Eugen Kvaternik

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Eugen Kvaternik | |

|---|---|

Eugen Kvaternik's lithograph by Stjepan Kovačević | |

| President of the Provisional government of United Croatia | |

| In office 8 October 1871 – 11 October 1871 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 October 1825 Zagreb, Croatia, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 11 October 1871 (aged 45) Ljubča, Rakovica, Austria-Hungary (now Rakovica, Croatia) |

| Citizenship | Austria (1825–1867)Austria-Hungary (1867–1871)Russia[1] |

| Nationality | Croat |

| Political party | Party of Rights |

| Alma mater | University of Pécs |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Eugen Kvaternik (Croatian pronunciation: [ěugen kʋǎternik]; 31 October 1825 – 11 October 1871) was a Croatian nationalist[2][3][4] politician and one of the founders of the Party of Rights, alongside Ante Starčević. Kvaternik was the leader of the 1871 Rakovica Revolt which was an attempt to create an independent Croatian state, at the time when it was part of Austria-Hungary. In order to get foreign support for his cause Kvaternik visited the Russian Empire, France and the Kingdom of Sardinia. He was also well known for anti-Austro-Hungarian speeches that he made as member of the Croatian Parliament.[5]

Early life

[edit]Kvaternik was born in Zagreb. He was educated in Senj and in Pest. After the abolition of feudalism in 1848 by ban Josip Jelačić, greater freedom from the Austrian Empire was granted. This encouraged proponents of Croatian independence such as Kvaternik. In 1857, the Austrian authorities forbade him to work as a lawyer, leaving him unemployed.[citation needed]

Political and revolutionary activity

[edit]In 1858 Kvaternik decided to leave for the Russian Empire, seeking an ally against the Austrian state. He was aware that Russia was aggrieved because Austria had not joined the Crimea War. While in Russia, Kvaternik gained its citizenship, but soon realized that he would get no military help. In spring 1859 he left for Torino. With help from Niccolò Tommaseo he met with various Italian statesmen and politicians. One of them was Italian prime minister Camillo Benso di Cavour and minister of justice Urbano Rattazzi. Kvaternik succeeded to arrange a meeting with them more easily because the Kingdom of Sardinia was just about to ally with Napoleon III of France to attack Austria.[1]

The Croatian Grenzers saved the Austrian Empire many times. Kvaternik promised that he would get loyalty of the Grenzers to help Cavour in his war against Austria. Kvaternik knew that the Grenzers were unhappy with the Austrian payments to them after the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. He issued an announcement in Croatian to the Grenzers not to help Austria in their war against the Italians. Kvaternik's announcement had a strong impact as the Grenzers were suffering from low morale while fighting in the Battle of Solferino. Austrians rushed to sign a peace with the French.[1]

Nevertheless, Kvaternik believed that the Grenzers would play a significant role in the liberation of Croatia. He continued negotiations with the Italian and Hungarian emigration and offered the Croatian crown to the Prince Napoléon Joseph Charles, the Emperor's cousin and son-in-law of Italian King Victor Emmanuel II. After Napoléon refused the crown, he offered it to a Polish noble Władysław Czartoryski, who was a fellow Catholic Slav. Kvaternik and his Italian and Hungarian allies made a plan to destroy Austria by instigating simultaneous revolts in both the Croatian Military Frontier and in Venice, while Giuseppe Garibaldi would land his troops in the northern Dalmatia. After that they counted on Hungarian and Romanian help with support of the Sardinian Kingdom and France. They also knew that Russia and Prussian Kingdom wouldn't offer any help to Austria. However, in 1865 the plan was withdrawn as Napoleon of France stopped giving any help and thus forced Italy into inaction.[6]

In March 1860, Kvaternik claimed to Napoléon that Croatia could provide some 250,000 soldiers, explaining that Croats were able to do so when they fought the Hungarians in the 1848 Revolution. A month later, he stated to the Sardinian ambassador (Costantino Nigra) that Croats still hoped for revolution and could raise some 400,000 men and liberate Venice. Kvaternik was, however, more active during his stay in Italy between 1863 and 1865. As a member of the Croatian Sabor since 1861, Kvaternik become popular among those who disliked Austria, and at the same time he was still in contact with the Grenzers.[citation needed]

In March 1864, he made a revolutionary plan, anticipating the creation of the Croatian people's government and also started to publish a revolutionary newspaper in Geneva. In April 1864 he claimed to the Sardinian foreign ministry that Slavonia could provide some 300,000 men. The next month he claimed he could transfer the Granzers into "free Italy" in order to help the revolt.[7]

Rakovica revolt

[edit]Political situation in Austria-Hungary

[edit]

After the dual monarchy was created in 1867, Germans and Hungarians become the most influential people in the monarchy, leaving Slavs, such as Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Serbs and Slovenes, in an unprivileged position.[clarification needed] The Prussian ambassador in Vienna, General Schweinitz, reported that the Czechs were trying to destroy the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy and that the Germans and Hungarians feared the monarchy would approach the Russian Empire for help. Hungarians were also aware that Emperor Franz Joseph was counting on Russian help to avenge his defeat at Königgrätz from 1866.[citation needed]

The Czech effort to crush the monarchy were so strong that they overthrown the dualist government of Alfred Potocki. After Potocki's removal, Franz Joseph named Karl von Hohenwart new Minister-President of Cisleithania. Hohenwart advocated federalism and collapse of the dualist policy. The main opponents of Hohenwart's policy were Hungarian nationalists, namely Prime Minister of Hungary Gyula Andrássy and his government. Franz Joseph had a plan to deal with the Hungarians once he solved the problem with the Czechs. Austria-Hungary entered a fierce political struggle. Hohenwarth was dealing with the Czechs, while Friedrich von Beust, the foreign minister and chairman of the joint government, dealt with Andrássy. Hohenwarth, nevertheless, was successful at the beginning. In September 1871, the Emperor recognized the Czech Kingdom and promised to crown himself as its king in Prague. It was the first sign that dualist policy would collapse in favour of federalism. As Andrássy was disappointed by this move, he forced von Beust to give a memorandum against Hohenwarth to the Emperor in October, however, the Emperor continued to give his thrust to Hohenwart.[8]

Preparations for the Rakovica revolt

[edit]While in Torino in June 1864, Kvaternik met with Ante Rakijaš, a former military cadet who had deserted. Rakijaš, a Croatian nationalist educated in Graz, served as Kvaternik's main assistant. In November 1864 both of them planned a revolt that would occur in spring 1865. Rakijaš obtained a fake passport and moved from Torino to Ancona, waiting for a chance to enter Dalmatia. In early 1865 he went to Brač, and from there to Split and later to Sinj, from where he went to Knin. In Knin, he tried to instigate an uprising. He failed and was arrested and sentenced to eleven months in prison in Zadar.[citation needed]

Due to the arrest of Rakijaš, Kvaternik realized that their plan for a revolt had failed, so he also returned to Croatia. But just as he arrived to Zagreb, he was soon forced to flee as he was a Russian citizen, and as such he was dangerous to the authorities. His expulsion was ordered by Ban Josip Šokčević, who hated him as well as members of the Party of Rights; Šokčević was advised to do so by Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer.

After Austria was defeated by Prussia in the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866 and after Franz Joseph I of Austria was crowned as Hungarian king in 1867, Kvaternik got amnesty from the Austrian Emperor and approval for his return. Ban Levin Rauch also gave him Austrian citizenship and permitted him to work as a lawyer. As of then, Kvaternik worked as a lawyer and also dealt with history. He published his book "Eastern Question and the Croats" in two volumes. Kvaternik was also involved in publishing activities; between 1868 and 1870 he wrote for the magazine Hrvat (The Croat). In 1871 he was publishing an official newspaper of the "Party of Rights Hrvatska".[9]

Meanwhile, Rakijaš was released from prison and went to Zagreb where he closely cooperated with Kvaternik. Rakijaš soon moved to Karlovac and was employed as a police officer with Kvaternik's help by captain Fabiani, a supporter of the Party of Rights. The Grenzers would be in Karlovac on every Friday, which Rakijaš used to explain them the political situation. Croats were disappointed by creation of the dual monarchy in 1867, and with the Croatian-Hungarian Agreement in 1868, but were pleased with the unification of the Military Frontier with rest of Croatia. However, the people of the Military Frontier feared the Hungarian influence and higher taxes.[10]

Revolt

[edit]

In May 1871, Kvaternik wasn't elected to the Sabor, so in October he abandoned his party's aim of only using political resistance and launched the Rakovica Revolt, just when the Austria-Hungary was in the process of federalization.[11] Kvaternik believed that once he started the revolt, the unhappy Grenzers would join him. His goal was the liberation of Croatia and the unification of its lands. He planned to proclaim the Croatian People's Government after a projected meeting with the Grenzers, after which he would arm the people from Slunj, Ogulin, and the Isle regiments and Rakovica. Then he planned to move towards Ogulin and Karlovac from where he would go to Zagreb where he would proclaim the liberation for the second time and ask the European countries for their recognition and protection. He was bolstered by the fact that Austria-Hungary was isolated at the time, without strong allies.[12]

In October 1871, Kvaternik left Zagreb, met with Rakijaš in Karlovac and went with him to Broćanac, where he arrived on the evening on 7 October. The revolutionaries held a meeting in Broćanac and formed the transitional Croatian People's Government. Kvaternik was named president. Petar Vrdoljak was named minister of interior, Ante Rakijaš was named minister of defence and Vjekoslav Bach, a lawyer from Zagreb, was named minister of finance. Rade Čuić, another revolutionary, was named commander of the ustaše (uprising), a commander of the armed forces respectively, while Ante Turkalj was named prefect of the Ogulin region.

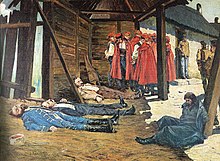

The next day, Sunday, 8 October, Kvaternik launched the revolt. With some 200 Grenzers Kvaternik moved towards Rakovica with the Croatian flag. He was accompanied by Bach. The building of their government was supposed to be in house of a merchant, Ivo Vučić, a local from Rakovica. As they arrived, they arrested those Grenzers who would not join them and took their arms. They started to organize the revolt. Nearby villages also joined them, including Broćanac, Brezovac, Mašvina, Plavća Draga and Močila.[13]

The revolt, however, ended unsuccessfully and Kvaternik was killed while trying to break out of Austro-Hungarian Army's encirclement.[14] Squares in Zagreb and Čakovec, the Eugen Kvaternik Squares, are named after him, as is a street in Osijek, Ulica Eugena Kvaternika.

"I hate neither Hungary nor Austria and all that I do I do out of immense love of Croatia." – Eugen Kvaternik [citation needed]

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b c Šišić 1926, p. 8.

- ^ Jozo Tomasevich, War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941 - 1945, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2001, S.348

- ^ Lars-Erik Cederman, Emergent Actors in World Politics: How States and Nations Develop and Dissolve, Princeton University Press, 1997, S.207

- ^ Ljiljana Šarić, Contesting Europe's Eastern Rim: Cultural Identities in Public Discourse, 2010, S.100

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 5.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 9.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 10-11.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 14.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 12.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 13.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 13-14.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 16-17.

- ^ Šišić 1926, p. 19-20.

- ^ "Rakovička buna | Hrvatska enciklopedija".

- Bibliography

- Šišić, Ferdo (1926). Kvaternik (Rakovička buna) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Tisak Hrvatskog štamparskog zavoda.

Further reading

[edit]- Markus, Tomislav (June 1998). "Eugen Kvaternik u hrvatskoj politici i publicistici 1859.-1871. godine" (PDF). Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 16 (16): 159–222. Retrieved 1 December 2017.