not become Africanized".[158][159]

According to a genetic research by the University of Brasília, Puerto Rican genetic admixture consists in a 60.3% European, 26.4% African, and 13.2% Amerindian ancestry.[160]

Central America

[edit]Costa Rica

[edit]

From the late 19th century to when the Panama Canal opened, European migrants used Costa Rica to get across the isthmus of Central America to reach the west coast of the United States (California).

The most recent 2022 Costa Rican census recorded ethnic or racial identity for all groups separately for the first time in more than ninety-five years since the 1927 census. Options included indigenous, Black or Afro-descendant, Mulatto, Chinese, Mestizo, white and other on section IV: question 7.[161]

Estimates of the percentage classified as white people vary between 77%[71] and 82%,[2] or about 3.1–3.5 million people. The white and mestizo populations combined equal 83%, according to the CIA World Factbook.[162]

Many of the first Spanish colonists in Costa Rica may have been Jewish converts to Christianity.[163] The first sizable group of self-identified Jews immigrated from diaspora communities in Poland, beginning in 1929. From the 1930s to the early 1950s, journalistic and official anti-Semitic campaigns fueled harassment of Jews; however, by the 1950s and 1960s, the immigrants won greater acceptance. Most of the 3,500 Costa Rican Jews today are not highly observant, but they remain largely endogamous.[164]

A study done in Costa Rica, in the province of Guanacaste, revealed that the average genetic admixture was 45% European, 33% indigenous, 14.6% black and 5.8% Asian.[165]

El Salvador

[edit]

According to the official 2007 Census in El Salvador, 12.7% of Salvadorans identified as being "white",[166] and 86.3% as mestizo.[167]

Before the conquest it was the Central American nation with the lowest Amerindian population,[168] due to diseases and hostility from Europeans, the Amerindian population fell precipitously.[169] This was due to the small indigenous population in the area and colonial governors wanting to repopulate the land with Europeans.[170][171] Spaniards, mainly from Galicia and Asturias emigrated to El Salvador. Later, the country would experience other waves of other European immigrants, mainly Italian and Spaniards.[172][173] The immigration of the time had a great demographic impact, since by 1880 there were 480,000 inhabitants in El Salvador, 40 years later in 1920, there were 1.2 million Salvadorans.[174][175] During World War II, El Salvador gave documents to Jews from Hungary, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Switzerland. It is estimated that they were up to 40,000 immigrants,[176][177] and even up to 50,000.[178][179]

Genetic study of the publication Genomic Components in America's demography, in which geneticists from all over the continent and Japan participated, that the average genetic composition of the average Salvadoran is: 52% European, 40% Amerindian, 6% African and 2% Middle Eastern.[180]

Guatemala

[edit]

In the recent 2018 Census, those mestizos and whites are included in one category (Ladinos), accounting 56% of population.[181] Into the category Ladino, include part of Amerindians culturally Hispanic along people of mixed heritage, part of mixed Guatemalans could have important European ancestry or being castizo (mixed+white), specially in Metropolitan Areas and the East.

The most common European ancestry in Guatemalans mixed is Spanish descent, but there were German and Italian migration throughout Nineteen and Twenty Century in the country[182]

Honduras

[edit]Honduras contains perhaps one of the smallest percentages of classified whites in Latin America, according some census with only about 3% classified in this group.[183] Another census indicates that only a 7.8% of the total population is white in Honduras.[184] During the 19th century several immigrants from Catalonia, Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe arrived to Honduras. Some of these Europeans were Jews from the Russian Empire, escaping the pogroms.[185]

Of these the majority are people of Spanish descent. There is an important Spanish community mostly located in the city of San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa. There are also people from The Bay Islands who descend from British settlers (either English, Irish, or Scottish). Another large migratory group in Honduras is the Arabs, predominantly Palestinians and to a lesser extent Lebanese.[186] Many of these Levantine Arabs were classified as white in national censuses; around 300,000 Arabs live in Honduras.

However, most Hondurans consider themselves as mestizos, regardless of their ethnic category, which is why it is difficult to determine the actual white population of Honduras.[187] According to Admixture and genetic relationships of Mexican Mestizos regarding Latin American and Caribbean populations based on 13 CODIS-STRs, the genetic composition of most Hondurans is 58.4% European, 36.2% Amerindian, and 5.4% African.[188]

Nicaragua

[edit]According to a 2014 research published in the journal Genetics and Molecular Biology and to a 2010 research published in the journal "Physical Anthropology", European ancestry predominates in majority of Nicaraguans at 69% genetic contribution, followed by Native American ancestry at 20%, and lastly Northwest African ancestry at 11%, making Nicaragua the country with one of the highest proportion of European ancestry in Latin America.[189][16] Non-genetic self-reported data from the CIA World Factbook consider that Nicaragua's population averages phenotypically at 69% Mestizo/Castizo, 17% White, 9% Afro-Latino and 5% Native American.[190] This fluctuates with changes in migration patterns. The population is 58% urban as of 2013[update].[191]

In the 19th century, Nicaragua experienced a wave of immigration, primarily from Western Europe. In particular, families moved to Nicaragua to set up businesses with the money they brought from Europe. They established many agricultural businesses, such as coffee and sugarcane plantations, as well as newspapers, hotels, and banks.[citation needed]

A study called "Genomic Components in America's demography" published in 2017, estimates that the average Nicaraguan is of 58-62% European genetic background, primarily of Spanish (43.63%) but also of German, French, and Italian ancestry; 28% of indigenous American ancestry; and 14% of West African origin.[citation needed]

Panama

[edit]White Panamanians are classified as 6.7% of the population,[192] with those of Spanish ancestry being in the majority. Other ancestries includes Dutch, English, French, German, Swiss, Danish, Irish, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian. There is also a sizable and influential Jewish community.[citation needed]

South America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]

The ancestry of Argentines is mostly European, with both Native American and African contributions. According to a 2006 autosomal DNA study the genetic structure of Argentina would be: 78.0% European, 19.4% Amerindian and 2.5% African. Using other methods it was found that it could be: 80.2% European, 18.1% Amerindian and 1.7% African.[193] A 2010 autosomal DNA study found the Argentine population to average 78.5% European, 17.3% Native American, and 4.2% sub-Saharan African, in which 63.6% of the tested group had at least one ancestor who was Indigenous.[194] A unweighted autosomal DNA study from 2012 found the genetic composition of Argentines to be 65% European, 31% Native American, and 4% African. The study's conclusion was not to achieve a generalized autosomal average of the country, but rather the existence of genetic heterogeneity among differing sample regions.[195] A 2015 study concluded that 90% of Argentinians have a genetic composition different from native Europeans.[196][197][198]

Argentina's National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) does not conduct ethnic/racial censuses; so, no official data exist on the percentage of white Argentines today. White Argentines are dispersed throughout the country, but their greatest concentration is in the east-central region of Pampas, the southern region of Patagonia, the west-central region of Cuyo and in the north-eastern region of Litoral. Their concentration is smaller in the north-western region (mainly in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta), which was the most densely populated region of the country (mainly by Amerindian and Mestizo people) before the wave of immigration of 1857-1940 and was the area where European newcomers settled the least.[199][200] During the last few decades, due to internal migration from these north-western provinces—as well as to immigration from Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay—the percentage of white Argentines in certain areas of Greater Buenos Aires has decreased significantly.[201] According to Seldin M. et al (2011) the genetic composition within 94 individuals from Argentina was 78% european, 19% amerindian and around 3% subsaharian african, those results were using the Bayesian clustering algorithm structure while on the weighted least mean square method was 80% european, 18% amerindian and 2% african. [202][203]

The white population in Argentina is mostly descended from immigrants arriving from Europe between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with a smaller proportion from Spaniards of the colonial period. From 1506 to 1650—according to M. Möner, Peter Muschamp, and Boyd-Bowman—out of a total of 437,669 Spaniards who settled in the American Spanish colonies, between 10,500 and 13,125 Peninsulares settled in the Río de la Plata region.[204] The colonial censuses conducted after the creation of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata showed that the proportion of Spaniards and Criollos was significant in the cities and surrounding countryside, but not so much in the rural areas. The 1778 census of Buenos Aires, ordered by Viceroy Juan José de Vértiz, revealed that, of a total population of 37,130 inhabitants (in both the city and surrounding countryside), the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 25,451, or 68.55% of the total. Another census, carried out in the Corregimiento de Cuyo in 1777, showed that the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 4,491 (or 51.24%) out of a population of 8,765 inhabitants. In Córdoba (city and countryside) the Spanish/Criollo people comprised a 39.36% (about 14,170) of 36,000 inhabitants.[205]

Data provided by Argentina's Dirección Nacional de Migraciones (National Bureau of Migrations) states that the country received a total of 6,611,000 immigrants during the period from 1857 to 1940.[206] The main immigrant group was 2,970,000 Italians (44.9% of the total), who came initially from Piedmont, Veneto, and Lombardy, and later from Campania, Calabria, and Sicily.[207] The second group in importance was Spaniards, some 2,080,000 (31.4% of the total), who were mostly Galicians and Basques, but also Asturians, Cantabrians, Catalans, and Andalucians. In smaller but significant numbers came Frenchmen from Occitania (239,000, 3.6% of the total) and Poles (180,000 – 2.7%). From the Russian Empire came some 177,000 people (2.6%), who were not only ethnic Russians, but also Ukrainians, Belarusians, Volga Germans, Lithuanians, etc. From the Ottoman Empire the contribution was mainly Armenians, Lebanese, and Syrians, some 174,000 in all (2.6%). Then come the immigrants from the German Empire, some 152,000 (2.2%). From the Austro-Hungarian Empire came 111,000 people (1.6%), among them Austríans, Hungarians, Croatians, Bosniaks, Serbs, Ruthenians, and Montenegrins. Roughly 75,000 people came from what was then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with the majority of these being Irish immigrants arriving via "coffin ships" escaping the Great Famine. Other minor groups were the Portuguese (65,000), Slavic peoples from the Balkans (48,000), Swiss (44,000), Belgians (26,000), Danes (18,000), white Americans (12,000), the Dutch (10,000), and the Swedish (7,000). 223,000 came from other countries not listed above. Even colonists from Australia, and Boers from South Africa, can be found in the Argentine immigration records.[citation needed] The city's motto is "Crespo: melting pot, culture of faith and hard work", referring to the Volga Germans, Italians, Spaniards, and other ethnicities that comprise its population.[208]

In the 1910s, when immigration reached its peak, more than 30% of Argentina's population had been born in Europe, and over half of the population of the city of Buenos Aires had been born abroad. According to the 1914 national census, 80% out of a total population of 7,903,662 were people who were either European, or the children and grandchildren of same. Among the remaining 20% (the descendants of the population previous to the immigratory wave), about one third were white. That makes for 86.6%, or about 6.8 million whites residing in Argentina.[209] European immigration continued to account for over half the population growth during the 1920s,[210] and for smaller percentages after World War II, many Europeans migrating to Argentina after the great conflict to escape hunger and destitution. According to Argentine records, 392,603 people from the Old World entered the country in the 1940s. In the following decade, the flow diminished because the Marshall Plan improved Europe's economy, and emigration was not such a necessity; but even then, between 1951 and 1970 another 256,252 Europeans entered Argentina.[211] From the 1960s—when whites were 76.1% of the total—onward, increasing immigration from countries on Argentina's northern border (Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay)[212] significantly increased the process of Mestizaje in certain areas of Argentina, especially Greater Buenos Aires, because those countries have Amerindian and Mestizo majorities.[213][214][215]

In 1992, after the fall of the Communist regimes of the Soviet Union and its allies, the governments of Western Europe were worried about a possible mass exodus from Central Europe and Russia. President Carlos Menem offered to receive part of that emigratory wave in Argentina. On December 19, 1994, Resolution 4632/94 was enacted, allowing "special treatment" for applicants who wished to emigrate from the republics of the ex-Soviet Union. From January 1994 until December 2000, a total 9,399 Central and Eastern Europeans traveled and settled in Argentina. Of the total, 6,720 were Ukrainians (71.5%), 1,598 Russians (17%), 526 Romanians, Bulgarians, Armenians, Georgians, Moldovans, and Poles, and 555 (5.9%) traveled with a Soviet passport.[216] 85% of the newcomers were under age 45 and 51% had tertiary-level education, so most of them integrated quite rapidly into Argentine society, although some had to work for lower wages than expected at the beginning.[217]

Genetic studies of Argentina population:

- Homburguer et al., 2015, PLOS One Genetics: 67% European, 28% Amerindian, 4% African and 1.4% Asian.[218]

- Seldin et al., 2006, American Journal of Physical Anthropology: 78.0% European, 19.4% Amerindian and 2.5% African. Using other methods it was found that it could be: 80.2% European, 18.1% Amerindian and 1.7% African.[193]

- According to Caputo et al., 2021, the study of autosomal DIPs show that the genetic contribution is 77.8% European, 17.9% Amerindian and 4.2% African. The X-DIPs matrilineal show 52.9% European, 39.6% Amerindian and 7.5% African.[219]

- Olivas et al., 2017, Nature: 84,1% European and 12,8% Amerindian.[220]

- Corach et al,. 2010, Annals of Human Genetics: 78.5% European, 17.3% Amerindian, and 4.2% African ancestry.[194]

- Avena et al., 2012, PLOS One: 65% European, 31% Amerindian, and 4% African.[221]

- Buenos Aires Province: 76% European and 24% others.

- South Zone (Chubut Province): 54% European and 46% others.

- Northeast Zone (Misiones, Corrientes, Chaco & Formosa provinces): 54% European and 46% others.

- Northwest Zone (Salta Province): 33% European and 67% others.

- Other studies indicate that the genetic composition between regions would be:[222]

- Central Zone: 81% European, 15% Amerindian and 4% African

- South Zone: 68% European, 28% Amerindian and 4% African

- Northeast Zone: 79% European, 17% Amerindian and 4% African

- Northwest Zone: 55% European, 35% Amerindian and 10% African

- Oliveira, 2008, on Universidade de Brasília: 60% European, 31% Amerindian and 9% African.[160]

- National Geographic: 61% Caucasian (52% European + 9% Middle East/North Africa), 27% Amerindian and 9% African.[223]

Bolivia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

White people in Bolivia are classified as 5% of the nation's population.[68] The white population consists mostly of criollos, which consist of families of unmixed Spanish ancestry descended from the Spanish colonists and Spanish refugees fleeing the 1936–1939 Spanish Civil War.[citation needed] These two groups have constituted much of the aristocracy since independence. Other groups within the white population are Germans, who founded the national airline Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano, as well as Italians, Americans, Basques, Croats, Russians, Polish, English, Irish, and other minorities, many of whose members descend from families that have lived in Bolivia for several generations.[citation needed]

Comparatively, Bolivia experienced far less immigration than its South American neighbors.[citation needed]

Brazil

[edit]

Brazil is one of the few countries in Latin America that includes racial categories in its censuses: Branco (White), Negro (Black), Pardo (Multiracial), Amarelo (Yellow) and Indígena (Amerindian), with categorization being by self-identification. Taking into account the data provided by the last National Household Survey, conducted in 2010, Brazil would possess the most numerous white population in Latin America, given that a 47.7% – 91 million people – of Brazilians self-declared as "Brancos".[3] Comparing this survey with previous censuses, a slow but constant decrease in the percentage of self-identified white Brazilians can be seen: in the 2000 Census it was 53.7%,[225][226] in the 2006 Household Survey it was 49.9%,[227] and in the last, 2008, survey it decreased to the current 48.4%.[228] Some analysts believe that this decrease is evidence that more Brazilians have come to appreciate their mixed ancestry, re-classifying themselves as "Pardos".[229] Furthermore, some demographers estimate that a 9% of the self-declared white Brazilians have a certain degree of African and Amerindian ancestry, which, if the "one-drop rule" were applied, would classify them as "Pardos".[230]

The white Brazilian population is spread throughout the country, but it is concentrated in the four southernmost states, where 79.8% of the population self-identify as white.[227] The states with the highest percentage of white people are Santa Catarina (86.9%), Rio Grande do Sul (82.3%), Paraná (77.2%) and São Paulo (70.4%). Another five states that have significant proportions of whites are Rio de Janeiro (55.8%), Mato Grosso do Sul (51.7%), Espírito Santo (50.4%), Minas Gerais (47.2%) and Goiás (43.6%). São Paulo has the largest population in absolute numbers with 30 million whites.[231]

In the 18th century, an estimated 600,000 Portuguese arrived, including wealthy immigrants, as well as poor peasants, attracted by the Brazil Gold Rush in Minas Gerais.[232] By the time of Brazilian independence, declared by emperor Pedro I in 1822, an estimated 600,000 to 800,000 Europeans had come to Brazil, most of them male settlers from Portugal.[233][234] Rich immigrants who established the first sugarcane plantations in Pernambuco and Bahia, and New Christians and Gypsies fleeing from religious persecution, were among the early settlers.

After independence, Brazil saw several campaigns to attract European immigrants, which were prompted by a policy of Branqueamento (Whitening).[45] During the 19th century, the slave labor force was gradually replaced by European immigrants, especially Italians.[235] This mostly took place after 1850, as a result of the end of the slave trade in the Atlantic Ocean and the growth of coffee plantations in the São Paulo region.[236][237] European immigration was at its peak between the mid-19th and the mid-20th centuries, when nearly five million Europeans immigrated to Brazil, most of them Italians (58.5%), Portuguese (20%), Germans, Spaniards, Poles, Lithuanians, and Ukrainians. Between 1877 and 1903, 1,927,992 immigrants entered Brazil, an average of 71,000 people per year, with the peak year being 1891, when 215,239 Europeans arrived.[235]

After the First World War, the Portuguese once more became the main immigrant group, and Italians fell to third place. Spanish immigrants rose to second place because of the poverty that was affecting millions of rural workers.[238] Germans were fourth place on the list; they arrived especially during the Weimar Republic, due to poverty and unemployment caused by the First World War.[239] The numbers of Europeans of other ethnicities increased; among them were people from Poland, Russia, and Romania, who emigrated in the 1920s, probably because of politic persecution. Other peoples emigrated from the Middle East, especially from what now are Syria and Lebanon.[235] During the period 1821–1932, Brazil received an estimated 4,431,000 European immigrants.[47]

After the end of the Second World War, European immigration diminished significantly, although between 1931 and 1963 1.1 million immigrants entered Brazil, mostly Portuguese.[235] By the mid-1970s, some Portuguese immigrated to Brazil after the independence of Portugal's African colonies—from Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau.[240][241]

Genetic studies

[edit]A 2015 autosomal genetic study, which also analysed data of 25 studies of 38 different Brazilian populations, concluded the following: "European (EUR) ancestry is the major contributor to the genetic background of Brazilians, followed by African (AFR), and Amerindian (AMR) ancestries. The pooled ancestry contributions were 0.62 EUR, 0.21 AFR, and 0.17AMR. The Southern region had a greater EUR contribution (0.77) than other regions. Individuals from the Northeast (NE) region had the highest AFR contribution (0.27) whereas individuals from the North regions had more AMR contribution (0.32)".[242]

| Region[242] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West Region | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast Region | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South Region | 77% | 12% | 11% |

An autosomal study from 2013, of nearly 1,300 samples from all regions of Brazil, found predominantly European ancestry, combined with African and Native American contributions in varying degrees:

Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values up to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population.[243]

According to a genetic study about Brazilians (based upon about 200 samples), on the paternal side, 98% of the white Brazilian Y Chromosome comes from a European male ancestor, only 2% from an African ancestor and there is a complete absence of Amerindian contributions. On the maternal side, 39% have European Mitochondrial DNA, 33% Amerindian and 28% African female ancestry. This, considering the facts that the slave trade was effectively suppressed in 1850, and that the Amerindian population had been reduced to small numbers even earlier, shows that at least 61% of white Brazilians had at least one ancestor living in Brazil before the beginning of the Great Immigration. This analysis, however, only shows a small fraction of a person's ancestry (the Y Chromosome comes from a single male ancestor and the mtDNA from a single female ancestor, while the contributions of the many other ancestors is not specified).[244]

According to another study, those who identified as whites in Rio de Janeiro turned out to have 86.4% European ancestry on average.[245]

Chile

[edit]Various autosomal studies have shown the following admixture in Chile:

- 67.9% European; 32.1% amerindian; (Valenzuela, 1984): Marco de referencia sociogenético para los estudios de salud pública en Chile, fuente: Revista Chilena de Pediatría.[246][247]

- 64.0% European; 35.0% amerindian; (Cruz-Coke, 1994): Genetic epidemiology of single gene defects in Chile, fuente: Universidad de Chile.[248]

- 57.2% European; 38.7% amerindian; 2.5% African; 1.7% Asiatic; (Homburger et al., 2015): Genomic Insights into the Ancestry and Demographic History of South America, fuente: PLOS Genetics.[249]

A 2015 autosomal DNA study found Chile to be 55.16% European, 42.38% Native American and 2.44% African, using LAMP-LD modeling; and 54.38% European, 43.22% Native American, and 2.40% African, using RFMix.[250] An autosomal DNA study from 2014 found the results to be 51.85% (± 5.44%) European, 44.34% (± 3.9%) Native American, and 3.81% (± 0.45%) African.[251][252]

A Chilean researcher in 2015 stated that "there are no Chileans without Amerindian or European ancestry".[253] She also added that the average ancestry was 51% European, 44% Amerindian and 3% African, and that in the upper classes the average Amerindian ancestry was 35.2%.

Studies estimates the white population at 52%,[254] to 70% of the Chilean population.[2] According to genetic research by the University of Brasília, Chilean genetic admixture consists of 51.6% European, 42.1% Amerindian, and 6.3% African ancestry.[160] According to an autosomal genetic study of 2014 carried out among soldiers in the city of Arica, Northern Chile, the European admixture goes from 56.8% in soldiers born in Magallanes to 41.2% for the ones who were born in Tarapacá.[255] According to a study from 2013, conducted by the Candela Project in Northern Chile as well, the genetic admixture of Chile is 52% European, 44% Native American, and 4% African.[256]

According to a study performed in 2014,[257] 37.9% of Chileans self-identified as white, a subsequent DNA tests showed that the average self identifying white was genetically 54% European.

Genotype and phenotype in Chileans vary according to social class. 13% of lower-class Chileans have at least one non-Spanish surname, compared to 72% of those who belong to the upper-middle-class.[258] Phenotypically, only 9.6% of lower-class girls have light-colored eyes—either green or blue—where 31.6% of upper-middle-class girls have such eyes.[258] Blonde hair is present in 2.2% and 21.3%, of lower-class and upper-middle girls respectively,[258] whilst black hair is more common among lower-class girls (24.5%) than upper-middle class ones (9.0%).[258]

Chile was initially an unattractive place for migrants, because it was far from Europe and relatively difficult to reach. However, during the 18th century an influx of emigrants from Spain moved to Chile. They were mostly Basques, who rose rapidly up the social ladder, becoming part of the political elite that still dominates the country.[259][260] An estimated 1.6 million (10%) to 3.2 million (20%) Chileans have a surname (one or both) of Basque origin.[261][262][263][264][265][266][267][268] The Basques liked Chile because of its similarity to their native land: cool climate, with similar geography, fruits, seafood, and wine.[260]

The Spanish was the most significant European immigration to Chile,[269] although there was never a massive immigration, such as happened in neighboring Argentina and Uruguay,[270] and, therefore, the Chilean population wasn't "whitened" to the same extent.[270] However, it is undeniable that immigrants have played a role in Chilean society.[270] Between 1851 and 1924, Chile received only 0.5% of the total European immigration to Latin America, compared to 46% for Argentina, 33% for Brazil, 14% for Cuba, and 4% for Uruguay.[269] This was because such migrants came across the Atlantic, not the Pacific, and before the construction of the Panama Canal,[269] Europeans preferring to settle in countries close to their homelands, instead of taking the long route through the Straits of Magellan or across the Andes.[269] In 1907, the European-born reached a peak of 2.4% of the Chilean population,[271] decreasing to 1.8% in 1920,[272] and 1.5% in 1930.[273]

About 5% of the Chilean population has some French ancestry.[274] Over 700,000 (4.5%) Chileans may be of British (English, Scottish and Welsh) or Irish origin.[275] Another significant immigrant group is Croatian. The number of their descendants today is estimated to be 380,000, or 2.4% of the population.[276][277] Other authors claim that close to 4.6% of the Chilean population must have some Croatian ancestry.[278]

After the failed liberal revolution of 1848 in the German states,[270][279] a significant German immigration took place, laying the foundation for the German-Chilean community. Sponsored by the Chilean government, to "unbarbarize" and colonize the southern region,[270] these Germans (including German-speaking Swiss, Silesians, Alsatians and Austrians) settled mainly in Valdivia, Llanquihue, Chiloé, and Los Ángeles.[280] The Chilean Embassy in Germany estimated that 150,000 to 200,000 Chileans are of German origin.[281][282]

Colombia

[edit]According to the 2005 Census 86% of Colombians are considered either White or Mestizo, which are not categorized separately. Though the census does not identify the number of white Colombians, most sources estimate whites to make up 20% of the population,[2] while Hudson and Schwartzman put that figure at 37% of the population,[33] forming the second largest racial group after Mestizo Colombians (at 49-60%).[283] A genetic study by Rojas et al. estimates that the ethnic composition of Colombia is about 47% Amerindian, 42% European, and 11% African.[54]

Between 1540 and 1559, 8.9 percent of the residents of Colombia were of Basque origin. It has been suggested that the present day incidence of business entrepreneurship in the region of Antioquia is attributable to the Basque immigration and character traits. Today many Colombians of the Department of Antioquia region preserve their Basque ethnic heritage. In Bogota, there is a small district/colonies of Basque families who emigrated as a consequence of Spain's Civil War or because of better opportunities.[284] Basque priests were the ones that introduced handball into Colombia. Basque immigrants in Colombia were devoted to teaching and public administration. In the first years of the Andean Multinational Company, Basque sailors navigated as captains and pilots on the majority of the ships until the country was able to train its own crews.[285]

The first and largest wave of immigration from the Middle East began around 1880, and continued during the first two decades of the twentieth century. The immigrants were mainly Maronite Christians from Greater Syria (Syria and Lebanon) and Palestine, fleeing those then Ottoman territories.[286] Syrians, Palestinians, and Lebanese have continued to settle in Colombia. Due to a lack of information, it is impossible to know the exact number of Lebanese and Syrians that immigrated to Colombia; but for 1880 to 1930, 5,000–10,000 is estimated. Syrians and Lebanese are perhaps the biggest immigrant group next to the Spanish since independence. Those who left their homeland in the Middle East to settle in Colombia left for different religious, economic, and political reasons. In 1945, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Cali, and Bogota are the cities with the largest numbers of Arabic-speakers in Colombia.[287] The Arabs that went to Maicao were mostly Sunni Muslim, with some Druze and Shiites, as well as Orthodox and Maronite Christians. The mosque of Maicao is the second largest mosque in Latin America. Middle Easterns are generally called Turcos (Turkish).[286]

In December 1941 the United States government estimated that there were 4,000 Germans living in Colombia. There were some Nazi agitators in Colombia, such as Barranquilla businessman Emil Prufurt. Colombia invited Germans who were on the U.S. blacklist to leave.[288] SCADTA, a Colombian-German air transport corporation, which was established by German immigrants in 1919, was the first commercial airline in the western hemisphere.[289] In recent years, the celebration of Colombian-German heritage has grown increasingly popular in Bogota, Cartagena, and Bucaramanga. There are many annual festivals that focus German cuisine, specially pastry arts and beer. Since 2009, there has been a considerable increase in collaborative research through advanced business and educational exchanges, such as those promoted by COLCIENCIAS and AIESEC. There are many Colombian-German companies focused on finance, science, education, technology and innovation, and engineering.[290]

Ecuador

[edit]According to the most recent 2022 National Population census, 2.2% or 374,925 of the population identified as white, down from 2010, where 6.1% of the population self-identified as such, and down from 10.5% in 2001.[74][291] In Ecuador, being white is more an indication of social class than of ethnicity. Classifying oneself as white is often done to claim membership to the middle class and to distance oneself from the lower class, which is associated being "Indian". For this reason the status of blanco is claimed by people who are not primarily of European heritage.[292] According to genetic research done in 2008 by the University of Brasília, the average Ecuadorian genetic admixture is 64.6% Amerindian, 31.0% European, and 4.4% African.[160] In 2015, another study showed the average Ecuadorian is estimated to be 52.96% Amerindian, 41.77% European, and 5.26% Sub-Saharan African overall.[293]

White Ecuadorians, mostly criollos, are descendants of Spanish colonists and also Spanish refugees fleeing the 1936–1939 Spanish Civil War. Most still hold large amounts of lands, mainly in the northern Sierra, and live in Quito or Guayaquil. There is also a large number of white people in Cuenca, a city in the southern Andes of Ecuador, due to the arrival of Frenchmen in the area, who came to measure the arc of the Earth. Cuenca, Loja, and the Galápagos attracted German immigration during the early 20th century. The Galápagos also had a small Norwegian fishing community until they were asked to leave. There are large populations of Italian, French, German, Basque, Portuguese, and Greek descent, as well as a small Ecuadorian Jewish population. Ecuador's Jews consists of Sephardic Jews arriving in the South of the country in the 16th and 17th centuries and Ashkenazi Jews during the 1930s in the main cities of Quito and Cuenca.[294]

Paraguay

[edit]Ethnically, culturally, and socially, Paraguay has one of the most homogeneous populations in South America. Because of José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia's 1814 policy that no Spaniards and other Europeans could intermarry among themselves (they could only marry blacks, mulattoes, mestizos or the native Guaraní), a measure taken to avoid a white majority occurring in Paraguay (De Francia believed that all men were equal as well), it was within little more than one generation that most of the population were of mixed racial origin.[citation needed]

The exact percentage of the white Paraguayan population is not known because the Paraguayan census does not include racial or ethnic identification, save for the indigenous population,[295] which was 1.7% of the country's total in the 2002 census.[296] Other sources estimate the sizes of other groups, the mestizo population being estimated at 95% by the CIA World Factbook, with all other groups totaling 5%.[297][298] Thus, whites and the remaining groups (such as those of African descent) make up approximately 3.3% of the total population. According to Carlos Pastore, 30% are white and 70% approximately is mestizo.[12] Such a reading is complicated, because, as elsewhere in Latin America, "white" and "mestizo" are not mutually exclusive (people may identify as both).

Due to the European migration in the 19th and 20th centuries, the majority of Paraguay's white population are of German descent (including Mennonites), with others being of French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese descent.[299] Many are southern and southeastern Brazilians (brasiguayos), as well as Argentines and Uruguayans, and their descendants.[299] People from such regions are generally descendants of colonial settlers and/or more recent immigrants.[299]

In 2005, 600 families of Volga Germans who migrated to Germany after the fall of the Soviet Union, re-migrated and established a new colony, Neufeld, near Yuty (Caazapá Department), in southeastern Paraguay.[300]

Peru

[edit]

According to the 2017 census 5.9% or 1.3 million people self-identified as white of the population. This was the first time the census had asked an ancestral identity question. The highest proportion was in the La Libertad Region with 10% identifying as white.[85] They are descendants primarily of Spanish colonists, and also of Spanish refugees fleeing the Spanish Civil War. After World War II, many German refugees fled to Peru and settled in large cities, while others descend from Italian, French (mainly Basques), Austrian or German, Portuguese, British, Russians and Croatian immigrant families.

The regions with the highest proportion of self-identified whites were in La Libertad Region (10.5%), Tumbes Region and Lambayeque Region (9.0% each), Piura Region (8.1%), Callao (7.7%), Cajamarca Region (7.5%), Lima Province (7.2%) and Lima Region (6.0%).[85][301]

According to a genetic research by the University of Brasília, Peruvian genetic admixture indicates 73.0% Amerindian, 15.1% European, and 11.9% African ancestry.[160]

| White population by region, 2017[85] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Population | Percent | |||

| La Libertad | 144,606 | 10.5% | |||

| Tumbes | 15,383 | 9.0% | |||

| Lambayeque | 83,908 | 9.0% | |||

| Piura | 114,682 | 8.1% | |||

| Callao | 61,576 | 7.7% | |||

| Cajamarca | 76,953 | 7.5% | |||

| Lima Province | 507,039 | 7.2% | |||

| Lima | 43,074 | 6.0% | |||

| Ica | 38,119 | 5.8% | |||

| Ancash | 49,175 | 5.8% | |||

| Arequipa | 55,093 | 4.9% | |||

| Amazonas | 12,470 | 4.4% | |||

| Huánuco | 24,130 | 4.4% | |||

| San Martín | 24,516 | 4.0% | |||

| Moquegua | 5,703 | 4.0% | |||

| Pasco | 7,448 | 3.8% | |||

| Junín | 34,700 | 3.6% | |||

| Madre de Dios | 3,444 | 3.3% | |||

| Tacna | 8,678 | 3.2% | |||

| Ucayali | 8,283 | 2.3% | |||

| Ayacucho | 9,516 | 2.0% | |||

| Huancavelica | 5,222 | 2.0% | |||

| Loreto | 11,884 | 1.9% | |||

| Cusco | 12,458 | 1.3% | |||

| Apurímac | 3,034 | 1.0% | |||

| Puno | 5,837 | 0.6% | |||

| Republic of Peru | 1,336,931 | 5.9% | |||

Uruguay

[edit]A 2009 DNA study in the American Journal of Human Biology showed the genetic composition of Uruguay as primarily European, with Native American ancestry ranging from one to 20 percent and sub-Saharan African from seven to 15 percent, depending on the region.[302]

Between the mid-19th and the early 20th centuries, Uruguay received part of the same migratory influx as Argentina, although the process started a bit earlier. During 1850–1900, the country welcomed four waves of European immigrants, mainly Spaniards, Italians and Frenchmen. In smaller numbers came British, Germans, Swiss, Russians, Portuguese, Poles, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Estonians, Dutch, Belgians, Croatians, Lebanese, Armenians, Greeks, Scandinavians, and Irish. The demographic impact of these migratory waves was greater than in Argentina, Uruguay going from having 70,000 inhabitants in 1830, to 450,000 in 1875, and a million inhabitants by 1900, its population thus increasing fourteen-fold in only 70 years. Between 1840 and 1890, 50%–60% of Montevideo's population was born abroad, almost all in Europe. The Census conducted in 1860 showed that 35% of the country's population was made up by foreigners, although by the time of the 1908 Census this figure had dropped to 17%.[303]

From 1996 to 1997, the National Institute of Statistics (INE) of Uruguay conducted a Continuous Household Survey, of 40,000 homes, that included the topic of race in the country. Its results were based on "the explicit statements of the interviewee about the race they consider they belong themselves". These results were extrapolated, and the INE estimated that out of 2,790,600 inhabitants, some 2,602,200 were white (93.2%), some 164,200 (5.9%) were totally or partially black, some 12,100 were totally or partially Amerindian (0.4%), and the remaining 12,000 considered themselves Yellow.[304]

In 2006, a new Enhanced National Household Survey touched on the topic again, but this time emphasizing ancestry, not race; the results revealed 5.8% more Uruguayans self-reported stated having total or partial black and/or Amerindian ancestry. This reduction in the percentage of self-declared "pure whites" between surveys could be caused by the phenomenon of the interviewee giving new value to their African heritage, similar to what has happened in Brazil in the last three censuses. Anyway, it is worth noting that 2,897,525 interviewées declared having only white ancestry (87.4%), 302,460 declared having total or partial black ancestry (9.1%), 106,368 total or partial Amerindian ancestry (2.9%) and 6,549 total or partial Yellow ancestry (0.2%).[305] This figure matches external estimates for white population in Uruguay of 87.4%,[306] 88%,[2][307] or 90%.[308]

In 1997, the Uruguayan government granted residence rights to only 200 European/American citizens; in 2008 the number of residence rights granted increased to 927.[309]

Venezuela

[edit]According to the official Venezuelan census, although "white" literally involves external issues such as light skin, shape and color of hair and eyes, among others, the term "white" has been used in different ways in different historical periods and places, so its precise definition is somewhat confusing.[8] Though the 2011 Venezuelan Census states that "White" in Venezuela is used to describe the Venezuelans of European origin.[310]

According to the 2011 National Population and Housing Census, 43.6% of the population identified themselves as white people.[8] A genomic study shows that about 60.6% of the Venezuelan gene pool has European origin. Among the countries in the study (Argentina, Bahamas, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, El Salvador, Ecuador, Jamaica, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela), Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, and Argentina exhibit the highest European contribution.[160]

The Venezuelan gene pool indicates a 60.6% European, 23.0% Amerindian, and 16.3% African ancestry.[160] Spaniards were introduced into Venezuela during the colonial period. Most of them were from Andalusia, Galicia, Basque Country and from the Canary Islands. Until the last years of World War II, a large part of European immigrants to Venezuela came from the Canary Islands, and their cultural impact was significant, influencing its gastronomy, customs and the development of Castilian in the country. With the beginning of oil production during the first decades of the 20th century, employees of oil companies from the United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands established themselves in Venezuela. Later, in the middle of the century, there was a new wave of immigrants originating from Spain (mainly from Galicia, Andalucia, and Basque country, some being refugees from the Spanish Civil War), Italy (mainly from southern Italy and the Veneto region), and Portugal (from Madeira), as well as from Germany, France, England, Croatia, the Netherlands, and other European countries encouraged by a welcoming immigration policy to a prosperous, rapidly developing country where educated and skilled immigrants were needed.[citation needed]

Representation in the media

[edit]Some media outlets in the United States have criticized Latin American media for allegedly featuring a disproportionate number of blond and blue-eyed actors and actresses in telenovelas, relative to the overall population.[311][312][313][314]

See also

[edit]- Afro-Latin Americans

- Asian Latin Americans

- Blanqueamiento

- Carcamano

- Castizo

- European diaspora

- Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Latin Americans

- Mestizo

- Mulatto

- Peninsulares

- Race and ethnicity in Latin America

- Racism in South America

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Portuguese colonization of the Americas

References

[edit]- ^ a b CIA data from The World Factbook's Field Listing :: Ethnic groups and Field Listing :: Population, retrieved on May 09 2011. They show 191,543,213 whites from a total population of 579,092,570. For a few countries the percentage of white population is not provided as a standalone figure, and thus that datum is considered to be not available; for example, in Chile's case the CIA states "white and white-Amerindian 95.4%". Unequivocal data are given for the following: Argentina 41,769,726 * 97% white = 40,516,634; Bolivia 10,118,683 * 5% white = 505,934; Brazil 203,429,773 * 53.7% white = 109,241,788; Colombia 44,725,543 * 20% white = 8,945,109; Cuba 11,087,330 * 65.1% white = 7,217,852; Dominican Republic 9,956,648 * 16% white = 1,593,064; El Salvador 6,071,774 * 9% white = 546,460; Honduras 8,143,564 * 1% white = 81,436; Mexico 113,724,226 * 9% white = 10,235,180; Nicaragua 5,666,301 * 17% white = 963,272; Panama 3,460,462 * 10% white = 346,046; Peru 29,248,943 * 15% white = 4,387,342; Puerto Rico 3,989,133 * 76.2% white = 3,039,719; Uruguay 3,308,535 * 88% white = 2,911,511. Total white population in these countries: 191,543,213, i.e 33.07% of the region's population.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (August 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of the Three Cultural Areas of the American Continent at the Beginning of the 21st Century]. Convergencia (in Spanish). 12 (38): 185–232.

- ^ a b c "Censo Demográfico 2010: Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência" [Census 2010: general characteristics of the population, religion and people with disabilities]. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (in Portuguese). 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ a b c About one third"Mexico: Ethnic groups". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "21 de Marzo: Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial" [March 21: International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: CONAPRED. 2017. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico 2010" [National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico 2010] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: CONAPRED. June 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Raza/Etnia a la que pertenece". Latinobarómetro 2023 Colombia. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Resultado Básico del XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2011 (Mayo 2014)" (PDF). Ine.gov.ve. p. 29. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b "DEMOGRÁFICOS : Censos de Población y Vivienda". Ine.gov.ve. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Censo de Población y Viviendas de Cuba de 2012" (PDF). almendron. 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Uruguay: People and Society". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ a b Pastore, Carlos (1972). La lucha por la tierra en el Paraguay: Proceso histórico y legislativo. Antequera. p. 526.

- ^ a b c d "REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA: Población de 12 años y más, por percepción del informante acerca de las facciones, color de piel y otras características culturales de los miembros del hogar, según región, provincia y grupos de edades". one.gob.do. 30 September 2024. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. p. 214. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "El Salvador-The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b Nuñez, Carolina; Baeta, Miriam; Sosa, Cecilia; Casalod, Yolanda; Ge, Jianye; Budowle, Bruce; Martínez-Jarreta, Begoña (December 2010). "Reconstructing the population history of Nicaragua by means of mtDNA, Y-chromosome STRs, and autosomal STR markers". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 143 (4): 591–600. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21355. PMID 20721944.

- ^ a b c d "2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country". United States Census. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ 2.2% or 374,925 of the Ecuadorian population identified as white in the 2022 census.

- ^ "Ecuador: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022" (PDF). censoecuador.gob.ec. 21 September 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ José Reyes Alveo. "Población panameña (página 2)". Monografias.com. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Honduras; People; Ethnic groups". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ More precisely, these are the chief languages of Latin America, as per CIA – The World Factbook – Field Listing :: Languages, accessed 2010-02-24.

- ^ The religious profile of the Latin American countries can be seen in CIA – The World Factbook – Field Listing :: Religions (accessed 2010-02-24). As such, it is not the religious profile of white Latin Americans in particular, but is a good indication of white religious affiliation in the region's white-majority countries, especially.

- ^ Ramón Grosfoguel, Nelson Maldonado-Torres, José David Saldívar (April 15, 2006). "Latin@s in the World-System: Decolonization Struggles in the 21st Century U.S. Empire". dlcl.stanford.edu.

Latino/as are multiracial (Afro-Latinos, Indo-Latinos, Asian-Latinos, and Euro-Latinos)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Various (2001). "Introduction". In Agustín Laó-Montes and Arlene Dávila (ed.). Mambo Montage: The Latinization of New York City. Columbia University Press.

For instance, in the global chain of otherness, upper-class Euro-Latinos can be located... (p. 10)

- ^ Chambers, Sarah C. (2003). "Little Middle Ground The Instability of a Mestizo Identity in the Andes, 18th and 19th centuries". In Nancy P. Appelbaum (ed.). Race and Nation in Modern Latin American. University of North Carolina Press.

This blending of culture and genealogy is also reflected in the use of the terms "Spanish" and "white". For most of the colonial period, Americans of European descent were simply referred to as "Spaniards"; beginning in the late 18th century, the term "blanco" (white) came into increasing but not exclusive use. Even those of presumably mixed ancestry may have felt justified in claiming to be Spanish (and later white) if they participated in the dominant culture by, for example, speaking Spanish and wearing European clothing.(p. 33)

- ^ a b South America: Postindependence overseas immigrants. Encyclopædia Britannica Retrieved 26-11-2007

- ^ Schrover, Marlou. "Migration to Latin America". Retrieved 2010-02-24.[permanent dead link]

- ^ CELADE (Organization) (2001). International migration and development in the Americas. Naciones Unidas, CEPAL/ECLAC, Population Division, Latin American and Caribbean Demographic Centre (CELADE). ISBN 9789211213287.

- ^ Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (2004). "Las etnias centroamericanas en la segunda mitad del siglo XX". Revista Mexicana del Caribe. 9 (17): 7–43. Gale A466617637.

- ^ Schaefer, Richard T., ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity and Society. Sage. p. 900. ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2.

In New Spain, there was no strict idea of race (something that continued in Mexico). The Indians that had lost their connections with their communities and had adopted different cultural elements could "pass" and be considered mestizos. The same applied to blacks and castas. Rather, the factor that distinguished the various social groups was their calidad ("quality"); this concept was related to an idea of blood as conferring status, but there were also other elements, such as occupation and marriage, that could have the effect of blanqueamiento (whitening) on people and influence their upward social mobility.

- ^ Schaefer, Richard T., ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity and Society. Sage. p. 1096. ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2.

The variation of racial groupings between nations is at least partially explained by an unstable coupling between historical patterns of colonization and miscegenation. First, divergent patterns of colonization may account for differences in the construction of racial groupings, as evidenced in Latin America, which was colonized primarily by the Spanish. The Spanish colonials had a longer history of tolerance of non-White racial groupings through their interactions with the Moors and North African social groups, as well as a different understanding of the rights of colonized subjects and a different pattern of economic development.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Simon (2008). "Etnia, condiciones de vida y discriminacion" (PDF). In Valenzuela, Eduardo; Schwartzman, Simón; Biehl, Andrés; Valenzuela, J. Samuel (eds.). Vínculos, Creencias e Ilusiones: La cohesión social de los Latinoamericanos. Uqbar Editores. ISBN 978-956-8601-17-1.

- ^ Chambers, Sarah C. (2003). "Little Middle Ground The Instability of a Mestizo Identity in the Andes, 18th and 19th centuries". In Nancy P. Appelbaum (ed.). Race and Nation in Modern Latin American. University of North Carolina Press.

This blending of culture and genealogy is also reflected in the use of the terms Spanish and white. For most of the colonial period, Americans of European descent were simply referred to as Spaniards; beginning in the late 18th century, the term blanco (white) came into increasing but not exclusive use. Even those of presumably mixed ancestry may have felt justified in claiming to be Spanish (and later white) if they participated in the dominant culture by, for example, speaking Spanish and wearing European clothing.(p. 33)

- ^ Wade, Peter (1997). Race And Ethnicity In Latin America. Pluto Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7453-0987-3.

- ^ Levine-Rasky, Cynthia. 2002. "Working through whiteness: international perspectives. SUNY Press (p. 73) " 'Money whitens' If any phrase encapsulates the association of whiteness and the modern in Latin America, this is it. It is a cliché formulated and reformulated throughout the region, a truism dependent upon the social experience that wealth is associated with whiteness, and that in obtaining the former one may become aligned with the latter (and vice versa)."

- ^ IBGE. "IBGE - sala de imprensa - notícias". ibge.gov.br.