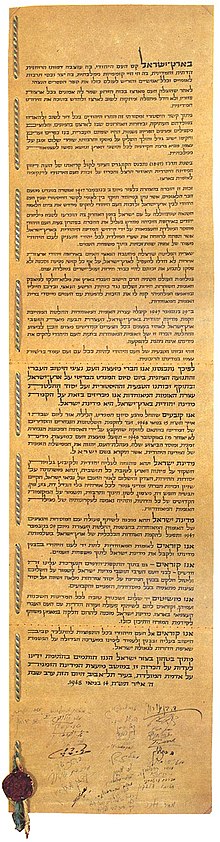

Israeli Declaration of Independence

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel[2] (Hebrew: הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive Head of the World Zionist Organization,[a][3] Chairman of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and later first Prime Minister of Israel.[4] It declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel, which would come into effect on termination of the British Mandate at midnight that day.[5][1] The event is celebrated annually in Israel as Independence Day, a national holiday on 5 Iyar of every year according to the Hebrew calendar.

Background

The possibility of a Jewish homeland in Palestine had been a goal of Zionist organisations since the late 19th century. In 1917 British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour stated in a letter to British Jewish community leader Walter, Lord Rothschild that:

His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.[6]

Through this letter, which became known as the Balfour Declaration, British government policy officially endorsed Zionism. After World War I, the United Kingdom was given a mandate for Palestine, which it had conquered from the Ottomans during the war. In 1937 the Peel Commission suggested partitioning Mandate Palestine into an Arab state and a Jewish state, though the proposal was rejected as unworkable by the government and was at least partially to blame for the renewal of the 1936–39 Arab revolt.

In the face of increasing violence after World War II, the British handed the issue over to the recently established United Nations. The result was Resolution 181(II), a plan to partition Palestine into Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem. The Jewish state was to receive around 56% of the land area of Mandate Palestine, encompassing 82% of the Jewish population, though it would be separated from Jerusalem. The plan was accepted by most of the Jewish population, but rejected by much of the Arab populace. On 29 November 1947, the resolution to recommend to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union was put to a vote in the United Nations General Assembly.[7]

The result was 33 to 13 in favour of the resolution, with 10 abstentions. Resolution 181(II): PART I: Future constitution and government of Palestine: A. TERMINATION OF MANDATE, PARTITION AND INDEPENDENCE: Clause 3 provides:

Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem, ... shall come into existence in Palestine two months after the evacuation of the armed forces of the mandatory Power has been completed but in any case not later than 1 October 1948.

The Arab countries (all of which had opposed the plan) proposed to query the International Court of Justice on the competence of the General Assembly to partition a country, but the resolution was rejected.

Drafting the text

The first draft of the declaration was made by Zvi Berenson, the legal advisor of the Histadrut trade union and later a Justice of the Supreme Court, at the request of Pinchas Rosen. A revised second draft was made by three lawyers, Mordechai Baham, Uri Yadin and Zvi Eli Baker, and was framed by a committee including David Remez, Pinchas Rosen, Haim-Moshe Shapira, Moshe Sharett and Aharon Zisling.[8] A second committee meeting, which included David Ben-Gurion, Yehuda Leib Maimon, Sharett and Zisling produced the final text.[9]

Minhelet HaAm Vote

On 12 May 1948, the Minhelet HaAm (Hebrew: מנהלת העם, lit. People's Administration) was convened to vote on declaring independence.[10][11] Three of the thirteen members were absent, with Yehuda Leib Maimon and Yitzhak Gruenbaum being blocked in besieged Jerusalem, while Yitzhak-Meir Levin was in the United States.

The meeting started at 13:45 and ended after midnight. The decision was between accepting the American proposal for a truce, or declaring independence. The latter option was put to a vote, with six of the ten members present supporting it:

- For: David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Sharett (Mapai); Peretz Bernstein (General Zionists); Haim-Moshe Shapira (Hapoel HaMizrachi); Mordechai Bentov, Aharon Zisling (Mapam).

- Against: Eliezer Kaplan, David Remez (Mapai); Pinchas Rosen (New Aliyah Party); Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit (Sephardim and Oriental Communities).

Chaim Weizmann, the Chairman of the World Zionist Organization,[a] and soon to be first President of Israel, endorsed the decision, after reportedly asking "What are they waiting for, the idiots?"[8]

Final wording

The draft text was submitted for approval to a meeting of Moetzet HaAm at the JNF building in Tel Aviv on 14 May. The meeting started at 13:50 and ended at 15:00, an hour before the declaration was due to be made. Despite ongoing disagreements, members of the Council unanimously voted in favour of the final text. During the process, there were two major debates, centering on the issues of borders and religion.

Borders

The borders were not specified in the Declaration, although its 14th paragraph indicated a readiness to cooperate in the implementation of the UN Partition Plan.[12] The original draft had declared that the borders would be decided by the UN partition plan. While this was supported by Rosen and Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, it was opposed by Ben-Gurion and Zisling, with Ben-Gurion stating, "We accepted the UN Resolution, but the Arabs did not. They are preparing to make war on us. If we defeat them and capture western Galilee or territory on both sides of the road to Jerusalem, these areas will become part of the state. Why should we obligate ourselves to accept boundaries that in any case the Arabs don't accept?"[8] The inclusion of the designation of borders in the text was dropped after the provisional government of Israel, the Minhelet HaAm, voted 5–4 against it.[9] The Revisionists, committed to a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan River (that is, including Transjordan), wanted the phrase "within its historic borders" included, but were unsuccessful.

Religion

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

The second major issue was over the inclusion of God in the last section of the document, with the draft using the phrase "and placing our trust in the Almighty". The two rabbis, Shapira and Yehuda Leib Maimon, argued for its inclusion, saying that it could not be omitted, with Shapira supporting the wording "God of Israel" or "the Almighty and Redeemer of Israel".[8] It was strongly opposed by Zisling, a member of the secularist Mapam. In the end the phrase "Rock of Israel" was used, which could be interpreted as either referring to God, or the land of Eretz Israel, Ben-Gurion saying "Each of us, in his own way, believes in the 'Rock of Israel' as he conceives it. I should like to make one request: Don't let me put this phrase to a vote." Although its use was still opposed by Zisling, the phrase was accepted without a vote.

Name

The writers also had to decide on the name for the new state. Eretz Israel, Ever (from the name Eber), Judea, and Zion were all suggested, as were Ziona, Ivriya and Herzliya.[13] Judea and Zion were rejected because, according to the partition plan, Jerusalem (Zion) and most of the Judaean Mountains would be outside the new state.[14] Ben-Gurion put forward "Israel" and it passed by a vote of 6–3.[15] Official documents released in April 2013 by the State Archive of Israel show that days before the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, officials were still debating about what the new country would be called in Arabic: Palestine (فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Zion (صهيون, Ṣahyūn) or Israel (إسرائيل, ’Isrā’īl). Two assumptions were made: "That an Arab state was about to be established alongside the Jewish one in keeping with the UN's partition resolution the year before, and that the Jewish state would include a large Arab minority whose feelings needed to be taken into account". In the end, the officials rejected the name Palestine because they thought that would be the name of the new Arab state and could cause confusion so they opted for the most straightforward option of Israel.[16]

Other items

At the meeting on 14 May, several other members of Moetzet HaAm suggested additions to the document. Meir Vilner wanted it to denounce the British Mandate and military but Sharett said it was out of place. Meir Argov pushed to mention the Displaced Persons camps in Europe and to guarantee freedom of language. Ben-Gurion agreed with the latter but noted that Hebrew should be the main language of the state.

The debate over wording did not end completely even after the Declaration had been made. Declaration signer Meir David Loewenstein later claimed, "It ignored our sole right to Eretz Israel, which is based on the covenant of the Lord with Abraham, our father, and repeated promises in the Tanach. It ignored the aliya of the Ramban and the students of the Vilna Gaon and the Ba'al Shem Tov, and the [rights of] Jews who lived in the 'Old Yishuv'."[17]

Declaration ceremony

The ceremony was held in the Tel Aviv Museum (today known as Independence Hall) but was not widely publicised as it was feared that the British Authorities might attempt to prevent it or that the Arab armies might invade earlier than expected. An invitation was sent out by messenger on the morning of 14 May telling recipients to arrive at 15:30 and to keep the event a secret. The event started at 16:00 (a time chosen so as not to breach the sabbath) and was broadcast live as the first transmission of the new radio station Kol Yisrael.[18]

The final draft of the declaration was typed at the Jewish National Fund building following its approval earlier in the day. Ze'ev Sherf, who stayed at the building in order to deliver the text, had forgotten to arrange transport for himself. Ultimately, he had to flag down a passing car and ask the driver (who was driving a borrowed car without a licence) to take him to the ceremony. Sherf's request was initially refused but he managed to persuade the driver to take him.[8] The car was stopped by a policeman for speeding while driving across the city though a ticket was not issued after it was explained that he was delaying the declaration of independence.[15] Sherf arrived at the museum at 15:59.[19]

At 16:00, Ben-Gurion opened the ceremony by banging his gavel on the table, prompting a spontaneous rendition of Hatikvah, soon to be Israel's national anthem, from the 250 guests.[15] On the wall behind the podium hung a picture of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, and two flags, later to become the official flag of Israel.

After telling the audience "I shall now read to you the scroll of the Establishment of the State, which has passed its first reading by the National Council", Ben-Gurion proceeded to read out the declaration, taking 16 minutes, ending with the words "Let us accept the Foundation Scroll of the Jewish State by rising" and calling on Rabbi Fishman to recite the Shehecheyanu blessing.[15]

Signatories

As leader of the Yishuv, David Ben-Gurion was the first person to sign. The declaration was due to be signed by all 37 members of Moetzet HaAm. However, twelve members could not attend, with eleven of them trapped in besieged Jerusalem and one abroad. The remaining 25 signatories present were called up in alphabetical order to sign, leaving spaces for those absent. Although a space was left for him between the signatures of Eliyahu Dobkin and Meir Vilner, Zerach Warhaftig signed at the top of the next column, leading to speculation that Vilner's name had been left alone to isolate him, or to stress that even a communist had agreed with the declaration.[15] However, Warhaftig later denied this, stating that a space had been left for him (as he was one of the signatories trapped in Jerusalem) where a Hebraicised form of his name would have fitted alphabetically, but he insisted on signing under his actual name so as to honour his father's memory and so moved down two spaces. He and Vilner would be the last surviving signatories, and remained close for the rest of their lives. Of the signatories, two were women (Golda Meir and Rachel Cohen-Kagan).[20]

When Herzl Rosenblum, a journalist, was called up to sign, Ben-Gurion instructed him to sign under the name Herzl Vardi, his pen name, as he wanted more Hebrew names on the document. Although Rosenblum acquiesced to Ben-Gurion's request and legally changed his name to Vardi, he later admitted to regretting not signing as Rosenblum.[15] Several other signatories later Hebraised their names, including Meir Argov (Grabovsky), Peretz Bernstein (then Fritz Bernstein), Avraham Granot (Granovsky), Avraham Nissan (Katznelson), Moshe Kol (Kolodny), Yehuda Leib Maimon (Fishman), Golda Meir (Meyerson/Myerson), Pinchas Rosen (Felix Rosenblueth) and Moshe Sharett (Shertok). Other signatories added their own touches, including Saadia Kobashi who added the phrase "HaLevy", referring to the tribe of Levi.[20]

After Sharett, the last of the signatories, had put his name to paper, the audience again stood and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra played "Hatikvah". Ben-Gurion concluded the event with the words "The State of Israel is established! This meeting is adjourned!"[15]

Aftermath

| History of Israel |

|---|

|

|

|

The declaration was signed in the context of civil war between the Arab and Jewish populations of the Mandate that had started the day after the partition vote at the UN six months earlier. Neighbouring Arab states and the Arab League were opposed to the vote and had declared they would intervene to prevent its implementation. In a cablegram on 15 May 1948 to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States claimed that "the Arab states find themselves compelled to intervene in order to restore law and order and to check further bloodshed".[21]

Over the next few days after the declaration, armies of Egypt, Trans-Jordan, Iraq, and Syria engaged Israeli troops inside the area of what had just ceased to be Mandatory Palestine, thereby starting the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. A truce began on 11 June, but fighting resumed on 8 July and stopped again on 18 July, before restarting in mid-October and finally ending on 24 July 1949 with the signing of the armistice agreement with Syria. By then Israel had retained its independence and increased its land area by almost 50% compared to the 1947 UN Partition Plan.[22]

Following the declaration, Moetzet HaAm became the Provisional State Council, which acted as the legislative body for the new state until the first elections in January 1949.[23]

Many of the signatories would play a prominent role in Israeli politics following independence; Moshe Sharett and Golda Meir both served as Prime Minister, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi became the country's second president in 1952, and several others served as ministers. David Remez was the first signatory to pass away, dying in May 1951, while Meir Vilner, the youngest signatory at just 29, was the longest living, serving in the Knesset until 1990 and dying in June 2003. Eliyahu Berligne, the oldest signatory at 82, died in 1959.[24]

Eleven minutes after midnight, the United States de facto recognised the State of Israel.[25] This was followed by Iran (which had voted against the UN partition plan), Guatemala, Iceland, Nicaragua, Romania, and Uruguay. The Soviet Union was the first nation to fully recognise Israel de jure on 17 May 1948,[26] followed by Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Ireland, and South Africa.[citation needed] The United States extended official recognition after the first Israeli election, as Truman had promised on 31 January 1949.[27] By virtue of General Assembly Resolution 273 (III), Israel was admitted to membership in the United Nations on 11 May 1949.[28]

In the three years following the 1948 Palestine war, about 700,000 Jews immigrated to Israel, residing mainly along the borders and in former Arab lands.[29] Around 136,000 were some of the 250,000 displaced Jews of World War II.[30] And from the 1948 Arab–Israeli War until the early 1970s, 800,000–1,000,000 Jews left, fled, or were expelled from their homes in Arab countries; 260,000 of them reached Israel between 1948 and 1951; and 600,000 by 1972.[31][32][33]

At the same time, a large number of Arabs left, fled or were expelled from, what became Israel. In the Report of the Technical Committee on Refugees (Submitted to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine in Lausanne on 7 September 1949) – (A/1367/Rev.1), in paragraph 15,[34] the estimate of the statistical expert, which the Committee believed to be as accurate as circumstances permitted, indicated that the number of refugees from Israel-controlled territory amounted to approximately 711,000.[35]

Status in Israeli law

Paragraph 13 of the Declaration provides that the State of Israel would be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex;. However, the Knesset maintains that the declaration is neither a law nor an ordinary legal document.[36] The Supreme Court has ruled that the guarantees were merely guiding principles, and that the declaration is not a constitutional law making a practical ruling on the upholding or nullification of various ordinances and statutes.[37]

In 1994 the Knesset amended two basic laws, Human Dignity and Liberty and Freedom of Occupation, introducing (among other changes) a statement saying "the fundamental human rights in Israel will be honored (...) in the spirit of the principles included in the declaration of the establishment of the State of Israel."

The scroll

Although Ben-Gurion had told the audience that he was reading from the scroll of independence, he was actually reading from handwritten notes because only the bottom part of the scroll had been finished by artist and calligrapher Otte Wallish by the time of the declaration (he did not complete the entire document until June).[17] The scroll, which is bound together in three parts, is generally kept in the country's National Archives.

See also

- Churchill White Paper – 1922 British Policy in Palestine

- 1929 Palestine riots – Arab–Jewish clashes in Mandatory Palestine

- Passfield white paper – 1930 statement of British policy in Palestine

- White Paper of 1939 – British policy paper regarding Palestine

- The Recording of the Israel Declaration of Independence

- Palestinian Declaration of Independence – 1988 statement that formally established the State of Palestine

- Yom Ha'atzmaut – Public holiday

- List of international declarations

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Zionists Proclaim New State of Israel; Truman Recognizes it and Hopes for Peace" New York Times, 15 May 1948

- ^ "The Declaration Scroll". Independence Hall of Israel. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Brenner, Michael; Frisch, Shelley (April 2003). Zionism: A Brief History. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 184.

- ^ "Zionist Leaders: David Ben-Gurion 1886–1973". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Proclamation of Independence". www.knesset.gov.il.

- ^ Yapp, M.E. (1987). The Making of the Modern Near East 1792–1923. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 290. ISBN 0-582-49380-3.

- ^ UNITED NATIONS General Assembly: A/RES/181(II): 29 November 1947: Resolution 181 (II): Future government of Palestine: Retrieved 26 April 2012 Archived 24 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e The State of Israel Declares Independence Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ^ a b Harris, J. (1998) The Israeli Declaration of Independence Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Journal of the Society for Textual Reasoning, Vol. 7

- ^ Tuvia Friling, S. Ilan Troen (1998) "Proclaiming Independence: Five Days in May from Ben-Gurion's Diary" Israel Studies, 3.1, pp. 170–194

- ^ Zeev Maoz, Ben D. Mor (2002) Bound by Struggle: The Strategic Evolution of Enduring International Rivalries, University of Michigan Press, p. 137

- ^ "Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem: Statement of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists" (PDF). 16 February 2024. p. 39. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

The Declaration expressed the State's readiness to cooperate with the UN in implementing Resolution 181(II), calling on the UN to assist with state-building and on the Arab parties waging conflict to "preserve peace" and participate in building the new State with "full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions."

- ^ Gilbert, M. (1998) Israel: A History, London: Doubleday. p. 187. ISBN 0-385-40401-8

- ^ "Why not Judea? Zion? State of the Hebrews?". Haaretz. 7 May 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g One Day that Shook the world Archived 12 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Jerusalem Post, 30 April 1998, by Elli Wohlgelernter

- ^ "Why Israel's first leaders chose not to call the country 'Palestine' in Arabic". The Times of Israel.

- ^ a b Wallish and the Declaration of Independence Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Jerusalem Post, 1998 (republished on Eretz Israel Forever)

- ^ Shelley Kleiman-The State of Israel Declares Independence Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ^ "The throwback museum that echoes independence" Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine St. Louis Jewish Light, 5 December 2012

- ^ a b For this reason we congregated Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Iton Tel Aviv, 23 April 2004

- ^ PDF copy of Cablegram from the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States of the 15 May 1948: Retrieved 13 December 2013 Archived 7 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cragg, Kenneth (1997). Palestine. The Prize and Price of Zion. Cassel. pp. 57, 116. ISBN 978-0-304-70075-2.

- ^ Louvish, Misha (December 30, 2006). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. p. 209. ISBN 9780028659282

- ^ "The Signatories of the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Israel via gov.il. 8 June 2003. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ National Archives Celebrates 60th Anniversary of the State of Israel National Archives, 28 April 2008

- ^ Ian J. Bickerton (2009) The Arab-Israeli Conflict: A History Reaktion Books, p. 79

- ^ Press Release, 31 January 1949. Official File, Truman Papers Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Truman Library

- ^ "United Nations Maintenance Page". unispal.un.org. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, chap. VI.

- ^ Displaced Persons Retrieved 29 October 2007 from the US Holocaust Museum.

- ^ Schwartz, Adi (4 January 2008). "All I Wanted was Justice". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Malka Hillel Shulewitz, The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands, Continuum 2001, pp. 139 and 155.

- ^ Ada Aharoni "The Forced Migration of Jews from Arab Countries" Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Historical Society of Jews from Egypt website. Accessed 1 February 2009.

- ^ "Report of the Technical Committee on Refugees (Submitted to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine in Lausanne on 7 September 1949) – (A/1367/Rev.1)". Archived from the original on 3 June 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the Period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950 Archived 20 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, published by the United Nations Conciliation Commission, 23 October 1950. (U.N. General Assembly Official Records, 5th Session, Supplement No. 18, Document A/1367/Rev. 1)

- ^ The Proclamation of Independence Knesset website

- ^ The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Further reading

- Herf, Jeffrey. 2021. "The U.S. State Department's Opposition to Zionist Aspirations during the Early Cold War: George F. Kennan and George C. Marshall in 1947–1948." Journal of Cold War Studies 23 (4): 153–180.

External links

- Proclamation of Independence: Official Gazette: Number 1; Tel Aviv, 5 Iyar 5708, 14.5.1948 Page 1

- U.S. Recognition of de facto government of Israel. Archived 16 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Signatorius". Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, exhibition held at the Engel Gallery dealing with the independence declaration in Israeli art.

- Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel – English translation of text on the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Afairs website