Ethnic groups in the United Kingdom

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

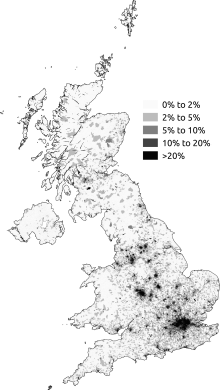

The United Kingdom is an ethnically diverse society. The largest ethnic group in the United Kingdom is White British, followed by Asian British. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom is formally recorded at the national level through a census. The 2011 United Kingdom census recorded a reduced share of White British people in the United Kingdom from the previous 2001 United Kingdom census. Factors that are contributing to the growth of minority populations are varied in nature, including differing birth rates and Immigration.

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) based on population survey figures from 2019, people from ethnic minority backgrounds make up 14.4% of the United Kingdom (16.1% for England, 5.9% for Wales, 5.4% for Scotland and 2.2% for Northern Ireland).[1]

History

[edit]A variety of ethnic groups have settled on the British Isles, dating back from the last ice age up until the 11th century. These populations included the Celtic Britons (including the Picts), Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Gaelic Scots, Norse, Danes and the Normans.[2] Recent genetic studies have suggested that the prehistoric Bell Beaker influx and the Anglo-Saxon migrations had particularly significant effects on the genetic makeup of modern Britons.[3][4][5][6]

King William the Conqueror, introduced the first Jewish settlers in England in 1070,[7] and later on, in the 16th century, the first Romani were introduced in Britain. The UK has a history of small-scale non-European immigration, with Liverpool having the oldest Black British community dating back to at least the 1730s, during the period of the African slave trade.[8] The oldest Chinese community in Europe, dates back to the arrival of Chinese seamen in the 19th century.[9] In the 19th century, there was an increase of Jewish and Irish people living in Great Britain, with many settling in Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and in The East End Of London, where the ethnic dialects contributed to the formation of the Cockney dialect.

Since 1948 and particularly from the mid-1950s, immigration from the West Indies and the Indian Subcontinent occurred in substantial numbers due to labour shortages in Britain after World War II.[10] Immigration started to increase in the 1950s and 1960s and the large influx of different cultures created different ethnic communities. However, instances of documented and perceived racism, and heavy-handed policing by the native English population, has led to a number of riots, most notably in 1958, 1981, 1985 and 2011. When Britain joined the EEC in 1973, the level of migration from Western European nations increased and migration from newer EU member states in Central, and Eastern Europe, have resulted in a large Eastern European population over the past 2 decades. However, after the Brexit Referendum in 2016, numbers began to decline once again.[11]

Sociologist Steven Vertovec presents the idea of superdiversity in Britain, a notion that states that the increasing population of ethnic groups and communities are creating new, and smaller, ethnic minorities in Britain. The dynamics of superdiversity influence the social and economic patterns of the United Kingdom and have created complex social frameworks.[12]

Official classification of ethnicity

[edit]

The definition of ethnicity has been defined as "the social group a person belongs to, and either identifies with or is identified with by others, as a result of a mix of cultural and other factors including language, diet, religion, ancestry and physical features traditionally associated with race".[14]

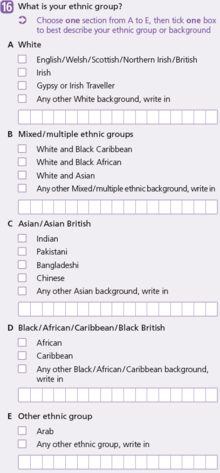

The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity.[15][16] The 2001 UK Census classified ethnicity into several groups: White, Black, Asian, Mixed, Chinese and Other.[17][18] These categories formed the basis for all National Ethnicity statistics until the 2011 Census results were issued.[18] A number of academics have pointed out that since 1991, the ethnicity classification employed in the census, alongside other official statistics in the UK have high levels of confusion regarding the concepts of ethnicity and race.[19][20] David I. Kertzer and Dominique Arel argue that this is the case in many censuses, and the definition of ethnicity should first be illuminated.[20] User consultation undertaken for the purpose of planning the 2011 census revealed that some participants thought the "use of colour (White and Black) to define ethnicity is confusing or unacceptable".[21]

Population by ethnicity

[edit]

The population of the United Kingdom and its constituent countries are ethnically diverse today. From the beginning of modern migration to the country, the White population has been in proportional decline; however, the question of ethnicity was only first asked in the 1991 census. In the four pie charts below shows the ethnic make up of each country of the United Kingdom and as a whole over time.

- Ethnicities of United Kingdom and in its constituent countries

National minorities

[edit]The British government recognises the Scottish, Welsh, Irish and Cornish peoples as national minorities under the Council of Europe's Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, which the UK signed in 1995 and ratified in 1998.[22]

A proposal for Longitudinal Study of Ethnic Minorities (LSEM) was suggested by sociologist James Nazroo to create designated ethnic groups under Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Caribbean and Black African.[23] The LSEM understood the constraints of the oversampling of groups and refined the methods of categorising the ethnic minorities.

Multiculturalism and integration

[edit]It is estimated that in 1950 there were no more than 20,000 non-white residents in the United Kingdom, almost all having been born outside the UK and now mainly residing in England.[24]

However, the considerable migration after World War II increased the ethnic and racial diversity of UK, especially in London. The race relations policies that have been developed broadly reflect the principles of multiculturalism, although there is no official national commitment to multiculturalism.[25][26][27]

The national identity of 'being British' is to respect the laws and parliamentary structures, as well as all maintaining the right to equality; however, this does not cover the concept of multiculturalism. This concept of 'being British' faces criticism on the grounds that it has failed to sufficiently promote social integration,.[28][29][30] Some commentators have questioned the dichotomy between diversity and integration.[29] and since 2001 it has been argued that the UK government has moved away from policy characterised by multiculturalism, and towards the assimilation of minority communities.[31]

In 2016, the British government held a European Union membership referendum. The result of the referendum showed that 51.9% of British voters wanted to leave the EU[32] and on 31 January 2020, the deal was reached for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to leave the EU on 1 January 2021, also known as Brexit, with terms being agreed to on 24 December 2020.[3] Some have said that Brexit limits multiculturalism and encourages exclusive nationalism and nativism; however, some feel that Brexit supports traditional British identity.[6]

Attitudes to multiculturalism

[edit]A poll conducted by MORI for the BBC in 2005 found that 62 per cent of respondents agreed that multiculturalism made the UK a better place to live, compared to 32 percent who saw it as a threat.[33] In contrast, Ipsos MORI data from 2008 showed that only 30 per cent saw multiculturalism as making the UK a better place to live, with 38 per cent seeing it as a threat. 41 per cent of respondents to the 2008 poll favoured the development of a shared identity over the celebration of diverse values and cultures, with 27 per cent favouring the latter and 30 per cent undecided.[34]

A study conducted for the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) in 2005, found that in England, the majority of ethnic minority participants called themselves British, whereas white English participants said English first and British second. In Wales and Scotland the majority of white and ethnic minority participants identified with Welsh or Scottish first and British second.[35] Research suggests that on average ethnic minorities are twice as likely to say their ethnicity is important to them than white British participants, although the extent of this difference also interacted with political beliefs.[36]

Other research conducted for the CRE found that white participants felt that there was a threat to Britishness from large-scale immigration, claiming that they perceived ethnic minorities made a rise in moral pluralism and political correctness. Much of this frustration was directed at Muslims rather than minorities in general. Muslim participants in the study reported feeling victimised and stated that they felt the pressure of choosing between Muslim and British identities, whereas they saw it possible to be both.[37]

Political representation

[edit]Ethnic minorities have been under-represented in comparison with their white counterparts in the United Kingdom's political system, particularly in the British Parliament.[38] In 1981, the Home Affairs Select Committee report stated that an "increase in ethnic minority involvement in politics will create ... special representation for ethnic minorities".[39] However, in 2017 Theresa May stated that ethnic minorities were still under-represented.[40] In 2019, 65 Members of Parliament (MPs) or 10% of all MPs were from an ethnic minority background.[41]

Representation in Parliament

[edit]Representation of ethnic minorities in Parliament began in 1987, seeing four ethnic minorities being elected into parliament. Among them was Diane Abbott, Britain's first black female Member of Parliament, who began as a member of the shadow cabinet and was a prominent figure within the Labour Party.[42]

Prior to the 2010 elections, the Conservatives had 2 MPs who were minorities and this increased to 11 after the 2010 General Election.[43] After the 2017 General Elections, 52 minority MPs were elected, shared between Labour (32) and the Conservative (19) and one from the Liberal Democrats.[44] The 2019 general elections showed an increase in these numbers with Labour having 41, the Conservatives having 22 and the Liberal Democrats having 2 ethnic-minority MPs.[41]

Representation in Local Councils

[edit]In 2018, 3.7% of all local government officials had an ethnic minority background.[45] London councils had the highest percentage for representation in their local councils in late 2017, 10.5%; this increased from 5.6% previously in the year.[45] Outside London, councils have an average of 3% minority representation.[45] In Scotland, 3.2% of local government officials are ethnic minorities, almost proportionately representing the 3.32% ethnic minority.[46]

Since the 1980s, the number of minority councillors has been increasing over time, however, the main parties of minorities involved were the Labour party, with 94.4% of minority councillors affiliated with the Labour Party.[39]

There were 35 minority councillors in London local councils in 1978 and this had increased to 193 by 1990.[39] This was 10% of the 1,915 councillors representing 20% of London's population.[39] According to a Census of Local Authority Councillors in 2013, there was 3.7% representation for minorities across all councils, compared to a representation of 13% nationally.[47] Labour continues to have the largest proportion of ethnic minority councillors with 9.2%, followed by the Conservatives with 1.5%.[47]

See also

[edit]- Ethnic groups in London

- British people

- Demographics of the United Kingdom

- Foreign-born population of the United Kingdom

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Historical immigration to Great Britain

- Modern immigration to the United Kingdom

- Languages of the United Kingdom

- List of electoral firsts in the United Kingdom

- Romanichal

References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Ian (31 March 2021). "Latest figures on ethnic diversity in the UK".

- ^ Duffy, Jonathan (20 April 2001). "Are the British a race?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2003. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ a b McNish, James. "The Beaker people: a new population for ancient Britain". Natural History Museum, London.

- ^ Coghlan, Andy. "Ancient invaders transformed Britain, but not its DNA". New Scientist.

- ^ Schiffels, S.; Haak, W.; Paajanen, P. (2016). "Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history". Nature Communications. 7 (10408): 10408. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710408S. doi:10.1038/ncomms10408. PMC 4735688. PMID 26783965.

- ^ a b Martiniano, R.; Caffell, A.; Holst, M. (2016). "Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons". Nature Communications. 7 (10326): 10326. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710326M. doi:10.1038/ncomms10326. PMC 4735653. PMID 26783717.

- ^ "Jewish communities from the 1070s - Reasons for immigration in the Medieval era - OCR A - GCSE History Revision - OCR A". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Costello, Ray (2001). Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain's Oldest Black Community 1730–1918. Liverpool: Picton Press. ISBN 978-1-873245-07-1.

- ^ "Culture and Ethnicity Differences in Liverpool – Chinese Community". Chambré Hardman Trust. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Short History of Immigration". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Vargas-Silva, Carlos (10 April 2014). "Migration Flows of A8 and other EU Migrants to and from the UK". Migration Observatory, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Vertovec, Steven (2007). "Super-diversity and its implications". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465. S2CID 143674657.

- ^ "Harmonised Concepts and Questions for Social Data Sources - Primary Standards: Ethnic Group" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Bhopal, R. (1 June 2004). "Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 58 (6): 441–445. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.013466. ISSN 0143-005X. PMC 1732794. PMID 15143107.

- ^ "How has ethnic diversity grown 1991-2001-2011?" (PDF). ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity. December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Sillitoe, K.; White, P. H. (1992). "Ethnic Group and the British Census: The Search for a Question". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (Statistics in Society). 155 (1): 141–163. doi:10.2307/2982673. JSTOR 2982673. PMID 12159122.

- ^ "Presenting ethnic and national groups data". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ a b "How do you define ethnicity?". Office for National Statistics. 4 November 2003. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ Ballard, Roger (1996). "Negotiating race and ethnicity: Exploring the implications of the 1991 census" (PDF). Patterns of Prejudice. 30 (3): 3–33. doi:10.1080/0031322X.1996.9970192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-11. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ a b Kertzer, David I.; Arel, Dominique (2002). "Censuses, identity formation, and the struggle for political power". In Kertzer, David I.; Arel, Dominique (eds.). Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–42.

- ^ "Final recommended questions for the 2011 Census in England and Wales: Ethnic group" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Cornish granted minority status within the UK". Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Nazroo, James (2021-04-09). "A longitudinal Survey of Ethnic Minorities: Focus and Design. Final Report to the ESRC and ONS".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Haug, Werner; Compton, Paul; Courbage, Youssef (2002). The Demographic Characteristics of Immigrant Populations. Council of Europe. ISBN 9789287149749.

- ^ Favell, Adrian (1998). Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in France and Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-17609-9.

- ^ Kymlicka, Will (2007). Multicultural Odysseys: Navigating the New International Politics of Diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-928040-7.

- ^ Panayi, Panikos (2004). "The evolution of multiculturalism in Britain and Germany: An historical survey". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 25 (5/6): 466–480. doi:10.1080/01434630408668919. S2CID 146650540.

- ^ "Race chief wants integration push". BBC News. 3 April 2004. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ a b "So what exactly is multiculturalism?". BBC News. 5 April 2004. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Davis attacks UK multiculturalism". BBC News. 3 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Race, Faith, and UK Policy: a brief history". University of York. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Uberoi, Elise (29 June 2016). European Union Referendum 2016 (PDF). House of Commons.

- ^ "UK majority back multiculturalism". BBC News. 10 August 2005. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Doubting multiculturalism" (PDF). Trend Briefing 1. Ipsos MORI. May 2009. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ ETHNOS Research and Consultancy (November 2005). "Citizenship and belonging: What is Britishness?" (PDF). Commission for Racial Equality. p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Míriam Juan-Torres; Tim Dixon; Arisa Kimaram (October 2020). "Britain's Core Beliefs". Britain's Choice: Common Ground and Division in 2020s Britain (Report). p. 26.

- ^ ETHNOS Research and Consultancy (May 2006). "The decline of Britishness: A research study" (PDF). Commission for Racial Equality. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Fieldhouse, E.; Sobolewska, M. (1 April 2013). "Introduction: Are British Ethnic Minorities Politically Under-represented?". Parliamentary Affairs. 66 (2): 235–245. doi:10.1093/pa/gss089. ISSN 0031-2290.

- ^ a b c d Adolino, Jessica (1998). Ethnic Minorities, Electoral Politics and Political Integration in Britain. London: Pinter. pp. 43–53.

- ^ Eichler, William (October 2017). "Ethnic minorities 'under-represented' in public sector leadership roles, PM says". LocalGov. Archived from the original on 2018-12-06. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ a b Uberoi, Elise (2021). Ethnic diversity in politics and public life (PDF). The House of Commons.

- ^ "Diane Abbott MP". www.dianeabbott.org.uk. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Wood, John; Cracknell, Richard (October 2013). "Ethnic Minorities in Politics, Government and Public Life" (PDF). House of Commons Library. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Audickas, Lukas; Cracknell, Richard (November 2018). "Social background of MPs 1979-2017". House of Commons library. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Lupin, Neil; Tulsiani, Raj (2018). "Local Government Leadership 2018" (PDF). Green Park. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-06. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Scottish Government (2017). "Scotland's Councillors 2017-22" (PDF). Improvement Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b Kettlewell, Kelly; Phillips, Liz (May 2014). "Census of Local Authority Councillors 2013" (PDF). www.nfer.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2018.