Emma B. Freeman

Emma B. Freeman | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, c. 1913 | |

| Born | Emma Belle Richart January 1880 Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | March 1928 San Francisco, California |

| Movement | Pictorialism |

Emma Belle Freeman (1880–1928) was an American photographer based in northern California. Her portraits of Native American subjects from the 1910s were widely published and exhibited at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in 1915. She created landscape photography and was a commercial photographer, creating soft-focused and artistic pictorialist images that she often retouched and hand-colored. Her photographs of the rescue of the crew of the grounded USS Milwaukee in Humboldt Bay led to her being appointed an official United States Navy photographer. Her 1915 divorce was the subject of a scandal when it was alleged that there had been misconduct during a train trip she took from Eureka to San Francisco with Illinois Governor Richard Yates Jr.

Early life and marriage

[edit]Emma Belle Richart was born on a farm in Nebraska in January 1880 to Belle (née Zoover) and William K. Richart, homesteaders from Ohio.[1] She wanted to be an artist from an early age.[2]

By 1902, she was living in Denver, working at a department store at the ribbon counter and selling her paintings.[2] That year she married garment industry salesman Edwin Ruthven Freeman and they moved to San Francisco. She and her husband had a stationery and art goods store. She took classes in painting and drawing from Giuseppe Cadenasso.[1] Their store was burned in a fire during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. They then moved to Eureka where they started the Freeman Art Company and began creating scenic photography.[3]

Photography career

[edit]

Freeman was a self-taught photographer who started learning the trade around 1910.[3][2]

In 1913, after Illinois Governor Richard Yates Jr. had a speaking engagement at a Chautauqua in Eureka, Freeman took a train with him to San Francisco, stopping for the night at a hotel in Willits. The trip caused a local scandal,[3] with allegations that Yates had kissed Freeman and was partially undressed in her hotel room. Freeman divorced her husband in 1915 and during a widely publicized jury trial in July 1915, Yates was cleared of charges of misconduct.[4] After the divorce, Freeman dedicated more of her time to photography. She became the sole proprietor of Freeman Art Company, specializing in landscapes and artistic portraits.[1]

Freeman took a series of portraits of local Hupa and Yurok people from 1914 to 1918. Her photographs were staged[5] in studio and outdoor settings in Humboldt County and Eureka. As a pictorialist, she created stylized portraits using a soft focus. She often retouched and hand-colored her prints, sometimes adding allegorical details. Her compositions involved contrived poses and settings that often inaccurately depicted Indigenous culture and clothing. She also photographed elderly residents at the Klamath and Hupa reservations.[6]

Freeman's Northern California series, features 200 photographs depicting Native Americans from the Klamath River area. She sold prints from the series and gained recognition for her work at the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.[3][2] Photographs from the series were widely published in publications such as Camera Craft, Overland Monthly, Collier's, The Argonaut, and Sunset.[2] It has been suggested that "N. A. Wog", the author of a May 1917 article entitled "An Artist with a Camera", praising Freeman's work in Camera Craft magazine was actually Freeman herself.[1]

In 1917, she photographed the rescue of the crew of the USS Milwaukee in Humboldt Bay, where it ran aground while trying to salvage the grounded submarine USS H-3.[3] She was the first photographer to arrive at the scene and took over 200 photographs of the wreck. Her photographs were published in The Tribune and led to her being named an official United States Navy photographer and being invited on board the Milwaukee to take more photographs.[7]

Freeman's photographs showed the impact of roadside logging on the redwoods of Humboldt County accompanied national magazine stories by Madison Grant of the Save the Redwoods League.[8] Collections of Freeman's photographs were published as books, including Northern California Series.[5]

Freeman returned to San Francisco in 1919, selling gifts and souvenirs out of a three-story building downtown that served as an art store and photography gallery. The third floor held her studio with prints of her photography, the second artwork of Northern California including Native American baskets, and the first art supplies. She also did work in advertising for the department store I. Magnin and Company, one of her first commercial clients.[9] She went bankrupt in 1923 due to competition and a dishonest business partner. She moved to a smaller store[9] before retiring and marrying bookkeeper Edward Blake in 1925.[3]

Freeman had a stroke on December 24, 1927. She died in San Francisco, California, in March 1928.[9] Her works are held by the Newberry Library and the California State Library. Peter E. Palmquist wrote the 1976 monograph With Nature's Children: Emma B. Freeman (1880-1928); Camera and Brush about her life and photography.[1]

Gallery

[edit]-

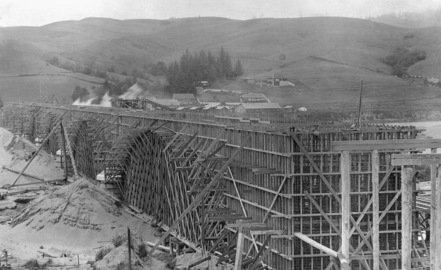

Construction of Fernbridge in 1911

-

Maypole dance

-

Marines in front of the Rialto

-

The Automobile Trip with Bertha Stevens and Emma B. Freeman

-

Canoer

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Palmquist, Peter E. (1976). With Nature's Children: Emma B. Freeman (1880-1928); Camera and Brush. Eureka, California: Interface California Corp. pp. 12, 18–20. ISBN 0-915580-10-1.

- ^ a b c d e Genzoli, Andrew (December 8, 1975). "Redwood Country: Emma B. Freeman information". Eureka Times Standard. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Commire, Anne, ed. (2002). "Freeman, Emma B. (1880–1927)". Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Connecticut: Yorkin Publications. ISBN 0-7876-4074-3.

- ^ "Yates Didn't Kiss". The Sedalia Democrat. July 30, 1915. p. 1.

- ^ a b Durston, Tammy (2017). Northern California's Lost Coast. Arcadia Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4671-2544-4.

- ^ "Emma B. Freeman photographs of Yurok and Hupa Indians [1914-1918]". Edward E. Ayer Photograph Collection (Newberry Library).

- ^ "Woman Named Official Navy Photographer". Oakland Tribune. January 31, 1917. p. 16.

- ^ Wasserman, Laura; Wasserman, James (2019). Who Saved the Redwoods: The Unsung Heroines of the 1920s Who Fought for Our Redwood Forests. Algora Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-62894-375-7.

- ^ a b c Ressler, Susan R. (2003). Women Artists of the American West. McFarland. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7864-1054-5.