Ernst Heilmann

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (May 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Ernst Heilmann | |

|---|---|

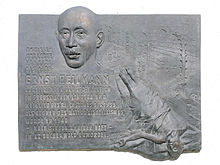

Memorial for Heilmann in Kreuzberg | |

| Member of the Reichstag | |

| In office 1928–1933 | |

| Constituency | Frankfurt (Oder) |

| Leader of the SPD in the Landtag of Prussia | |

| In office 1921–1933 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 April 1881 Berlin, German Empire |

| Died | 3 April 1940 (aged 58) Buchenwald concentration camp, Nazi Germany |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Magdalena Heilmann |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Humboldt University of Berlin |

| Profession | Jurist |

Ernst Heilmann (13 April 1881 – 3 April 1940) was a German jurist and politician of the Social Democratic Party during the Weimar Republic.

Heilmann rose to prominence as a proponent of the German party truce (Burgfriedenspolitik) during the First World War. From 1921 he was leader of the SPD's parliamentary group in Prussia, Germany's largest state, where he played a key role in stabilising the moderate democratic Weimar Coalition that governed the state until July 1932. He was elected to the Reichstag in 1928 and was prominent in the party press during the rise of the Nazis. As a high-profile Jewish Social Democrat, he was subject to frequent rhetorical attacks particularly by the Nazis, including a death threat by Wilhelm Frick in 1929. Not long after the Nazi seizure of power, Heilmann was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned in a series of concentration camps in which he was to spend nearly seven years. He was murdered at Buchenwald in April 1940.

Education and early career

[edit]Heilmann was born in Berlin into a lower middle-class, secular Jewish family. He attended Köllnisches Gymnasium and then Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he studied law and political science. He was barred from completing his legal traineeship due to his involvement in the Social Democratic Party, which he joined at age 17.

In 1909, Heilmann moved to Chemnitz to work on the editorial staff of the local Social Democratic newspaper. He served a six-month prison sentence in 1911 for reporting on a local strike. During his time in the city he spoke frequently about a broad number of topics in connection with his political work, including elections, foreign affairs, economics, and history. He also wrote a history of the labour movement in the region.

Heilmann called for peace during the July crisis, but after the outbreak of war in August became a strong advocate of Burgfriedenspolitik, supporting the German war effort. He distinguished himself particularly as one of few Social Democrats to call for a thorough German victory, including annexations of territory. He volunteered for military service in 1915 and was discharged the following year after suffering injuries which left him blind in one eye. Thereafter he moved to Charlottenburg in Berlin, where he wrote for various moderate Social Democratic publications.

In Prussia

[edit]During the November Revolution, Heilmann advocated against further revolutionary developments and for parliamentary democracy, in line with the rest of the party right-wing. In early 1919 he was elected to the Charlottenburg district council as well as the Landtag of Prussia.

In 1921 Heilmann became parliamentary leader of the SPD's Landtag faction.[1] He was an able leader of the largely moderate, reform-oriented parliamentary group and a close supporter of the party's likeminded Minister-President Otto Braun. He also enjoyed an effective collaboration with the Catholic Centre and its parliamentary leader, Joseph Hess; together they ensured the stability of the government and navigated numerous conflicts. Heilmann was an adept politician in his own right; in 1926 he was able to install Albert Grzesinski as interior minister against opposition from both Otto Braun and the SPD faction, and in 1930 succeeded in a campaign to secure the departure of culture minister Carl Heinrich Becker.

Heilmann was proud of the reform and democratisation of state administration which he believed had transformed the Prussian police into a reliable ally of the republic. He viewed Prussia as a stabilising force in Germany, particularly during the "crisis year" of 1923. The state government oversaw public investment in housing, education, electricity, and agricultural cooperatives.

Defence of the republic

[edit]Heilmann was appointed editor of the SPD weekly Das freie Wort in October 1929 and commentated regularly until the Nazi seizure of power. He was a strong supporter of the Weimar Republic and parliamentary democracy, disparaging the disdain for the republic evident among some wings of the SPD. He believed it was the duty of the SPD to govern in coalition in order to improve and strengthen the republic in a Social Democratic direction: "If the bourgeois bloc ruled permanently in the Republic, how would you rouse the enthusiasm of the workers?" Shortly after the collapse of the second Müller cabinet in March 1930, Heilmann led the Landtag faction in condemning the SPD Reichstag faction's withdrawal from government.

Heilmann was keenly aware that the republic's position remained precarious despite success in Prussia. In 1928 he sharply attacked the republic's enemies both on left and right; despite his reformist tendencies, he emphasised: "We must never make the mistake of thinking that we can overcome this backwardness [reaction and authoritarianism] with parliament alone." He polemicised regularly against the Communist Party of Germany and in 1930 condemned celebrations organised by the SPD's youth wing to commemorate Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

He was particularly hostile to the Nazi Party, highlighting its violence and describing the movement as "a relapse into brutality and barbarity". In 1929 Heilmann was the subject of a death threat from Wilhelm Frick, who in a speech in the Reichstag proclaimed that Heilmann would be "the first to be hanged" by a Nazi court in "the coming Third Reich". Frick was not reprimanded for his threat, nor was it reported by the press, including the Social Democratic press.[1]

Heilmann was a strong advocate of the SPD's toleration of the cabinet of Heinrich Brüning, considering it vital to the maintenance of the Prussian coalition. The Prussian Centre party had made it clear that if the SPD toppled the Reich government, the Centre would bring down Braun in turn. Prior to the 1932 Prussian state election, Heilmann helped engineer an amendment to procedure to ensure that the government could only be toppled by an affirmative majority for a new Minister-President, not simply removed by a hostile majority (constructive vote of no confidence). This meant that, despite the Weimar coalition's defeat in the election, the Nazis' inability to form a coalition allowed Braun to remain in office.

The defensive strategy advocated by Heilmann and like-minded Social Democrats prevented Hitler from taking power throughout 1932, though it could not save the Prussian government, which was deposed by Reich decree on in July. Nonetheless, toward the end of the year, Heilmann believed his strategy had proven successful. After the November 1932 German federal election in which the Nazis lost ground for the first time, Heilmann wrote: "Today, no normal person can believe in the Hitler dictatorship anymore."

Nazi period

[edit]

Heilmann refused to flee the country after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor, despite his high profile as a Nazi opponent. He rebuffed offers of safe passage, stating he could not leave since "our members, the workers, cannot run away either." The speech given by Otto Wels in opposition to the Enabling Act of 1933 was co-authored by Heilmann, Wels, Kurt Schumacher, and Friedrich Stämpfer. He remained active in the SPD through June, advocating a strategy of legality to delay suppression of the party as long as possible.

On 26 June, four days after the SPD was banned, Heilmann was arrested by the Gestapo at Café Josty and sent to Columbia concentration camp before being transferred to the police prison on Alexanderplatz. He was severely mistreated in these first few days. Over the following years he remained imprisoned and was sent to numerous different camps, finally ending up in Buchenwald concentration camp in September 1938. He suffered greatly and attempted suicide at least once. Speaking to fellow inmate Walter Poller, Heilmann remarked of the future: "There will be war; you will have a chance, for they will need you. But we Jews will all no doubt be struck dead."[1]

On 31 March 1940, Heilmann was called out at the evening roll call and led to the bunker of the Buchenwald concentration camp. On the morning of 3 April, he was murdered by SS-Hauptscharführer Martin Sommer via lethal injection. The report to the camp commandant stated that Heilmann had died at 5:10 AM "from heart failure due to heart defect (dropsy)". The official SS protocol, however, claimed that extreme old age was the cause of death.

Heilmann was survived by his wife Magdalena, to whom he had been married since 1920, and four children.

Legacy

[edit]Despite his contemporary prominence, Heilmann was an obscure figure in Weimar historiography until the 1970s. He was mentioned only briefly or not at all in memoirs by Otto Braun, Carl Severing, Albert Grzesinski, Friedrich Stämpfer, Heinrich Brüning, and Arnold Brecht. He was recognised by Hedwig Wachenheim, who described him as a model parliamentary leader and one of the greatest political figures of the Weimar Republic, crediting him with contributing to the long reign of Prussia's Weimar coalition.[1]

Heilmann was first highlighted in a major publication by Hagen Schulze in his 1977 biography of Otto Braun for his role in the success of the Prussian coalition. Peter Lösche and Horst Möller published works on Heilmann at the beginning of the 1980s and each described him as one of the most significant figures of the era. This was followed by a radio feature about Heilmann by Rainer Krawitz in 1981 and an essay by Stephan Pfalzer in 1993 discussing his activities in Chemnitz. Wolfgang Röll, an employee at the Buchenwald Memorial, dedicated several pages to Heilmann in his work discussing Social Democratic prisoners of the camp. A comprehensive biography of Heilmann is yet to be written and he is still largely unrecognised.[1]

Heilmann is memorialised in various locations, particularly in Berlin. A hall at the Berlin House of Representatives, site of the former Prussian Landtag, is named in his honour. A plaque was installed in 1989 at his former home at Brachvogelstrasse 5 in Kreuzberg. He is also featured in the Memorial to the Murdered Members of the Reichstag at the Reichstag building. Streets in Berlin, Chemnitz, Cottbus, Hildesheim, Forst (Lausitz), Bergkamen and Niederheimbach are named for Heilmann. His final resting place in Wilmersdorf Forest Cemetery Stahnsdorf has been designated as a grave of honour by the state of Berlin since 1999.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kay, Alex J. (February 2012). "Death Threat in the Reichstag, June 13, 1929: Nazi Parliamentary Practice and the Fate of Ernst Heilmann". German Studies Review. 35 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1353/gsr.2012.a465655. JSTOR 23269606. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Lösche, Peter; Scholing, Michael; Walter, Franz (1988). "Ernst Heilmann (1881–1940). Parliamentary Leader and Reform Socialist". Saved from Oblivion: Life Stories of Weimar Social Democrats (in German). Colloquium Verlag. p. 99-120.

- Möller, Horst (2003). "Ernst Heilmann. A Social Democrat in the Weimar Republic". In Wirsching, Andreas (ed.). Enlightenment and democracy. Historical studies on political reason (in German). Oldenbourg. pp. 200–225. ISBN 3-486-56707-1.

- Winkler, Heinrich August (May–June 1990). "Choosing the Lesser Evil: The German Social Democrats and the Fall of the Weimar Republic". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (2/3): 205–227. doi:10.1177/002200949002500203. JSTOR 260730.

External links

[edit]- Klaus Malettke (1969), "Heilmann, Ernst", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 8, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 260–261

- Ernst Heilmann in the German National Library catalogue

- 1881 births

- 1940 deaths

- Politicians from Berlin

- Jurists from Berlin

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

- Prussian politicians

- Social Democratic Party of Germany politicians

- German people who died in Buchenwald concentration camp

- Politicians who died in Nazi concentration camps

- German civilians killed in World War II

- Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic