Eros and Civilization

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Herbert Marcuse |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

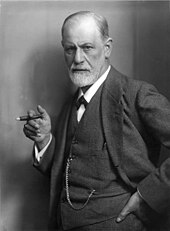

| Subject | Sigmund Freud |

| Publisher | Beacon Press |

Publication date | 1955 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 277 (Beacon Press paperback edition) |

| ISBN | 0-8070-1555-5 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Frankfurt School |

|---|

|

Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (1955; second edition, 1966) is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, and explores the potential of collective memory to be a source of disobedience and revolt and point the way to an alternative future. Its title alludes to Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). The 1966 edition has an added "political preface".

One of Marcuse's best known works, the book brought him international fame. Both Marcuse and many commentators have considered it his most important book, and it was seen by some as an improvement over the previous attempt to synthesize Marxist and psychoanalytic theory by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Eros and Civilization helped shape the subcultures of the 1960s and influenced the gay liberation movement, and with other books on Freud, such as the classicist Norman O. Brown's Life Against Death (1959) and the philosopher Paul Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy (1965), placed Freud at the center of moral and philosophical inquiry. Some have evaluated Eros and Civilization as superior to Life Against Death, while others have found the latter work superior. It has been suggested that Eros and Civilization reveals the influence of the philosopher Martin Heidegger. Marcuse has been credited with offering a convincing critique of neo-Freudianism, but critics have accused him of being utopian in his objectives and of misinterpreting Freud's theories. Critics have also suggested that his objective of synthesizing Marxist and psychoanalytic theory is impossible.

Summary

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2019) |

In the "Political Preface" that opens the work, Marcuse writes that the title Eros and Civilization expresses the optimistic view that the achievements of modern industrial society would make it possible to use society's resources to shape "man's world in accordance with the Life Instincts, in the concerted struggle against the purveyors of Death." He concludes the preface with the words, "Today the fight for life, the fight for Eros, is the political fight."[1] Marcuse questions the view of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, that "civilization is based on the permanent subjugation of the human instincts". He discusses the social meaning of biology — history seen not as a class struggle, but a fight against repression of our instincts. He argues that "advanced industrial society" (modern capitalism) is preventing us from reaching a non-repressive society "based on a fundamentally different experience of being, a fundamentally different relation between man and nature, and fundamentally different existential relations".[2]

Marcuse also discusses the views of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller,[3] and criticizes the psychiatrist Carl Jung, whose psychology he describes as an "obscurantist neo-mythology". He also criticizes neo-Freudians like Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan, and Clara Thompson.[4]

Publication history

[edit]Eros and Civilization was first published in 1955 by Beacon Press. In 1974, it was published as a Beacon Paperback.[5]

Reception

[edit]Mainstream media

[edit]Eros and Civilization received positive reviews from the philosopher Abraham Edel in The Nation and the historian of science Robert M. Young in the New Statesman.[6][7] The book was also reviewed by the anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn in The New York Times Book Review and discussed by Susan Sontag in The Supplement to the Columbia Spectator.[8][9] Later discussions include those in Choice by H. N. Tuttle,[10] R. J. Howell,[11] and M. A. Bertman.[12] The art critic Roger Kimball discussed the book in The New Criterion.[13]

Edel credited Marcuse with distinguishing between what portion of the burden repressive civilization places on the fundamental drives is made necessary by survival needs and what serves the interests of domination and is now unnecessary because of the advanced science of the modern world, and with suggesting what changes in cultural attitudes would result from relaxation of the repressive outlook.[6] Young called the book important and honest, as well as "serious, highly sophisticated and elegant". He wrote that Marcuse's conclusions about "surplus repression" converted Freud into an "eroticised Marx", and credited Marcuse with convincingly criticizing the neo-Freudians Fromm, Horney, and Sullivan. Though maintaining that both they and Marcuse confused "ideology with reality" and minimized "the biological sphere", he welcomed Marcuse's view that "the distinction between psychological and political categories has been made obsolete by the condition of man in the present era."[7] Sontag wrote that together with Brown's Life Against Death (1959), Eros and Civilization represented a "new seriousness about Freudian ideas" and exposed most previous writing on Freud in the United States as irrelevant or superficial.[9]

Tuttle suggested that Eros and Civilization could not be properly understood without reading Marcuse's earlier work Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity (1932).[10] Howell wrote that the book had been improved upon by C. Fred Alford's Melanie Klein and Critical Social Theory (1989).[11] Bertman wrote that Eros and Civilization was exciting and helped make Marcuse influential.[12] Kimball identified Eros and Civilization and One-Dimensional Man (1964) as Marcuse's most influential books, and wrote that Marcuse's views parallel those of Norman O. Brown, despite the difference of tone between the two thinkers. He dismissed the ideas of both Marcuse and Brown as false and harmful.[13]

Socialist publications

[edit]Eros and Civilization received a mixed review from the Marxist writer Paul Mattick in Western Socialist.[14] The book was also discussed by Stephen J. Whitfield in Dissent.[15]

Mattick credited Marcuse with renewing "the endeavor to read Marx into Freud", following the unsuccessful attempts of Wilhelm Reich, and agreed with Marcuse that Freudian revisionism is "reformist or non-revolutionary". However, he wrote that Freud would have been surprised at the way Marcuse read revolutionary implications into his theories. He noted that Marcuse's way of overcoming the dilemma that "a full satisfaction of man’s instinctual needs is incompatible with the existence of civilized society" was Marxist, despite the fact that Marcuse nowhere mentioned Marx and referred to capitalism only indirectly, as "industrial civilization". He argued that Marcuse tried to develop ideas that were already present in "the far less ambiguous language of Marxian theory", but still welcomed the fact that Marcuse made psychoanalysis and dialectical materialism reach the same desired result. However, he concluded that Marcuse's "call to opposition to present-day conditions remains a mere philosophical exercise without applicability to social actions."[14]

Whitfield noted that Marcuse considered Eros and Civilization his most important book, and wrote that it "merits consideration as his best, neither obviously dated nor vexingly inaccessible" and that it "was honorable of Marcuse to try to imagine how the fullest expression of personality, or plenitude, might extinguish the misery that was long deemed an essential feature of the human condition." He considered the book "thrilling to read" because of Marcuse's conjectures about "how the formation of a life without material restraints might somehow be made meaningful." He argued that Marcuse's view that technology could be used to create a utopia was not consistent with his rejection of "technocratic bureaucracy" in his subsequent work One-Dimensional Man. He also suggested that it was the work that led Pope Paul VI to publicly condemn Marcuse in 1969.[15]

Reviews in academic journals

[edit]Eros and Civilization received positive reviews from the psychoanalyst Martin Grotjahn in The Psychoanalytic Quarterly,[16] Paul Nyberg in the Harvard Educational Review,[17] and Richard M. Jones in American Imago,[18] and a negative review from the philosopher Herbert Fingarette in The Review of Metaphysics.[19] In the American Journal of Sociology, the book received a positive review from the sociologist Kurt Heinrich Wolff and later a mixed review from an author using the pen-name "Barbara Celarent".[20][21][22] The book was also discussed by Margaret Cerullo in New German Critique.[23]

Grotjahn described the book as a "sincere and serious" philosophical critique of psychoanalysis, adding that it was both well-written and fascinating. He credited Marcuse with developing "logically and psychologically the instinctual dynamic trends leading to the utopia of a nonrepressive civilization" and demonstrating that "true freedom is not possible in reality today", being reserved for "fantasies, dreams, and the experiences of art." However, he suggested that Marcuse might be "mistaken in the narrowness of his concept of basic, or primary, repression".[16] Nyberg described the book as "brilliant", "moving", and "extraordinary", concluding that it was, "perhaps the most important work on psychoanalytic theory to have appeared in a very long time."[17] Jones praised Marcuse's interpretation of psychoanalysis; he also maintained that Marcuse, despite not being a psychoanalyst, had understood psychoanalytic theory and shown how it could be improved upon. However, he believed Marcuse left some questions unresolved.[18]

Fingarette considered Marcuse the first to develop the idea of a utopian society free from sexual repression into a systematic philosophy. However, he noted that he used the term "repression" in a fashion that drastically changed its meaning compared to "strict psychoanalytic usage", employing it to refer to "suppression, sublimation, repression proper, and restraint". He also questioned the accuracy of Marcuse's understanding of Freud, arguing that he was actually presenting "analyses and conclusions already worked out and accepted by Freud". He also questioned whether his concept of "sensuous rationality" was original, and criticized him for failing to provide sufficient discussion of the Oedipus complex. He concluded that he put forward an inadequate "one-dimensional, instinctual view of man" and that his proposed non-repressive society was a "fantasy-Utopia".[19]

Wolff considered the book a great work. He praised the "magnificent" scope of Eros and Civilization and Marcuse's "inspiring" sense of dedication. He noted that the book could be criticized for Marcuse's failure to answer certain questions and for some "omissions and obscurities", but considered these points to be "of minor importance."[20] Celarent considered Eros and Civilization a "deeper book" than One-Dimensional Man (1964) because it "addressed the core issue: How should we live?" However, Celarent wrote that Marcuse's decision to analyze the issue of what should be done with society's resources with reference to Freud's writings "perhaps curtailed the lifetime of his book, for Freud dropped quickly from the American intellectual scene after the 1970s, just as Marcuse reached his reputational peak." Celarent identified Marx's Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867–1883) as a source of Marcuse's views on production and labor markets, and described his "combination of Marx and Freud" as "very clever". Celarent credited Marcuse with using psychoanalysis to transform Marx's concept of alienation into "a more subtle psychological construct", the "performance principle". In Celarent's view, it anticipated arguments later made by the philosopher Michel Foucault, but with "a far more plausible historical mechanism" than Foucault's "nebulous" concept of discourse. However, Celarent considered Marcuse's chapter giving "proper Freudian reasons for the historicity of the reality principle" to be of historical interest only, and wrote that Marcuse proposed a "shadowy utopia". Celarent suggested that Eros and Civilization had commonly been misinterpreted, and that Marcuse was not concerned with advocating "free love and esoteric sexual positions."[21]

Discussions in Theory & Society

[edit]Discussions of the work in Theory & Society include those by the philosopher and historian Martin Jay,[24] the psychoanalyst Nancy Chodorow,[25] and C. Fred Alford.[26]

Jay described the book as one of Marcuse's major works, and his "most utopian" book. He maintained that it completed Marcuse's "theory of remembrance", according to which "memory subverts one-dimensional consciousness and opens up the possibility of an alternative future", and helped Marcuse advance a form of critical theory no longer able to rely on revolutionary proletariat. However, he criticized Marcuse's theory for its "undefined identification of individual and collective memory", writing that Marcuse failed to explain how the individual was in "archaic identity with the species". He suggested that there might be an affinity between Marcuse's views and Jung's, despite Marcuse's contempt for Jung. He criticized Marcuse for his failure to undertake experiments in personal recollection such as those performed by the philosopher Walter Benjamin, or to rigorously investigate the differences between personal memory of an actual event in a person's life and collective historical memory of events antedating all living persons. Jay suggested that the views of the philosopher Ernst Bloch might be superior to Marcuse's, since they did more to account for "the new in history" and more carefully avoided equating recollection with repetition.[24]

Chodorow considered the work of Marcuse and Brown important and maintained that it helped suggest a better psychoanalytic social theory. However, she questioned their interpretations of Freud, argued that they see social relations as an unnecessary form of constraint and fail to explain how social bonds and political activity are possible, criticized their view of "women, gender relations, and generation", and maintained that their use of primary narcissism as a model for union with others involves too much concern with individual gratification. She argued that Eros and Civilization shows some of the same features that Marcuse criticized in Brown's Love's Body (1966), that the form of psychoanalytic theory Marcuse endorsed undermines his social analysis, and that in his distinction between surplus and basic repression, Marcuse did not evaluate what the full effects of the latter might be in a society without domination. She praised parts of the work, such as his chapter on "The Transformation of Sexuality into Eros", but maintained that in some ways it conflicted with Marcuse's Marxism. She criticized Marcuse's account of repression, noting that he used the term in a "metaphoric" fashion that eliminated the distinction between the conscious and the unconscious, and argued that his "conception of instinctual malleability" conflicted with his proposal for a "new reality principle" based on the drives and made his critique of Fromm and neo-Freudianism disingenuous, and that Marcuse "simply asserted a correspondence between society and personality organization".[25]

Alford, writing in 1987, noted that Marcuse, like many of his critics, regarded Eros and Civilization as his most important work, but observed that Marcuse's views have been criticized for being both too similar and too different to those of Freud. He wrote that recent scholarship broadly agreed with Marcuse that social changes since Freud's era have changed the character of psychopathology, for example by increasing the number of narcissistic personality disorders. He credited Marcuse with showing that narcissism is a "potentially emancipatory force", but argued that while Marcuse anticipated some subsequent developments in the theory of narcissism, they nevertheless made it necessary to reevaluate Marcuse's views. He maintained that Marcuse misinterpreted Freud's views on sublimation and noted that aspects of Marcuse's "erotic utopia" seem regressive or infantile, as they involved instinctual gratification for its own sake. Though agreeing with Chodorow that this aspect of Marcuse's work is related to his "embrace of narcissism", he denied that narcissism serves only regressive needs, and argued that "its regressive potential may be transformed into the ground of mature autonomy, which recognizes the rights and needs of others." He agreed with Marcuse that "in spite of the reified power of the reality principle, humanity aims at a utopia in which its most fundamental needs would be fulfilled."[26]

Discussions in other journals

[edit]Other discussions of the work include those by the philosopher Jeremy Shearmur in Philosophy of the Social Sciences,[27] the philosopher Timothy F. Murphy in the Journal of Homosexuality,[28] C. Fred Alford in Theory, Culture & Society,[29] Michael Beard in Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures,[30] Peter M. R. Stirk in the History of the Human Sciences,[31] Silke-Maria Weineck in The German Quarterly,[32] Joshua Rayman in Telos,[33] Daniel Cho in Policy Futures in Education,[34] Duston Moore in the Journal of Classical Sociology,[35] Sean Noah Walsh in Crime, Media, Culture,[36] the philosopher Espen Hammer in Philosophy & Social Criticism,[37] the historian Sara M. Evans in The American Historical Review,[38] Molly Hite in Contemporary Literature,[39] Nancy J. Holland in Hypatia,[40] Franco Fernandes and Sérgio Augusto in DoisPontos,[41] and Pieter Duvenage in Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe.[42] In Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie, the book was discussed by Shierry Weber Nicholsen and Kerstin Stakemeier.[43][44] In 2013, it was discussed in Radical Philosophy Review.[45] It received a joint discussion from Arnold L. Farr, the philosopher Douglas Kellner, Andrew T. Lamas, and Charles Reitz,[46] and additional discussions from Stefan Bird-Pollan and Lucio Angelo Privitello.[47][48] The Radical Philosophy Review also reproduced a document from Marcuse, responding to criticism from the Marxist scholar Sidney Lipshires.[49] In 2017, Eros and Civilization was discussed again in the Radical Philosophy Review by Jeffrey L. Nicholas.[50]

Shearmur identified the historian Russell Jacoby's criticism of psychoanalytic "revisionism" in his work Social Amnesia (1975) as a reworking of Marcuse's criticism of neo-Freudianism.[27] Murphy criticized Marcuse for failing to examine Freud's idea of bisexuality.[28] Alford criticized the Frankfurt School for ignoring the work of the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein despite the fact that Klein published a seminal paper two years before the publication of Eros and Civilization.[29] Beard described the book as an "apocalyptic companion" to Life Against Death, and wrote that between them the books provided "one of the most influential blueprints for radical thinking in the decade which followed."[30] Stirk argued that Marcuse's views were a utopian theory with widespread appeal, but that examination of Marcuse's interpretations of Kant, Schiller, and Freud showed that they were based on a flawed methodology. He also maintained that Marcuse's misinterpretation of Freud's concept of reason undermined Marcuse's argument, which privileged a confused concept of instinct over an ambiguous sense of reason.[31] Weineck credited Marcuse with anticipating later reactions to Freud in the 1960s, which maintained in opposition to Freud that the "sacrifice of libido" is not necessary for civilized progress, though she considered Marcuse's views more nuanced than such later ideas. She endorsed Marcuse's criticisms of Fromm and Horney, but maintained that Marcuse underestimated the force of Freud's pessimism and neglected Freud's Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920).[32]

Cho compared Marcuse's views to those of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, writing that the similarities between them were less well known than the differences.[34] Moore wrote that while the influence of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead on Marcuse has received insufficient attention, essential aspects of Marcuse's theory can be "better understood and appreciated when their Whiteheadian origins are examined."[35] Holland discussed Marcuse's ideas in relation to those of the cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin, in order to explore the social and psychological mechanisms behind the "sex/gender system" and to open "new avenues of analysis and liberatory praxis based on these authors' applications of Marxist insights to cultural interpretations" of Freud's writings.[40] Hammer argued that Marcuse was "incapable of offering an account of the empirical dynamics that may lead to the social change he envisions, and that his appeal to the benefits of automatism is blind to its negative effects" and that his "vision of the good life as centered on libidinal self-realization" threatens the freedom of individuals and would "potentially undermine their sense of self-integrity." Hammer maintained that, unlike the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, Marcuse failed to "take temporality and transience properly into account" and had "no genuine appreciation of the need for mourning." He also argued that "political action requires a stronger ego-formation" than allowed for by Marcuse's views.[37] Evans identified Eros and Civilization as an influence on 1960s activists and young people.[38]

Hite identified the book as an influence on Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow (1973), finding this apparent in Pynchon's characterization of Orpheus as a figure connected with music, memory, play, and desire. She added that while Marcuse did not "appeal to mind-altering drugs as adjuncts to phantasy", many of his readers were "happy to infer a recommendation." She argued that while Marcuse does not mention pedophilia, it fits his argument that perverse sex can be "revelatory or demystifying, because it returns experience to the physical body".[39] Duvenage described the book as "fascinating", but wrote that Marcuse's suggestions for a repression-free society have been criticized by the philosopher Marinus Schoeman.[42] Farr, Kellner, Lamas, and Reitz wrote that partly because of the impact of Eros and Civilization, Marcuse's work influenced several academic disciplines in the United States and in other countries.[46] Privitello argued that the chapter on "The Aesthetic Dimension" had pedagogical value. However, he criticized Marcuse for relying on an outdated 19th-century translation of Schiller.[48] Nicholas endorsed Marcuse's "analysis of technological rationality, aesthetic reason, phantasy, and imagination."[50]

Other evaluations, 1955–1986

[edit]Brown commended Eros and Civilization as the first book, following the work of Reich, to "reopen the possibility of the abolition of repression".[51] The philosopher Paul Ricœur compared his philosophical approach to Freud in Freud and Philosophy (1965) to that of Marcuse in Eros and Civilization.[52] Paul Robinson credited Marcuse and Brown with systematically analyzing psychoanalytic theory in order to reveal its critical implications. He believed they went beyond Reich and the anthropologist Géza Róheim in probing the dialectical subtleties of Freud's thought, thereby reaching conclusions more extreme and utopian than theirs. He found Lionel Trilling's work on Freud, Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture (1955), of lesser value. He saw Brown's exploration of the radical implications of psychoanalysis as in some ways more rigorous and systematic than that of Marcuse. He noted that Eros and Civilization has often been compared to Life Against Death, but suggested that it was less elegantly written. He concluded that while Marcuse's work is psychologically less radical than that of Brown, it is politically bolder, and unlike Brown's, succeeded in transforming psychoanalytic theory into historical and political categories. He deemed Marcuse a finer theorist than Brown, believing that he provided a more substantial treatment of Freud.[53]

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre criticized Marcuse for focusing on Freud's metapsychology rather than on psychoanalysis as a method of therapy. He believed that Marcuse followed speculations that were difficult to either support or refute, that his discussion of sex was pompous, that he failed to explain how people whose sexuality was unrepressed would behave, and uncritically accepted Freudian views of sexuality and failed to conduct his own research into the topic. He criticized him for his dismissive treatment of rival theories, such as those of Reich. He also suggested that Marcuse's goal of reconciling Freudian with Marxist theories might be impossible, and, comparing his views to those of the philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, argued that by returning to the themes of the Young Hegelian movement Marcuse had retreated to a "pre-Marxist" perspective.[54]

Phil Brown criticized Marcuse's attempt to "synthesize Marx and Freud", arguing that such a synthesis is impossible. He maintained that Marcuse neglected politics, disregarded the class struggle, advocated "sublimation of human spontaneity and creativity", and failed to criticize the underlying assumptions of Freudian thinking.[55] The gay rights activist Dennis Altman followed Robinson in criticizing Marcuse for failing to clarify "whether sexual repression causes economic subordination or vice versa" or to "connect his use of Freud's image of the primal crime with his ideas about the repression of nongenital and homosexual drives". Though influenced by Marcuse, he commented that Eros and Civilization was referred to surprisingly rarely in gay liberation literature. In an afterword to the 1993 edition of the book, he added that Marcuse's "radical Freudianism" was "now largely forgotten" and had never been "particularly popular in the gay movement."[56]

The social psychologist Liam Hudson suggested that Life Against Death was neglected by radicals because its publication coincided with that of Eros and Civilization. Comparing the two works, he found Eros and Civilization more reductively political and less stimulating.[57] The critic Frederick Crews argued that Marcuse's proposed liberation of instinct was not a real challenge to the status quo, since, by taking the position that such a liberation could only be attempted "after culture has done its work and created the mankind and the world that could be free", Marcuse was accommodating society's institutions. He accused Marcuse of sentimentalism.[58] The psychoanalyst Joel Kovel described Eros and Civilization as more successful than Life Against Death.[59] The psychotherapist Joel D. Hencken described Eros and Civilization as an important example of the intellectual influence of psychoanalysis and an "interesting precursor" to a study of psychology of the "internalization of oppression". However, he believed that aspects of the work have limited its audience.[60]

Myriam Malinovich considered Marcuse's earlier Young Hegelian writings more representative of his actual thinking than Eros and Civilization. She concluded that all the esoteric Fruedian theory and endorsements of libertine sexual behavior were ultimately meant only to colorfully illustrate what Marcuse had previously written about concerning the alienating force of the Power Principle.[61]

Kellner compared Eros and Civilization to Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy and the philosopher Jürgen Habermas's Knowledge and Human Interests (1968). However, he suggested that Ricœur and Habermas made better use of several Freudian ideas.[62] The sociologist Jeffrey Weeks criticized Marcuse as "essentialist" in Sexuality and Its Discontents (1985). Though granting that Marcuse proposed a "powerful image of a transformed sexuality" that had a major influence on post-1960s sexual politics, he considered Marcuse's vision "utopian".[63]

The philosopher Jeffrey Abramson credited Marcuse with revealing the "bleakness of social life" to him and forcing him to wonder why progress does "so little to end human misery and destructiveness". He compared Eros and Civilization to Brown's Life Against Death, the cultural critic Philip Rieff's Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), Ricœur's Freud and Philosophy, and Habermas's Knowledge and Human Interests, writing that these works jointly placed Freud at the center of moral and philosophical inquiry. However, he argued that while Marcuse recognized the difficulties of explaining how sublimation could be compatible with a new and non-repressive social order, he presented a confused account of a "sublimation without desexualization" that could make this possible. He described some of Marcuse's speculations as bizarre, and suggested that Marcuse's "vision of Eros" is "imbalanced in the direction of the sublime" and that the "essential conservatism" of his stance on sexuality had gone unnoticed.[64]

The philosopher Roger Scruton criticized Marcuse and Brown, describing their proposals for sexual liberation as "another expression of the alienation" they condemned.[65] The anthropologist Pat Caplan identified Eros and Civilization as an influence on student protest movements of the 1960s, apparent in their use of the slogan, "Make love not war".[66] Victor J. Seidler credited Marcuse with showing that the repressive organizations of the instincts described by Freud are not inherent in their nature but emerge from specific historical conditions. He contrasted Marcuse's views with Foucault's.[67]

Other evaluations, 1987–present

[edit]The philosopher Seyla Benhabib argued that Eros and Civilization continues the interest in historicity present in Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity and that Marcuse views the sources of disobedience and revolt as being rooted in collective memory.[68] Stephen Frosh found Eros and Civilization and Life Against Death to be among the most important advances towards a psychoanalytic theory of art and culture. However, he considered the way these works turn the internal psychological process of repression into a model for social existence as a whole to be disputable.[69] The philosopher Richard J. Bernstein described Eros and Civilization as "perverse, wild, phantasmal and surrealistic" and "strangely Hegelian and anti-Hegelian, Marxist and anti-Marxist, Nietzschean and anti-Nietzschean", and praised Marcuse's discussion of the theme of "negativity".[70] Edward Hyman suggested that Marcuse's failure to state clearly that his hypothesis is the "primacy of Eros" undermined his arguments and that Marcuse gave an insufficiently through consideration of metapsychology.[71]

Kenneth Lewes endorsed Marcuse's criticism of the "pseudohumane moralizing" of neo-Freudians such as Fromm, Horney, Sullivan, and Thompson.[72] Joel Schwartz identified Eros and Civilization as "one of the most influential Freudian works written since Freud's death". However, he argued that Marcuse failed to reinterpret Freud in a way that adds political to psychoanalytic insights or remedy Freud's "failure to differentiate among various kinds of civil society", instead simply grouping all existing regimes as "repressive societies" and contrasting them with a hypothetical future non-repressive society.[73] Kovel noted that Marcuse studied with Heidegger but later broke with him for political reasons and suggested that the Heideggerian aspects of Marcuse's thinking, which had been in eclipse during Marcuse's most active period with the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, reemerged, displaced onto Freud, in Eros and Civilization.[74]

The economist Richard Posner maintained that Eros and Civilization contains "political and economic absurdities" but also interesting observations about sex and art. He credited Marcuse with providing a critique of conventional sexual morality superior to the philosopher Bertrand Russell's Marriage and Morals (1929), but accused Marcuse of wrongly believing that polymorphous perversity would help to create a utopia and that sex has the potential to be a politically subversive force. He considered Marcuse's argument that capitalism has the ability to neutralize the subversive potential of "forces such as sex and art" interesting, though clearly true only in the case of art. He argued that while Marcuse believed that American popular culture had trivialized sexual love, sex had not had a subversive effect in societies not dominated by American popular culture.[75] The historian Arthur Marwick identified Eros and Civilization as the book with which Marcuse achieved international fame, a key work in the intellectual legacy of the 1950s, and an influence on the subcultures of the 1960s.[76] The historian Roy Porter argued that Marcuse's view that "industrialization demanded erotic austerity" was not original, and was discredited by Foucault in The History of Sexuality (1976).[77]

The philosopher Todd Dufresne compared Eros and Civilization to Brown's Life Against Death and the anarchist author Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd (1960). He questioned to what extent Marcuse's readers understood his work, suggesting that many student activists might have shared the view of Morris Dickstein, to whom it work meant, "not some ontological breakthrough for human nature, but probably just plain fucking, lots of it".[78] Anthony Elliott identified Eros and Civilization as a "seminal" work.[79] The essayist Jay Cantor described Life Against Death and Eros and Civilization as "equally profound".[80]

The philosopher James Bohman wrote that Eros and Civilization "comes closer to presenting a positive conception of reason and Enlightenment than any other work of the Frankfurt School."[81] The historian Dagmar Herzog wrote that Eros and Civilization was, along with Life Against Death, one of the most notable examples of an effort to "use psychoanalytic ideas for culturally subversive and emancipatory purposes". However, she believed that Marcuse's influence on historians contributed to the acceptance of the mistaken idea that Horney was responsible for the "desexualization of psychoanalysis."[82] The critic Camille Paglia wrote that while Eros and Civilization was "one of the centerpieces of the Frankfurt School", she found the book inferior to Life Against Death. She described Eros and Civilization as "overschematic yet blobby and imprecise".[83]

Other views

[edit]The gay rights activist Jearld Moldenhauer discussed Marcuse's views in The Body Politic. He suggested that Marcuse found the gay liberation movement insignificant, and criticized Marcuse for ignoring it in Counterrevolution and Revolt (1972), even though many gay activists had been influenced by Eros and Civilization. He pointed to Altman as an activist who had been inspired by the book, which inspired him to argue that the challenge to "conventional norms" represented by gay people made them revolutionary.[84] Rainer Funk wrote in Erich Fromm: His Life and Ideas (2000) that Fromm, in a letter to the philosopher Raya Dunayevskaya, dismissed Eros and Civilization as an incompetent distortion of Freud and "the expression of an alienation and despair masquerading as radicalism" and referred to Marcuse's "ideas for the future man" as irrational and sickening.[85]

The gay rights activist Jeffrey Escoffier discussed Eros and Civilization in GLBTQ Social Sciences, writing that it "played an influential role in the writing of early proponents of gay liberation", such as Altman and Martin Duberman, and "influenced radical gay groups such as the Gay Liberation Front's Red Butterfly Collective", which adopted as its motto the final line from the "Political Preface" of the 1966 edition of the book: "Today the fight for life, the fight for Eros, is the political fight." Escoffier noted, however, that Marcuse later had misgivings about sexual liberation as it developed in the United States, and that Marcuse's influence on the gay movement declined as it embraced identity politics.[86]

According to P. D. Casteel, Eros and Civilization is, with One-Dimensional Man, the work Marcuse is best known for.[87]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Marcuse 1974, pp. xi, xxv.

- ^ Marcuse 1974, pp. 3, 5.

- ^ Marcuse 1974, p. 182.

- ^ Marcuse 1974, pp. 147, 192, 239, 248.

- ^ Marcuse 1974, p. iv.

- ^ a b Edel 1956, p. 22.

- ^ a b Young 1969, pp. 666–667.

- ^ Kluckhohn 1955, p. 30.

- ^ a b Sontag 1990, pp. ix, 256–262.

- ^ a b Tuttle 1988, p. 1568.

- ^ a b Howell 1990, p. 1398.

- ^ a b Bertman 1998, p. 702.

- ^ a b Kimball 1997, pp. 4–9.

- ^ a b Mattick 1956.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2014, pp. 102–107.

- ^ a b Grotjahn 1956, pp. 429–431.

- ^ a b Nyberg 1956, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Jones 1958, pp. 175–180.

- ^ a b Fingarette 1957, pp. 660–665.

- ^ a b Wolff 1956, pp. 342–343.

- ^ a b Celarent 2010, pp. 1964–1972.

- ^ Sica 2011, pp. 385–387.

- ^ Cerullo 1979, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Jay 1982, pp. 1–15.

- ^ a b Chodorow 1985, pp. 271–319.

- ^ a b Alford 1987, pp. 869–890.

- ^ a b Shearmur 1983, p. 87.

- ^ a b Murphy 1985, pp. 65–77.

- ^ a b Alford 1993, pp. 207–227.

- ^ a b Beard 1998, p. 161.

- ^ a b Stirk 1999, p. 73.

- ^ a b Weineck 2000, pp. 351–365.

- ^ Rayman 2005, pp. 167–187.

- ^ a b Cho 2006, pp. 18–30.

- ^ a b Moore 2007, pp. 83–108.

- ^ Walsh 2008, pp. 221–236.

- ^ a b Hammer 2008, pp. 1071–1093.

- ^ a b Evans 2009, pp. 331–347.

- ^ a b Hite 2010, pp. 677–702.

- ^ a b Holland 2011, pp. 65–78.

- ^ Fernandes & Augusto 2016, pp. 117–123.

- ^ a b Duvenage 2017, pp. 7–21.

- ^ Nicholsen 2006, pp. 164–179.

- ^ Stakemeier 2006, pp. 180–195.

- ^ Radical Philosophy Review 2013, pp. 31–47.

- ^ a b Farr et al. 2013, pp. 1–15.

- ^ Bird-Pollan 2013, pp. 99–107.

- ^ a b Privitello 2013, pp. 109–122.

- ^ Marcuse 2013, pp. 25–30.

- ^ a b Nicholas 2017, pp. 185–213.

- ^ Brown 1985, p. xx.

- ^ Ricœur 1970, p. xii.

- ^ Robinson 1990, pp. 148–149, 223, 224, 231–233.

- ^ MacIntyre 1970, pp. 41–54.

- ^ Brown 1974, pp. 71–72, 75–76.

- ^ Altman 2012, pp. 88, 253.

- ^ Hudson 1976, p. 75.

- ^ Crews 1975, p. 22.

- ^ Kovel 1981, p. 272.

- ^ Hencken 1982, pp. 127, 138, 147, 414.

- ^ Malinovich, Myriam Miedzian. "On Herbert Marcuse and the Concept of Psychological Freedom". Social Research. 49 (1). Johns Hopkins University Press: 158–180.

- ^ Kellner 1984, pp. 193, 195, 434.

- ^ Weeks 1993, pp. 165, 167.

- ^ Abramson 1986, pp. ix, 96–97, 148.

- ^ Scruton 1994, pp. 350, 413.

- ^ Caplan 1987, pp. 6, 27.

- ^ Seidler 1987, p. 95.

- ^ Benhabib 1987, pp. xxx, xxxiii–xxxiv.

- ^ Frosh 1987, pp. 21–22, 150.

- ^ Bernstein 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Hyman 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Lewes 1988, p. 142.

- ^ Schwartz 1990, p. 526.

- ^ Kovel 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Posner 1992, pp. 22–23, 237–240.

- ^ Marwick 1998, p. 291.

- ^ Porter 1996, p. 252.

- ^ Dufresne 2000, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Elliott 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Cantor 2009, p. xii.

- ^ Bohman 2017, p. 631.

- ^ Herzog 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Paglia 2018, p. 421.

- ^ Moldenhauer 1972, p. 9.

- ^ Funk 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Escoffier 2015, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Casteel 2017, pp. 1–6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Books

- Abramson, Jeffrey B. (1986). Liberation and Its Limits: The Moral and Political Thought of Freud. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2913-8.

- Altman, Dennis (2012). Homosexual: Oppression & Liberation. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-4937-2.

- Benhabib, Seyla (1987). "Translator's Introduction". Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13221-3.

- Bernstein, Richard J. (1988). "Negativity: Theme and Variations". In Pippin, Robert; Feenberg, Andrew; Webel, Charles P. (eds.). Marcuse: Critical Theory and the Promise of Utopia. London: Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-44101-5.

- Bohman, James (2017). "Marcuse, Herbert". In Audi, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Third Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-64379-6.

- Brown, Norman O. (1985). Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History. Hanover, New Hampshire: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6144-2.

- Brown, Phil (1974). Toward a Marxist Psychology. New York: Harper Colophon Books.

- Cantor, Jay (2009). "Introduction". In Neu, Jerome (ed.). The Challenge of Islam: The Prophetic Tradition. Santa Cruz: New Pacific Press. ISBN 978-1-55643-802-8.

- Caplan, Pat (1987). "Introduction". In Caplan, Pat (ed.). The Cultural Construction of Sexuality. London: Tavistock Publications. ISBN 978-0-422-60880-0.

- Crews, Frederick (1975). Out of My System: Psychoanalysis, Ideology, and Critical Method. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-501947-6.

- Dufresne, Todd (2000). Tales from the Freudian Crypt: The Death Drive in Text and Context. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3885-9.

- Elliott, Anthony (2002). Psychoanalytic Theory: An Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-91912-5.

- Frosh, Stephen (1987). The Politics of Psychoanalysis: An Introduction to Freudian and Post-Freudian Theory. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-39613-1.

- Funk, Rainer (2000). Erich Fromm: His Life and Ideas. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1224-9.

- Hencken, Joel D. (1982). "Homosexuality and Psychoanalysis: Toward a Mutual Understanding". In Paul, William; Weinrich, James D.; Gonsiorek, John C.; Hotvedt, Mary E. (eds.). Homosexuality: Social, Psychological, and Biological Issues. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-262-13221-3.

- Herzog, Dagmar (2017). Cold War Freud: Psychoanalysis in an Age of Catastrophes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-42087-8.

- Hudson, Liam (1976). The Cult of the Fact. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-01221-8.

- Hyman, Edward (1988). "Eros and Freedom: The Critical Psychology of Herbert Marcuse". In Pippin, Robert; Feenberg, Andrew; Webel, Charles P. (eds.). Marcuse: Critical Theory and the Promise of Utopia. London: Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-44101-5.

- Kellner, Douglas (1984). Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-36830-4.

- Kovel, Joel (1991). History and Spirit: An Inquiry into the Philosophy of Liberation. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2916-9.

- Kovel, Joel (1981). The Age of Desire: Case Histories of a Radical Psychoanalyst. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50818-4.

- Lewes, Kenneth (1988). The Psychoanalytic Theory of Male Homosexuality. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-452-01003-1.

- MacIntyre, Alasdair (1970). Marcuse. London: Fontana.

- Marcuse, Herbert (1974). Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-1555-1.

- Marwick, Arthur (1998). The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States c.1958-c.1974. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-210022-1.

- Murphy, Timothy F. (1985). "Freud Reconsidered: Bisexuality, Homosexuality, and Moral Judgement". In DeCecco, John P.; Shively, Michael G. (eds.). Origins of Sexuality and Homosexuality. New York: Harrington Park Press. ISBN 978-0-918393-00-5.

- Paglia, Camille (2018). Provocations: Collected Essays. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 9781524746896.

- Porter, Roy (1996). "Is Foucault Useful For Understanding Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Sexuality?". In Keddie, Nikki R. (ed.). Debating Gender, Debating Sexuality. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-8147-4655-1.

- Posner, Richard (1992). Sex and Reason. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-80279-7.

- Ricœur, Paul (1970). Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02189-9.

- Robinson, Paul (1990). The Freudian Left. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9716-2.

- Schwartz, Joel (1990). "Freud and the American Constitution". In Bloom, Allan (ed.). Confronting the Constitution: The Challenge to Locke, Montesquieu, Jefferson, and the Federalists from Utilitarianism, Historicism, Marxism, Freudianism, Pragmatism, Existentialism... Washington, D. C.: The AEI Press. ISBN 978-0-8447-3700-3.

- Scruton, Roger (1994). Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation. London: Phoenix Books. ISBN 978-1-85799-100-0.

- Seidler, Victor J. (1987). "Reason, desire, and male sexuality". In Caplan, Pat (ed.). The Cultural Construction of Sexuality. London: Tavistock Publications. ISBN 978-0-422-60880-0.

- Sontag, Susan (1990). Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-26708-3.

- Weeks, Jeffrey (1993). Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths and Modern Sexualities. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04503-2.

- Journals

- Alford, C. Fred (1987). "Eros and Civilization after thirty years". Theory & Society. 16 (6). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Alford, C. Fred (1993). "Reconciliation with Nature? The Frankfurt School, Postmodernism and Melanie Klein". Theory, Culture & Society. 10 (2): 207–227. doi:10.1177/026327693010002011. S2CID 145412826. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Bertman, M. A. (1998). "Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse (Book Review)". Choice. 36 (4). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Beard, Michael (1998). "Apocalypse and/or Metamorphosis (Book Review)". Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures. 9 (1). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Bird-Pollan, Stefan (2013). "Critiques of Judgment". Radical Philosophy Review. 16 (1): 99–107. doi:10.5840/radphilrev201316112. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Casteel, P. D. (2017). "Marcuse & Administration". Marcuse & Administration -- Research Starters Sociology (April 1, 2017). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Celarent, Barbara (2010). "Eros and Civilization". American Journal of Sociology. 115 (6): 1964–1972. doi:10.1086/654745. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Cerullo, Margaret (1979). "Marcuse and Feminism". New German Critique. 18 (18): 21–23. doi:10.2307/487846. JSTOR 487846.

- Cho, Daniel (2006). "Thanatos and Civilization: Lacan, Marcuse, and the Death Drive". Policy Futures in Education. 4 (1): 18–30. doi:10.2304/pfie.2006.4.1.18. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Chodorow, Nancy Julia (1985). "Beyond Drive Theory: Object Relations and the Limits of Radical Individualism". Theory & Society. 14 (3): 271–319. doi:10.1007/BF00161280. S2CID 140431722. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Duvenage, Pieter (2017). "Filosofie as aktualiteitsinterpretasie. Marinus Schoeman as denker". Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe. 57 (1): 7–21. doi:10.17159/2224-7912/2017/v57n1a2. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Edel, Abraham (1956). "Instead of Repression". The Nation. 183 (1). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Escoffier, Jeffrey (2015). "Marcuse, Herbert (1898-1979)". GLBTQ Social Sciences. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Evans, Sara M. (2009). "Sons, Daughters, and Patriarchy: Gender and the 1968 Generation". The American Historical Review. 114 (2): 331–347. doi:10.1086/ahr.114.2.331. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Farr, Arnold L.; Kellner, Douglas; Lamas, Andrew T.; Reitz, Charles (2013). "Herbert Marcuse's Critical Refusals". Radical Philosophy Review. 16 (1). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Fernandes, Franco; Augusto, Sérgio (2016). "Sobre o uso do conceito de sublimação e suas derivações, a partir da perspectiva estética marcuseana". DoisPontos. 13 (3). doi:10.5380/dp.v13i3.47239. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Fingarette, Herbert (1957). "Eros and Utopia". The Review of Metaphysics. 10 (4).

- Grotjahn, Martin (1956). "Eros and Civilization. A Philosophical Inquiry Into Freud: By Herbert Marcuse. Boston: The Beacon Press, 1955. 277 pp". The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. 25: 429–431.

- Hammer, Espen (2008). "Marcuse's critical theory of modernity". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 34 (9): 1071–1093. doi:10.1177/0191453708098538. S2CID 143566595. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Hite, Molly (2010). ""Fun Actually Was Becoming Quite Subversive": Herbert Marcuse, the Yippies, and the Value System of Gravity's Rainbow". Contemporary Literature. 51 (4): 677–702. doi:10.1353/cli.2011.0004. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Holland, Nancy J. (2011). "Looking Backwards: A Feminist Revisits Herbert Marcuse's Eros and Civilization". Hypatia. 26 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01127.x. S2CID 143753926. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Howell, R. J. (1990). "Melanie Klein and critical social theory (Book Review)". Choice. 27. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Jay, Martin (1982). "Anamnestic totalization: Reflections on Marcuse's theory of remembrance". Theory & Society. 11 (1). doi:10.1007/bf00173107. S2CID 146846698. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Jones, Richard M. (1958). "The Return of the Un-Repressed". American Imago. 15 (2): 175–180.

- Kimball, Roger (1997). "The marriage of Marx & Freud". The New Criterion. 16 (4). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Kluckhohn, Clyde (1955). "A Critique on Freud". The New York Times Book Review: 30.

- Marcuse, Herbert (2013). "From Marx to Freud to Marx". Radical Philosophy Review. 16 (1): 25–30. doi:10.5840/radphilrev20131615. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Mattick, Paul (1956). "Marx and Freud". Western Socialist. March/April 1956.

- Moldenhauer, Jearld (1972). "Marcuse and the Gay Revolution". The Body Politic (6). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Moore, Duston (2007). "Whitehead and Marcuse". Journal of Classical Sociology. 17 (1): 83–108. doi:10.1177/1468795X07073953. S2CID 143850620. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Nicholas, Jeffrey L. (2017). "Refusing Polemics: Retrieving Marcuse for Maclntyrean Praxis". Radical Philosophy Review. 20 (2): 185–213. doi:10.5840/radphilrev201742576. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Nicholsen, Shierry Weber (2006). "The Accumulated Guilt of Humankind: On the Aesthetic in a Damaged World". Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie (22/23). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Nyberg, Paul (1956). "A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud". Harvard Educational Review. 26 (1).

- Privitello, Lucio Angelo (2013). "Teaching Marcuse". Radical Philosophy Review. 16 (1): 109–122. doi:10.5840/radphilrev201316113.

- Rayman, Joshua (2005). "Marcuse's Metaphysics: The Turn from Heidegger to Freud". Telos (131). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Shearmur, Jeremy (1983). "Social Amnesia (Book Review)". Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 13 (1). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Sica, Alan (2011). "The Case of Barbara Celarent, Champion Book Reviewer". Contemporary Sociology. 40 (4): 385–387. doi:10.1177/0094306111412511.

- Stakemeier, Kerstin (2006). "Eros im Fordismus Zur Ästhetisierung der Politik in den Fünfziger Jahren des 20. Jahrhunderts". Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie (22/23). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Stirk, Peter M. R. (1999). "Eros and civilization revisited". History of the Human Sciences. 12 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1177/09526959922120162. S2CID 144184630. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Tuttle, H. N. (1988). "Hegel's ontology and the theory of historicity (Book Review)". Choice. 25. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Walsh, Sean Noah (2008). "The subversion of Eros: Dialectic, revolt, and murder in the polity of the soul". Crime, Media, Culture. 4 (2): 221–236. doi:10.1177/1741659008092329. S2CID 145245919. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Weineck, Silke-Maria (2000). "Sex and history, or Is there an erotic utopia in Dantons Tod?". The German Quarterly. 73 (4): 351–365. doi:10.2307/3072756. JSTOR 3072756. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Whitfield, Stephen J. (2014). "Refusing Marcuse". Dissent. 61 (4): 102–107. doi:10.1353/dss.2014.0075. S2CID 143795306. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Wolff, Kurt H. (1956). "Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud". American Journal of Sociology. 62 (3): 342–343. doi:10.1086/222021.

- Young, Robert M. (1969). "The Naked Marx". New Statesman. 78 (November 7, 1969).

- "Marcuse's Conception of Eros". Radical Philosophy Review. 16 (1). 2013. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

External links

[edit]- Table of contents, with links to full texts of preface, 1966 preface, introduction, chapter 1, epilog, and index (at marcuse.org)

- Citations of numerous reviews in 6 languages, with links to on-line texts

- Review by Paul Mattick

- Review by Robert M. Young