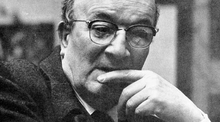

Emilio Cecchi

Emilio Cecchi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 July 1884 |

| Died | 5 September 1966 Rome, Lazio, Italy |

| Occupation(s) | Author Literary critic Arts critic Movie producer Movie director |

| Years active | 1932–1949 (film) |

| Spouse | Leonetta Pieraccini |

| Children | Mario, 1912 Giuditta, 1913 Giovanna "Suso",1914) Dario, 1918 |

Emilio Cecchi (14 July 1884 – 5 September 1966) was an Italian literary critic, art critic and screenwriter.[1][2][3] One English language source describes him as "an 'official' - although radically anti-academic - intellectual".[4]

He was made artistic director at Cines Studios, Italy's leading film company, in 1931, remaining in the post for slightly more than a year. He also directed two short documentaries in the late 1940s.[2][5]

Biography

[edit]Provenance and early years

[edit]Emilio Cecchi was born in Florence, second of the six recorded children of Cesare and Marianna Sani Cecchi. The family had their home in the city center among the narrow streets between the Porta San Gallo and the cathedral, but Cesare Cecchi came originally from the countryside: he worked in an Ironmonger's store.[3] Emilio's mother, like many Florentines, had her own little tailoring workshop.[6] The family was close-knit and loving, but Cecchi would nevertheless look back later on a childhood scarred by tragedy. Annunziata, his elder sister, was seriously ill over many years and died of tuberculosis in 1902. His father was devastated by the experience. Emilio Cecchi later wrote of how, when his father left his work, they would meet up and walk to the church where for long hours they would kneel together side by side working through their grief and - at least in the case of the boy - studying the detail of building's elaborate interior architecture.[3]

Cecchi attended the middle school run by the Piarists, receiving his school diploma in 1894. That opened the way for him to move on to technical school, and from there to the technical-commercial institute, from where in 1901 he emerged with a diploma in book-keeping and accountancy.[3] It was an unusual achievement for one from a relatively impoverished background and he was rewarded by being sent to take a holiday with an uncle of his father's who lived at San Quirico d'Orcia, a hill-town on the far side of the neighbouring Province of Siena. He had already embarked on a serious attempt to teach himself how to paint when he was just twelve, and he was now inspired by the Senese countryside to resume his artistic studies through both practical endeavour and reading.[3][7] Back in Florence he became a regular presence in the Gabinetto Vieusseux (library) where his energetic autodidacticism was again to the fore. He discovered the works of Gabriele D'Annunzio, a dominating presence in early twentieth century literature.[3] He also ingested parts of the multi-volume compendium "la Storia della pittura in Italia" ("The History of Painting in Italy"), by Cavalcaselle and Crowe.[8] He made sketches of a number of pictures that particularly interested him and took the opportunity to make the acquaintance of Giani Stuparich and Diego Garoglio, who were teachers of Giovanni Papini, and who provided him with advice on his further reading.[3] (Garoglio recommended Baudelaire and Poe.) These, along with Vittorio Scialoja whom he met at around the same time, exercised a significant influence on his early development as a scholar of the visual arts.[3] During 1901/02 he undertook a period of military service, which he was able to do while continuing to be based in Florence.[3][7] In 1902 he took a job with the Credito Italiano (bank).[6] From there he moved on, in 1904, to a job as a copyist in the offices of the city hospital.[6] Whenever he was not working, night and day, he was studying the visual arts.[6] As a critic he would later gain a particular reputation for his expertise on the Senese School and the Florentine "Quattrocento", both topics on which in due course he would publish insightful books of reference.[3] A milestone came when he received classics diploma from the prestigious "Convitto nazionale statale Francesco Cicognini" educational institution in Prato.[6]

Networking

[edit]Although Cecchi's progression from humble beginnings to nationally respected literary and arts scholar reflected his own remarkable talent, energy and determination, it was also a tribute to Florence, which during the early years of the twentieth century was among the most open and intellectually lively cities in Italy. He was appreciative of this, even though he continued to be dogged by family tragedy. In 1903 his brother Guido fell ill with the tuberculosis that had killed their sister, while Emilio himself was also suffering from bouts of serious illness.[7] Guido died in 1905. Still in 1903, Emilio Cecchi and the polymath writer-philosopher Giovanni Papini became friends. Another new friend that year was the painter and ceramicist Armando Spadini. Cecchi connected with a circle of students from the "Florence Institute of Higher Studies" ("Istituto di Studi Superiori") which also included Giuseppe Antonio Borgese, Giuseppe Prezzolini and Ardengo Soffici. With friends such as these, it is not entirely surprising that in 1903 Emilio Cecchi made what some regard as his own critical debut, with an article entitled "Il concerto", which appeared under the pseudonym "Aymerillot" in the review magazine Leonardo.[3][9]

Columnist

[edit]In 1906 Cecchi finally left Florence and relocated to Rome. He wrote for various Roman literary publications including, notably, Athena and Nuova Antologia.[10] At this stage his stay in Rome was relatively brief, however, since he decided to study for a further academic qualification. Having studied "as a privateer" for his classics diploma from the "Convitto nazionale statale Francesco Cicognini", he was able to enrol at the Literature Faculty of the "Istituto di Studi Superiori". His student career provided an opportunity for more networking. New friends included Scipio Slataper and the northerner Carlo Michelstaedter. Another contemporary was Giuseppe De Robertis.[11] Cecchi did not pursue his studies to the point of graduation (although an honorary degree which the institute conferred on him in 1958 may have implied a reassuring measure of retrospective recognition).[4] Meanwhile, he continued to engage as a literary critic, at times focusing as much on Russian, German or English literature as on Italian.[3]

Marriage and family

[edit]In 1911 Emilio Cecchi married Leonetta Pieraccini (1882 - 1977),[12] an artist and the daughter of a physician from Poggibonsi a little town set in the wine country approximately midway between Florence and Siena. However, the couple now made their home not in Tuscany but back in Rome. The marriage would be followed by the births of their four children in 1912, 1913, 1914[13] and 1918.[4] (Their eldest child, a son, died in infancy, however.)

The critic-translator, Masolino D'Amico (born 1939), is Emilio Cecchi's grandson.[14]

In Rome

[edit]Back in Rome he contributed assiduously to La Tribuna, a daily newspaper published between 1883 and 1946. He also time to work for rival publications, of which probably the most significant, at least initially, was the weekly literary magazine La Voce. However, he increasingly found himself in opposition to editorial decisions by the La Voce under its editor in chief, his fellow Florentine Giuseppe De Robertis. Cecchi's article "False audacie" appeared in "Tribuna" on 13 February 1915. It robustly criticised Papini's "Cento pagine di poesia" ("A hundred pages of poetry") and triggered a similarly robust reaction from Papini in La Voce on 28 February 1915. Further back and forth exchanges between the two, published respectively in "Tribuna" and "Voce", followed, and other literary commentators joined the fray. However, as 1915 progressed, larger political developments intervened.[3]

Although using "Tribuna" for his feuding with antagonists in the literary journals was no doubt an effective way to raise his profile among Rome's intellectuals, it was not necessarily Cecchi's most important work during this period. His circle also included erudite scholars such as Roberto Longhi and Grazia Deledda. His 1912 essay on the work of Giovanni Pascoli is regarded as one of his best, containing insights as valid today as when it first appeared.[3] Over the next two or three years he concentrated principally on English and Irish literature, producing several significant translations. Swinburne and Meredith were particular favourites. Nevertheless, he certainly did not avoid Italian poetry. He was an enthusiastic admirer of Dino Campana, "the best poet we have".[15]

He also contributed to the Fascist daily Il Tevere.[16]

War years

[edit]In 1914 the Italian government had resisted participation in the First World War. Major belligerent powers on both sides were keen to reverse that decision. Italy's territorial aspirations were no secret, and in April 1915, sufficient inducements having been secured from the British, the Italian government agreed (at that stage secretly ) to join in with the fighting on the British side: Italy formally declared war on Austria the next month, by which time, despite a widespread conviction that the country was not well prepared for such a venture, large scale military mobilisation was already underway. On 10 May 1915 Cecchi was mobilised and sent to join thousands of others in the newly enlarged army. He gave careful thought to the question of which newspapers or journals should benefit from his written reports, but evidently decided to stay faithful:[17] on 28 June 1915 it was "Tribuna" that printed the first in a succession of reports by Emilio Cecci from the Austrian front. Meanwhile, his "History of nineteenth century English literature" ("Storia della letteratura inglese nel secolo XIX") on which in one way and another he had been working since at least as far back as 1903, was published in Milan.[3][4] The study of English-language literature was a theme to which he would return regularly through the ensuing decades.[3]

Despite the formidable energy he devoted to networking, it was only on 15 December 1915, while in Rome on leave from the frontline, that Cecchi had his first meeting with the man whose poetry he had eulogised in print, Dino Campana.[10]

In September 1916 he was assigned to the commissariat of the 8th Army Corps. This involved a posting to his home city of Florence. His wife and small children also relocated back to Florence from Rome. In Florence his military duties seem to have left him with sufficient time and opportunity to embrace family life and attend to his reading. He even passed some exams at the university during this period.[10] In September 1917, however, he was promoted to the rank of captain, and posted to the defensive "Line of the Seven Communes" on the northern front. Cecchi's letters of the time indicate that his 1917 transfer to the frontline was unexpected and unwelcome.[10]

During 1918 Cecchi was a contributor to Piero Jahier's so-called trench newspaper, "L'Astico" (which took its name from a mountain river in the fighting zone).[7] Many of Cecchi's wartime letters, providing an excellent source for researchers. Along with Jahier, those with whom he was in contact through these years included Michele Cascella, Riccardo Bacchelli, Benedetto Croce (who valued his contributions to his magazine "La Critica") and Gaetano Salvemini.[10]

Aftermath of war

[edit]On 13 November 1918 Cecchi arrived in London, sent by Olindo Malagodi to work as a correspondent for "Tribuna". His mandate included some news reporting.[3] Till now, Cecchi's relationship with journalism had been uneven. He had been inclined to treat newspaper work as a distraction from serious scholarship, but it was a distraction that was frequently necessary to put food on the table.[18] The opportunities presented by the chance to travel to London generated a more enthusiastic reaction, however.[18] He made good use of the opportunities. In England he visited Chesterton at his home in Beaconsfield.[18] He later helped promote Chesterton's work to Italian readers: his contribution included translating some of the texts into Italian.[3][10] Another of England's literary celebrities whom he met during his stay in England, whose writing he would translate and champion after his return to Italy in 1919, was Hilaire Belloc.[18][19] During his months in England Cecchi agreed an arrangement with the Manchester Guardian and Observer, two nationally distributed English newspapers of the political centre-left. He became a regular correspondent for The Guardian from Italy between 1919 and June 1925.[20] His contributions, most of which were submitted in Italian and then translated by newspaper staff in England, generally appeared without attribution.[3]

La Ronda

[edit]During 1919 the Cecchi's moved back from Florence to Rome, where Cecchi was one of the (apparently self-identified) "seven wise men" who co-founded and then co-produced La Ronda, a literary magazine published in Rome four times a year between 1919 and 1923.[21] The other six were Riccardo Bacchelli, Antonio Baldini, Bruno Barilli, Vincenzo Cardarelli, Lorenzo Montano and A. E. Saffi. The slaughter of war had triggered a widespread retreat from the wilder optimism of the modernists. The "wise" (and in several cases strikingly young) men who created La Ronda were engaged in a mission to return to older literary traditions, following the excesses of the Avant-garde.[3] Indeed, during the first half of 1919 Cecchi contributed a thoughtful piece entitled "Ritorno all'ordine" (loosely if inadequately translated, "Return to order").[3] Of the "seven wise men", it was Vincenzo Cardarelli who most unambiguously sought to set the tone for La Ronda. Cardarelli was a cautious man whose instincts led him to defend traditional principals and conservative values. Cecchi was also by temperament a cautious and conservative man, but he was also driven by intellectual rigour which was reflected in a determination to apply a scholarly and evidence-driven approach in his articles. The post-war period was a time of change and uncertainty. Cecchi felt that intellectuals - especially intellectuals with access to the power of the published word - a strong duty to acknowledge and participate in the developments in public life, and not simply to deny the nuances in the shifting realities of the age. The result was that during La Ronda's four year life the differences in perspective between the principal contributors to it were increasingly apparent to readers.[3]

More important than the philosophical tensions and contradictions between the contributors to La Ronda was the fact that some of Italy's best young literary commentators had the freedom to follow their own intellectual paths, which especially in the case of Cecchi meant satisfying the constant desire for enquiry and research. This quickly came to be expressed in a remarkable degree of mutual respect and tolerance between the seven "Ronda" founders, irrespective of sometimes strong differences in underlying assumptions. Cecchi contributed a number of essays and reviews on English and American authors in which he demonstrated a new level of structure and clarity. The subjects chosen and the Elzeviro layout[18] in which they appeared conferred additional authority on his written contributions. He continued to expand his own horizons by discovering new authors such as Carlo Cattaneo along with new works by authors whom he already knew well, such as Chesterton.[3] (His first translation into Italian of Manalive / "Le avventure di un uomo vivo" dates from this period.)

Despite earlier difficulties with its former editor, Cecchi still made contributions to La Voce. At Voce, however, he was well down the informal hierarchical structure, regarded as a young and raw talent at Voce, where internal politics were often conflictual. At Ronda Cecchi was able to contribute almost entirely on his own terms: in the process he acquired and demonstrated a well-rounded and well defined voice that was very obviously his own.[3]

Pesci rossi

[edit]The years 1919 and 1920 were intensely busy one for Cecchi. 1920 saw the publication of his book "Pesci rossi" (loosely, "Gold fishes") which some see as the most important and characteristic of his books. It was the only volume he published to which he did not return for a partial re-arrangement or rewrite in later years. "Pesci rossi" consists of seventeen beautifully crafted prose pieces (actually eighteen, since one in a merger of two originally separate essays) produced by Cecchi between 1916 and 1919. All except one had previously appeared in "Tribuna" or "Ronda".[3]

The topics are diverse: public and private events, sometimes seemingly inconsequential, things read, people met, personal memories, observations of nature concerning plants or animals. There is a sense in which the book represents the launch by Cecchi of an entire new genre that will stand out as representative of Italy's literary panorama between the twentieth century world wars.[3] The approach works best where the critic Cecchi controls the author Cecchi, and the quality of the prose is a function of the constructive tension between the two. The outcome is a sort of supervised lyricism, and an element of insouciance hinting at detachment. There is nevertheless a balancing wit, cloaked in shrewd insight and frequent flashes of incisive humour. The simple power and beauty of Emilio Cecchi's writing style are themes to which sources return again and again.[3][6][14]

1920s

[edit]The interwar period coincided with the peak of Cecchi's career as a literary critic and authority. His writing style triggered discussion among contemporaries, with which he himself was willing to engage. There was a widespread belief at the time that writing for newspapers would be damaging to the prose style of practitioners. Cecchi fought, with his pen, to defeat this prejudice, using nothing more deadly than the careful precision and euphony of his own writerly artistry.[3]

In 1920 he began contributing to Valori plastici, a recently launched fortnightly magazine with a focus on the arts and the fashionable "Return to order" agenda. Cecchi was now pursuing two parallel but closely intertwined careers as both a literary critic and an arts critic.[22] Between 15 July 1921 and 30 November 1923 he was contributing a weekly column to "Tribuna", in a section entitled "Libri nuovi e usati" ("Books new and second-hand": The title was later recycled and used for a volume of Cecchi essays published in 1958.) Authorship of the Tribuna column was attributed by means of the pseudonym "Il Tarlo" ("The bookworm").[10] The regular column gained for Cecchi growing and widespread respect, as he transitioned from the status of "another critic" to that of a cultural and literary authority.[3] Between December 1923 and the end of 1927 he was writing regularly for La Stampa, a nationally distributed and respected daily newspaper published in Turin.[4][23] In 1924 he also became a staff member at Il Secolo, a daily national newspaper based in Milan, to which he contributed as literary critic, filling the shoes of the highly respected Enrico Thovez as the latter fell terminally ill.[3]

In 1922 Cecchi, like other journalists, found himself reporting la "conquista del potere da parte di Mussolini" (the "conquest of power on the part of Mussolini). For writers of Cecchi's generation, attitudes to the Mussolini government would be endlessly discussed by subsequent generations of scholars. Characteristically, Cecchi's reactions to "the leader" were undogmatic, nuanced and at times, frustratingly for some, apparently fluid. Both from his published contributions to literary criticism and from the many notebooks in which he collected his thoughts, it is possible to detected an attitude of "dignified liberal detachment" during the early years of Fascism. It was an attitude widely shared among European intellectuals of the time.[3] In 1925, as Mussolini's polarising tendencies had their effect, Cecchi was among those who added his signature to Benedetto Croce's Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, a somewhat reactive - and in the context of subsequent events cautious - document which nevertheless represented a reproach to the populist enthusiasm that had carried the Fascists to power.[24] It is worth bearing in mind that the "manifesto" to which Cecchi added his signature was produced less than a year after the murder of Giacomo Matteotti by fascist thugs had served notice that the relaxed attitude to the more unsavoury aspects of Fascism that had hitherto been mainstream among Italian intellectuals was perhaps not the easy option it might once have seemed.[25] By 1935, however, the passage of time and events in Germany had to some extent "normalised" Fascist government. That year Cecchi, entrapped according to one sympathetic source by the seductive lure of political power, agreed to accept the Mussolini prize for literature, which he was awarded the next year.[3][26] In the eyes of post-1945 critics Cecchi's political credibility was further compromised in July 1940, less than a month before, following much anguished speculation, the government implemented a controversial decision to engage militarily in the Second World War, when he joined the Royal Academy, widely seen by this time as a tool of government.[3]

In 1927 he joined the "Corriere della Sera", a Genoa-based mainstream national newspaper to which he would contribute regularly (though not entirely without interruption) for the next forty years.[4][6] He also teamed up in 1927 with his old friend Roberto Longhi, becoming co-editor of "Vita Artistica".[27]

Several sources mention the delight that Cecchi took in international travel, notably to Great Britain and the Netherlands. He travelled further in 1930 when he accepted an invitation to spend a year in California as "Chair of Italian Culture"[28] and teach at Berkeley.[3][29] He was able to explore the cultural life San Francisco in some depth and also, before returning to Europe, satisfy a "longstanding desire" to get to know Mexico.[3][29] Naturally he shared his experiences and impressions with readers of the Corriere della Sera and - mostly posthumously - with scholars accessing his copious legacy of well-filled notebooks.[29]

1930s

[edit]During the 1930s Emilio Cecchi produced several volumes that libraries and book shops tend to classify as "travel literature".[30] Other biographers insist that these are better understood as books of essays, following the pattern set by "Pesci rossi" (1920), which just happen to be concerned with his travels. Perhaps the most successful of these is "Messico" ("Mexico"), a compilation of some of the best essays submitted to Corriere della Sera during his time in north and Central America. In it he shares his fascination with the remote and shadowy civilisation that once existed in Mexico. Less satisfactory is his book "Et in Arcadia" (1936), based on a lengthy visit through Greece in 1934: the book echoes the well-trodden tourist trail which many of his wealthier readers might already have worked through for themselves. A third "travel book", entitled "America amara" (1939) reproduced more of the articles he had provided to Corriere della Sera during his American year in 1930/31, and complemented these with further essays based on a subsequent visit to the American west coast undertaken by Cecchi during 1937/38.[3]

For Cecchi the 1930s were a decade of intense professional activity, extending far beyond the publication of his "travel literature". He contributed extensively to regional arts and cultural magazines in the Ugo Ojetti stable, such as Dedalo (Milan), Pegaso (Florence) and Pan (Milan), with a particular focus on the modern American classics.[31] "Scrittori inglesi e americani" ("English and American writers"), published in 1935 brought together a number of essays relating to the same themes. In the first edition English authors predominated, but in subsequent versions there were more American writers, reflecting Cecchi's discoveries in American literature during and following his year in California.[3]

In 1942 Cecchi used his literary celebrity to endorse the publication of "Americana", a compilation from contemporary American "narratori" (loosely, "story tellers") that had been put together by Elio Vittorini, an outspoken Milanese critic of Mussolini. The book had been blocked by Fascist censors in 1941. Cecchi adapted the book to the political and military situation of the times by substituting for Vittorini's original an introduction denouncing the "letteratura impegnata" (loosely, "politicised literature") and "democracy" of the United States.[32] After an abrupt change in Italian politics in 1943 Cecchi would insist that the commitment implicit in his more political actions under the polarising Fascist régime had reflected his strong Italian patriotism rather than any sort of political endorsement of the Fascist government. Later biographers, while admiring of his scholarly abilities and energies, and in personal terms sympathetic, have nevertheless felt it necessary to adopt an apologetic tone in respect of what many would construe as Cecchi's political misjudgements during the closing chapters of the Mussolini era.[3]

During the 1930s and early 1940 Cecchi also worked closely with Giovanni Gentile on the "Enciclopedia Italiana" contributing, in particular, numerous entries on the arts and literature to Appendix II (1939-1948) of it.[3]

1940s

[edit]Admission in May 1940 to the Royal Academy no doubt reflected the skill and energy Cecchi was devoting his work in promoting and sustaining Italy's cultural and artistic heritage, though the fact that he was at the time working closely on the encyclopaedia project with Gentile, a philosophical mentor of Italian Fascism, may also have played its part.[33]

During the Second World War Cecchi continued to live in Rome with his family. Travel was not easy, but in 1942 he nevertheless managed a trip to Switzerland in order to attend the wedding of his daughter "Suso" to the musicologist (and painter) Fedele D'Amico.[3][34]

Cinema

[edit]In 1932 Ludovico Toeplitz of Cines appointed Emilio Cecchi to the position of artistic director at the company's new Rome studios. Cecchi had only recently returned from a year in California, where he had seized the opportunity to study at close hand the latest developments in Hollywood. He had been using his newspaper columns in Italy to write about the cinema, recognising the potential of the new art-form, and commending in particular the work of the young Italian movie directors Alessandro Blasetti and Mario Camerini. The appointment of a literary figure to such a position at Cines was nevertheless an unusual move, signalling the possibility of new directions for the movie maker. Cecchi surrounded himself with "writers and artists" and moved decisively towards a greater emphasis on "arts films", but without neglecting the popular end of the market. Among commentators a general improvement in the quality of the studio's output was noted. A number of pioneering documentaries were also made on Cecchi's watch.[35] However, Ludovico Toeplitz who had appointed him was finding himself under increasing pressure from the government, who were keen to take more of a "hands-on" role with respect to Italy's leading film studio. Toeplitz resigned his post in November 1933 (and emigrated shortly afterwards to England where he worked with Alexander Korda).[2][36] Cecchi left his job at Cines very soon after Toeplitz, but he sustained an interest in cinema through and beyond the 1930s, producing for the appropriate specialist magazines lucid and critical movie reviews and related articles, with a particular focus - as before - on American movies.[2][3]

Through the 1930s and 1940s Cecchi also produced a steady trickle of screenplays based on works of recent or contemporary Italian literature.[13] His screenwriting output peaked during the early 1940s, possibly reflecting a reduced demand for literary criticism in newspapers and magazines under wartime conditions. In 1940 and 1941 he worked on the script of Mario Soldati's Piccolo mondo antico and Mario Camerini's The Betrothed.[37]

More war years

[edit]During the war years Cecchi retained contact with friends and colleagues as far as possible. Visitors to the family home in Rome through this period included Alberto Moravia,[38] Elsa Morante, Leo Longanesi and Vitaliano Brancati.[39] After 1945 Cecchi quickly re-established the disrupted connections that he had sustained with newspapers during the pre-war period. Readers were again interested in high quality literary criticism.[3]

Post-war

[edit]Following a "brief flirtation" with the recently launched magazine Tempo, the publication to which Cecchi routinely contributed during his final two decades became the Corriere della Sera, published in Milan and distributed nationally.[3][9] In 1946 he took a trip to London.[9] Along with his domestic readership, he resumed his international contacts. Foreign publications for which he wrote regularly during the post-war period included La Parisienne, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Times Literary Supplement.

In 1947 Arrigo Benedetti recruited him to write for L'Europeo.[40] That same year he was appointed an academician of the Lincei.[6]

During the 1960s Cecchi teamed up with Natalino Sapegno to produce "Storia della letteratura italiana" ("History of Italian Literature"), a nine volume compendium published between 1965 and 1969. He authored many of the sections himself.[3]

Recognition

[edit]Emilio Cecchi was frequently singled out for commendation both on account of his vast knowledge and intensive scholarship and because of his meticulously crafted prose style.[3] In 1952 he was a recipient of the Feltrinelli Prize for non-fiction literature.[41]

He was a recipient of the Order of Merit (Knight of the Grand Cross) from the government in 1959.[42]

Books (selection)

[edit]- Pesci rossi. Firenze. 1920 – via Vallecchi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - La giornata delle belle donne (1924)

- L'osteria del cattivo tempo (1927)

- Trecentisti senesi (1928)

- Qualche cosa (1931)

- Messico (1932)

- Et in Arcadia ego (1936)

- Corse al trotto. Saggi, capricci e fantasie (1936)

- America amara (1939)

- La scultura fiorentina del Quattrocento (1956)

Filmography (selection)

[edit]- The Table of the Poor (as screenwriter: 1932)

- Steel (as producer: 1933)

- Ragazzo (as screenwriter: 1934)

- 1860 (as screenwriter and producer: 1934)

- Piccolo mondo antico (as co-screenwriter: 1942)

- Tragic Night (as screenwriter: 1942)

- Yes, Madam (as co-screenwriter: 1942)

- Giacomo the Idealist (as co-screenwriter: 1943)

- Harlem (as co-screenwriter: 1943)

- Under the Sun of Rome (as co-screenwriter: 1948)

- Escape to France (as co-screenwriter: 1948)

References

[edit]- ^ "Cécchi, Emilio". Biografie in Letteratura. Treccani. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Cecchi, Emilio". Enciclopedia del Cinema. Treccani. 2003. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Felice Del Beccaro [in Italian] (1979). "Cecchi, Emilio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Frederico Luisetti (section author); Gaetana Marrone (compiler-editor); Paolo Puppa (compiler-editor) (26 December 2006). "Emilio Cecchi (1884 - 1966)". Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies. Routledge. pp. 430–432. ISBN 978-1-135-45530-9.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ Nicoli p.122

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pasquale Maffeo (31 August 2016). "Anniversari. Cecchi, quel critico fedele". Avvenire Nuova Editoriale Italiana S.p.A.- Socio unico, Milano e Roma. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Giuliana Scudder. Dai "notes" di Emilio Cecchi .... Curriculum. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 13–18. GGKEY:708PECU056N.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle; Joseph Archer Crowe. Storia Della Pittura In Italia Dal Secolo Ii Al Secolo Xvi. Le Monnier. ISBN 978-1-279-79243-8.

- ^ a b c Giuliana Scudder. Bibliografia di Emilio Cecchi. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 19–258. GGKEY:708PECU056N.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Enrico Riccardo Orlando (2017). "Emilio Cecchi: i "Tarli" (1921-1923)" (PDF). Università Ca' Foscari Venezia. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Graziella Pulce (1991). "De Robertis, Giuseppe". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Leonetta Pieraccini Cecchi". Testo da: Invisible Women: Forgotten Artists of Florence, di Jane Fortune. Advancing Women Artists. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b Orio Caldiron; Matilde Hochkofler (1988). Scrivere il cinema: Suso Cecchi d'Amico. EDIZIONI DEDALO. ISBN 978-88-220-4529-4. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b Masolino d'Amico (12 September 2016). "Mio nonno Emilio Cecchi artigiano fiorentino della parola". Cinquant'anni fa moriva un protagonista della cultura italiana. Anglista raffinato e critico letterario dalla prosa impeccabile. La Stampa, Torino. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Annalina Grasso (14 February 2014). "Emilio Cecchi: l'assolutezza dell'arte". '900 Letterario. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Meir Michaelis (1998). "Mussolini's unofficial mouthpiece: Telesio Interlandi: Il Tevere and the evolution of Mussolini's anti-Semitism". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 3 (3): 217–240. doi:10.1080/13545719808454979.

- ^ Letter from Emilio Cecchi to Giovanni Boine. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. 22 May 1915. p. 156. GGKEY:54N9NQTSZJ0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Federico Casari (2015). "The Elzeviro vindicated. Towards Emilio Cecchi's Pesci rossi" (PDF). The Origin of the Elzeviro. Journalism and Literature in Italy, 1870-1920. Durham University. pp. 145–171. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Carla Gubert. "Ipotesi per una fonte di Massimo Bontempelli" (PDF). In «Otto/Novecento», a.XXIV, n.3, settembre/dicembre 2000, pp. 55-74. Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia, Università degli Studi di Trento. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Paolo Leoncini (moderator); Federico Casari, Mariachiara Leteo & Emanuele Trevi (contributors) (15 November 2018). "Emilio Cecchi in London". Announcement of a Presentation with a synopsis covering Cecchi's six months in London during 1918/19. L'Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Londra. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ D. Mondrone (1973). La Ronda a l'impegno (book review). pp. 192–193. UOM:39015085064445.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Simona Storchi (August 2001). "Towards the definition of a modern Classicità: The forms of order" (PDF). Notions of tradition and modernity in Italian critical debates of the 1920s. University College London. pp. 60–114. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Cécchi, Emìlio". De Agostini Editore S.P.A. ("sapere.it"), Novara. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Felicia Bruscino (commentary) (1 May 1925). "Il Popolo del 1925 col manifesto antifascista: ritrovata l'unica copia". Commentary placed online 25 November 2017 after the discovery of a copy after it had been thought that all copies had been long since destroyed. Il Popolo, Roma. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Giovanni Sale (2007). La crisi Matteotti. Editoriale Jaca Book. pp. 144–156. ISBN 978-88-16-40726-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ A. Spinosa: Mussolini. Il fascino di un dittatore, Mondadori, Milano, 1989, p. 153

- ^ Gaetana Marrone (2007). "Robert Lonhi". Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies: A-J. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1074–1075. ISBN 978-1-57958-390-3.

- ^ "Occupants of and Symposia sponsored by the Chair of Italian Culture". Chair of Italian Culture at the University of California, Berkeley. Department of Italian Studies, College of Letters and Science, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Maria Matilde Benzoni (2012). Oltre il Rio Grande. In viaggio con Emilio Cecchi. FrancoAngeli. pp. 241–258. ISBN 978-88-204-0408-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Derek Duncan (author); Charles Burdett (co-editor) (2002). Giovanni Comisso's memories of the war. Berghahn Books. pp. 49–62. ISBN 978-1-57181-810-2.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ^ Fabio Amico; Ferruccio Canali; Lorenzo Giusti; Nicola Maggi, Susanna Pampaloni, Vittore Pizzone (2 January 2016). Arte e Critica in Italia nella prima metà del Novecento. Gangemi Editore spa. ISBN 978-88-492-9026-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Annick Duperray (1 January 2006). Looming and myths (1881-1942). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-8264-5880-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Marco Lucchetti (3 October 2012). Scienziati, filosofi e navigatori. Newton Compton Editori. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-88-541-4699-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Franco Serpa (2013). "d'Amico, Fedele". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Luca Caminati (chapter co-author); Mauro Sassi (chapter co-author); Frank Burke (compiler-editor) (10 April 2017). Notes on the History of Italian nonfiction film. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-00617-6.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ^ Don Shiach (28 May 2015). The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). Oldcastle Books. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-84344-750-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Torino Giornalismo: città ricorda Emilio Cecchi a 50 anni dalla morte". La Voce del Canavese. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Victoria G. Tillson (2010). A nearly invisible city: Rome in Alberto Moravia's 1950s fiction. Vol. 28. Annali d'Italianistica. pp. 237–256. JSTOR 24016396.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Fausta Samaritani (compiler-publisher) (14 January 2002). "Leo Longanesi: Scrittore, grafico, editore". Non siamo né artisti, né critici, né letterati: noi abbiamo solo dei rancori, delle antipatie, delle convinzioni, degli umori e cerchiamo di esprimerli come meglio ci è concesso. Critica della letteratura italiana. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Elena Gelsomini (10 May 2011). L'Italia allo specchio. L'Europeo di Arrigo Benedetti (1945-1954): L'Europeo di Arrigo Benedetti (1945-1954). FrancoAngeli. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-88-568-6539-4.

- ^ "PREMI "Antonio Feltrinelli" FINORA CONFERITI". Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Cavaliere di Gran Croce Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana". Emilio Cecchi, Giornalista Scrittore. Presidente della Repubblica, Palazzo del Quirinale. 2 June 1959. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Marina Nicoli. The Rise and Fall of the Italian Film Industry. Taylor & Francis, 2016.