Embassy of the United States, Budapest

| Embassy of the United States, Budapest | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Budapest, Hungary |

| Address | 12 Liberty Square, Fifth District |

| Opened | December 26, 1921 |

| Relocated | From 12 Imre Steindl Street (then: Árpád Street) to 12 Liberty Square |

| Ambassador | David Pressman (since the summer of 2022) |

| Jurisdiction | Hungary |

The Embassy of the United States, Budapest is the diplomatic representation of the United States in Hungary, located in Budapest in the Fifth District, at 12 Liberty Square. The embassy is housed in the building of the Hungarian Commercial Hall, which was inaugurated in 1901. Since the summer of 2022, the embassy has been led by ambassador David Pressman.[1][2][3]

History

[edit]Hungary–United States relations on a diplomatic level began during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The first American embassy was actually opened in Vienna, and the first American envoy presented his credentials on November 7, 1838.[4] Diplomatic relations were severed during World War I, and the peace treaty between the two countries was signed on August 29, 1921.[5] Only after that could discussions about opening separate diplomatic representations for Hungary and the USA commence. Even before this, the USA was not without representation in Hungary. On December 4, 1919, Ulysses Grant-Smith arrived in Hungary to represent the American government.[6] Grant-Smith opened an office at 12 Lendvay Street, and his assignment was confirmed on January 27, 1920.[7] The embassy was officially founded on December 26, 1921, with Ulysses Grant-Smith serving as the chargé d'affaires. He was succeeded by Theodore Brentano, who represented the United States from May 16, 1922, with the title of Minister Plenipotentiary.[6]

The embassy and consulate moved to 12 Imre Steindl Street (then: Árpád Street) in 1930.[8] In 1933, negotiations began with the Hungarian Post Savings Bank for the lease of the nearby location at 12 Liberty Square.[9] The embassy opened at this now-famous location on January 20, 1934, initially leasing the offices but eventually displacing all previous tenants. Budapest's fifth post office operated in the building from 1933 until 1947, when the Americans transitioned from tenants to owners.[10]

On December 13, 1941 Hungary declared war on the United States.[11] However, United States Congress did not approve the state of war, and thus the embassy continued to operate. Envoy Herbert Pell left Hungary on January 16, 1942.[6] The embassy building was temporarily entrusted to the Swiss, and was occupied by Consul Carl Lutz, who directed his humanitarian activities from there.

Following World War II, an American diplomat, Arthur Schoenfeld, arrived in Hungary in January 1945 as a representative of the Allied Control Commission. He was appointed as envoy on December 15, 1945, and presented his credentials on January 26, 1946.[6] That same year, the Americans purchased the building on Liberty Square. During the Rákosi era, relations became increasingly strained, culminating in the expulsion of Ambassador Selden Chapin in 1949.[12]

During the autumn of 1956 a transition was occurring at the embassy. The new envoy, Edward T. Wailes, arrived in Budapest on November 2—two days ahead of Soviet tanks. Due to the unfolding events, he was unable to present his credentials, and ultimately didn't want to present them to the Revolutionary Workers'-Peasants' Government of Hungary. He was expelled in February 1957.[13] In 1956, József Mindszenty sought and was granted asylum at the embassy. He lived there for nearly one and a half decades, unable to leave the building for fear of arrest.

During the Cold War years the embassy existed but due to tense relations, no ambassadors, only temporary chargés d'affaires, were stationed in the other country. The USA did not have an appointed ambassador in Hungary between 1957 and 1967. The relationship was further complicated by Mindszenty's presence in the embassy and the USA's foreign policy at the time (Vietnam War). It was not until 1966 that relations began to improve.[14] Embassies were upgraded to ambassadorial status, and both countries finally sent ambassadors to lead their missions: the USA sent Martin J. Hillenbrand in 1967, and Hungary sent János Nagy in 1968.[15]

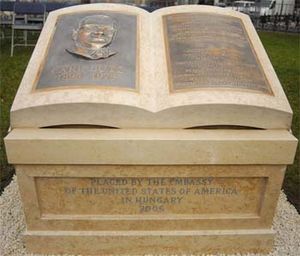

Carl Lutz Memorial

[edit]

Carl Lutz was the Swiss Vice-Consul in Budapest from 1942 until the end of World War II in 1945.[16] He worked out of the U.S. Legation building, which was located at 12 Liberty Square.[16][17]

Lutz's rescue efforts during the war are highly noted. He collaborated with other diplomats from neutral countries such as the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg, the Apostolic Nuncio Angelo Rotta, and the Italian Giorgio Perlasca.[16][17] By declaring buildings as annexes of the Swiss legation, Lutz extended diplomatic immunity to 72 buildings across Budapest.[16][17] As a result, more than 62,000 Hungarian Jews were saved from deportation to concentration camps.[16][18]

A statue commemorating Carl Lutz was unveiled on December 13, 2006, in a park adjacent to the U.S. Embassy at 12 Liberty Square.[17][16] The ceremony was attended by Hungarian, Swiss, and American politicians, as well as representatives of the Jewish community.[17][16] The memorial acknowledges Lutz's courageous actions that saved tens of thousands of Hungarian citizens persecuted as Jews during World War II.[16]

Statue of Harry Hill Bandholtz

[edit]

On the eastern side of Liberty Square park, next to the Hungarian National Bank, stands a statue commemorating Brigadier General Harry Hill Bandholtz. Bandholtz, an officer in the United States Army, played a significant role as part of the Inter-Allied Military Mission tasked with overseeing the withdrawal of Romanian troops from Hungary in 1919 following the Hungarian–Romanian War.[19]: p. xxii and xxviii

The inscription on the statue, a quote from Bandholtz, reads: "I simply carried out the instructions of my government, as I understood them, as an officer and a gentleman of the United States Army."[20]

The statue was unveiled in 1936, created by renowned Hungarian sculptor Miklós Ligeti. It portrays Bandholtz holding a riding crop behind his back, a compromise reached due to Romanian objections to the statue.[21] The riding crop signifies an incident on October 5, 1919, where Bandholtz stopped Romanian soldiers from entering the Hungarian National Museum and taking artifacts and treasures from within it.[22][23] According to the Romanian military authorities occupying Hungary, they wanted the returning of the Transylvanian heritage assets from the museum that retreating Austro-Hungarian troops had previously taken from the region at the end of World War I, some of which were willingly returned as Bandholtz himself confirmed.[23]

Originally supported by the Horthy government, the statue was temporarily removed for "restoration" by the Communist government in the late 1940s. In the late 1980s, it was re-installed in the garden of the ambassadorial residence in Zugliget at the request of Ambassador Nicolas M. Salgo. It was finally returned to its original location in Liberty Square in July 1989, ahead of a visit from U.S. President George H. W. Bush.

Every year, on the anniversary of Bandholtz's birth, the American military attaché lays a memorial wreath in front of the statue.

References

[edit]- ^ https://dailynewshungary.com/us-ambassador-visits-hungarian-president-with-his-rainbow-family/

- ^ https://444.hu/2022/11/15/az-amerikai-nagykovet-aggodik-amikor-moszkva-kijevet-raketazza-szijjarto-meg-kozben-a-gazprom-kozpontjaba-repul

- ^ https://www.politico.eu/article/victor-orban-enemy-david-pressman-united-states-ambassador-to-hungary-lgbtq/

- ^ [1] www.state.gov

- ^ "A M. kir. ministeriumnak 11.017/1921. M. E. számú rendelete". Külügyi Közlöny. 2 (1): 3. 1922-01-20.

- ^ a b c d "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Hungary". Department of State USA – Office of the historian. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- ^ "III. Egyéb diplomáciai képviseletek". Külügyi Közlöny. 1 (6): 70. 1921-10-19.

- ^ "A m.kir. belügyminiszternek ad, 141.541/1930. B.M. számú körrendelete". Belügyi Közlöny (36): 600. 1930-08-10.

- ^ "A Postatakarék szabadságtéri bérpalotájába költözik az amerikai követség". Pesti Napló. 84 (223): 26. 1933-10-01.

- ^ "Postaszervekben beállott változások". Posta és Távirda Rendeletek Tára (41): 298. 1947-08-16.

- ^ Szűcs László (2010-12-12). "Hadüzenet az Egyesült Államoknak". Honvédelem.hu. Archived from the original on 2019-07-15. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- ^ Béládi László (2000). "Magyarkronológia". Terror Háza. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25.

- ^ Kiss József; Ripp Zoltán; Vida István (1993). "Források a Nagy Imre-kormány külpolitikájának történetéhez". Társadalmi Szemle. 48 (5): 90-91.

- ^ Garadnai Zoltán (2001). "A magyar-francia diplomáciai kapcsolatok története, 1945–1966". Külpolitika. 7 (1–2): 120.

- ^ Baráth Magdolna; Gecsényi Lajos (2015). Főkonzulok, követek és nagykövetek. Budapest: MTA BTK Történettudományi Intézet. p. 228. Archived from the original on 2019-03-21. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Carl Lutz Memorial". Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Carl Lutz Memorial Unveiled in front of U.S. Embassy". Archived from the original on February 4, 2007.

- ^ "Ronald Reagan and Other Hungarian Heroes". The New Yorker. July 21, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ Bandholtz, Harry Hill (1966). An Undiplomatic Diary. AMS Press. pp. 80–86. ISBN 9780404004941.

- ^ "Statue of Harry Hill Bandholtz – Budapest, Hungary – Embassy of the United States". usembassy.gov.

- ^ "BpN. 4. 1994/2 – L. Nagy Zsuzsa: A főváros román megszállás alatt". Archived from the original on 2007-03-21. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ^ "3en-32.htm". Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ^ a b "Cum este folosită istoria pentru a se arunca cu noroi în România? [How is history used to drag Romania through the mud?]" (in Romanian). Adevărul. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.